Blog Archives

The Friends of Eddie Coyle, 1973, Peter Yates

The Story of Eddie Coyle is a rough edged movie with stern and serious characters that are either acting out of desperation or opportunism, all the while taking advantage of everyone that gets in their way. Everyone has an agenda, and much of the movie is them taking slight steps to manipulate the situation to reach that agenda.

If there’s any doubt about how rough the movie is, it is quashed early when Robert Mitchum’s Eddie Coyle tells a story about putting his hand in a drawer so that nuns would smash his fingers. He has lived a tough life and circumstances have turned against him to where he’s looking at facing time. Meanwhile his “friends” are either running guns for him or robbing banks.

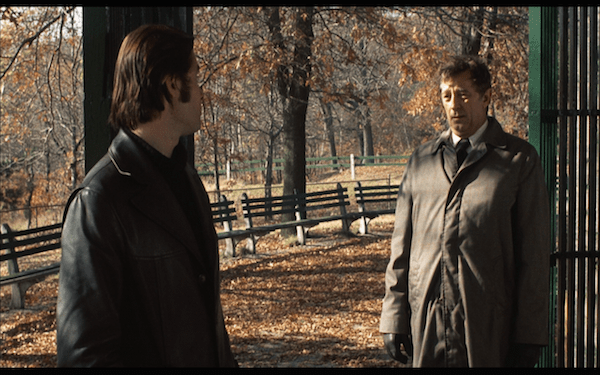

One thing that jumped out at me is the correlations between the uses of space. There are a few tense action sequences, but the remainder of the movie basically consists of people talking to each other at different locations. A great deal of it takes place in the outdoors in the stark daylight, with contrasts with the darkness within each character.

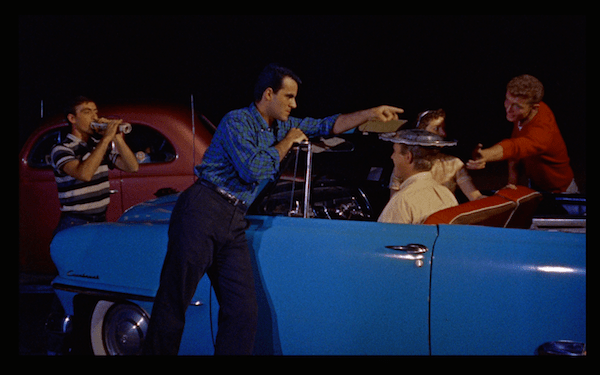

The colors are often vivid pastels, which are used effectively as a way to color the cars for each character. Even on an indoor set like the bowling alley, the bright colors give some vibrancy to what would otherwise be a dark location. They use a variety of locations for these conversations, such as near a riverbank, at a park, in the parking lot of a grocery store or train station, and various other locations. For all the underhanded activity, the template is bright and might otherwise be seen as cheery, but the characterizations and acting keep the film gritty.

Again, using spaces, they differentiate between public and private space. They show Mitchum disheveled at his home. This is a rare glimpse of his private life, but other than him having his shirt un-tucked, it isn’t altogether different that the public spaces we see. It is still brightly lit and he barely cracks a smile, even to his wife who he ushers out while he makes important phone calls.

There are a lot of dialogue scenes with people talking in restaurants, often with Coyle and Jackie Brown (Steven Keats) talking about setting up deals. The diner scene above is a rarity in that it takes place at night, but it still has the same bright lighting, and even adds color with the bright yellow menu reflected on the mirror. It almost appears to be an artificial sun that is hovering above them.

The outdoor night scenes are barely lit, showing emptiness and desolation. There are often long shots with cars driving at night where the only light source is the headlights. This emptiness correlates to the character’s struggles. Many of them are left out to try and are truly alone. They have no real “friends,” especially not Eddie Coyle despite the title. The stark night scenes are not used often and only in important, key situations (like the screenshot above that I will not spoil).

What separates The Friends of Eddie Coyle from many “heist” (if you can call it that) films is the pacing of the “action.” The scenes play out naturally and slowly. This begins with the bank robbery, with many quick cuts to show reactions, slight movements, and the mechanics of the scene. As the pace continues, an unsettling uncertainty sinks in. The slightest movement could make the whole thing go awry, and the viewers are essentially preparing themselves for something to happen. The same sort of pacing is used for the gun exchanges. There’s more action in these scenes, so there is a lot more cutting back and forth, occasionally broken up by characters interacting, and then cutting again as people move into position. Sometimes something climatic happens, while other times nothing happens. It keeps the viewers on their toes. These scenes are wonderfully composed and edited.

Here is where I’ll dip into spoiler territory, so if you have not seen this, you might want to check out now.

The title is meant to be ironic. Eddie Coyle has no friends. Dillon is the guy who seems to be his closest friend and confidant during the movie turns out to have the same motivation as Coyle and double crosses him. Coyle double crosses his other friends, beginning with Jackie Brown, and then he offers up the bank robbers as well – anything that will get him out of hot water. The cops, like Dave Foley, sometimes seem to be looking out for their subject’s best interests, but they are merely playing them. Despite the sacrifice that Coyle makes, it isn’t enough to get him his relief. Dillon makes a greater sacrifice and appears to get his relief, but we will never really know.

Often I try to read deeper into films like this to see what they say about society. The core of The Friends of Eddie Coyle is distrust. Everybody is out for themselves and you cannot trust them, whether you’re in a diner or at a hockey game. Could this be a statement on the Vietnam war that was going on at the time? Could it be related to the Watergate scandal that had just occurred (although to be fair, I’m not sure if that was resolved during the movie)? In this instance, I think there are no deep messages about early 1970s society. It is merely a slick, well-done and somewhat unique crime film, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Film Rating: 7.5

Supplements

Commentary: 2009, Director Peter Yates.

He considers it among his three favorite films that he directed along with The Dresser and Breaking Away.

Yates talks quite a lot about the actors, which is not uncommon with Director commentaries. One of my pet peeves is that they rarely say anything negative. It’s not that I want them to dish on their stars, but I think there could be more substance to a commentary than just gushing about actors. Nonetheless, it was interesting to hear him talk about his cast, especially Mitchum.

Mitchum was the type of guy who didn’t like to discuss his performance in advance, but listens when shooting. He would then adapt accordingly. He wanted to conceive his own ideas first and go from there. Yates said that he was the consummate professional and very impressive. He worked on his Boston accent, and concentrated on holding himself steady to capture the downbeat aura of Coyle.

He said that Boston was very cooperative, letting them shoot in public places and shutting traffic down. Since there were so many public spots, this really made the film.

He considers the film to be the opposite of The Godfather. It was not glamorous or romantic, nor was it about mobsters. It was about morally bankrupt common criminals just scraping along.

This disc is particularly light on features for an upgrade. Other than the commentary, there are image stills. Those are nice, but not as substantial. I would have liked to have seen interviews or a visual essay. Still, because of the quality of the film and the transfer, it is a worthwhile addition.

Criterion Rating: 5.5

On the Waterfront, 1954, Elia Kazan

Waterfront Week was quite an experiment. This is not something I’ve done before but I’ll most likely do it again for important films as they come along.

Here are the posts from the week:

Kazan Naming Names – This is about Elia Kazan’s experiences with the HUAC and how the film is partly autobiographical.

The Great Performances – The film had arguably the best ensemble, and many (including me) would say had the greatest performance of all time. This piece talks about all of the major actors.

My Favorite Classic Movie – After a week of analysis, this is my summary as to whether this stands up as one of the greats of classic cinema.

Film Rating: 10/10

Supplements

Commentary: This is one of the rare occasions where I did not listen to the commentary for this release. The reason? I’ve already heard it. This is the same one from the older DVD. Of course it has probably been 15-20 years since I heard Richard Schickel and Jeff Young talking about the movie. I remember good things and it most likely enhanced my appreciation.

Martin Scorsese and Kent Jones: 2012 interview with the pair who had together made the documentary A Letter to Elia.

Scorsese had a connection with this period of American cinema because it reflected the world in which he lived and grew up. Other movies were still just generally correct. On the Waterfront and Kazan films captured the realism.

They talk about the how the performances moved them and, of course, the HUAC. The part that relates to Kazan’s testimony is the least convincing to Scorsese. He was not aware of the political situation when he first saw it, although he knew the paranoia and controversy from growing up during the time.

