Blog Archives

Criterion: Trafic, Jacques Tati, 1971

As workers and mechanics are preparing to send their model car off to Amsterdam for a car show, we hear them whistle a number of familiar tunes. We hear snippets from Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, Mon Oncle, and probably various others if you listen carefully. The trace of Hulot’s presence is immediately evident, even if we do not see him for a few minutes.

The shock of Hulot’s introduction in Traffic is that he is employed. Previously, he was nearly unemployable. In Mon Oncle, he bombed an interview and got fired from a job for incompetence, and in PlayTime, he could not even navigate the modern world to get time in the same room with a potential employer. Even in Jour de Fete, where Tati’s Francois could be seen as a prelude to Hulot, he has a job and is absolutely terrible at it.

In the years after PlayTime, Hulot has clearly had a change in ideals. Not only is he employed at an auto company, but he is an actual designer. The car that he ends up designing would be admired by the Arpels from Mon Oncle or by the invention expositioners in PlayTime. It is an entirely modern camper, a way of getting outdoors and enjoying life, but with a lot of clever, innovative and sometimes useless features that are the exact type of thing that baffled Hulot previously.

The fact that he obtained the job and designed something modern and silly is a mystery, but that’s not at the heart of the story. He and his team are responsible for transporting his model camper car to an auto show in Amsterdam. As can be expected, a lot of hijinks occur along the way that slow down and threaten to half the trip entirely.

In some ways Traffic is similar to the previous three films. They are mostly in long shot without close-ups, with sight gags that are easy to miss the first time through, not too much dialogue from the main characters, plenty of background noise, a mixture of languages, and of course, Monsieur Hulot is at the center of it all. Despite these similarities, this does not feel like the same type of Tati film. Perhaps it is unfair to compare it to the previous trio, which are arguable masterpieces, but everything seems a little more watered down this time out. The jokes are not quite as inventive. There are big laughs, such as when Hulot hangs upside down while trying to fix some ivy, but it feels like it has been done already. Previously Tati had been pushing his art a little further each time, and that resulted in PlayTime, his finest film. Traffic feels like a creative step back.

That is not to say this is a bad movie. Lesser Tati is still enjoyable and worth watching, and there are plenty of quality scenes. The traffic accident scene ranks up with the best of Tati’s scenes across his entire filmography. There are other lighter touches, such as the windshield wipers reflecting the look and personality of the drivers, and the mass of umbrellas at the end, that are full of the Tatiesque charm. Yet, for all of those, there are other scenes that don’t quite work. I could have done without the anonymous nose-picking in cars, which is too easy and not nearly as intelligent as most of Tati’s humor. There is also the cruel practical joke that makes Maria mistake her dog for dead, when the doppelganger is a mop with a button nose and far from realistic. Tati was probably trying to connect the children’s pranks from Mon Oncle, but those were organic and fun, whereas the dog prank is tired and transparent.

The ending is up to par with the rest of his work. When Maria is on the boat in the water, we see her appreciate the beauty of her surroundings, which is consistent with Tati’s typical arc of anti-technology and humanizing his characters. When they get away from the hustle and bustle, they find themselves refreshed and their personality changes for the better. Like with PlayTime, they go in circles rather than squares, only in Traffic they embrace quiet and solitude as opposed to the everlasting automobile congestion.

The end is bittersweet. Even though this film is not quite up to par with the remainder of Tati’s work, it is the final film for an endearing character. The outcome for Hulot is no surprise, but we’d like to know what awaits him next. We’ll miss him. It is not easy to say goodbye to Monsieur Hulot. Adieu, my friend!

Film Rating: 6.5

Supplements:

“Jacques Tati in Monsieur Hulot’s Work” – This is a 1976 program from the British show Omnibus. It begins at the beach house of Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday. Most of the special consists of interviews with Tati about his craft and his films, jumping backward and forward throughout his work. The one thing I have learned from this set is that Tati is not the greatest interview, which is perhaps because of the language barrier, but more likely because he is protective, defensive and not too revealing about his art. Nevertheless, he does say some interesting things about his work. Tati says he is not criticizing modernity, but is defending people who feel they have to change. This makes sense with Traffic because Hulot tried to assimilate into this new, high-tech society, only to fall on his face yet again. My favorite part of this special was his comparing himself with the old masters, specifically Chaplin. His comedy is passive rather than Chaplin’s active. He talks about the wreath and tire part from Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, and how differently Chaplin would have orchestrated the gag.

People ask him why he made so few films over the years, but he liked to do them in his own way with creative freedom, without making something that doesn’t live up to his style. He adds that “in life, you only have so many ideas.”

With only one major supplement and a film that doesn’t measure up to Tati’s filmography, this disc is the most disappointing, yet still worth a watch.

Criterion Rating: 5/10

Criterion: It Happened One Night, Frank Capra, 1934

In the interest of full disclosure, I’ll come clean that I’m not a Capra fanatic. That’s not to say that I don’t have tremendous respectful for him as a talented and influential filmmaker, and I like most of his films, even if I do not love them. My first exposure to him came during my younger cineaste years, when I was being reared on the edgy indies of the 90s and the new auteurs of the 00s. Compared to Todd Haynes or Tarantino, the “Capraesque” pictures of the classic Hollywood era seemed rather plain and mundane. Again, I thought they were good pictures, but they laid everything on a little too thick. There was too much ideology in Mr. Smith Goes to Hollywood, too much populism in Meet John Doe, and too much sentimentality in It’s a Wonderful Life.

When I first saw It Happened One Night, I had an anti-Capra bias. Just like with those other films, I did not hate his breakthrough comedy, but I did not love it either. I was ambivalent. That was easily 15 and possibly 20 years ago. I gave it another shot earlier this year, and came out with a newfound appreciation, yet still was not completely enamored. This Criterion disc gives me another chance for a re-visitation, and like their best releases, a new contextualization. Having a lot more knowledge about film history doesn’t hurt either. On this third viewing, the film grew on me quite a bit more.

First, in the context of his library, this film is not as “Capraesque” as I had originally remembered. Beginning with Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, his signature style really started to take shape, and was cemented as he continued to work. This film is actually unlike a lot of Capra’s later work, in that it’s more spontaneous, faster paced, and has a lot more of an edge.

It’s worth pointing out that this is a pre-code film. That said, it is a relatively benign pre-code film. The code would begin just a few months later. The writing may have been on the wall, but Capra did not indulge too much. When he did, it served the plot, such as the hilarious mannerisms of speech of Mr. Shapeley. At it’s core, the film is about sex, yet Capra danced around the subject in ways that undoubtedly inspired post-code filmmakers. The ‘Walls of Jericho’ way of dividing the hotel room is the perfect way to have a man and woman sleep together in a non-threatening way. It also became a suitable metaphor for the unspoken subject throughout the film. Some of the dialogue, the undressing scene, and the payoff of the ‘Walls of Jericho’ metaphor would probably have been altered in a post-code world, but it was indirect enough that it could have been a workable canvas to present sex in film.

