Category Archives: Criterions

The River, 1951, Jean Renoir

“The River had it’s own life, fishes and porpoise, turtles and birds, and people who were born and lived and died on it “ – Older Harriet

With The River, Jean Renoir is portraying two Indias. The native India is one of mystique and mystery to a westerner, but also one of serenity and a dedication to tradition. It is clear that he has fallen in love with that India (and he would later admit as much). The other India is the white upper class, post-colonial India, which Renoir may identify with as a westerner, but he seems to have mixed feelings about this India and portrays the characters as lost and confused.

Renoir uses documentary footage to show the real India and how the people live around the Ganges. In narration, we are told about “the animals and the people who lived and died near it.” We see people working on the boats; we see playing children descending stairs that reach into the river; we see people relaxing along the banks. The river is not only a place for sustenance, but it is also a place for escapism. The river is integral to the lives of the locals.

As for the English family that serves as the protagonists, they stay at arms length from the culture at which they are occupying, yet they are not disdainful. They respect and appreciate the traditions. The father prefers to walk through the bazaar on his way home and haggle over merchandise even though it is out of his way. The younger boy is fixated on snake charmers and wishes to learn their secrets. The English girls and Captain John are less attentive of their surroundings, and more concerned with their own distractions and affairs. They are “coming of age” in their own way while the river and the culture are relegated to the background.

The film has a great deal of voice-over narration, from Harriett, the English child protagonist, reflecting on her story of her first love presumably as an adult. It is her narration that we see both Indias, her insular version and the real one, yet she is educated and enamored by the true India and the magnetic lure of the river. This could mean that as part of her coming of age, she later came to an education and understanding of how special her surroundings really were, and how much the river influenced her life.

The primary white protagonists are Harriet, Valerie, and Captain John, and they form a sort of love triangle. Captain John has only one leg and is taking refuge in a foreign land as a way of escaping, a houseguest of their neighbor, Mr. John. He quickly befriends the family and the young girls. Harriet and Valerie both develop a crush on him, although they pursue it in different ways. Harriet is far too young for John, and hers is more of the fleeting girl crush. Valerie is older, who is not one of the family, but as an only child of a local businessman, she spends much of her days with Harriet’s family. She pursues John as a form of game, and she even toys with him and his affliction In one cruel scenario, she encourages John to play a game of catch and causes him to injure himself. Whether or not her heart is really into the affair is up in the air, but there is no doubt about Harriet. She is enamored by the visitor.

The white family has Indian connections. Dr. John has a mixed race daughter, Melanie, from a deceased Indian wife. Melanie serves as the mechanism for introducing Indian culture into the film, including a lovely fairy-tale diversion into the background of the God Krishna. Melanie also represents the contrast of both cultures. She has an English-centric upbringing, but as she gets older, she embraces her native culture. She even insists on wearing a Sari permanently. Bogey, Harriet’s younger brother, has a young Indian friend who encourages his foray into Indian culture and will be present for a later, game-changing scene.

These younger characters are all lost in a foreign land. In this way Renoir seems to be contrasting the privileged white class against the comfortable locals. Harriet is lost in love, which is a fruitless pursuit given the age difference. Valerie is lost in herself, and is more capricious as a teenage, only child, yet that does not seem to be an aspect of her person that she is proud of. Captain John is completely lost. He is coming to terms with his loss of a leg and being less of a man after the war, and has wandered from place to place, unsuccessfully trying to find somewhere he belongs. The least lost is Melanie, although based on her multi-cultural upbringing, she could have been portrayed as being the most confused. Even though in one sequence, she says to her father “someday I shall find out where I belong,” but she appears to have found it. She is resolute in embracing her native culture, while still embracing the love for her father and friendship with Captain John. Even though she is not squarely placed within the love triangle, it seems most appropriate that she end up with the visitor.

The heart of the movie is when the Indian traditions are shown. Here Renoir slows down the pacing and backs away from the narrative. It shows the real India, while also fragmenting the movie. The foolish meanderings of the young girls and their rivaling affections for Captain John seem to be insignificant compared to the beauty of the culture around them, which has been around for thousands of years compared to the teenage years of Harriet and Valerie. The previously mentioned Krishna story and the Hindu Festival with 100,000 lamps are when the film is the most pleasant, relaxing, and the most beautiful. Even though the coming of age stories are interesting, they pale compared to the story of the real India that Renoir puts so much care and love into showing us.

It is worth mentioning that Satyajit Ray and Subatra Mitra worked as Assistant Directors on the film. They were undoubtedly influenced by the work, and even though their later work would be unquestionably Indian, you can see some of the pacing and the mixture of documentary footage with narrative in their narrative films. I can see a lot of similarities between The River and The Apu Trilogy. The Renoir film is worth praise in its own right, but it also deserves credit for influencing the career of the man who would be called “The Father of Indian Cinema.”

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements

Jean Renoir Introduction:

The idea came to him when he was reading book reviews. He saw a glowing review of a book about India. He read the book and was convinced. All of the studios rejected him, thinking that a movie in India required tigers, Bengal lancers, or elephants. He then met an Indian florist that wanted to get into film. It was difficult at the time because Europeans and Americans did not understand Indian issues, so they had to film India through English eyes.

He heard about Rumer Godden, who was English but was born and lived in India. Renoir acquired the option before they met. They flew to India to make sure it was acceptable to shoot there, and Renoir was bowled over. He loved the country.

Martin Scorsese: 2004 Interview.

He went to movies with his father during his childhood and he describes this as one of “the most formative” experiences he had, and he compares it to The Red Shoes as the two best classic films in color. It was the first Renoir in color and the first Indian film in color.

India had a terrific canvas for color primarily because of the vegetation on the bank of the river. Many of the scenes he thought were reminiscent of a watercolor painting by Renoir’s father. Renoir apparently took a long time to arrange shots in a certain way, so possibly that was because of his father’s visual style.

Around the River: 2008 documentary about The River by Arnaud Mandagaran.

In a 1958 biography, Renoir called The River the favorite of his films. After Rules of the Game failed, he left France, made six films in the USA and then RKO dropped him after the failure of The Woman on the Beach. He left for India in 1949.