Elia Kazan: An Outsider: 1982 documentary directed by Annie Tresgot.

This documentary has Kazan primarily telling his own story. It starts with a house in CT that he acquired in 1939 through his acting. He then got another role, another piece of property, and became a director. He joked that his Greek background had taught him to buy land for security, and once he had that, he could take risks.

He talks about his origins in theater with the Strasberg school, calling it essentially human, rooted in psychoanalysis where people train themselves to be in control of their emotions. Objects are essential.

He reflects on his life as a Communist and the HUAC. He recalls the specifics of how he was voted out of the party (22-2). Afterward he had still been enamored with Soviet Union until the truth of what they had been doing came out, especially the German pact.

He says he was not pressured to testify, but instead had conviction. Solzhenitsyn’s and Kruschev’s books had a major effect on him. The experience changed his life and toughened him. Even though he was in pain from the alienation, his films got better after he testified.

”I’m Standin’ Over Here Now”: 2012 Criterion documentary that has interviews with a number of Kazan scholars and film historians.

He began his theater career with Thornton Wilder’s “The Skin of My Teeth,” yet later directed Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams. One difference between he and other theater directors is that he would engage with the playwright’s on the creation of the play.

The first draft of anything resembling Waterfront was Arthur Miller’s “The Hook” about gangsters in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The studios got cold feet because of Miller’s communism. Miller left project.

Boris Kaufman was chosen as cinematographer. He had worked with Jean Vigo and others, and was chosen because they wanted images of realism. Kaufman and Kazan had a great rapport and cohesion with each other.

As for the allegory of the HUAC controversy and Kazan’s testimony, most people at the time did not make the connection. They say most people today do not make the connection because the time is past (Of course I disagree). Kazan said belligerently that it was about his testimony because he was proud. Budd Schulberg, the screenwriter, argued that it had nothing to do with either testimony, that it was based on a true story.

Eva Marie Saint: 2012 Criterion Interview.

Her routine during the film was that of a housewife. She would go home, make dinner, go to work, come back home, etc. Previously to the film, she and Brando had done improvisations before, but had not acted together before. She was shy about doing the love scene while wearing a slip on camera, but Brando took her aside and whispered “Jeff” – her husband’s name. It worked and she was relaxed.

Elia Kazan: 2001 Interview with Richard Schickel.

Kazan humbly calls it a wonderful screenplay with a wonderful actor, and that’s why it worked. It was a great experience for him and the closest he came to making a film exactly as he wanted.

He talks about the cab scene and how it has become so popular. He takes no credit. All he did was take the two characters in the backseat of a barely assembled set. They knew the characters and they made the scene.

Thomas Hanley 2012 Criterion interview with child actor from the pigeons. His story was interesting because he retired from acting and became a longshoreman. He was the real deal.

His father was killed and was no saint, but he was never sure why. During the emotional scene, Kazan irked him by suggesting his father was killed for squealing. This was before he did the “pigeon for a pigeon” scene, otherwise he would have tried to portray his character with more toughness.

His career choice was to go on the waterfront or enter a life of crime. He forged his documents, got his coast guard pass, and passed through the waterfront boards.

The reality on the docks were as portrayed in the movie. People didn’t squeal. People got killed. Mobster activity existed, but eventually they would rat on each other. Because of this double standard, now Hanley has no qualms with informing to police.

Who is Mr. Big? 2012 Criterion interview with James T. Fisher, author of On the Irish Waterfront, about the historical basis for the film.

Irish immigrants that came over in the 1820-30s had limited opportunities. Many worked on the docks out of necessity because of danger and it wasn’t a job in demand. They made it their own and achieved political power. Bill McKormick and his family controlled all the ports by early 20th century. McCormick came to be known as “Mr. Big.” People were taken care of as long as they accepted the system, which was not beneficial to them. They had low wages, danger, just as it was portrayed in the movie.

Father Phil Carey tried to achieve social justice for these employees. He received intimidating calls immediately and was warned to stay away. He was even intimidated by the monsignor.

John Corridan was an assistant to Carey who held similar convictions. He spent two years studying the waterfront. He understood the system, bosses, etc. There was a journalist at that time named Malcolm Johnson doing some investigative reporting. Corridan spilled everything to the journalist and blew up the waterfront. Johnson won the Pulitzer and Corridan became a celebrity.

Contender: Mastering the Method: 2001 documentary about the famous scene.

Rod Steiger, James Lipton and others were interviewed.

They really had a makeshift set, which half a taxi, a steering wheel and a seat for a driver. This was a way of cost-cutting. Brando was upset because there was no rear projection, so the instead used blinds because they had seen that in other taxis.

There were three shots. One was straight on both actors together, and then they shot from each actor’s perspective. Brando left for an analyst appointment while Steiger was shooting his part. This bothered Steiger and he wanted to prove himself. That’s part of the reason why he feels he brought such a goof performance.

Strangely enough, Brando did not think he was good in the film. Although a brilliant actor, personally the man was an enigma.

Leonard Bernstein’s Score: 2012 video essay for Criterion featuring Jon Burlingame.

They wanted Bernstein for his star power, not for what he could bring to the movie. He had never scored a film before.

It was rare for the time to start with a single instrument, which was a lone French horn with a few other quiet instruments gradually joining in. Bernstein called it “a quiet representation of the element of tragic mobility that underlies the surface of the main character.”

He composed numerous themes, including ones for Terry Malloy, violent scenes, and the love (or “glove”) scene. He also was able to add music for the cab scene, which was initially going to be played without music. Bernstein’s score begins when gun is pushed away. It is similar to the earlier, sad dirge used at the cargo scene.

Was there too much music? Schulberg said that at times it seemed loud, but he loved the score. The critics loved the score as well, although it lost to The High and Mighty, possibly because Bernstein was not part of the Hollywood industry. The music for On the Waterfront is remembered now far more than any of the nominees.

On the Aspect Ratio: Initially it was projected at 1:85. This was during the origins of the transformation from 1:33, so camera operators framed for both aspect ratios as a way to protect and make sure the film could be seen somewhat correctly in all theaters.

There has been a debate as to which should be the correct aspect ratio. 1:66 is the most common and is on the primary disc. The movie changes at 1:85, with some things being cropped. During the cab scene, the zoom is even more intense and sometimes the faces fall out of the frame during close-ups.

The Criterion disc has all aspect ratios available to watch. Needless to say I did not watch the movie three times for each ratio, but next time I may try a different one.

Even without watching the commentary, this disc has the most supplements that I’ve seen (yet) on a release. It is a worthwhile package that does justice to an historical film.

Criterion Rating: 10/10

An Autumn Afternoon, 1962, Yasujiro Ozu

An Autumn Afternoon ended up being Ozu’s last film. While it is a shame we don’t have a few more Ozu films in color, this was a solid ending to a legendary and masterful career.

For those who have seen Ozu films, the style is completely familiar. It focuses on domestic issues, is shot from a low angle with a camera that never moves, has a somewhat slower pace, and speaks solemnly on the intricacies of life and relationships.

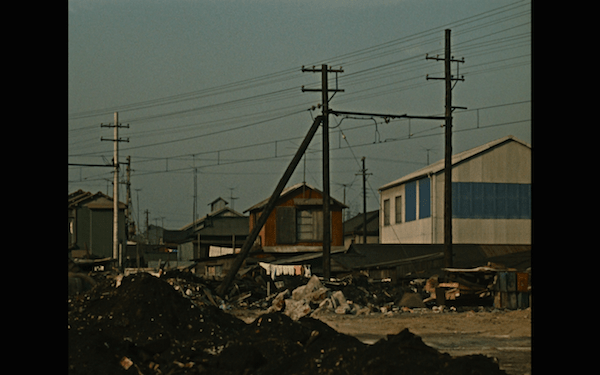

Ozu has plenty to say about the contrast between modernity, technology, commercialism, and a nostalgic fondness for the way things were. This is mostly established by his clever use of transition shots. The character scenes take place almost exclusively on interior sets. The transitions between these scenes show both a commercially vibrant Tokyo with elaborate signage, and also a worn down Tokyo by the seedier side of industry. These images are juxtaposed by characters that are concerned with baseball, refrigerators and golf clubs. Materialism is a vital part of their life, but is not portrayed as an entirely positive thing.