There are three elements that make this simply a fun movie: Clark Gable, Mr. Shapeley, and “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze.” Gable was a delight, and played opposite the stone-faced Colbert with precision. The confident, charming and funny way he delivered his lines during their banter really sold the hostile courtship. He interacted with other characters in the same way, such as his boss, the detectives that try to search his hotel, and last but not least, Mr. Shapely. One of the funniest scenes of the movie, in my opinion, was the way in which Gable manipulates the misogynist character of Shapeley. Even though the character was funny, he deserved comeuppance, and the manner in which he was dispatched was one of the comedic high points. The song they sing on the bus does very little for the plot. It is more of a diversion than anything, but it conveys the relaxed, jovial atmosphere, where the courtship and the ‘One Night’ would eventually take place.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements:

Frank Capra, Jr. Remembers – Frank, Sr’s son remembers and discusses a lot of the details about the film. Of course he was born in 1934, so he did not remember anything firsthand, but he probably was exposed to a lot more about the film as a Capra than most others involved. He talked about the situation with Claudette Colbert, how she was about to leave for vacation and would only take the project if they doubled her pay and finished in four weeks. They agreed and literally had to begin production the next day. She was complaining all the time, and told friends that “I’ve just finished the worst picture of my life.” He says that Capra and Gable had a lot of fun making the picture. It shows.

Screwball Comedy? – Conversation between critics Molly Haskell and Phillip Lopate. It Happened One Night is sometimes called first screwball, but that is not altogether accurate. It is only loosely a screwball in the first place, at least in the way that future films would be considered. It was not as fast talking as Howard Hawks’ films, including Twentieth Century that came out that same year. The conversation moves on from looking at it from a screwball perspective and becomes a straightforward critical analysis, although they would often return to view the themes from a screwball point of view.

Fultah Fisher’s Boarding House, 1921 – This is the first Capra film. While his amateurism is on display, some of his skill is also clear. It works well visually, and he blends the title cards into the action effectively. The action scenes were effective, but the title cards were excessive and made the short film tough to follow.

Frank Capra’s American Dream, 1997 – This feature length documentary about Capra’s life was a treat. This and many of the other supplements make the disc far more than just the film. This is a tribute to the entire legacy of the filmmaker. Ron Howard narrates as they follow his origins as a child immigrant, the hard work that gave him opportunities in life, and of course his career in Hollywood. What was surprising was that after the huge success of It Happened One Night, Capra fell into a deep depression due to his success and guilt towards those suffering in the depression. This is where his career took a turn and he worked towards making films that the common man could appreciate. While this is often a criticism of the “Capraesque” method of filmmaking, it is also a justification for it. People in the depression were suffering. Movies were a low-cost escape for them. Capra gave them hope and inspiration, and considering the time, it does not matter how realistic his worlds were. Through this journey, I gained respect and appreciation for the man and his methods, even if I do not always adore his movies.

AFI Salute to Frank Capra – This was the 10th life achievement award in 1982. It plays as an hour-long awards ceremony. Jimmy Stewart hosts the show, beginning with a short feature about Capra’s childhood story up to his breakout in silent pictures. Many other celebrities speak, including Bette Davis and Peter Falk, who worked with him in Pocketful of Miracles. Claudette Colbert came out and was respectful, which is ironic since she had such a miserable time on the picture. Lionel Stander, from Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, said a few words, as did many stars who were influenced by Capra. These included Bob Hope, Jack Lemmon, Burgess Meredith, Fred MacMurray, Steve Martin, many more. It ended with Capra giving his acceptance speech, and truly enjoying the moment.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Criterion: Playtime, Jacques Tati, 1967

One of the recurrent statements found in the PlayTime supplements is that you have to see it more than once to truly appreciate. Due to the continual long shots, the wide frame, and the crowded amount of characters, there are many gags or comic touches in the background that will be missed. I first saw PlayTime years ago, as my first exposure to Tati, and I fell in love with it right away. This marked my third viewing, and as expected, I found plenty that I had missed during previous viewings, and I adored the film even more.

PlayTime is the culmination of Tati’s artistic and comedic exploits over the previous twenty years, which shockingly only resulted in three feature films. In this time he developed his ‘silent yet noisy’ comedy film, inspired by the giants of silent film, all the while making artistic statements about the modernization of society after the war. While PlayTime is just as hilarious as Mon Oncle or Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, it is grander on every level. It has more comedy, a more direct and pointed message, and is a more ambitious and impressive production.

Tati poured everything into this project, his time, fortune, property, and his credit, leaving him in shambles. Although it is a shame that the film ultimately was a failure and he suffered devestating consequences as a result, at least we were able to see on the screen exactly the type of film that he aspired to make. He even said that he had no regrets because of the final product.

The targets in PlayTime can be isolated and listed as modern architecture, tourism, invention, privacy, taste, or many, many others, but that takes away from the primary message he is trying to convey. Like much of his work, it returns to tradition versus modernity, just like the dogs that contrast with the humans in Mon Oncle, the revelry and lack of boundaries that the partiers experience when they finally get to ‘play’ is the message of PlayTime. Why be so serious and distracted by the trappings of modern society? It does not matter whether you can buy a pair of glasses that allows someone to apply makeup without taking them off, or buildings made of glass so clear that one cannot distinguish what is inside or outside. They are all ludicrous, tasteless, and take away from the essence of humanity, which I think Tati is able to illuminate at the end film.

The first half of film shows various characters, including American tourists, Monsieur Hulot, businessmen, and others frequenting a number of sleek and modernized locations. There are some instances where true French landmarks, such as the Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triomphe and Sacre Couer are reflected from opening doors, but those momentary images are all that we see of the beauty of Paris. Instead, most of the people spend their time at an expo with ridiculous inventions, most of which are impractical and some worthless (like a broom with lights or a silent door). We know that the tourists see some of France, because buses take them to Montmarte or Montparnasse, and they return with baubles and mementos, but they always return to these lifeless and nondescript buildings.

The latter half of the film takes place almost entirely in a restaurant and nightclub called the Royal Garden. It has been undergoing construction until literally the very last minute before customers arrive, and we soon find out that the restaurant is not quite ready to function. That does not stop people from flooding in. For awhile a doorman does what he can to keep the riffraff out, until Hulot destroys the glass door, allowing everyone entrance. Some are humorously guided there by the light fixture at the entrance, that turns them in a circle and points them into the restaurant. The restaurant is an absolute disaster until, yet again, Hulot’s clumsiness does more destruction. This time he destroys the framework of the architecture, and in it’s wake, leaves a more traditional looking bistro. This is where PlayTime begins, where he encounters a number of different characters, some of whom are locals and others tourists, but it does not matter. They all have quite a time by breaking the rules set forward by modernity.

What Tati is saying really comes into form through the last few images. He takes a liking to one of the American tourists, Barbara, and gets her a parting gift that she opens on the bus ride to the airport. It is a flower arrangement that resembles the street lights that enlighten the trip to Orly, reminding us that beauty can be found in the most unsuspected and curious places, but it is not some type of artificiality and disconnection to be manufactured, packaged and sold. As the cars continue towards the airport and day turns to night, the beautiful imagine remains in the unlikeliest of places.

Film Rating: 10/10

Supplements:

Terry Jones Introduction: He first saw it on a 70 mm screen, which I can only dream of. He could see all the detail in the long shots, and understood why there were not many close-ups. It was the most expensive French film of all time, a failure, but a ‘tour de force’ of filmmaking. Jones calls it the “most ambitious expression of Tati’s genius.”

Selected Scene Commentaries:

There are three commentaries. Historian Philip Kemp looks at roughly 45 minutes of footage and points out how the plot structure is that a number of straight lines in the beginning of the movie become curves towards the end. The statement is abstract, but he is able to demonstrate it by the on-screen behavior.

He talks about how PlayTime was a failure and bankrupted Tati and his family. He goes into the details of how Tati and the family put up so much of their own property and inheritance to finance the film, but it was a financial disaster and wasn’t screened in USA until much later.

Stephane Goudet looks at the beginning scenes in the office and expo, and then the later scenes with the “shopwindow” apartments. Even though the office setting appears intent on creating a more organized and efficient environment, it does the opposite. The spatial proximity of the cubes provides distance and disconnection. The apartments show no boundary between private and public life, and resemble the class conceit previous exhibited by the Arpels. It is no surprise that this scene was originally written for Mon Oncle.