Kenneth McEldowney, producer, talks about his experience behind the film. He was first looking at one book, then that author recommended The River. He found that Renoir had the rights although he was not going to do anything with them. Renoir’s only condition was that he get a paid trip to India to make sure he wanted to shoot there, and he fell in love. Rumer Godden had also written Black Narcissus, and hated that it was shot entirely in a studio. She wanted Renoir to shoot in India.

Satyajit Ray worked up courage to ask for Renoir at hotel reception desk. He told the famous director that he was a great admirer of his, and Renoir was very nice. Ray “pestered him with questions, but he was very patient.” Asked him about French films, his father, and just about everything he could think of. Ray told him that he would like to make a film and described Pather Panchali.

Alain Renoir – His father had problems with the screenwriters. They would write something, and then he would film something completely different. Most became infuriated with him. Rumer Godden was the exception because she knew the country and the culture. This was one of the few occasions that Renoir and the writer collaborated well.

As for the Indian elements, they were unquestionably Renoir. He saw Rahda dance and wanted to meet her. The role of the mixed race Indian was not in the book, but was invented to bring more of India into the film and cast Rahda as Melanie. They found from the previews that Captain John was not sympathetic and the children acting was not as strong, so they over-emphasized the cultural moments and river sequences, which I think turned out to be a good move.

Jean Renoir: A Passage Through India: 2014 Criterion visual essay.

Water was a metaphor for life in Renoir’s work, and this was quite a good fit for him. He had been criticized for not returning to France after the war, but after The River, Renoir considered himself beyond nationalism.

The River was always his favorite because it finally made him an international director.

At one ceremony for Ray, it was said that Ray owed everything to Renoir. The elder director scoffed and said he owed nothing to him, and that he was the father of Indian cinema. Ray’s reaction was not recorded, but he later named Renoir as one of his major influences.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Redes, 1936, Emilio Gómez Muriel & Fred Zinnemann

Sergei Eisenstein famously visited Mexico in 1930 to attempt a film project, ¡Que viva México! which fell through for a number of reasons. Despite his failure, he left an indelible mark on the film industry. Initiated by a strong left wing state, the film Redes was produced in the vein of Eisenstein. While it is unquestionably a work of propaganda, it resembles the Soviet montage, highlighting the strength and solidarity of the workers while using editing techniques to portray the upper classes in a poor light.

The film is set in a small fishing village and begins with tragedy. Miro’s young boy passes away because there was not enough work for him to feed him the child. We see a number of sullen and somber expressions from Miro as he deals with this loss, while a boiling anger towards the system lies close to the surface.

The economic environment changes when the workers discover a bounty of fish, so many that there is enough work for everyone. The capitalist Don Anselmo makes sure to capitalize, and instructs his henchman to harvest as much as he can. “I just need people, boss,” he replies, establishing the reliance of labor in order for the prosperity to continue.

Miro works because he needs the money, but the memory of his child is not lost on him. He regrets that the work came too late. He along with others set forth into the water, and we see every stage of the process of fishing. Just like with Eisenstein, the film language celebrates the workers and shows their passion and ability. There are many shots that show the collaboration and cooperation it requires to mine these vast quantities of fish. The camera pauses on a muscular man pulling in the boats with the fish, highlighting the muscles that it requires. It is a well-done visual sequence that is shot documentary style and reminded me of Flaherty’s Man of Oran.

When the men are talking, one asks: “Who’s more stupid? Man or fish?” One response is a joke about women, but within the context of the movie, the question is valid. The men, at least the poor workers, are soon being exploited. When they return to the bosses with their massive fish haul, they are disappointed by the payment they are given. If this is the best they will get, then they will not be able to feed their families. They know the value of the fish, and some immediately figure out that they are being exploited to line the pockets of the rich.

One of the bosses reassures him that if they vote for him, he will clean everything up. Miro rejects him, knowing that he’ll say anything to get votes. “You know the big fish always win,” they say. From there, they decide to band together and unionize.

Even though the third act of the film is predictable, I’ll stop there. The last act is somewhat of a mixture between Salt of the Earth and an early Eisenstein movie. They use montage theory effectively. There is one scene where a significant incident takes place, which is followed by successive, quick cuts to stills of symbols, including currency, fish, and work, reinforcing the message that the workers needs to consolidate in order for their power to be felt.

The acting may not be spectacular, although the plot and message did not require them to emote. Just like, say, Alexander Nevsky, the ‘good guys’ acted and were portrayed as dignified, while the ‘bad guys’ were portrayed as greedy pigs.

Just like with the Russian and Flaherty films that I’ve already referenced, the strengths were in the visuals. Paul Strand, a noted photographer, did a fantastic job at getting the most of the location shots, where Muriel and Zinneman choreographed the action with precision. The film’s visuals and location shooting look ahead of its time, especially for an international film.

Film Rating: 7.5/10

Supplements

Martin Scorsese Introduction:

This was a short introduction for a film that Scorsese had never seen before the project began. It had three fantastic, and it was a state sponsored and a progressive, leftist film. Paul Strand was a visual artist; Fred Zimmerman had worked with Robert Flaherty (and I noticed some similiarities in shooting style), and Emilio Gomez was comfortable working in the Mexican system.

Visual Essay on Redes: Kent Jones, 2013.

Redes was conceived Mexican and shot at fishing village of Alvarado. It was financed by the Ministry of Education and Carlos Chavez. It was conceived as a rigorous Marxist analysis of modern living.

There were conflicts between Paul Strand and Fred Zinneman. Strand wanted still images and was reluctant to shoot anything moving, but of course Zinneman wanted there to be some action. The result is somewhere in between.

Reviews were favorable, but the movie was not widely seen. The negative was subsequently lost. Zinneman said that the Nazi’s burned it, but that has not been substantiated. The WCF took it over in 2008.