Ozu portrays men drinking together as pleasant experiences. This is where the men relax and enjoy each other’s company. Whether this happens as a large class reunion, or just two fellow Navy officers flippantly discussing the ramifications of the war, the mood is positive. This is punctuated by the score, which like most Ozu films, is always effective at setting a mood. Most trivialities are forgotten as men drink sake in the bar, reliving and enjoying the younger days while playfully tweaking each other. Age and virility are constant topics in these exchanges, and they talk often of marriage. Over time, these exchanges re-direct back to the family and the primary theme of the film. The tragic character of ‘The Gourd’ joins the classmates at their reunion and he is the picture of a fractured life, one that they do not want to repeat.

With Ozu there is always juxtaposition, and that is with family and married life. The family life is often portrayed as structured, formal and with a balance between commercial indulgences and domestic responsibilities. There is a subplot with Shuhei’s married son who wants an expensive set of golf clubs, which his wife stubbornly resists out of economic necessity. Even though marriage is discussed often in the film, this give-and-take exchange (which happens to be among my favorite sequences) shows a marriage in action. The golf clubs provide for a mild conflict between husband and wife, but also a way of expressing how aging men yearn for a leisurely outlet, which the wives must accommodate. This is juxtaposed with the Shuhei’s daughter taking care of her father, while being defiant when it comes to being the caretaker, knowing all along that her father and brother need a strong female in their lives.

Near the mid-point of the movie, after the marital dispute is resolved, the movie is basically rebooted. We see an image of a train, common in Ozu films, and then we see the same images and sets that began the film. We see the candy striped tanks of industry, followed by another exchange between Shuhei and his secretary. This is what started the film, and will propel it to the final act, which is that of Shuhei coming to terms with his aging and accepting the loneliness.

The ‘Gourd’ shows back up and is the catalyst for the remainder of the film. He is pitied, as he has degraded into a drunken restaurateur that caters to the lower classes. As he gets drunk, he laments on his life. “You gentlemen are so fortunate. I’m so lonely,” he says, and then later gives the fateful, tragic line of dialog that finally shakes up Shuhei: “In the end we spend our lives alone.” The former teacher has clung to his daughter, not letting her marry, yet he is still lonely. Shuhei has hitherto been in denial about his daughter’s readiness for marriage, which probably has to do with his reliance on her as a widower. He decides to let her go and let her marry.

The second half is heavier on plot, and as the pursuit of a suitable marriage candidate is explored, we lose sight of where Shuhei is headed. He is kind, thoughtful and considerate of his daughter, who we learn really does want to marry. She does not get her first choice, but she finds a satisfactory match. Her father just wants the her to be pleased with the best possible match.

Shuhei is left alone. After marrying off his daughter, he says: “Boy or girl, they all leave the aged behind.” His solace is working, drinking in bars and re-living the past with friends, whether they are his old classmates or war buddies. At the end he says that, “I’m all alone,” and subsequently sings the war song.

The ending is bittersweet. His family is happy and he is left forgotten. Even though he did the opposite of ‘The Gourd,’ both by finding a lucrative career and letting his daughter go, his fate is the same. Ultimately he has done the right thing, even if it leaves him with the inevitability of aging alone. At least he has solace in his war songs and the knowledge that, contrasted with ‘The Gourd,’ his family is his legacy and they have a bright future.

The same could be said for Ozu. He passed away the year after this was released, and western audiences did not discover him immediately, at least not like counterparts Kurosawa and Mizoguchi. He had a long and illustrious career, but one that was not compromised by intervention or commerciality. He did right by his films, and left a body of work that would stand the test of time.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements

Commentary: I was pleased to see David Bordwell. He is among the most reputable and admired film scholars out there. I have read him many times in film studies classes, and one class used his work as a textbook. Among his many books is Ozu and the Politics of Cinema, which is available as a downloadable PDF. He is one of the foremost Ozu and academic film scholars.

This is one of the better commentaries I’ve heard on a Criterion disc. Bordwell provides a wealth of information, not just on the background of Ozu and the film, but also about the shot selections, filming style, and how they were to used to convey Ozu’s thematic messages. One example is during the golf sequence with the brothers and sister-in-law, which Bordwell demonstrates with precision all the different cuts and camera changes, and how these interact with the relationships.

I’ll share a handful of factoids that I found interesting:

- Ozu establishes the premise early on during the office scene with his secretary. Women have two options in life. They can stay at home with their parents (father) or get married.

- In this era, working class men often had a rhythm of going to work, spending the evening out drinking, and return home drunk.

- It is a misnomer that American culture began penetrating Japan in the 50s. It actually started in the 20-30s. Ozu brought that into his earlier films. Kids in his 1930s films, for instance, want baseball gloves.

- The reunion of characters is also a reunion of actors. Many of those at the reunion were regular Shochiku players.

- Film was in decline during the final years of Ozu’s life. There had been a billion annual movie viewers in 1959, which declined to 500 million in 1963. That mirrored the decline of the prior decade in America. Part of the reason was TV, while foreign imports (especially American) also contributed to a decline in Japanese cinema.

- Sometimes Ozu mismatched the music. He would show a somber scene with cheerful music. Ozu was quoted as wanting “good weather music always.”

- Ozu filmed from a variety of different character ages, genders and perspectives. Most directors rely on autobiographical experience when portraying characters, but Ozu lived at home with his mother for most of his life, so it is impressive that he was able to relate to so many people different than himself.

- Ozu’s camera is almost always lower and rarely moves, but it is not on the floor. It is just lower than the characters in the frame, so the viewer is barely looking up.

- Ozu checked every shot through Viewfinder. Shohei Imamura was AD and got annoyed by him playing with continuity. Ozu uses it in this film with a soy sauce bottle, which Bordwell compares to a subtle Jacques Tati gag.

- Ozu’s mother died during production of film. Bordwell reads his diary entry where writes a poem beginning with: “Under the sky spring is blossoming ….” His grief materializes in the movie, with the film about a father also possibly being a film about a son.

Yasujiro Ozy and the Taste of Sake: 1978 excerpts of French TV show.

Ozu was “mysterious in his simplicity.” They talk about how he was a bachelor that lived with his mother for 60 years. He was usually later than his contemporaries when adopting technologies, including sound and color. He was unknown in the west until 15 years after his death.

A number of French critics discuss the filmmaker and his films. Georges Perec says Ozu searches for reality and does not find it. Instead he questions reality.

They show sequences of archery, Zen Buddhism, philosophy and even martial arts, which are prerequisites for Ozu’s work.

This release is an example that quantity does not always equate to quality. Usually a movie with a commentary and a single supplement would not be considered a major release, but the quality of the commentary and the gorgeous 4k restoration make this a must for any Ozu fan.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Beauty and the Beast, 1946, Jean Cocteau

When Beauty and the Beast was in production, the Second World War was in its final throes. The entire European landscape was ravaged and devastated by the war machine, and France had been under German occupation. Even though many filmmakers fled or were exiled, the industry continued in a limited capacity. To say that it had been a difficult time for the French would be a gross understatement. It had been horrific. When the film industry slowly began finding its legs, it would be expected that some escapism would be necessary. A bit of that can be found in Children of Paradise (my #1 of 1945). Few, however, would expect such a vast departure from reality as Beauty and the Beast.

Previous to 1946, Fairy Tales had primarily been almost exclusive to Disney animated films. In France, they were even less prominent, as many American films had not been shown during the war. Most people didn’t have a chance to see Pinnochio, Fantasia, Dumbo or Bambi until after the war. I’m a believer that time and context is a major consideration when evaluating film. This makes Cocteau’s project that much more special. For France, it was revolutionary filmmaking, unparalleled in time and space. One could argue that there never has been a live action film like it, and it has influenced many future films, such as the Disney remake and Demy’s Donkey Skin.

The story is familiar to probably every reader. Whether they have seen the Cocteau, they have undoubtedly seen the 1991 Disney version, which takes more from Cocteau than it does the original work from Beaumont. A princess ends up in an animated castle with a beastly creature. At first she loathes him, but grows to like and respect him, and eventually, well, you know the rest. This is a fairy tale after all.

What is also impressive is that Cocteau does not rely on state-of-the-art special effects to achieve is fantasy. He uses set design, musical score, costumes, make-up, cinematography, and mise-en-scene to create the fantasy. There are special effects, but they are only slightly more technical than the effects that Georges Méliès was creating during the early days of films. What’s more impressive is that we hardly notice that the effects are not technical spectacles. Everything else is so well done that it keeps us enthralled with what’s on screen. Cocteau uses artistry and not trickery to immerse us in this world.