Jerome Deschamps, a Theater Director, looks at the early scenes in the office. One scene in particular, which happens to be one of my favorites, is Mr. Giffard’s long walk down the corridor, coming from the background while Hulot and the secretary wait on the left in the foreground. They can hear his footsteps, but cannot see the long walk like the audience can. The scene takes a long time to unveil, but is worth it. Deschamps then looks at the scene in the waiting room, where Hulot encounters and is fascinated by Mr. Lacs, and then misses Giffard because he is staring out of the window.

“Tativille” – This is an interview on the set of playtime from 1967 British TV. It was built on a hilltop outside of Paris. Tati escorts us through the set, which is barren and deserted, even more so than in the film. It shows how he choreographs actors, especially during restaurant scene. They are all amateurs and Tati orchestrates their actions a person at a time. The crew talks to the American wives from the nearby base, who really have no idea what type of film they are in, but they are enjoying the experience all the same.

“Beyond Playtime” – This is a short 2002 documentary from Goudet. There are more tours through Tativille, with background about the process. It took two years of filming, where a gigantic set was built from scratch, and it cost 15 million euros. Sadly, the set was later destroyed. Tati affectionately says “Playtime will always be my last film.”

“Like Home” – 2013 Visual essay from Goudet.

Talks about the criticism that Playtime has a lack of structure, but gives the same ‘straight lines turn to curves’ argument. He goes through many of the themes and points out gags that are easy to miss. Finally, he talks about how the film ends with a sense of poetry. Tati said that “I want the movie to begin when you leave the theater.”

Sylvette Baudrot – Interview about the behind-the-scenes process with Baudrot, She talks about a gag that they were not able to pull off, which was an attempt to make the streetlights appear to be watering pots that are hydrating the tourists in the buses as they pass. Instead that premise is used in the restaurant where it appears the waiter pours Champagne onto the ladies hats. She talks about how Tati was an ultra perfectionist with timing, color, and just about everything else. They used cutouts of the Paris buildings that we would see through the windows, as well as cutouts of people as extras and side columns on the building. These were expensive, but in some cases it was cheaper than the alternative, like hiring 100 more extras. One terrific touch that she shared was how funny Tati could be when he acted out the parts to the actors, which included the ladies. Because of his early career as a mime and experience as an actor, he was able to show them virtually everything.

Criterion Rating – 10/10

Criterion: Ride in the Whirlwind, Monte Hellman, 1966

While Ride in the Whirlwind sbould be compared with the film that preceded it, The Shooting, it is not a carbon copy. It shares many elements in common with the companion film. The most obvious is the cast members of Jack Nicholson and Millie Perkins, but there were also many of the same locations, the same crew, and even the same horses.

Despite these similarities, the differences are more distinctive. First and foremost, the style is different. If these two pictures are considered “acid” westerns, then The Shooting is far more “acidic.” Whirlwind is actually quite linear in comparison. Rather than being oblique with major plot elements left to the viewer’s imagination, this time the narrative is clear and direct. There are four different groups of characters with conflicting motivations, and we get the general idea of what they are about. The first group are outlaws; another is a group of cattle-hands trying to pass through; the third group are the vigilantes, and the final group is a farming family in the wilderness.

The premise is that the cattle-hand protagonists end up in the wrong place at the wrong time. They encounter the outlaws, who unsuccessfully try to pass themselves off as cattle-hands. After an awkward meeting between the two groups, they camp out and find themselves under fire from the vigilantes before they can depart. They are completely innocent, but in the eyes of those with the guns, they are guilty by association.

Only two of the three cattle-hands survive the initial shootout, played by Cameron Mitchell and Jack Nicholson, and they make it out of the camp on the same horse. From here begins the existential dilemma on who is and isn’t an outlaw. Who is good and who is moral?

After escaping out of the valley, they encounter the farming family. They assure them that they are good people, not outlaws, but they have to do certain things in order to escape from their accusers. One thing they need to do is take the farmer’s horse, which is theft. They try to justify it because otherwise they will hang for something they didn’t do, but theft is theft. In the farmer’s eyes, they are taking his horses and that is unjust. They are intruding on the family, eating their food, making them uncomfortable and putting them in harm’s way. As the story unfolds, the ‘innocents’ commit other acts that blur the lines further. Every man that turns towards the immoral has to follow a series of actions. While we side with the main characters that we believe are good people, it is perfectly justifiable that they would be seen as evil under the circumstances.

Nicholson and Perkins play completely different characters than in the previous film. Nicholson’s character is unlike most of what he would play in his later, illustrious career. He is softer spoken, kinder and gentler. He tries to endear himself towards Perkins, whereas most outlaws would not care one bit. He plays the character well, but in an understated, muted fashion. There is no chewing scenery here.

Perkins played a sort of Femme Fatale in The Shooting, but here she plays a meek, naïve and inexperienced young farm girl. She is not nearly as savvy or manipulative. In the special features, Perkins says she tried to play the girl as if she was imitating one of her chickens. That makes sense, as the girl is physically and socially awkward, and does not know how to behave around people outside her family.

It is clear that even when the duo has the family hostage, that Hellman wants us to like them. They remain kind and respectful, and plead that they are not evil people. They even play checkers to pass the time. They can be as nice as they want, but the existential crisis remains. They are in control of the situation, holding people against their will and forcing them to keep their presence quiet. The circumstances of how they ended up in that situation are immaterial. There are there, and in the eyes of the victims, they are just as criminal as the stage robbers.

Even though both of these films were shot inexpensively, they get the most out of the small budget. Visually, both films look far better than other independents from the era, even if The Shooting has more showy shots. Whirlwind is more straightforward, mostly because that is what the plot calls for. There are more characters and more events to unfold, which require shorter shots with more cuts. There are a few exceptions where the camera is allowed to breathe, such as the visually striking scene when the pair are climbing to get out of the valley. Another impressive shot is the final scene. It may be the prototypical cliché shot of a character riding off into the sunset, but it adds some panache. Rather than just watching him ride off, he is enveloped into the misty clouds, or the whirlwind as the title implies. It looks good visually, but it also fits the film thematically. The world has changed for this character, and we know that even though he survives, it will not be a pleasant existence. He has come full circle and is what he hated.

Film Rating: 6.5/10

Supplements:

Commentary: Again, we had the same participants from The Shooting and they had a similar dynamic. The film historians would comment based on their own knowledge and experience, while peppering Hellman with questions about the production and background.

One interesting aspect of this commentary was the level of Nicholson’s involvement. He was not the star that we know today, and he wrote and acted in the film. We don’t think of him as a writer, and it says something that the character he wrote for himself was so far from the type he would play throughout his career. For the screenplay, Nicholson researched stakeouts at the library, and this particular story was based on a real shootout that took place over three days.

It was impressive hearing Hellman discuss how the cabin burning took place. It looks spectacular on the screen, yet they had to contain the fires so they could continue shooting without destroying the set. Had to show multiple stages of the fire, and of course, it ended with the set destroyed. It was risky to try to pull off with the limited budget, but it worked amazingly well on screen.

This was a productive year for Hellman. He had made two Philippines movies prior to this, so with these two westerns, he had made 4 movies in 12 months. That is a third of his career output in one year, which is saying something.

House of Corman – This was a conversation between Roger Corman and Monte Hellman. It’s a very chummy talk. One thing that they do not bring up, that Hellman revealed in the commentary, was that Corman did not want to make the films once he saw the screenplays. He didn’t think they could be commercially successful. Instead they talk about Corman’s decision to make two westerns, and his influence on American filmmakers by that time. His influence was considerable, and Hellman was one of his protégés that would not have the same career otherwise.