Vernon, Florida, 1981, Errol Morris

I live in the southeast, so I’m used to southern culture. We have our share of “rednecks,” but aside from the accents and political leanings, much of the local flavor isn’t too different from any other medium-sized city. Because it is nearby, we visit Florida somewhat frequently as a getaway. It is often dubbed the “Redneck Riviera.” Sure, you get a lot of transplants, tourists, and there’s a large Latin American and Cuban population, but there are also plenty of homegrown locals. On every trip, we’ll encounter some weird local. Generally, the further south we go, it becomes less “redneck” and more multi-cultural.

The panhandle is a different breed entirely. I’ve only been there a handful of times, and it has more in common with Alabama and Mississippi than Tampa and Miami. Vernon, Florida, is just like any southern town out in the middle of nowhere. Having been to many of those, I can testify that there are some unique, backwoods characters, and many of them are not among the intellectual elite (although I do know some highly intelligent people living in small southern towns). Morris chose Vernon by accident, but many of the same type of people could be found in almost any southern town of the same size.

While Gates of Heaven had a narrative arc, it also had quirky and unique characters with stories to tell. Vernon, Florida sheds the narrative and focuses instead on the colorful characters in this small Florida panhandle town. To call the characters quirky is an understatement. They are sheltered, naïve, and passionate about their worldview, but it is far from metropolitan. The subjects that Morris interviews are far from the most intelligent bunch, and Morris seems to go out of his way to portray their ignorance. While at times these characters are humorous, at others their simple nuggets of wisdom are endearing.

“You ever seen a man’s brains?” asks one of the residents, randomly, and then goes into how they are contained within four bowls around the circumference of the skull (aside from “bowls,” these are my words, not his). “You are not a one track mind. You are a four track mind,” he says, and then he goes on to explain the thesis. Like many of the interviews, at first the reaction is ‘WTF?’ and as the diatribe continues, it keeps on getting more absurd. That’s the essence of Vernon, Florida. It is a lot of people saying strange, kooky, and dumb things.

Even Ray Cotton, the preacher, is not immune to being taken to task. He is developed as a nice, honest guy, who decided to spread the word of the Lord for less money rather than take up a more lucrative profession. However, when he preaches, he is yet another source of humor. He begins by talking about the word “therefore,” and how Paul uses it quite a bit. He had to look up the definition of the word in Webster’s dictionary, and finds that it is a conjunction. He then has to look up “conjunction,” and that leads to him looking up other words. He does come around to a point, but he takes an extensive journey through the world of Webster in order to get there.

One of my criticisms, which is more of a minor quibble, is that Morris spends too much time with turkey hunter Henry Shipes and his friends. Henry has his quirks, such as when he gives a contradictory statement about whether to go after turkeys when there’s a hen present. He also has some more cinematic moments, such as when they go out on the boat to try to find a nest of turkeys. Compared to the remaining characters, he is the least interesting, and he does not say much for the town other than the fact that people hunt wild turkeys.

There are plenty of other motley characters and they all share their own bit of warped wisdom. One of the most memorable quotes for me was a guy talking about Wigglers, who says, “I never studied no books about these wigglers. What I know ‘bout ‘em is just self experience. Uh, they’ve got books on ‘em. Them books is wrong.” There’s also a police officer, who frankly seems bored. There’s a guy who is boggled by the concept of jewelry, and another who pontificates on random things happening.

Errol Morris is, of course, an intelligent and well-educated individual. While he can be seen as exploiting these people for their simplicity, the joke is occasionally on him. In one scene, he interviews a couple about how they brought some sand back from vacation and put it in a jar. Over the years, the sand subsequently grew. “In a couple of years that jar will be full,” the man says. What? Sand doesn’t grow, so this initially looks to be another example of their Vernon stupidity. Morris found out later that there are certain types of sand that can absorb moisture and will gain in size, especially when moved to a different climate. There is another scene where a man calls a turtle a “gopher,” and initially we again think he is confused or just stupid. What’s not mentioned is that there is such a thing as a Gopher Tortoise. In his defense, Morris possibly knew about the tortoise and this may have just been a random comment that people picked up on. Despite the gopher comment, the gentleman’s speech about turtles is quite entertaining.

While it is enjoyable to meet these characters and hear their words of wisdom, as I noted, there is not a point of narrative. The film meanders and is basically a portrait of a small town with quaint, folksy people, who seem foreign to the art-house cinephiles who would see an Errol Morris documentary. It is an enjoyable way to spend an hour, but it does not compare with some of his best work.

Film Rating: 5.5/10

Supplements

Errol Morris: Interview from 2014.

Morris talks about the genesis of this project. At first he intended to film a documentary called “Nub City.” This was an area in Florida where they had the highest rate of insurance fraud, most of which were from people who blew off an arm or a leg in order to collect the insurance money – hence the “Nub” part of the nickname.

He was warned that “Nub City” at night because it was too dangerous. At first Morris found it not too dangerous, but fabulously weird. He interviewed some insurance fraudsters and for the first time in his life, he got beat up. In hindsight, “it was sort of unpleasant,” he says.

The real “Nub City” is Vernon, FL. Rather than risk life and limb, he instead just started talking to the locals and he found the characters engaging. This explains why the film lacks a subject, thesis or narrative. As Morris puts it: “I just love these guys. So I made this movie.”

This is the second film in the disc with Gates of Heaven, so the rating below is for both discs combined. Gates of Heaven is both the better film and has the better extras, especially because of the Les Blank documentary. While Vernon, Florida does not measure up, it is basically a second movie for the same price.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

Gates of Heaven, 1978, Errol Morris

Early on in Gates of Heaven, one of the interview subjects gives a quote that summarizes much of the film: “The love that people have for their pets is tremendous, something that is very, very difficult to explain.” As a pet owner for most of my life, I identify with this statement. When each pet has passed, it has been a difficult period –- almost to the level of losing a family member. For some people, losing a pet is worse than losing a family member.

At a recent film festival, we saw a short film about Cherry Pop, a Fort Lauderdale show cat with wealthy owners that lived during the 1980s. Her “parents” would buy her jewels, gave her a Rolls Royce, and spoiled her to high heaven. It was estimated that they spent $1 million on this cat. It was a neat little film with archived video footage from home movies, and I can think of fewer examples of someone loving a pet as much as this family. It was ridiculous that they spent all that money, but the feeling in their hearts was genuine. When they lost Cherry Pop, they were devastated.