I’ve already gushed plenty about this movie, but I have to gush just a little more. Jean Marais deserves credit for playing a number of parts in the film, but most importantly for his work as the Beast. One amazing aspect of the supplements was learning all that went into creating the character. Marais basically had to live in an uncomfortable layer of fur for hours, after spending up to five-hours being prepared in costume. Despite having no face to emote, he manages to perform enough with his eyes and his mannerisms that we understand the character’s feelings and motivations. On different occasions, we see the Beast as fierce, menacing, somber, mournful and jubilant.

Unlike a number of directors, past and present, Cocteau was a true artist. Rather than create a faithful adaptation, he made it his own by adding to the fantasy. The fantastical elements of the house are all Cocteau. He has human hands holding candles, pouring liquids, and human faces lining the walls, watching every move of the living. The fact that the house is alive adds to the mood and mystique. It is both unnerving and enticing to see a ashen face breathing smoke alongside the fireplace.

Beauty and the Beast was not without social commentary. The fact that the other living characters, especially Belle’s sisters, are untrustworthy, manipulative, and only looking out for their own gain speaks to the times. Belle utters a particularly scathing line of dialog that speaks more to modern society, specifically German occupiers and French collaborators: “There are men far more monstrous than you, but they conceal it well.” Cocteau is unequivocally comparing the monstrous nature of the peripheral characters with the real monsters who had governed France for the previous several years. Even if these monsters could sometimes be polite and smile, that does not change the fact that they are monsters. Beauty’s first paramour, Avenant, is very much like these two-faced fiends. He even has Belle fooled during the early portion of the film, but he is revealed to be just as cunning and dangerous as the outwardly evil characters. The Beast may not look like much and acts outside of social norms, but he is genuine. Belle knows what she will get with the Beast, and the more she gets to know him, the more she likes what he is.

I’m careful not to use the word “masterpiece” because it is a term that is too easily thrown about. I’ve used it on a few occasions, which is probably too often because it lessens the magnitude of the word. When I consider something is a masterpiece, I believe it is a truly original, creative and artistic piece of work that is unparalleled. Beauty and the Beast meets my definition, as I consider it the most important and the greatest live action fairy tale that has ever been made. It is the standard for which all tales should be measured, animated or otherwise.

Film Rating: 10/10

Supplements

Commentaries:

Arthur Knight – Film historian, recorded in 1991.

- Germans enjoyed the film. They took to the Aryan looks of the leads and ignored the subtext, although it was obvious in the minds of the French.

- Cocteau added a number of elements to the story. Avenant is an example of a character that was not in the original.

- It was a frustrating shoot because of continued problems. Airplanes would fly over the set, the weather was bad, and passing children would gawk at Marais in costume. There were many delays.

- Cocteau was critical of Alekant’s cinematography, especially the pacing of him setting up, thinking that imperfections would show in the final product. The opposite was true as the photography was celebrated.

- Knight speaks in detail about Cocteau’s homosexuality, contrasted with Noel Coward’s. He speaks about the relationship with Jean Marais, which lasted until 1947, where Cocteau met Edouard Dermit.

Sir Christopher Frayling – Writer and cultural historian, recorded in 2001.

- He gives more of a direct commentary to the scenes as they are shown whereas King provides more background details. Frayling mentions more instances where Cocteau takes poetic license or when the dialog is lifted from the book.

- Critics had attacked Cocteau for not being political. The prologue text is directed more toward them than the viewer.

- Cocteau had been poet, playwright, graphic artist, and a novelist. He was quite the artist, but hadn’t made a film since 1930 and this was his first mainstream film.

- Many of the castle props, including the living sculptures and supernatural elements were inventions of Cocteau. This is more surreal whereas the book was opulent. Disney used the Cocteau ideas for their version.

- Frayling contrasts between Beauty in this version and Disney. She is a post-feminist, intelligent woman in the Disney film, whereas Cocteau portrays her more as an object.

- In original story, Belle stays with Beast for three months while sisters get married to flawed individuals. Cocteau compresses the scenes.

- The fairy tale dates to 2nd century AD and wasn’t written until 1756. Passed down via word of mouth – “mother goose tale.”

- New Wave filmmakers loved Cocteau and Truffaut actually donated money for him to complete a film. He was not embraced in 1946-47.

Philip Glass’s Opera: 1994 opera created for the movie. It functions as another audio track that replaces the dialog. The Glass music is distinctive for those watching Errol Morris films (link to Thin Blue Line). It is a nice option for fans of opera and highlights some of the emotionality of the film. For many it may be the preferred score. It is extremely well put-together and inspired, but I prefer the original.

Screening at the Majestic: A short documentary about the filming with interviews.

During filming in 1946 in Rochecorbon, Tours, Cocteau watched the “rushes” in the Majestic Theater, which no longer exists. They found from the rushes that the film had a poetic and beautiful quality.

Jean Marais (Beast) and Mila Parély (Félicie) are interviewed. Marais respects Beaumont, the original author, but thinks that the magnificence of the film is due to Cocteau. I agree.

René Clément showed up and assisted, just after finishing Battle of the Rails, a prominent movie about the French Resistance. Clément was an AD, but was vitally important. They did not know then how talented he was.

Marais’ makeup took 5 hours to put on and was difficult to take on. The glue cut off his circulation.

Studied the art of Vermeer and others to get the lighting and set design. This is apparent in the scenes of Belle’s family’s house, as the interiors look very much like Vermeer paintings.

Interview with Henri Alekan: This 1995 TV interview with Director of Photography coincided with restoration.

It was a highlight of his life, in part because he was a beginner. It was difficult to make because the war was still going on.

Tricky to film in the dark, but he took on the challenge. Flemish painters like Vermeer, De Hooch, inspired him. Cocteau mentioned them repeatedly and encouraged him to go to museums to study the masters. This was just as important for his future as a cinematographer as making the film.

Secrets Professionnels: Tête à Tête: 1964 episode from French TV.

This short feature is about Hagop Arakelian, makeup artist. He worked for 33 years in the profession, learned from an actor in stage and silent movies in Russia and France.

As he has an actor in the make-up chair, he talks about his methods for applying makeup, how to make eyes look natural and other practices.

The list of directors he has worked with is staggering. They are basically the masters of French cinema. He demonstrates a number of different looks he can create, such as a black/white painted male face or a vagabond looking character with fake facial hair

This piece does not mention Beauty and the Beast, but he refers to it as his best work.

Film Restoration: The movie was not in jeopardy of being lost because all the negatives exist, but had degraded over the years. They replaced 150 frames with those before or after to fill in black frames, while computer procedures were used to correct sound.

Criterion Rating: 10/10

The Thin Blue Line, 1988, Errol Morris

Before there was Paradise Lost, Serial or The Jinx, there was The Thin Blue Line. Even if it was not the first true crime in media (America’s Most Wanted’s debut was the same year of its release), it feels like it. A good argument could be made that it is the most influential crime documentary of all time, and it has influenced countless other crime stories, not to mention documentaries in general. In addition to being revolutionary from a filmmaking perspective, it also set the pace for criminal advocacy filmmaking, which has successfully brought attention and scrutiny to victims of the justice system. In many cases, including all of the ones I’ve cited in this paragraph, it has contributed to revelations in the case.

That’s not to say that The Thin Blue Line is not without controversy. It broke a cardinal rule of documentary filmmaking by actually reenacting the crime and other situations. Of course the idea of cinematic purity is a silly one, and I’ve debated it already when discussing My Winnipeg. Plenty of celebrated filmmakers have played with their subjects and shown things that are not true. Whether they are the staged actors of Robert Flaherty or the deliberate interaction between the filmmakers and subjects in Harlan County, USA, that line has been blurred many times in the past.

Errol Morris played with the truth by re-staging the murder, hiring actors to portray the key participants, including the two police on the scene, and the one (or two) alleged killers. This may not be “true” cinema or “vérité,” but in the case of this film, it enhances the understanding of the crime. If we just had talking head interviews or court transcripts to describe the events, the film would be bland and the crime difficult to visualize. Morris is getting the most out of the visual nature of film. Plenty of documentaries have done the same thing, including the Serial podcast, which tried to reproduce of the events of their subject to see if they fit the alleged timeline. Together with one of several great Philip Glass scores to Morris movies, the restaging makes for a more watchable documentary, while still having enough interviews and testimonials for credibility.