The Diary of Millie Perkins – In The Shooting, she put dirt on her face to cover discrete makeup. She wanted some sort of unique look, so the mud became her makeup. She talked about her horseback riding, which she handled quite well, a lot better than the other actors. She had an interesting relationship with Jack during the time, and they are still friends. They bonded.

Whips and Jingles – This is a Will Hutchins interview. He talks about running up hill with chalk. He was in decent shape, but not an easy run and had to call a medic. One thing that comes up often in all these features is Jack and Monte arguing about budget, but they had to pay out of their pockets if they ran over. He accidentally stumbled into a Parisian theater in 1969 and was surprised to see The Shooting and RTW playing. He had no idea it had been released anywhere.

Blind Harry – This was a short discussion between Hellman and Harry Dean Stanton. Jack said don’t do anything, play yourself, just act. That’s interesting because he’s been accused of doing that on a couple occasions. Harry was head of the gang so he didn’t have to do anything. This was a major influence on his future approach to acting.

The True Death of Leland Drum – Hellman talks to B.J. Merholz and John Hackett, actors in Ride in the Whirlwind. They were amateurs, which Hellman makes the point is not a dirty word. They talk about the horse wrangling, which is a recurring theme in all of these supplements because a high percentage of the budget went towards horse wrangling due to the teamsters union.

Heart of Lightness – Hellman speaks with Assistant Director Gary Kurtz. They talk about all the rain early in The Shooting that caused production delays. The crew was small, with one or two in the art department, one horse wrangler, two cameramen, two sound men, and one on wardrobe. Again, it is quite a final product for such a slim production.

The Last Cowboy – They talk to Calvin Johnson, the horse ranger that worked on the films. He had worked on westerns since he was 10 years old. They revisit the locations. Pahreah was one of the towns where they shot, which is long gone now. Talks about shooting at the “staircase” near Bryce Canyon where they had the final scene in The Shooting. The locations were just gorgeous.

An American Legend – This was my favorite supplement on the disc. It is a critical piece by Kim Morgan on the career of Warren Oates. Much of it is a career retrospective, but she also discusses the “it” factor that made him such a renowned actor. She says it starts with the face. He was a type of “gorgeous ugly,” as she puts it, recounting his attractive, grizzled look. The Shooting was his first leading role, which began a Hellman collaboration over a few films. He was thought of as a character actor, which is unfair, probably because his lead films were in smaller, grittier films from Hellman and Peckinpah. He died too young. Who knows what the future auteurs of the 90s and 00s could have done with him?

Even though there are far better movies in the Collection, this disc is loaded with two quality films and a ton of features. One of the notable absences on the features is anything from Jack, although he has been in retirement lately and may not have been up for it.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Criterion: The Shooting, Monte Hellman, 1966

The Shooting and Ride In the Whirlwind were companion, low budget westerns pieces, shot together over a 7-week schedule (3 weeks for each with a week off in between). At the time they were overlooked, but have become cult classics and influenced many of the ‘Acid Westerns’ that followed.

Of the two, I consider The Shooting to be superior. Maybe not so coincidentally, it also had the most problems with the production. Some flooding took place early and forced delays. While the movie was wrapped up in time and within the budget, there appear to be some short cuts taken. Some scenes probably did not get the coverage they deserved, and there are gaps in editing. Towards the end, the narrative skips and jumps ahead without dissolves, making the passage of time less clear and challenging the viewer

For such a small budget, the film looks spectacular. Some of the beginning photography has a gritty, washed out look, which may have more to do with the production delays than anything. The later scenes in the desert are brighter and more photogenic, in part because of some great choices in locations. Aside from a handful of interior shots, most of the movie was lit with natural light on location. DP Gregory Sandor deserves credit for making the most with limited resources, as the film does not look cheap by any stretch on the screen.

Compared to Ride In the Whirlwind and other westerns that came before and would come later, The Shooting is minimalist, with sparse dialogue and a lot of long shots of the characters that highlight the locations.

Warren Oates, who would become familiar to most film buffs later, was starring in his first lead role. Willett Gashade was a fitting character for him. He is quite, sober, sensible, and stoic, which is in stark contrast to Will Hutchins’ Coley Boyard, who is boisterous, cowardly, and wears his emotions on his sleeve, particularly his fondness for the mysterious woman that would set the narrative in motion.

Millie Perkins plays the unknown woman. We never learn her name, despite Coley’s attempts to learn it and get closer to her. She is also uniquely portrayed. In previous westerns, the villain’s are almost universally male. She is more like the mysterious femme fatales in noir films of the 1940s and 1950s. While we learn early on that she is on a mission of revenge, she keeps quiet as to her motivation until the very end, and we never learn of the circumstances that brought her there.

It is impossible to review Jack Nicholson’s involvement outside of the context of his later performances. While The Shooting was created before he was known, this is the same, familiar Jack that would rise to stardom in the upcoming decade. Like Perkins, he plays a reserved and quiet character and reveals next to nothing about why he does what he does. He reveals some information about a crime he has committed, but does so in the confidence of a character and the audience never understands how and why. His character relishes in cruelty, and he shows the same bright white, wicked smile that we would see later in his career. He grins widely and wickedly as he tells Coley, “Your brain is gonna fry out here. You know that?”. It is the same expression he would later use in The Shining, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and many other roles throughout his career. Even though he does not appear until the middle of the film with an unceremonious entrance, he steals most of his scenes.

The last 15 minutes are where the picture is the most impactful. They are when the action resolves, and they are also the most enigmatic and would embody the “acid” characteristics. There are some questionable editing decisions, such as when Gashade is burying a body. Most of the events unfold visually without narrative. We do not know how long they have been out there. The ending resolves the fate of some characters, but we do not know the fate of the rest. The actual ending is amazing, as ‘The End’ is written on the screening during a long shot with one of the remaining characters. Does that mean it is his end as well?

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements:

Since this is a single disc combined with Ride in the Whirlwind, I am going to discuss the supplements in the entry for the other film.

Commentary:

The audio commentary was recorded this year with Hellman, film critic Bill Krohn, and western historian Blake Lucas. The three have an interesting dynamic. At times I wanted to hear more from Hellman about the production of the film, but on the other hand, I enjoyed them interacting with him and asking film geek types of questions. Without them, we probably wouldn’t have learned as much about his influences going into the film.

With this project, he wanted to get to the major question, as Hellman put it. He actually eliminated 10 pages of exposition just to speed up the plot. He eliminated dissolves as well, which he attributed to the French New Wave and the lack of a budget. Dissolves are more expensive.

His influences were of course John Ford films, and he mentioned a few others. One curious influence was One Eyed Jacks with Brando. He also mentioned that he was influenced by Antonioni, the French New Wave, and other arthouse cinema directors. Perhaps the most interesting influence was the JFK assassination. This project began soon after those events, and he said they were an influence on the film. You can see remnants of the Zapruder film and the footage of Oswald getting shot in the final scene.

This was a transitional period in westerns, which the critics commented more about than Hellman. The John Fords and Anthony Manns were slowing down, while Peckinpah was yet to come. One detail that came up but was not delved into was that Hellman was under discussion to do Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. I can only wonder how that would have turned out under his hand rather than Peckinpah.