The opposite is also true. There are many who see animals as packages of flesh with no real purpose. Since they are not human beings, they do not deserve to be memorialized or even treated humanely. These are the types who would raise no objection about rendering a deceased pet’s remains into a raw material.

Gates of Heaven is about this dichotomy. It explores the levels of which people love and care for their pets, in this world or the next, and those who think of them as garbage that needs to be processed somewhere. It is also about more than just the pets, but how people can turn these emotional connections into business enterprises, and whether they do so out of compassion or in order to line their own pockets.

The film begins with Floyd (or “Mac” as he goes by) talking about losing his Collie to an accident. Devastated, he wanted to find a piece of land to bury the remains of his loved one. When he found the land, he had a dream and eventually it led to the creation of a pet cemetery.

Mac is a man of compassion and his business interest is more about his love and respect for the deceased animals and the families who mourn them. He lambasts the rendering companies who have no respect for the deceased. There is another interviewee who talks about people being upset when a zoo animal’s remains went to rendering company. He admits that they lied and said that they buried them.

Mac realizes that there are more economic ways to maintain a pet cemetery, but he claims that his is “not a fast buck business.” He could have efficiently dumped a number of animals into the same burial plot and that would have likely brought him more profits, but it went against his moral code. Unfortunately, because he focused too little on the business aspect, he lost his shirt and his buried pets were forcefully evicted from the cemetery.

Mac when talking about the failings of his business and any culpability: “The only thing I’m guilty of is compassion. And that’s all.”

These pets were transferred to Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park. Contrary to Mac’s endeavor, Bubbling Well is a successful pet cemetery because it is built upon solid business practices.

While the father and two suns that run Bubbling Well see it more as a business, does that mean it is exploitative? That is up to the viewer’s interpretation. There is one scene where a couple are putting to rest their loved dog Caesar. They are memorializing him with the patriarch of the business, Cal Harberts. He asks to see a picture of Caesar and compliments the dog for having such a gorgeous coat. He then talks about what great pets mixed breeds make. His tone is respectful and it comforts the mourning couple, but you have to wonder whether it is genuine. It could be superficial and a variation of what he says to every client, or he could have been playing to the cameras. Mac would share similar words, but we can imagine that he may emotionally empathize more with his clients.

Harberts leaves the operating of the business to his two kids, Phil and Dan. Dan dresses in 1970s, post-hippie fashion, and aspires to be a rock star. He admits that he partied during college, yet feels that he learned things and gives an odd explanation as to why, which shows that he basically did not learn. His brother Phil is his opposite. He has experience in the insurance industry and has good business sense. He compliments himself on his great memory and how it is necessary for the business that he uses it to keep up with all his veterinarian contacts. When he speaks, he is all either business or affirmation. He wants to even expand the business, and when talking about his father’s success, “he read the same textbooks as me.”

Phil is creative. He builds a “Garden of Honor,” which is a resting place for service dogs, whether they are police or seeing eye dogs, and they are buried for no price. Other owners can bury their pets in the same section, but at a higher price because of the prestigious land.

Bubbling Well still exists today. Here is a recent article the facility and its history.

Dan is neither Phil, Cal or Mac, and his appearance towards the end gives this documentary an extra quirk (although it has plenty, mostly from interviews of pet owners). He really is a slacker. We see him in his apartment listening to psychedelic music, presumably his own. He writes songs and longs to have them heard, but realizes that as time passes, that dream is fading.

The interviews with pet owners and snapshots of their interactions, like the memorable singing owner and dog, offer little to the narrative, but they are what gives the documentary its flavor. They recall the statement I began this write-up with, that people inexplicably love their pets. One lady says that she wants her pet buried because she believes they will be together again. In a sentiment that Mac would agree with, Mrs. Harberts says that the “at the Gates of Heaven, an all compassionate God is not going to say ‘Well, you’re walking in on two legs, you can go in. You’re walking in on four legs, we can’t take you.”

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements

Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, 1980, Les Blank

The bet was that Morris would not be able to complete Gates of Heaven or Werner Herzog would eat his shoe. This documentary is Herzog living up to his end of the bargain, with help from friends such as culinary goddess, Alice Waters, and of course the documentarian, Les Blank.

The documentary is in typical Les Blank style. It begins with upbeat music, photography that focuses on a weird object (Herzog’s walking shoe), and of course food.

After preparing the shoe Cajun style, and boiling it for 5 hours, he proclaims the shoe edible. Herzog says that he has survived Kentucky Fried Chicken so he can handle this. Does he eat the shoe? Sort of. They cleverly intercut the famous Chaplin shoe-eating scene from The Gold Rush. He does eat the shoe, but not the sole, comparing it to the bones of a chicken.

Back to the topic of this post. Herzog is proud of Morris for making the film. While eating the shoe is foolish, he is proud that it was a motivator.

Film Rating: 8/10

Herzog at Telluride: “You can make films with your guts alone.” This is a very short clip where he complements Gates of Heaven as a very fine film that was made with no money and only guts.

Errol Morris: October, 2014 interview.

Just like with The Thin Blue Line, Errol Morris proves to be an excellent interview subject.

He tells a funny story about how Douglas Sirk, a director that he respected tremendously, walked out of his movie. “This isn’t a movie. This is a slideshow.” And then he said, “There’s a danger that this film could be perceived as ironic.” What?

Morris doesn’t remember Herzog saying he would eat his shoe, and minimized the influence of that “bet.” He claims he was more inspired by Herzog’s films.

Wim Wenders saw a very rough cut, one that they were worried wouldn’t fit into the projector. He said it was a masterpiece. That was the first positive review. It was very encouraging of course. Siskel and Ebert followed suit and loved it. They were known to fight with each other, but in the case of Morris’ film, they fought about how good it was. They reviewed it three times and put it on best of year list. “Thank you, Roger. Thank you, Gene.”