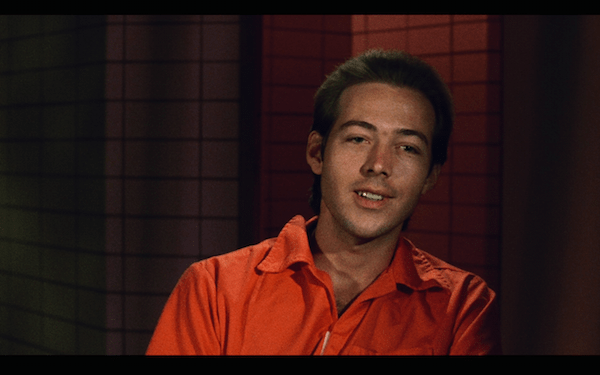

What happened on the night of November 27th, 1976? That’s what Errol Morris endeavors to uncover. He tackles the case with vigor and sheds light on the political and judicial process that allowed for a man to be convicted when he claimed he was innocent. When the film begins, we learn that a car was pulled over by the police, and officer Robert Wood was shot dead when he approached the driver. He had a partner in the car, but her view and memory of the incident would not conclusively lead to the killer. Instead the police relied on the testimony of David Harris, a 16-year old kid, against Randall Adams, a 28-year old that had recently moved to Texas.

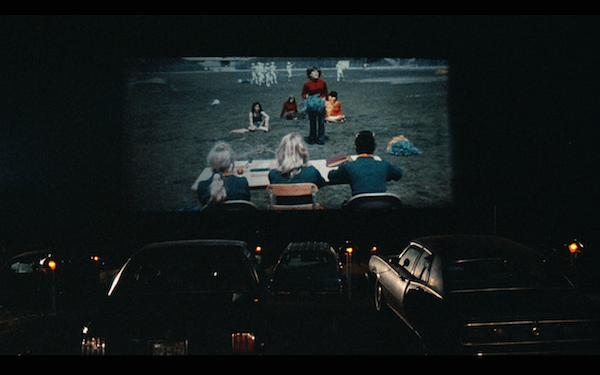

Morris spends a great deal of time talking to Harris and Adams, both of whom are in jail. They tell their version of events on the day, but their interviews, like David’s testimony and Randall’s statement, do not match up. Adams insists that he was innocent. He says his car ran out of gas earlier that day. Harris picked him up in a stolen car, and they spent the day together drinking, drugging and later going to a drive-in movie. Adams says that he went home afterward, whereas Harris says that they were still together and Adams was driving when the incident occurred.

Morris does not stop at just the victims. He explores the entirety of the Texas judicial system, particularly how they are obsessed with the death penalty. That is why Adams thinks he was ultimately convicted because, as he put it, the D.A. “wanted to kill me.” Since he was older, he could be given the death penalty, whereas Harris was a minor so the chances were slim. With this being a cop-killing and a frustratingly unsuccessful and prolonged investigation, the D.A. put together a flimsy case and achieved a conviction. According to Adams, the system was more interested in clearing the case than finding the truth.

One man’s word against another is not usually enough to get a conviction. Adams was a suspect and gave a statement, which was transcribed on a typewriter. Morris again reenacted this for the screen. It is one of many examples of him using a visual, filmic element to reveal part of the story. Adams’ statement only said that he and Harris were together, but did not touch on the events later in the evening. Adams signed it, and it was considered to be close to a confession. The newspapers even reported it as such.

During the trial, eyewitnesses came forward. Morris had unfettered access to most people in the case, including the attorneys, the judge, and some of the witnesses. When Morris puts the eyewitnesses them in front of the camera and asks frank questions, he gets surprising answers. Even if Adams was guilty, it is clear that this was not a open and shut case. There were issues at every stage of the process, from the investigation to the prosecution.

Why would people go to such lengths to obtain a conviction? Why would people compromise their integrity to put someone away? Unlike his later films, we don’t see or hear Morris on camera, but we can tell that he asks tough questions and gets revealing answers. We get an idea why the witnesses testify. Was it because they had some self-interest or because they legitimately witnessed the crime? That depends on who you believe. As to why the police were invested in a conviction, well that is answered with the D.A.’s opening statement. He says that there is a “Thin Blue Line” that protects the people from anarchy. That line has to be protected. Adams would say that they were doing the opposite by turning away from the truth.

The great thing about this movie is not only that it asks the questions, but it also provides answers. Yes, it provides THE answer. It is not a clear “so and so killed him in such and such way.” It is a veiled and carefully worded statement, captured on an audio recording. The image of the tape recorder playing back that interview is the most memorable and shocking of the entire movie. By the end of the movie, we know who killed Officer Wood. I will not reveal it here because the movie is a must see, but I will say that people’s lives were changed as a direct result of that tape recording and this film.

Film Rating: 9.5/10

Supplements

Errol Morris Interview: When I first read about the supplements on this disc, I was disappointed that there was not a commentary. When I got to the 2014 Errol Morris interview, that disappointment vanished.

Of course he would do an interview. That’s his thing! And he made for a fascinating subject, and probably provided a great deal of information that would have been on the commentary, but through the interview format, he is able to retell it as stories. The 40-minutes went by like lightning. It was fascinating hearing his experiences. I actually took about 600-700 words of notes while watching, which is far too much to write here. Plus I don’t want to spoil what he says. Instead, below is a list of the topics he delves into:

- The reenactment. He explains why he chose this method and what he hoped to accomplish.

- He talks about his background as a Private Detective and how this influenced his work on the film.

- He talks about his exposure to the Texas justice system through meeting another subject.

- He discusses his first impressions of the trial transcripts and the case when he first began considering this as a topic.

- The most fascinating part is when he talks about how he interviewed the person that would later be revealed as the killer. He immediately knew the truth when meeting this person and tells a story of how he feared for his life.

- He talks about the witnesses, especially Emily Miller.

- He delves into the film’s ending and his feelings about his findings.

- He talks about the aftermath of the movie and his relationship with the subjects.

Joshua Oppenheimer: Director of The Act of Killing.

Oppenheimer is a young documentarian, but he earned a lot of credibility with his first feature film. Like many documentaries (or one might say almost all), it owes a great debt to Errol Morris. He says that to call The Thin Blue Line great is to diminish it. The movie redefined the idea of a documentary.

Oppenheimer talks about the idea of using reenactment as a way to “excavate layer upon layer” of the story. In the film, we never see what really happened. Frankly, we never really know. We see incorrect versions based on whoever is telling the story. This shows that the participants are telling lies, but they believe their lies.

He also addresses direct cinema, the filmmaking style of the reenactments and his overall impressions. This is a shorter interview, but it is enlightening

Today Show: This is a 5-minute segment with Randall Adams, Randy Schaffer and Errol Morris. They talk about the aftermath of what happened and how the experience impacted all of their lives.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

The Blob, 1958, Irwin S. Yeaworth

As I watched the original version of The Blob, I was surprised to find that it is just as much a teenpic as a monster movie. In some respects, the teenage themes were even more integral to the story. The monster was as much a vehicle to showcase adolescent insecurity, conflicts with authority, and the frustration of not being heard.

The teenpic nature of the film actually fits wonderfully for the way I want to structure this blog post. Since I’m about to get going on my Blobathon, it seems fitting to have a serious post today about the teenage issues, with a fun and light post on Wednesday about the monster itself. The Wednesday post will also contrast with the monster of the 1988 version of The Blob.

The one hurdle is that you have to buy Steve McQueen, in his debut feature role at the age of 27, as a teenager. That’s the biggest sell because even then he had a grizzled, experienced face, which would serve him well in his later stardom. While it takes a little while to get used to him as a teenager, he does show signs of the acting chops and screen presence that he’ll become famous for later.

What’s interesting about the teenage protagonists in The Blob as opposed to say, Rebel Without a Cause or even Blackboard Jungle, is that the kids are relatively benign with their misbehavior. As the plot progresses into a monster mystery, the actions that would usually be associated with young hooliganism, like sneaking out with a girl or driving cars fast, are actually heroic actions in an attempt to save their town.