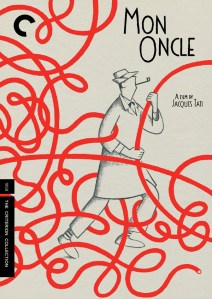

Criterion: Mon Oncle, Jacques Tati, 1958

Jacques Tati can be an absolute riot at times, and in my opinion, Mon Oncle is his funniest effort. While he does not relax his recurrent theme of tradition versus modernity, he has more fun with these characters, and the material is ripe for comedy with big laughs. Playtime also has some scenes with big laughs, but is a little quieter, slower paced, and takes the theme a little further. The latter is my favorite of the two, yet Mon Oncle is one I could see myself watching more frequently just because it’s a lighter and more pleasurable experience.

The fact that the movie is bookended by dogs running around randomly without a care in the world is no accident. The dogs are contrasted by the silly adults who spend the majority of their effort on appearances, trying to show off their nifty little gadgets and elaborate architecture. The Arpel family are pre-occupied with exemplifying their higher class, while the dogs care less – and that includes the house weiner dog. Even though he wears clothing that would only come from an upper class family, the dogs are seen as equals. They run together where they wish and do not discriminate, nor do they care about such symbols.

The behavior and attitude of the dogs are similar to that of the children. The young Gerard Arpel is dressed in a fine suit representative of his class, yet when he goes out to play with the lower class children that wear patchwork sweaters, he is treated as an equal. Like the dogs, they collectively gallivant around, have fun, and engage in whatever mischief they can find. This can be doing cruel things to others, like pushing on cars to make people think they were in an accident, or whistling from hidden locations and placing bets whether people will hit the signpost. Gerard cares nothing of the technology back at home. He would prefer to eat a cruller with jam and sugar rather than a technologically advanced boiled egg.

Gerard looks to his uncle, Monsieur Hulot, as a mentor and influence. Hulot is from an older, traditional France. Like with Villa Arpel, his home is a maze of sorts, but his is out of necessity and not intent. His is run down and he has to go through a variety of different paths in order to reach his loft apartment. The path to his door is not aesthetically crafted and manufactured like the Arpels. He has no fish fountain. Instead he finds that a bird sings when he opens the window enough to let the sunlight shine on it’s cage. This he does for his own amusement, and not to impress others.

Villa Arpel Reproduction

Villa Arpel is another matter entirely. Their house is the height of design. They have a winding S-shaped pathway to get to the front door. There is a small pond with a gigantic fish standing vertically with mouth in the air, which will erupt with blue water when the correct button is pressed. The courtyard has small square pads for walking, surrounded by gravel, grass, or some other brand of landscaping, requiring people to walk carefully if they venture off the main path. The house is modern even for today, with two large portholes that can appear as eyes in some scenes (which Tati uses for great comic effect!).

The house is ostentatious if not completely ridiculous. It is actually quite nice. What is ridiculous is the behavior of the Arpels that inhabit it. They are only concerned with what the neighbors think. The most obvious example of this is that they wait for the doorbell before turning on the fish fountain. If the visitor is a deliveryman or anyone else from a lower class, including Hulot, they immediately turn it off. It is not meant for the lower classes. If it is for a neighbor, co-worker, or any other guest, then the fountain continues to flow as long as the guest is present – or if the fountain breaks, which is another hilarious scene.

There are two worlds in this movie: The Arpel’s world and Hulot’s world. In one of the supplements, Francois Truffault is quoted as saying that one world is 20 years in the past, while the other is 20 years in the future. The old France is the traditional France. The colors of the town are muted and drab, mostly earth colors, with clutter and disarray everywhere. There is one notable pile of garbage that remains in the middle of the street for the entire film. There’s even someone who is sweeping (a reference to the postman in Jour de Fete), but he is doing his job as slowly and inefficiently as possible. The Arpels, on the other hand, are immaculate and obsessed with cleanliness. Mrs. Arpel goes so far as to wipe off her husband’s car to make it as shiny as possible as he is departing for work.

A lot can be said about the contrast between old world, pre-war values and the coming modernization and Americanization. It is no secret that the shiny cars that Arpel and others of his class drive are all American. Mr. Arpel drives a 1957 Chevy Bel Air. By contrast, those in the old France usually walk or ride bicycles. The plastic factory is another statement of modernization and industrialization, and the film mocks how they are merely making plastic hoses. Hulot is so out of touch with this world that he cannot even make a simple hose, and ends up making what looks like sausage links.

Did I mention this movie was funny? There are a few scenes that had me roaring with laughter. The Arpels’ dinner party scene was a riot, and I loved that one of the guests (one from a lower class) couldn’t help but laugh at the ridiculousness as it took place. Another funny scene was when they mistake a neighbor for a rug salesman, but she was just trying to impress them with flashy clothing.

After all of this poking fun of modernity and technology, the dogs are shown running around. The ending is perfect, and reminds us yet again that this artificial world, the high tech gadgets, and the attention means absolutely nothing in the big picture.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements:

Terry Jones Introduction. Jones was disappointed with the film at first, and then came around and it became his favorite Tati film. He thinks that the main titles speak to the primary theme just like anything else in the film with hand-created nameplates showing the production credits amid heavy industrial background.

My Uncle. This is the English-language version, which was filmed concurrently with the French version. There are English signs and dialog, which was dubbed in later. The background voices are still French, but that does not matter since the audio is unintelligible. The spoken language version does not make much of a difference because so much of the film is silent, at least not spoken, and the sound effects are all the same.

Once Upon a Time: My Uncle. This featurette talks about the production and puts it into historical context. There are many interviews, including some archived with Tati. Pierre Etaix speaks a great deal as his assistant. He talks about how well Tati choreographed each character’s movement down to the smallest detail.

“Lines, Signs and Designs.” This is a short feature about the architecture behind the house. They talk to different architects about the house, who give their opinions about the designs. Many of them agree that the design was a little much, but they do not overly criticize. Some of them get a little defensive. One architect says that Tati would have slammed his early work.

“Fashion.” This feature talks with a fashion designer about the outfits. She said the apparel was very 1950s. She singles out the rug lady that resulted in funny misunderstanding, all because she was trying to outdo Ms. Arpel. Back in the 1950s, there was a lot of attention to matching colors. One instance where this is seen in the film is with the dog’s vest matching Mr. Arpel’s scarf.

“Have a Seat.” Some designers reproduced the rocking chair, the “kidney” couch and the two cylinder couch. The latter is not very comfortable until people relax in it, and experiment with different ways to use it. This was not mentioned in the feature, but the entire house is reproduced here.

Everything’s Connected. Visual essay and critical analysis by Stephane Goudet. This is the most conventional plot of all his films.. Tati is not against modern archictecture, but the way people use it to show off. It is more of a class contrast. She compares it to other films, like in Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday where Hulot becomes a role model for the kids, but not what the parents probably want. That’s the case with the Arpels. He is more of a role model for Gerard and the child adopts Hulot’s values more than his parents.

With walking on the water lilys into the pool, Tati’s character enters water just like in his two previous films, but this time he is not submerged because the water is not deep enough. This provides continuity between the films and his world, but this instance of water is distinctly artificial whereas the others are real.

This was subtle and probably not noticeable to non-French speakers, but the name Hulot is mixed up with “hublot” on at least one occasion. “Hublot” means means porthole. There are many portholes in this movie, such as the holes in the garage, the holes upstairs as windows (or eyes), and the porthole in the interview scene.

“Le Hasard de Jacques Tati.” In this TV special, Tati talks about all the dogs in the film and his relationship with them, including Chance the mutt, his own dog. The dogs for the film were obtained from the pound, and afterward he put out an ad for people to adopt the “stars” of the film. He wishes he had 30-40 dogs because he could have found homes for all of them.