This is a two-film disc with Vernon, FL, which will be discussed next.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle, 1973, Peter Yates

The Story of Eddie Coyle is a rough edged movie with stern and serious characters that are either acting out of desperation or opportunism, all the while taking advantage of everyone that gets in their way. Everyone has an agenda, and much of the movie is them taking slight steps to manipulate the situation to reach that agenda.

If there’s any doubt about how rough the movie is, it is quashed early when Robert Mitchum’s Eddie Coyle tells a story about putting his hand in a drawer so that nuns would smash his fingers. He has lived a tough life and circumstances have turned against him to where he’s looking at facing time. Meanwhile his “friends” are either running guns for him or robbing banks.

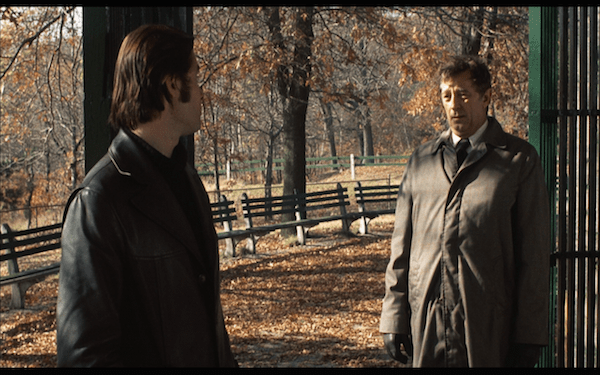

One thing that jumped out at me is the correlations between the uses of space. There are a few tense action sequences, but the remainder of the movie basically consists of people talking to each other at different locations. A great deal of it takes place in the outdoors in the stark daylight, with contrasts with the darkness within each character.

The colors are often vivid pastels, which are used effectively as a way to color the cars for each character. Even on an indoor set like the bowling alley, the bright colors give some vibrancy to what would otherwise be a dark location. They use a variety of locations for these conversations, such as near a riverbank, at a park, in the parking lot of a grocery store or train station, and various other locations. For all the underhanded activity, the template is bright and might otherwise be seen as cheery, but the characterizations and acting keep the film gritty.

Again, using spaces, they differentiate between public and private space. They show Mitchum disheveled at his home. This is a rare glimpse of his private life, but other than him having his shirt un-tucked, it isn’t altogether different that the public spaces we see. It is still brightly lit and he barely cracks a smile, even to his wife who he ushers out while he makes important phone calls.

There are a lot of dialogue scenes with people talking in restaurants, often with Coyle and Jackie Brown (Steven Keats) talking about setting up deals. The diner scene above is a rarity in that it takes place at night, but it still has the same bright lighting, and even adds color with the bright yellow menu reflected on the mirror. It almost appears to be an artificial sun that is hovering above them.

The outdoor night scenes are barely lit, showing emptiness and desolation. There are often long shots with cars driving at night where the only light source is the headlights. This emptiness correlates to the character’s struggles. Many of them are left out to try and are truly alone. They have no real “friends,” especially not Eddie Coyle despite the title. The stark night scenes are not used often and only in important, key situations (like the screenshot above that I will not spoil).

What separates The Friends of Eddie Coyle from many “heist” (if you can call it that) films is the pacing of the “action.” The scenes play out naturally and slowly. This begins with the bank robbery, with many quick cuts to show reactions, slight movements, and the mechanics of the scene. As the pace continues, an unsettling uncertainty sinks in. The slightest movement could make the whole thing go awry, and the viewers are essentially preparing themselves for something to happen. The same sort of pacing is used for the gun exchanges. There’s more action in these scenes, so there is a lot more cutting back and forth, occasionally broken up by characters interacting, and then cutting again as people move into position. Sometimes something climatic happens, while other times nothing happens. It keeps the viewers on their toes. These scenes are wonderfully composed and edited.

Here is where I’ll dip into spoiler territory, so if you have not seen this, you might want to check out now.

The title is meant to be ironic. Eddie Coyle has no friends. Dillon is the guy who seems to be his closest friend and confidant during the movie turns out to have the same motivation as Coyle and double crosses him. Coyle double crosses his other friends, beginning with Jackie Brown, and then he offers up the bank robbers as well – anything that will get him out of hot water. The cops, like Dave Foley, sometimes seem to be looking out for their subject’s best interests, but they are merely playing them. Despite the sacrifice that Coyle makes, it isn’t enough to get him his relief. Dillon makes a greater sacrifice and appears to get his relief, but we will never really know.

Often I try to read deeper into films like this to see what they say about society. The core of The Friends of Eddie Coyle is distrust. Everybody is out for themselves and you cannot trust them, whether you’re in a diner or at a hockey game. Could this be a statement on the Vietnam war that was going on at the time? Could it be related to the Watergate scandal that had just occurred (although to be fair, I’m not sure if that was resolved during the movie)? In this instance, I think there are no deep messages about early 1970s society. It is merely a slick, well-done and somewhat unique crime film, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Film Rating: 7.5

Supplements

Commentary: 2009, Director Peter Yates.

He considers it among his three favorite films that he directed along with The Dresser and Breaking Away.

Yates talks quite a lot about the actors, which is not uncommon with Director commentaries. One of my pet peeves is that they rarely say anything negative. It’s not that I want them to dish on their stars, but I think there could be more substance to a commentary than just gushing about actors. Nonetheless, it was interesting to hear him talk about his cast, especially Mitchum.

Mitchum was the type of guy who didn’t like to discuss his performance in advance, but listens when shooting. He would then adapt accordingly. He wanted to conceive his own ideas first and go from there. Yates said that he was the consummate professional and very impressive. He worked on his Boston accent, and concentrated on holding himself steady to capture the downbeat aura of Coyle.

He said that Boston was very cooperative, letting them shoot in public places and shutting traffic down. Since there were so many public spots, this really made the film.

He considers the film to be the opposite of The Godfather. It was not glamorous or romantic, nor was it about mobsters. It was about morally bankrupt common criminals just scraping along.

This disc is particularly light on features for an upgrade. Other than the commentary, there are image stills. Those are nice, but not as substantial. I would have liked to have seen interviews or a visual essay. Still, because of the quality of the film and the transfer, it is a worthwhile addition.