The film begins with Steve (Steve McQueen) and Jane (Aneta Corsaut) up in his convertible at a lookout, gazing at the stars and enjoying each other’s company. This is a stereotypical scene of the 1950s, and usually would be seen as a place where a man would bring a girl, or a series of girls, in the hopes of one day getting lucky. Jane questions Steve on this very possibility, but he assures her that she is the first, and that he will not pressure her for romance. Even if he’s a teenager with normal hormones, he is established immediately as upstanding.

The next major scene between the teenagers is also typical juvenile behavior – a car race. A group of kids at first seem antagonistic, and they even tease Steve by dubbing him king of the road and placing a hubcap crown on his head. The tension eases quickly. They become more congenial, and even though they race, they do so in a playful spirit and the sequence ends with them friendly towards each other.

The relationship with the teenagers and the policeman are quite different from the norm. This being a small town, they know each other, and Steve addresses the ‘good’ cop as Dave rather than officer or any other title of respect. The ‘bad’ cop, Jim Bert, is nicknamed ‘Bert the Schmert’ because he is not sympathetic. Instead he is hostile and antagonistic. He refuses to believe in the monster, and blames juvenile delinquency for the strange events happening in the town.

The monster places the kids in a hopeless situation where they are the only living witnesses, but absolutely nobody will believe them. There are a few scenes where they try to convince the police. Dave is more inclined to believe then, whereas Bert plays intermediary and sways attention back onto the kids. Bert is alone in this manner of thinking, but this still contributes to confusion. The police and everybody else don’t know what to believe. There is another scene where a kid tries to warn a group of adult partiers, but they dismiss him entirely, even making fun of him by calling him Paul Revere. After several futile attempts to make people aware, Steve frustratingly wonders “How do you protect people from something they don’t believe in?”

They don’t get results until Steve and the other teenagers make enough of a ruckus to get the entire town out of bed and gathered in one area. They do this via another method of teenage misbehavior — honking their horns and making noise. Steve then appeals yet again to the police. This time Dave is a willing listener. He takes a leadership role that leads to the final outcome. The tables are turned and the adults actually save the children.

Given that this was a B-level science fiction escapist flick, with a director who had never made a fiction feature, and a lot of amateur or first time actors, The Blob overachieves. The shots may not be framed well and the editing has some issues, but the story is told effectively. The teenage themes help the audience get more invested in their fight against the red menace, and it makes for an enjoyable resolution.

Film Rating: 6/10

Supplements

Commentaries: This release has two commentaries, one with Producer Jack Harris and Historian Bruce Eder, and the other with Director Irwin S. Yeaworth Jr. and Actor Robert Fields. All of the commentaries are recorded separately with no interaction, so I’m just going to list some of the highlights from each. One of the interesting highlights was how each one talked about the late Steve McQueen. They all spent quite a bit of time talking of their experiences with him, whether positive or negative. He was certainly a character, both on and off camera.

Jack Harris – Harris of course wanted to make a commercially successful film, so he intentionally combined science fiction with a teenpics. Both were playing well at the time, so he figured it would be a winning formula.

He thought McQueen had potential to be a big star, but he was too much of a “bad boy” and trying to impress people. Harris admitted that he didn’t like Steve McQueen on The Blob and would not cast him in the sequel. By the time he changed his mind, McQueen was too big for them to afford him. They became cordial later and McQueen tried to rent Harris’ house once. That was the last time Harris saw him.

He is the only one on the commentary to address the 1988 remake. He was not complimentary. The remake went in a lot of directions that the original didn’t, was too expensive and not as good.

Bruce Eder – Eder did not get as much voice time as Harris, but he did get a chance to make some Illuminating points.

He discusses some of the teenage themes. The children are the only ones who see the Blob until the end, and the police think the teenagers are the invaders. Eder thinks that McQueen’s performance came across as real on the film because he had genuine problems and irritation with the script. Those negative feelings were expressed through his performance as he tried to get heard.

Irwin S. Yeaworth Jr. –

McQueen and Yeaworth were both about the same age, and one review called them “the world’s oldest teenagers.” He had previously worked on a number of religious and educational films. They had created about a hundred 16mm films before trying their first feature.

He says that McQueen had a mercurial personality and was very “willful.” He hints at some problems on the set, although they did see each other several times later in California until Yeaworth stopped working there. McQueen seemed displeased with several aspects of The Blob, especially his salary because he made the short-sighted decision to take a smaller up-front payment rather than a cut of the profits. Yeaworth was surprised to learn that when McQueen died, the only thing found on his wall was a poster of The Blob. Surprising because he had disparaged the film because it was a B picture and he didn’t get paid what he could.

At first the movie was titled The Molten Meteor. They then changed it to The Glob, but that was taken. The next option was The Blob, which stuck. They wanted a title that people would make fun of, and they got free publicity from it.

Robert Fields – He played Tony, the apparent leader of the clique of boys that first encounters Steve.

He makes some interesting points about what he calls “Dying on Film.” He does not mean it as dark as it sounds, just that it is an expression that is used in acting fields. Actors see the aging process in their lives because they can see themselves at various points of their career. He compares this with a shoe salesman, who doesn’t see himself doing the same job at a younger age. Even though this is a dark point, he appreciates being able to see his younger, better looking self.

He shares a number of Steve McQueen stories, but they have a different angle than the rest since he was younger. He has vivid memories of riding in McQueen’s two-seater sports care, racing through winding roads at 100 mph. Robert thought of him like an older brother or a mentor of sorts. McQueen had a lot of charisma and impacted Fields’ life.

Blobabilia Wes Shank is an avid collector of memorabilia from The Blob. He has several still photos, posters, and the actual Blob that was used as a prop. The disc has a lengthy slideshow with the highlights of his collection.

Criterion Rating: 6.5

Fellini Satyricon, 1969, Federico Fellini

Over the last couple months, there have been an inordinate number of art films with graphic sex scenes. Most recently was Godard’s Every Man for Himself, and not long before that was Don’t Look Now with the infamous “love” scene. The crème de la crème were Salò and In the Realm of the Senses. I haven’t intentionally looked for explicit films. That’s just the way it has worked out recently. Fellini Satyricon is more in the category of the latter two, yet does not quite reach the same depths of perversion. It is a depiction of pre-Christian Roman times and does not hold back showing the debauchery and depravity, which results in a lot of sexual activity.

I first saw Satyricon ages ago. I honestly cannot remember whether I saw it on video or cable, although I’m pretty sure it was one of the two. I watched it expecting humorous scandal, and ended up wondering what in the world I was watching. I may not have even finished it. Since that viewing, I have obviously studied film, and maybe not so obviously studies history, including a lot of ancient history. I never read Petronius’ Satyricon, which the Fellini version was “freely adapted,” from, as they point out in the opening credits. I did read a few of the peripheral sources from that time, including some Tacitus. Today, compared with my younger days, I have a firmer grip on Roman history and culture. In these two respects, this viewing was far more informed.

I usually do not get into transfers when writing about these films. Part of that is because Criterion has the reputation of putting out the best transfers available. At times there will be controversy that needs to be addressed, like with Lola, but rarely do I feel it is important to point how good a transfer is. That changes with Fellini Satyricon because this 4k restoration and Blu-Ray display might as well be another character. It is hard to imagine this movie looking any better. Every second is a visual spectacle. Even if some scenes are difficult to watch or incomprehensible, they look amazing.

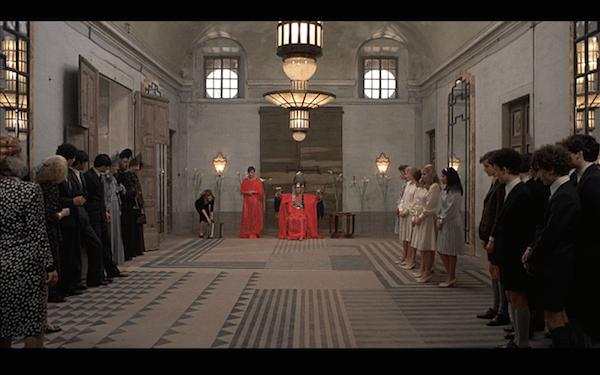

On the other hand, sometimes the clarity of the transfer reveals the façade. Examples of this are when they are on a large set that is intended to masquerade as the outdoors, with a matte painting in the background. The above screenshot of the Roman Baths is an example of how this type of scene looks glorious with the format, as the upper half is a painting. On their way to the Baths, the structure of the set is more visible and it looks artificial. That is not really a gripe because it probably looked more realistic on other formats, not to mention it came out in 1969 and looked far better than most anything else from the time period. I enjoy being able to see these “flaws” in the production, even if it reveals more behind the curtain.