Criteron Rating: 9.5/10

Criterion: Down By Law, Jim Jarmusch, 1986

The Tom Waits lyric of it’s a “Sad and Beautiful World” originated a Roberto Benigni misunderstanding of the line, but it fit better and they chose to keep it. As it turns out, this line of dialogue encapsulates and can be thought of as a conclusion to the movie. The characters find sadness, misfortune, and beauty throughout their travels.

Down By Law is Jim Jarmusch’s third film, although he would argue that the first one, Permanent Vacation, didn’t count since he was young and had no idea what he was doing. His 1986 effort has a number of similarities with his second film, Strangers in Paradise, which turned out to be his breakthrough. A significant difference is that he had $100,000 to make that film, whereas he had over a million for the follow-up. He made the most out of his money for both movies, as they both look better than most similarly budgeted independent productions of the time. In fact, Down By Law looks far better than many more expensive films. Jarmusch was always good at making the most out of his limited resources, which was a skill that would continue throughout his career.

Like Stranger than Paradise, there are three central characters that become companions based on circumstance and whim. Two of the actors were talented musicians that were popular in independent/alternative music circles. John Lurie was a member of the Lounge Lizards, and Tom Waits was … well, he was Tom Waits – basically an icon of his genre. Both are good actors, and you can tell they have good chemistry together. One of the better scenes with the two was when they are both in a jail cell and Lurie’s Jack gets Wait’s Zack to demonstrate his DJ abilities. To Jack, who was a grimy pimp in New Orleans, being on the radio was another world, and he takes a liking to his cellmate.

Both men are innocent in a sense, victims of a vindictive setup by someone in their life. They had the intent to commit crimes, and Jack’s profession was a criminal. Zack was simply down on his luck and would do anything to make a buck. He encounters Roberto in an early scene, where he is playing music and lamenting being thrown out by his girlfriend. That’s when the “Sad and Beautiful World” song occurs.

Jack and Zack are not the ideal prison cellmates. While they initially find common ground and friendship, that devolves into animosity and anger. They get sick of each other quickly. They fight. Fortunately a new cellmate interrupts their bickering. Roberto is the same person who encountered Zack earlier, although neither of them men make that connection. Roberto is not innocent, but you could argue that he was justified in his crime and that it was self defense.

Roberto, played by the young, exuberant and affable Roberto Benigni that Hollywood would fall in love with 10 years later and then forget in 20 years. He basically plays himself here, an Italian immigrant who has very little command of the English language. Roberto is engaging and plays intermediary between his cellmates. Roberto, a stranger to the country, is the one who initiates action. Jack and Zack have little ambition. It is fitting for their characters that they would later pedal around in circles when Roberto, who cannot swim and is petrified of water, is helpless to guide them. Benigni continues to guide them, even catching food, which at first the quarrelling friends are too stubborn to eat. He is the one who takes the initiative to enter the only building they encounter, while the other two wait outside for something to happen. They are literally lost and out in the woods without him.

Down By Law is a more accomplished and mature film than Stranger than Paradise. It is clear that Jarmusch has learned a great deal in the intervening two years where he first achieved success. The beauty is thanks to the gorgeous Louisiana locations and the cinematography of Robby Müller. He had previously worked with Wim Wenders on his major works, including The Road Trilogy and Paris, TX. As we learn in the supplements, Jarmusch gave him the freedom and respect to shoot as he desired, and the end product was mesmerizing. There are many examples of some great shots, but the one that stuck with me was when the trio are running through a tunnel/sewer that’s light is textured by mirroring shadows of the shimmering water.

Because of the excellent photography, the performances (especially Roberto Benigni), Down By Law is among the best of Jarmusch’s work.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements:

Audio from Jim Jarmusch. It is unusual to have a lengthy speaking track on a Criterion disc that is not a commentary track. This supplement has Jarmusch discussing the film with only his picture on the screen. Perhaps he just doesn’t like audio commentaries, as he is a little picky with how his films are represented. At a 1:15 running time, this was a little much to get through.

Robby Muller Interview. He talks about his collaboration with Jarmusch. The only direction he got was that “it’s just a fairy tale” and he made Louisiana his canvas. He was allowed to follow his instincts. One surprising portion of the interview was that, of all the director’s he’s worked with, he has the most respect for Jarmusch. They had a long collaboration, but he has also worked with directors like Wenders, Von Trier, Friedkin, Winterbottom, and others.

Cannes Film Festival Press Conference. This was an interesting press conference because they revealed some details about the film, yet also it was something to see Jarmusch interact with the audience, some of whom asked terrible questions. He said so at times, and refused to answer. One of the most hilarious questions was near the end of the conference. Someone asked whether they felt the film was too long. They also asked whether they felt Paris, TX was too long. The questioner sais that while she enjoyed the film, she fell asleep during the early portion, partly because she had seen numerous films during Cannes. Jarmusch didn’t take the bait about whether his film was too long, and didn’t seem to take offense either. He shrugged it off. As for Paris, TX, he wouldn’t be so bold to re-imagine a work he respected. He said that if anything, he would make it longer, and snipped that “you would have fallen asleep earlier during my version.”

During the interview he sticks to his guns as a true independent spirit. He was not interested in big budget films, and has mostly stayed true to that in the years since (although Only Lovers Left Alive had a large budget). At the time he had already been offered larger budget projects, and had been offered larger budgets for his own projects, but he did not believe in having more money just to have it. He felt the cost should be dictated by the content of the movie.

While a lot of the attention was dedicated to Jarmusch, Roberto Benigni got his share. He was just as as hammy and energetic as we’d see during the Oscars for Life is Beautiful, although his command of the English language was not as strong.

John Lurie Interview. This was a short interview and Lurie looks tired, yet was frank and revealing about how it was on set, and what his career was like. He was offered lots of parts and turned them down, which was fortunate because a lot of them turned out to be bad movies. Like Jarmusch, he had an independent spirit and wanted to work on the right project, whether it was in film or music.

John Lurie Commentary on his interview. It was funny that he even did this. Years later, Lurie did a commentary track for this short interview. “Who is that guy?” he asked. He shows some self consciousness as he reflects on his younger self, and a little bit of embarrassment because he had been up all night when giving the interview and it showed.

Deleted scenes. The majority of these scenes were deleted for good reason. There were only a couple that really added much to anything. There was one where Zack is complaining about being innocent to a fellow prisoner in a nearby cell. The prisoner responds with laughter. “I’m fucking innocent!” he says, although obviously he isn’t. He is mocking Zack, who really was not innocent. He was just set-up.

There was another scene where Roberto is trying to coax Jack back from stewing after a fight with Zack. He had just cooked the rabbit and was using it to lure Jack back. “Buzz off!” Jack says, recalling the earlier scene where Zack says the same thing to Roberto.

It’s All Right With Me. This was a Tom Waits cover of a Cole Porter songs. Jarmusch directed the music video. It was a little more experimental than his cinematic work. It had jarring camera movements with Waits dancing in his own way.

Jarmusch Audio Q&A: This was more interesting than the audio conversation because the questions were better. It was the same format, with Jarmusch’s picture on screen as he talks. We finally learned to pronounce Jarmusch’s last name. Another answer was that Tom Waits was not drunk, which means he’s a good actor. They had some wild times while not filming. Jarmusch laid down the law and wouldn’t let drugs or drink on set, but didn’t try to control what happened off set. Influenced both by French New Wave (Godard, Rivette) and NY Punk scene, which he grew up in, and that shows. He talks about books and music that he’s into, and is very literate, very well read, and ensconced in independent pop culture of the day. This contributes to the quality and cynicism found in his films. He’s a punk, but a smart one.