Criterion Rating: 5.5

On the Waterfront, 1954, Elia Kazan

Waterfront Week was quite an experiment. This is not something I’ve done before but I’ll most likely do it again for important films as they come along.

Here are the posts from the week:

Kazan Naming Names – This is about Elia Kazan’s experiences with the HUAC and how the film is partly autobiographical.

The Great Performances – The film had arguably the best ensemble, and many (including me) would say had the greatest performance of all time. This piece talks about all of the major actors.

My Favorite Classic Movie – After a week of analysis, this is my summary as to whether this stands up as one of the greats of classic cinema.

Film Rating: 10/10

Supplements

Commentary: This is one of the rare occasions where I did not listen to the commentary for this release. The reason? I’ve already heard it. This is the same one from the older DVD. Of course it has probably been 15-20 years since I heard Richard Schickel and Jeff Young talking about the movie. I remember good things and it most likely enhanced my appreciation.

Martin Scorsese and Kent Jones: 2012 interview with the pair who had together made the documentary A Letter to Elia.

Scorsese had a connection with this period of American cinema because it reflected the world in which he lived and grew up. Other movies were still just generally correct. On the Waterfront and Kazan films captured the realism.

They talk about the how the performances moved them and, of course, the HUAC. The part that relates to Kazan’s testimony is the least convincing to Scorsese. He was not aware of the political situation when he first saw it, although he knew the paranoia and controversy from growing up during the time.

Elia Kazan: An Outsider: 1982 documentary directed by Annie Tresgot.

This documentary has Kazan primarily telling his own story. It starts with a house in CT that he acquired in 1939 through his acting. He then got another role, another piece of property, and became a director. He joked that his Greek background had taught him to buy land for security, and once he had that, he could take risks.

He talks about his origins in theater with the Strasberg school, calling it essentially human, rooted in psychoanalysis where people train themselves to be in control of their emotions. Objects are essential.

He reflects on his life as a Communist and the HUAC. He recalls the specifics of how he was voted out of the party (22-2). Afterward he had still been enamored with Soviet Union until the truth of what they had been doing came out, especially the German pact.

He says he was not pressured to testify, but instead had conviction. Solzhenitsyn’s and Kruschev’s books had a major effect on him. The experience changed his life and toughened him. Even though he was in pain from the alienation, his films got better after he testified.

”I’m Standin’ Over Here Now”: 2012 Criterion documentary that has interviews with a number of Kazan scholars and film historians.

He began his theater career with Thornton Wilder’s “The Skin of My Teeth,” yet later directed Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams. One difference between he and other theater directors is that he would engage with the playwright’s on the creation of the play.

The first draft of anything resembling Waterfront was Arthur Miller’s “The Hook” about gangsters in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The studios got cold feet because of Miller’s communism. Miller left project.

Boris Kaufman was chosen as cinematographer. He had worked with Jean Vigo and others, and was chosen because they wanted images of realism. Kaufman and Kazan had a great rapport and cohesion with each other.

As for the allegory of the HUAC controversy and Kazan’s testimony, most people at the time did not make the connection. They say most people today do not make the connection because the time is past (Of course I disagree). Kazan said belligerently that it was about his testimony because he was proud. Budd Schulberg, the screenwriter, argued that it had nothing to do with either testimony, that it was based on a true story.

Eva Marie Saint: 2012 Criterion Interview.

Her routine during the film was that of a housewife. She would go home, make dinner, go to work, come back home, etc. Previously to the film, she and Brando had done improvisations before, but had not acted together before. She was shy about doing the love scene while wearing a slip on camera, but Brando took her aside and whispered “Jeff” – her husband’s name. It worked and she was relaxed.

Elia Kazan: 2001 Interview with Richard Schickel.

Kazan humbly calls it a wonderful screenplay with a wonderful actor, and that’s why it worked. It was a great experience for him and the closest he came to making a film exactly as he wanted.

He talks about the cab scene and how it has become so popular. He takes no credit. All he did was take the two characters in the backseat of a barely assembled set. They knew the characters and they made the scene.

Thomas Hanley 2012 Criterion interview with child actor from the pigeons. His story was interesting because he retired from acting and became a longshoreman. He was the real deal.

His father was killed and was no saint, but he was never sure why. During the emotional scene, Kazan irked him by suggesting his father was killed for squealing. This was before he did the “pigeon for a pigeon” scene, otherwise he would have tried to portray his character with more toughness.

His career choice was to go on the waterfront or enter a life of crime. He forged his documents, got his coast guard pass, and passed through the waterfront boards.

The reality on the docks were as portrayed in the movie. People didn’t squeal. People got killed. Mobster activity existed, but eventually they would rat on each other. Because of this double standard, now Hanley has no qualms with informing to police.

Who is Mr. Big? 2012 Criterion interview with James T. Fisher, author of On the Irish Waterfront, about the historical basis for the film.

Irish immigrants that came over in the 1820-30s had limited opportunities. Many worked on the docks out of necessity because of danger and it wasn’t a job in demand. They made it their own and achieved political power. Bill McKormick and his family controlled all the ports by early 20th century. McCormick came to be known as “Mr. Big.” People were taken care of as long as they accepted the system, which was not beneficial to them. They had low wages, danger, just as it was portrayed in the movie.

Father Phil Carey tried to achieve social justice for these employees. He received intimidating calls immediately and was warned to stay away. He was even intimidated by the monsignor.

John Corridan was an assistant to Carey who held similar convictions. He spent two years studying the waterfront. He understood the system, bosses, etc. There was a journalist at that time named Malcolm Johnson doing some investigative reporting. Corridan spilled everything to the journalist and blew up the waterfront. Johnson won the Pulitzer and Corridan became a celebrity.

Contender: Mastering the Method: 2001 documentary about the famous scene.

Rod Steiger, James Lipton and others were interviewed.

They really had a makeshift set, which half a taxi, a steering wheel and a seat for a driver. This was a way of cost-cutting. Brando was upset because there was no rear projection, so the instead used blinds because they had seen that in other taxis.