To say that Fellini Satyricon is ostentatious and brazen would be an understatement. Every shot has a mind-bogglingly large set, with costumes so decorous that they look partly authentic and also like a freak show. We can tell that Fellini is in love with these little worlds he has created as much as we are, as he has extended tracking shots that reveal the entire set with carefully choreographed acting. The make-up and costumes are so brilliantly exorbitant that it is a festival of riches and completely immersive. It is a blast to be hypnotized by the visual marvels. Trimalchio’s Dinner is the most notable of these, even if the sets are intentionally less decorative than the brothels or art museum. They are the best portrayal of the hedonism and excess that these wealthy Romans indulge upon. At times they are disgusting, while at others they are wild and upbeat, such as the many energetic dancing sequences. They are always entertaining.

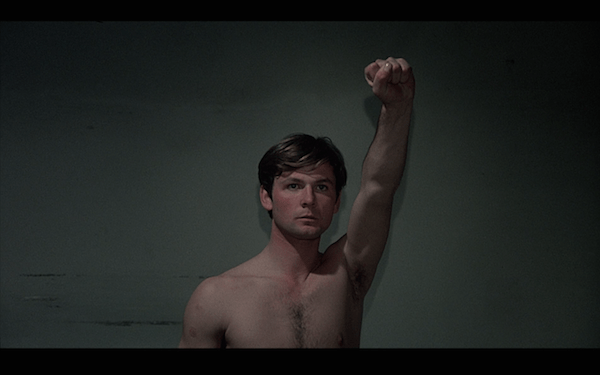

After viewing the spectacle, the plot seems less important, but it is worth touching on. Encolpio (Martin Potter) is the central figure and we see most everything from his point of view. He is involved with Ascilto (Hiram Keller), Gitone (Max Born) and Eumolpo (Salvo Randone). Their escapades begin at the heart of Roman culture in the city of Rome. They are later taken prisoner via boat to the outer provinces where Encolpio has to overcome a number of challenges, including fights with mercenaries, Minotaurs, and a merchant named Lichas with a lazy eye (Alain Cuny). While there is a beginning and ending, and the characters are on a journey of sorts, this is more of a slice of Roman life rather than a narrative with a central plot. In other words, you cannot compare this with the three-act Hollywood formula. It breaks virtually all the rules.

There is abundance of lascivious content. The three younger male characters have androgynous looks, and there are hints of homosexual activity even if they are not shown on screen until Encolpio meets Lichas, and that shows just a kiss. We are given the impression that a great deal of homosexual activity takes place behind the scenes. There is plenty of female nudity and heterosexual scenes, beginning with the brothel, and culminating in Encolpio’s sexual rendezvous with a tied-up nymphomaniac. I’ve already compared it to some later movies where graphic intercourse was shown, but it holds back from becoming anything resembling pornography.

Fellini took a great deal of license with adapting Petronius’ work, filling up much of the film with his own research and, frankly, his wild imagination. Despite his embellishments, it still stands up as being much closer to authentic compared to other Roman depictions. This is not the Rome from your ordinary Cecil B. DeMille epic or even an HBO miniseries. This was the underbelly of Rome from during Nero’s reign, which Petronius was a witness to, and Fellini translated for a modern audience. It is carnivalesque mostly because this 2000 year-old culture is so foreign and distant to the one in which we live in. The reality is there was quite a bit of debauchery in pre-Christian Rome. Fellini Satyricon is not going to stand up as a historical document, but it is a better representation than a casual viewer (including the younger me) might realize. It portrays animal sacrifices, the brutality and abuse of power, pagan worship, and wild, erotic celebration.

I cannot say enough about how visually splendid this film is. This post has a lot more screen shots than most, and I could have included even more. Every frame has something interesting to the eye, whether it is the flamboyant and eccentric character, the fantastic make-up, costumes, set designs, gorgeous landscapes and last but not least, the photography. The use of locations and color are not only unparalleled for the time, but they hold their own against some of the more artistic projects created today with modern technology. I will not spoil the beautiful final shot because it has to be seen, but it punctuates the film both visually and thematically. It is up there with the best shots in Fellini’s career.

My expectations for Fellini Satyricon could not have been lower. In fact, I wondered why it was getting the Criterion treatment at all. Instead, I fell in love with Fellini all over again. He was a genius and versatile filmmaker, and this is yet another dimension of his fine career.

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements

Commentary: This is a dramatic reading of Eileen Lanouette Hughe’s 1971 memoir On the Set of “Fellini Satyricon”: A Behind-the-Scenes Diary. This is a new type of commentary for me, and it is tough to keep up with while re-watching the movie. It usually does not correspond to what is on the screen, although it is usually relatively close. It also gives a wealth of information about every aspect of the production, so much that it’s impossible digest it all. I am listing a few tidbits that I found interesting.

- It came to be known as Fellinicon and was the most expensive of his films and the first with foreign financing.

- All 3 of the leads were young, unknown actors. Two were British and one was American. They represented hippie culture, which is a good fit for the Petronius’ style.

- There was a rival Satyricon in the works with a much lower budget. That is why this was named Fellini Satyricon. It was a way to distinguish between the two.

- Many of the sets and props had to be made quickly with short notice. A Venus statue was made overnight. Parts of the brothel set were built in a couple hours and shot in a way that makes them look larger. There are many other examples of this throughout the commentary.

- The Trimalchio dinner scene took three weeks to shoot. It was intended to show the residence as not being ornamented aside from the food, because Trimalchio was a poor landowner and former slave who worshipped food.

- The actor that played Trimalchio ran a restaurant that Fellini used to frequent until he started getting too fat. The actor was reluctant to appear in film and leave his restaurant alone.

- Fellini intended to capture the essence of a pre-Christian world, which he likened to capturing Martians. That is why this pagan world seems so foreign to us.

- The ship is designed with modern methods and is a bridge between the ancient and modern world. This was intentional.

- Petronius had Encolpio marrying a young girl, but Italian censors would not allow a marriage with a child. Instead he marries Lichas (Cuny), a male, but acceptable to censors.

- The suicide scene may have been a nod to Petronius, because he killed himself rather than be killed by Nero.

- The set was constantly crowded with four people writing books, a documentarian, photographers, and guests. It also required an enormously large cast and crew.

Ciao, Federico! – Hour-long documentary by Gideon Bachmann. It starts with Fellini directing a love scene, calling out orders as the camera tracks around a threesome. One of the great parts of him shooting without sound is you hear him talk loudly to the actors while the camera is rolling. They show many shots from behind the scenes, which they alternate with interviews and slices of life with Fellini. We see him totally in element, including him on a cussing diatribe railing against someone who is working on the production. We also see him angry, happy, content, serene, and focused. It was a good documentary, both intrusive and revealing, but they had a lot of access.

Fellini: A series of interviews. Fellini despised giving interviews, but he had trouble saying no. That was noted in Bachmann’s documentary as well. We’re lucky he said yes so often because he had a lot to say and was highly quotable.

Gideon Bachmann (audio), 1969 – 10 minutes. Starts with a good quote: “The ideal film is the one you are making.” Obstacles are stimulating, because they cause you to create. He calls Saytricon his most difficult film because he had to create a world and portray situations that are considered forbidden. It was a stressful film for him to make.

French Television, 1969 – This was a short interview of just over a minute. He talks about the morality, or lack thereof in Satyricon, and instead showed decadence and vitality.

Gene Shalit, 1975 – This was another short interview. It begins with a title card that reads “Perfection.” Shalit repeats a previous Fellini quote “A good picture has defects.” They have to be complete, vital, and cannot reach perfection. He makes fun of Shalit’s appearance because it is imperfect and outlandish, yet he likes him for those flaws. The same is truth with film.

Giuseppe Rotunno, Cinematographer: 2011 interview for the Criterion Collection where he discusses the challenges in filming this iconic film. They worked on a number of films together and became like school buddies. Fellini allowed a great deal of freedom, yet was precise as far as what he wanted. Rotunno set up lights for 360-degree views because Fellini also liked to be free and wanted to shoot from all angles. Fellini’s common question when discussing a shot: “But will it look real?”