Telephone conversations: This is more of a novelty, as Jarmusch calls the three leads and records their conversations. Roberto is shot out of a cannon, just like he always is. Hardly spoke English during the filming, but speaks well now. John Lurie and Jarmusch name dropped all the music they saw down there, most of which I’ve never heard of. Jarmusch cannot watch the movie, which may explain why he chose not to record a commentary.

This is a great film and stacked release with plenty extras. The only thing lacking is a commentary. I’m tempted to give this one a perfect score, but I cannot justify giving that to any release without a commentary.

Criterion Rating: 9.5/10

Criterion: Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday

MONSIEUR HULOT’S HOLIDAY, JACQUES TATI, 1953

Summer vacation is a time to get away, to adventure, relax, and get away from the hustle and bustle of daily life. Jacques Tati plays with this logic, as some of his characters make the most of their vacation, while others bring their city lives with them. At the center is the theatrical debut of Monsieur Hulot, who aligns with and is arguably the catalyst for people enjoying themselves during their time off.

From his first appearance as he is driving his meager, sputtering and backfiring, tine Samdon A3, Hulot is introduced as a different type of character. He’s odd, clumsy, sometimes uncomfortable in his own skin, and his unconventional behavior and tastes make him an outlier compared with the traditional vacationers. He barely speaks, and is the center of the comedic gags that take place. He is also the embodiment of the central theme of Tati’s film (and those to come) of tradition versus modernity. Hulot initially seems not to belong because he awkwardly interacts modern technology, but he ends up belonging in his own way.

Holiday is ultimately a comedy, and bears a strong resemblance to the silent comedies that inspired him. He does pack in quite a lot of big gags, the type of which would be familiar in a Buster Keaton or Harold Lloyd picture. One example is the shark scene, which was added to the 1978 version in order to satire the recently released Jaws. There are other big laughs, like in his unconventional method of tennis playing, where he trounces his opponents by playing by a different set of standards and rules, not unlike how he behaves during personal interactions.

There are plenty of little laughs as well, like him painting a boat and the paint can rolls away from and towards him without his noticing. Or the older man who casually throws away seashells as his wife collects them. This is just the tip of the iceberg, as there are countless subtle oddities that Tati throws into the scene, many of which are humorous and sometimes are hidden. He rewards people for paying attention to the details.

There are plenty of other scenes that are not funny, nor are they intended to be, and this is what separates a Tati film from plenty of other comedies. He slows things down and lets the film breathe. This is, after all, a vacation, and he conveys the sense of getting away.

Not all of the characters participate in the vacation. The businessman is constantly taking calls about his stock purchases. A young political idealist is consumed by continually talking about intellectual matters. The characters who interact the moat with Hulot, however, appear to leave life’s trappings behind them. The children take to Hulot, and they are at home away from home, caring only for enjoyment, music and treats. A number of females also take to Hulot, although not so much in the romantic sense. One young, attractive lady finds herself a dancing partner that keeps a comfortable distance. Another older Englishwoman is delighted by the klutzy Frenchman, and she embraces his quirkiness. Even the older couple adore Hulot,and they spend most of their vacation walking around quietly and peacefully.

Those who accept and enjoy Hulot get the most out of their vacation, and that’s because they challenge their comfort zone. They don’t just follow the herd of modern trappings, but they embrace being outsiders and distant from this quagmire of a society.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements:

Terry Jones introduction. The Monty Python member gives a short introduction by Criterion standards and basically highlights his favorite scenes. His presence on the disc speaks more for the influence of Tati. His influence on people like Rowan Atkinson is obvious — the Pythons less so.

Clear Skies, Light Breeze: Critical essay. This is a French critical essay by Stéphane Goudet. She talks about Tati’s art and his comedy, how he embraces the middle class and ridicules bureaucracy and technology. One example is the untillegible speaker at the train station, which people follow blindly. She compares many of these same themes to Tati’s later films.

Sounds of Silence: Interview with Michael Chion. He talks about Tati’s use of sound. The sounds in the film do not fill up spaces, but they are used to complement the space. Tati uses sound to guide our eye to the object (like the swinging door in the restaurant). It enhances the silence. There’s actually quite a bit of sound in Tati films, like the sea in Hulot and the music, and there’s lots of dialogue, but it seems to be primarily in the background.

Cine Regard. This is a French TV program where Tati watches clips from his films and discusses them. He begins by telling a funny story about how he went to a screening of Holiday anonymously, entering in the dark so that nobody would recognize him. He sits next to a man who laughs throughout the film, nudges Tati and constantly calls the director an asshole, not realizing the object of his ridicule is sitting next to him. Tati shares a bit of insight into his films, but it is clear during the discussion that he is protective of their integrity. They are like his children.

1953 version of the film. This original version is not the primary version on the disc, because Tati was a proponent of adapting and improving his films over time, which in my opinion he succeeded with Holiday. Many of the changes are cosmetic, especially with the sound. The older version is busier and slightly more political. The older version is also about 10 minutes longer. Unlike a lot of directors, Tati didn’t mind cutting things out to increase the flow, and he did the same with Jour de Fete.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Criterion: Blithe Spirit, 1945

BLITHE SPIRIT, DAVID LEAN, 1945

Blithe Spirit can easily be dismissed as one of the lesser of the Lean/Coward collaborations, or the inferior of Lean’s two comedies, or the mediocre movie that Lean got out of the way before focusing on arguably his finest masterpiece, Brief Encounter. All of these statements are true to an extent. This is a light, mediocre effort, yet it is engaging and at times pleasurable despite its flaws.

Lost in the comedic ghost story is a great deal of class-consciousness and their virtues, or lack thereof. Charles Condomine states early on that “it’s discouraging to think how many people are shocked by honesty and how few by deceit.” His current wife, Ruth, is shocked by his later honesty, even though she claims that she would not be offended by his calling his dead wife Elvira more attractive. Both Condomines act under the auspices of honesty, but in fact, there is a deceit going on that will be uncovered later.

Madame Arcanti is a lower class medium who travels by bicycle to the Condomines to reach out to the dead for them. She is excited by having some interest in her gift, but she is the object of their upper class ridicule. As it turns out, this is a clever deceit, as they believe none of it, and are merely using her to witness her methods for Condomine to write a mystery book later. Unlike her hosts, Arcanti is completely honest. She even states in a later scene that “honesty is the best policy.” After the ghosts are brought back into the world, she is fascinated by her abilities coming true, yet is clear about her limitations. She is helpless as to how to get them to leave. A lot of unsuccessful trial and error ensues.

Much of the comedy has to do with Arcanti bumbling around during her séances, and later when Charles’ ex-wife appears to his eyes and ears only, and he tries to talk to both her and his wife Ruth at the same time. His current wife is easy to offend, shocked by his honesty, even if it is directed at his dead wife and not her.

Kay Hammond is a delight as Elvira, and her capricious bantering with Charles is when the film is at its most enjoyable, especially since his responses end up with him inadvertently insulting his wife. Elvira relishes in Ruth’s reactions, pulling the strings to drive the couple apart.

Ruth comes off worse as the film progresses, and she seems to represent the worst of her upper class upbringing. She maligns Elvira, referring to her as not having the “slightest sign of breeding.” She does not get along with Arcanti either when she recruits the medium for a solution, and insults the poor woman’s credibility. She proves to be a poor wife to Charles, and the deceit is that she has his best interests in mind. She is thinking of herself only, and the only way to rectify her situation is to rid the living world of Elvira.