There were three shots. One was straight on both actors together, and then they shot from each actor’s perspective. Brando left for an analyst appointment while Steiger was shooting his part. This bothered Steiger and he wanted to prove himself. That’s part of the reason why he feels he brought such a goof performance.

Strangely enough, Brando did not think he was good in the film. Although a brilliant actor, personally the man was an enigma.

Leonard Bernstein’s Score: 2012 video essay for Criterion featuring Jon Burlingame.

They wanted Bernstein for his star power, not for what he could bring to the movie. He had never scored a film before.

It was rare for the time to start with a single instrument, which was a lone French horn with a few other quiet instruments gradually joining in. Bernstein called it “a quiet representation of the element of tragic mobility that underlies the surface of the main character.”

He composed numerous themes, including ones for Terry Malloy, violent scenes, and the love (or “glove”) scene. He also was able to add music for the cab scene, which was initially going to be played without music. Bernstein’s score begins when gun is pushed away. It is similar to the earlier, sad dirge used at the cargo scene.

Was there too much music? Schulberg said that at times it seemed loud, but he loved the score. The critics loved the score as well, although it lost to The High and Mighty, possibly because Bernstein was not part of the Hollywood industry. The music for On the Waterfront is remembered now far more than any of the nominees.

On the Aspect Ratio: Initially it was projected at 1:85. This was during the origins of the transformation from 1:33, so camera operators framed for both aspect ratios as a way to protect and make sure the film could be seen somewhat correctly in all theaters.

There has been a debate as to which should be the correct aspect ratio. 1:66 is the most common and is on the primary disc. The movie changes at 1:85, with some things being cropped. During the cab scene, the zoom is even more intense and sometimes the faces fall out of the frame during close-ups.

The Criterion disc has all aspect ratios available to watch. Needless to say I did not watch the movie three times for each ratio, but next time I may try a different one.

Even without watching the commentary, this disc has the most supplements that I’ve seen (yet) on a release. It is a worthwhile package that does justice to an historical film.

Criterion Rating: 10/10

Odd Man Out, 1947, Carol Reed

Odd Man Out was the first of a series of three films that essentially put Carol Reed into the conversation as a major auteur of the post-war period. The other two are The Fallen Idol and The Third Man, the latter of which is considered his masterpiece. It currently is #73 on BFI’s Sight and Sound poll and is consider the #1 British film of all time. Reed’s later work had some success, even if not quite as celebrated on a historical scale. He is appropriately remembered for these three, all of which have some similarities in style, yet are thematically different.

Odd Man Out is also remembered as one of the few films to feature Northern Ireland politics as a major setting. Another is John Ford’s The Informer, which would be a major influence on the Reed film. The politics of the IRA at the time were complicated, as they were in subsequent decades, and I don’t believe that Reed was trying to make a political statement of any sort. He simply adapted a novel with an Irish setting and used the political landscape as the backdrop to explore some major themes about humanity.

This was also James Mason’s breakthrough role, and I consider it to be one of the best performances of his career. His character Johnny is the leader of the local IRA group, and they rob a mill in order to acquire funds. Things go wrong when a renegade employee pursues the group with a gun. After a struggle, he shoots Johnny, who returns fire and kills the man. Johnny is wounded and tries to escape with his gang, but falls from the getaway car into no man’s land. From here, he is the title character as he literally is the odd man out of the group, although not by design.

Johnny is gravely wounded, yet because of the crime and fatality, the police are after the local rebel. The relations between the armed police and the citizens are the scenes where the political situation is addressed. Many of the locals seem to be on Johnny’s side whereas the police desperately want him captured and order restored. People assist Johnny in eluding his captors, sometimes by accident, but they do not immediately report his location. A household takes him in at one point, not realizing who he is, and they try to help with his injuries. Once they realize who he is, they let him go to wander the streets, but they do not turn him in. They simply want no part of the situation, probably because even though they support Johnny and his people, they do not want trouble from the authorities. Others assist him as well, and later when someone attempts to turn him in, it is to a local priest and only for some sort of reward.

As Johnny’s physical state deteriorates, his mental state follows. He fades in and out of consciousness, at times reaching a delusional state where he sees hallucinations. This is where Mason’s performance stands out. He often has very little dialog to say, and instead spends a lot of his screen time looking weathered and emaciated. When he does speak, it is often murmuring and sometimes rambling. Often his performance is merely physical, and he does as much with his movements, mannerisms and expressions as he does with words.

Even though Johnny is technically a rebel, murderer and criminal, he is portrayed as a benevolent person. When he is lucid, he wonders whether he accidentally killed the man at the mill. It pains him when he learns that the man is dead, not just for his own fate as a criminal, but because of his guilty conscience. He is expressly non-violent. At one point he hallucinates a policeman who he treats of as a confessionary, a plot point that will come back into play later.

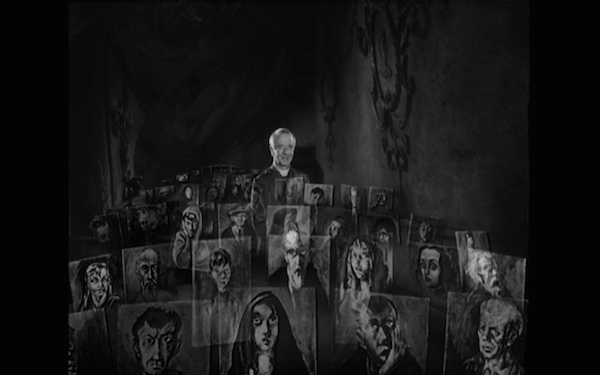

The church is continually involved in the film, both from a thematic sense and directly within the plot. Religion is at the forefront of the film, and becomes expressed through the character. When “Shell” gets wind of Johnny’s location, he uses an analogy of Johnny being one of his birds, and essentially tries to get a reward for this message from the church. Rather than giving any monetary reward, which they could not offer anyway, they instead give him the promise of spiritual rewards. By delivering Johnny to the church (and by extension, to God) “Shell” is one step closer to salvation.