Fellini and Petronius: New 2014 Criterion documentary with classicists Joanna Paul and Luca Canali. Tacitus describes Petronius as someone who played in the leisurely, seedy side of Roman culture. He was known as a scandalous figure. We are missing most of the books of the Satyricon today, with only having bits of three of them. Fellini makes the film fragmented to honor what we have of the original text. The book is very realistic, and the film contains elements of that realism. Trimalchio’s dinner is the only extended portion of the Petronius text that survives, yet Fellini exaggerates it. A lot of the content and characters come from Petronius, while others come from elsewhere, partly Fellini’s imagination and also other sources. Fellini does not reveal sources except for Horace and Ovid, because he was not trying to be academic, but he clearly did his research to prepare for the film.

Mary Ellen Mark: She was 28 when she was assigned the task of photographing production for Look magazine. This is a 2014 interview with her. She shot the sequences he did in the Roman Baths, which was a smaller set and then grew larger. She had total access, partly because people weren’t paranoid about leaks like they are now. She loved photographing Fellini. He was larger than life and seemed to enjoy being photographed. She called him a showman. He was so busy making the film that he was oblivious to being shot, but still allowed himself to be seen.

Felliniana: These are items from Don Young’s memorabilia collection. It is a series posters, books, programs, and so forth. It is interesting to see such various depictions of this highly visual film from different cultures.

This was quite a release. While the film cannot be considered a masterpiece, the amount of supporting materials that were created and used on this Criterion disc are staggering. With a heavy and detailed commentary, a terrific behind the scenes documentary, and several other odds and ends, this is one of the most complete releases I’ve seen in a long time.

Criterion Rating: 10/10

Every Man for Himself, Jean-Luc Godard, 1980

Back in my early days of cinephilia, I remember taking a survey film class. I had watched a couple of Godard titles by that point and was less than impressed. When we reached the French New Wave section and were asked to discuss Godard, I said, halfway embarrassed that “I kind of hate Godard.” The professor laughed hysterically. “Hating Godard,” he said, “is the first step in understanding Godard.” It is a typical reaction. Of all the New Wave filmmakers, Godard is among the least accessible, and that’s probably the way he wants it.

I have since changed my opinion of Godard, at least to a certain degree. Of course I realize that he is a highly accomplished and influential filmmaker. I have adored many films I’ve seen since, notably Band of Outsiders, Contempt, and Pierrot le Fou. Despite warming up to him, I still have not completely drank the Kool-Aid. I think he gets carried away on occasion with trying to be different, and many of his films are structurally unsound and more about having “cool” looking characters. Sometimes that contributes to his appeal, as those ingredients are found in my favorite films of his. Sometimes his work feels gimmicky and less substantive.

That opinion was based on 1960s Godard. Until now, I had yet to delve into his later filmography. Every Man for Himself is marketed as his “second first film,” yet it is unmistakably a Godard film and has many of the same attributes as his earlier work. In many films he gets carried away with using a filmic device, such as the jump cut in Breathless. In that case, it was jarring, yet influential. In the case of this resurgent work, the technique is slow motion. He uses it well, but there’s a reason why the jump cut is popular today while slow motion is relegated to sports clips.

What he does exceptionally well is still the case here. He is great at using sound and image. That begins with the opening shot of Paul Godard (Jacques Dutronc) sitting on a couch, framed by the hallway, while the sound of a loud opera singer is heard from an unexplained location. Later we discover it is a neighbor practicing his vocals.

His best use of sound and image is during the slow motion sequences. While the character’s actions will slow down, their dialog and the diegetic sounds are played at the normal pace. By using this method, sound jumps ahead of the image. It is never particularly revealing, but it is clever and creative, and makes many of the slow shots more interesting than they would be otherwise.

A distinct difference between this and earlier Godard is in how the characters are portrayed. I mentioned above that Godard likes to make his characters seem “cool.” This is far less true in Every Man For Himself. The men come off as despicable. The two female leads were played by exception actresses that would become major stars, Isabelle Huppert and Nathalie Baye, but they are portrayed as humble and downtrodden, but with a profound inner strength compared to the men. They may be victims of the men, but the powerful characterizations make them more relatable and sympathetic.

Godard has always enjoyed being jarring, and that is why young cinephiles like myself don’t always take to him. In Every Man to Himself he uses a new device, sexual perversion and nudity to unsettle the viewer. It is not entirely pornographic. Like Salò, the sexual situations are not erotic or titillating, but instead uncomfortable. Huppert plays a prostitute, and in one scene she is in the act with an older man. She is looking out the window, distracting herself from the sexual act by telling herself a story that we hear through voiceover. There is another scene where she is joined with another prostitute, who stands naked, casually facing the camera for several minutes.

The men are universally disgusting, either physically or mentally, and usually both. Paul is more interested in demeaning women than in finding a way to relate to them. He is a divorcee father, and is failing at a relationship with Denise (Nathalie Baye). The men that interact with Huppert’s character, also named Isabelle, are often preoccupied with monotony while using the women for sex. In the window scene, the man is on the phone conducting business. Men are self-important and care little for the women aside from the being objects of their indulgence. When they do interact with the women, it is often to insult or denigrate them, sometimes during a sexual act.

Even though the slow motion is used well from a technical standpoint, it does get tired and often fractures the narrative rather than enhances it. For instance, when Isabelle first meets Paul in a movie theater line, slow motion is used to highlight her reactions, but we lose an important character moment in the process. The best use of slow motion is when Paul attacks Denise, as shown in the cover image. He launches himself at her, flying across the air towards her shoulders and knocking her down. The camera slows down and as they roll around on the floor, the violence appears to transition to romance. We honestly cannot tell if they are fighting or engaging in an act of love, which sums up the ambiguous character relationship.

Every Man for Himself shows that Godard still has a confident handle on the camera and he has drawn some excellent characters, but the eccentricities of his direction are more on display and not as useful, unlike his better, earlier films. The grand sum is an intriguing piece of work with moments of brilliance, but overall stops short of being satisfying.

Film Rating: 5.5/10

Supplements:

Scénario de “Sauve qui peut (la vie)” This was the short film used to get financing for the feature. Godard had not written a script, so he used filmed the broad strokes of his ideas. He showed who he wanted to cast, what the character’s motivations would be, and how it would be filmed. The final product turned out to be mostly as he imagined, although Huppert and Dutronc were the only actors mentioned in the short that appeared in the film.

Sound, Image and Every Man For Himself: This is a critical video essay with Colin MacCabe. He gives much of the background details of Godard since his last major film, Weekend and how he faded into the background after the turmoil of 1968. Godard had been making experimental films, most of which were not watchable as movies.

Godard dislikes scripts because they remove the reality. He thinks they ignore the changing relation between “self and world.” He never used them for his films, which I think is one of the reasons why the narrative of some of his films seems improvised.

As for the use of slow motion, McCabe says, “slowed time down to let unseen realities appear.” The best example is the attack, which has the sound of glass breaking even if the unseen reality is the question between whether it is an action of romance or violence.

Godard on the Dick Cavett Show: These two episodes were shown back-to-back in October, 1980. Cavett may seem to be a strange choice to interview Godard. At times he seems out of his element with the filmmaker, but he was a good interviewer and makes both segments interesting

It felt like they had a better rapport during the first episode. They discuss the movie, which Godard is quick to refute as being a comeback. He claims he never left. He talks about how he sees the movie as a strong character piece. Cavett mentioned some poor reviews, which Godard thinks were most likely written by men. He thinks that men do not like the film because they try to identify with the male characters, and are disappointed to find them full of despair. The men are stagnant while the women are moving and growing.

At times Cavett and Godard seem to be on different wavelengths. Cavett asks Godard about how many people come out of his films having appreciated the work, but not enjoyed the film. This is much like my experience that I discussed in film class years ago. Godard thinks that people have to do a little work to get his work. They have a “responsibility in the making of movies,” and he weirdly compares it to eating hamburgers. Ultimately he is saying that people need to challenge themselves when approaching his films, and I agree.

The second episode is stilted. This could be partly because of Godard’s demeanor. He often takes pauses between answers, most likely to think about the way to craft an answer, but these take the form of awkward pauses during the interview. They talk about American movies, such as Hitchcock, and why Godard takes to them when they make such different films than he does. At times it seems like Cavett runs out of good questions. He starts asking about people, including Coppola, Truffaut, and in an odd back-and-forth, asks about another controversy involving Vanessa Redgrave. The interview falls off the rails, but Godard is still gracious and does what he can to stick with Cavett.