Elvira is a unabashed liar, lout, and rarely gives anything but a flippant response to anything Ruth or Arcanti says. She is the spirit that is being described as blithe, which is defined as “showing a casual and cheerful indifference considered to be callous or improper.” Over time, she wears out her welcome to Charles as well, and she admits that even during their marriage, she was unfaithful. She is the queen of deception and the antithesis of honesty.

Despite being occasionally charming, Blithe Spirit can be plodding and tiresome. It is a good thing that Lean made Hobson’s Choice later to prove that he had a comedic voice, although it is unfair to compare Charles Laughton with Rex Harrison on any level. This was a spirited attempt, but more of a stepping stone on the way to better things for Lean’s career.

Film Rating: 5.5

Supplements:

Interview with David Lean scholar Barry Day: Day was also not altogether thrilled with the film, although I don’t necessarily agree with all of his criticisms. He thought that Kay Hammond as Elvira was a problem because she was not as physically attractive on screen as Constance Cummings. Perhaps this is true on a physical role without being made up for the roles, but attraction is not always derived from looks. Her Elvira, however unscrupulous, was more desirable than the square-pegged Ruth. Day concludes that the film is “not bad, but not as good as it could have been.”

The Southbank Show on Noel Coward: This gem of a TV documentary is better than the actual feature, in my opinion. It is a life retrospective of Coward, from his upbringing to his death, and finally to his legacy. Some of the best parts were archived versions of him singing his songs, something I had never seen before. They go on through his plays, the failures and the successes, show him as an actor, and discuss his closeted homosexual personal life. He was unquestionably an interesting and talented man and this was a worthy portrait of him. As for his legacy, one of his later quotes are that he “was not all that keen on being significant.” He may not have been keen on it, but the works stands on their own as being extremely significant.

Criterion Rating: 6/10

Criterion: Richard III, 1955

RICHARD III, LAURENCE OLIVIER, 1955

After tackling Henry V and Hamlet, Laurence Olivier directed and starred in his third and final Shakespeare feature, in spectacular VistaVision Technicolor. Many consider this to be his magnum opus, and as an actor, the character he is most commonly associated with. It has inspired many actors and performances, ranging from theatrical actors to punk rock singers (Johnny Rotten). It is undoubtedly a performance for the ages.

Unlike Polanski’s Macbeth, which I recently reviewed and highlighted that the character’s speeches to the camera were handled via internal monologue as voiceover, Olivier continues the tradition of speaking to the screen/audience as the ‘Vice ‘ character. One can argue which is the preferable method, but in the mid-1950s, the sort of revolutionary direction that Polanski undertook would have been too radical. Not to mention, the film would have lost something special in Olivier’s performance. His finest moments in the film are when he is speaking to us, beginning with the “Now is the winter of our discontent” to the infamous “My Horse!” line – although in fairness, the latter plea was desperately spoken to everyone.

As Olivier puts it, he prefers to work from the outside-in. He develops the look of the character and uses that as his starting point for the performance. In Richard III, he worse a long, dark wig, a prosthetic nose and walked with a hunched gait in order to demonstrate the character’s disability, which could be seen as his evil motivation. He wore brash, ostentatious costumes, which for half of the film made him appear as if a bird of prey. His look was ferocious, and blended together splendidly with the evil nature of Richard’s inner self.

The performance is the cornerstone of this production, and Oliver shines throughout. There are a couple of scenes where he was extra impressive. The two scenes in which he is scorned by, and later seduces The Lady Anne. He goes from being spit on by her after she suspects (rightfully) that he murdered her husband, to being manipulated into loving him. This is one scene in the play, which Olivier cuts into two in order to make it seem more plausible. Even that is a reach, but through the performance and Richard’s urging The Lady Anne to end him, he makes it somewhat believable. It does not hurt that Claire Bloom is up to the task of playing opposite him.

Other scenes that stand out are when Richard goes from a measured speaking voice, to lashing out at anyone and everyone within earshot. His moods were explosive, larger than life, and he stopped at nothing to achieve his ambitions. Yet, he was also a charismatic leader, which was on display at the Battle of Bosworth Field as he gives a rousing speech to rally his troops.

Olivier was not the only star in this vehicle. Sirs John Gielgud, Cedric Hardwicke, and Ralph Richardson. The other performances are more grounded, solemn, and more in tune with Shakespeare’s blend of theatrical acting, whereas Olivier contrasts them with his emotional and tonally flat reading. The peripheral cast are superb, but they are rigid, and upstaged by the flamboyant and electrifying Olivier. This contrast reminded me some of the British stage actors contrasting with method actors in Hollywood. Richardson’s performance in William Wyler’s The Heiress is an example of this, as he had to trade barbs with method actor Montgomery Clift. This enhanced that movie, just as the supporting performances do for Olivier’s production.

The film is not without flaws. Another contrast with Polanski’s Macbeth is that he shot exclusively on location. The majority of Richard III is shot on a stage, which gives it a more theatrical look and feel. Some of the stages were not very realistic, with obviously painted clouds as background and buildings that look like a theatrical production designer could have created them. The Technicolor, while superb for most of the film, makes these facades all the more evident, and at times it feels like we are watching a stage play that just happens to have a camera there.

There are other problems with the middle acts. The beginning and final acts are electrifying. The former is due to Olivier’s introductory speech and stage setting for what is to come, and the finale for the location shooting and the battle action. The middle seasons suffer as being plodding. Following Shakespeare dialogue is difficult without knowing the play already, and the original audience lived in a time where they would be aware of the history, which happened to be told through previous Shakespeare plays. We are not as in tune with that history, and it becomes difficult to follow the machinations of Richard as he consolidates his power by eliminating his enemies. The only obvious end is in a decapitation scene, but the outcome of The Lady Anne and the two princes are more muddled. Since Olivier had taken license with Shakespeare’s words in the beginning, he could have continued in order to make the play more understandable for a wider audience.

That leaves us with Olivier in arguably his best performance and without question his most iconic on film. The film stands up and is remembered because of him, and he carries it through the long running time of 160 minutes. Even though he is an anti-hero and easy to root against, he sparkles when he is on the screen and we want him to succeed just so we can see where his performance will head next. This is my favorite performance of his, but not my favorite film.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements:

Audio Commentary: Criterion has a good habit of using commentaries that complement the film and educate the viewer. Here they use two people involved with the theater, stage director Russell Lees and former governor of the Royal Shakespeare Company John Wilders. While they are educated on the film language, they share details about the theatrical nuances and how they are translated to film. Lees dissects the iambic pentameter style of verse, giving some background into how and why it was used during Shakespeare’s time. He also shows how Olivier deftly plays with the verse to make it oftentimes sound like he is speaking directly, whereas the other traditional actors tend to speak in a Shakespearian manner.

1966 Interview: This is from the BBC series Great Acting, where theatrical critic Kenneth Tynan interviews Olivier as a career retrospective. Olivier is a great subject out of character and talks candidly about various subjects. He does discuss the differences between his and Gielgud’s style, which he defines himself as ‘earthy’ and his rival as ‘spiritual.’ He also speaks about how significant his Richard performance became, and how he modeled the look and demeanor after Jed Harris in as uncomplimentary a fashion as possible.

Restoration demonstration: Martin Scorsese talks about the challenges with restoring this film. One was with the VistaVision print, which most labs cannot scan. Another major problem was that there had been cuts to the film, most notably for the American TV audience. They had to find a Premier print and use that as a guideline for what should be included in the original film, and then re-insert those scenes. In addition the normal scratches and blemishes, there were chemical stains and color fading, all of which had to be corrected digitally. Fortunately we are living in a golden age of film restoration, otherwise we might not be able to see the film as Olivier intended.

Criterion Rating: 8/10