As a product of the thick religious theme, Johnny becomes a messianic character. As he is being bandaged up by a local group, his physical health deteriorating and visions increasing, he quotes the bible. He says ““I remember when I was a child, I spoke as a child; I thought as a child; I understood as a child. But when I became a man, I put away childish things.” This bit of scripture is from Corinthians chapter 13, which is coincidentally enough, the chapter on “Love,” and is often quoted in positive and selfless context. Is Johnny becoming an instrument of God? Through his delusion, is he preaching for people to become more passive, loving, and accepting of God so that they will reach salvation? Is Johnny merely trying to achieve his own salvation out of guilt for his actions and the potential sacrifice to come? The film does not answer any of these questions definitively and it shouldn’t. That is one of its strengths, as it cannot give the answers, but it promotes spiritual and ethical exploration.

One of the constant motifs is about death. Tying into the religious theme, at one point the priest says, “This life is nothing but a trial for the life to come.” It is perhaps Johnny’s trial. In another scene, a character is asked what faith means. “Only one man had it,” he responds, probably referring to Jesus, although possibly in the context of the film, to Johnny. He continues by saying that “It is life.” Much of the film is concerned with whether Johnny will live or die, and it is through his love, Kathleen, that this answer is revealed at the end of the film. I will not give that answer here and spoil the film, but I will say that the ending punctuates much of what I have discussed here. It creates more questions than it answers, and that sort of ambiguity (along with a number of filmic strengths that I have not discussed) is what makes this a classic.

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements

Template for the Troubles: John Hill on Odd Man Out: 2014 interview with a scholar on Northern Ireland.

He calls this the first film to portray the urban Northern Island situation since the partition in 1921. IRA activity had not been significant before the film. During WW2, the members were interned. The film is sympathetic to the organization and Johnny.

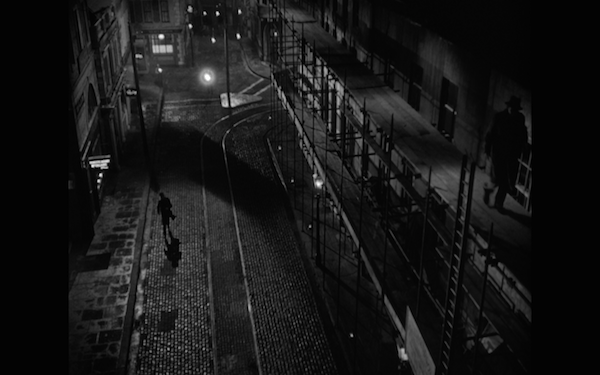

The city in Odd Man Out is not named, but is implied to be Belfast. There are some overhead establishing shots of Belfast, but most of the film was shot around Shoreditch, London or in Denham Studio in London. They created a model of the large clock, which would play a major part in the visuals, and they recreated the Crown Bar from Belfast in Denham studio.

Postwar Poetry: Carol Reed and Odd Man Out: This is a short documentary made for Criterion Collection in 2014.

They discuss the film in detail, from its origins when Reed read the book in 1945 and began shooting in 1946, to its legacy. One contributor calls it the British High Noon because you are so aware of the time throughout the film.

They speak about this film in the context of the other Reed films, including his prior and later films. One element that sets apart the three films is that they are shot at night and they exhibit an excellent use of darkness. Previously filming at night was not an option for Reed because he did not have the budget. There were other characteristics of a Reed film, such as that it had a cluttered frame and was shot documentary style.

Home, James: This 1972 documentary is a personal look through Mason’s eyes at his hometown of Huddersfield.

Mason narrates and they show scenes of people living, working, walking and going about his town. Much of the movie is about the economy, population, and industry. He spends a lot of time looking at the various local companies that operate in Huddersfield, and he speaks gushingly of the respectable type of person that lives in the town, whether they are a lower class worker or an upper class business owner. You could call it a fluff piece, as a critical words is hardly uttered.

Mason has a familiar slow and relaxed manner of speaking, which works well in film and his dialog benefits from this manner of speaking. I once joked that Mason’s voice would be enjoyable reading a phone book. After seeing this documentary, my opinion has changed. This film appears to have been created for local educational TV as a way of glorifying the city. Mason indubitably had plenty of hometown pride, but from an outsider, this is not exactly gripping subject material. It actually took me away from the film. A supplement about Mason would have been terrific, but this seemed like it did not belong. Film Rating: 3/10

Collaborative Composition: Scoring Odd Man Out: This is a piece about William Alwyn’s score with Jeff Smith.

I did not discuss many of the exemplary technical elements in my review, but the score is absolutely brilliant. Johnny’s theme is especially memorable and really fits well with his plight. As a result, this was my favorite supplement on the disc and it brought me back after seeing the dull documentary.

In a way, the score was experimental. Alwyn did not believe in “wall-to-wall” score with endless silence. He believed that there should be musical silence in plaes. He worked with sound editor to determine when to use score and when to use sound effects.

Smith plays all of the themes on the piano, which are for the characters of Johnny, Kathleen, Shell. Alwyn only deviated slightly from these themes. For instance he would play a delirium sound when Johnny hallucinates or loses his mind.

Alwyn was a major influence on the merits of pre-scoring a film and working with a collaborative team. Many famous conductors would write the score after the first rough cut of the film was completed. Alwyn pre-scored Odd Man Out based on the script. Others have followed, with the most notable example being Ennio Morricone with Once Upon a Time in the West where he played the theme for the actors.

Even though he had a highly successful career, Alwyn considered Odd Man Out his crowning achievement.

Suspense, Episode 460: February 1952 broadcast with primary cast.

This was another radio broadcast with cast members from the film. Since it is relatively short, it is an easy listen, even if the film language does not translate well to radio. Mason’s voice work is key in this version, beginning with him using his character to establish the heist debacle. “I’m hurt!!!” he yells loudly.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

An Autumn Afternoon, 1962, Yasujiro Ozu

An Autumn Afternoon ended up being Ozu’s last film. While it is a shame we don’t have a few more Ozu films in color, this was a solid ending to a legendary and masterful career.

For those who have seen Ozu films, the style is completely familiar. It focuses on domestic issues, is shot from a low angle with a camera that never moves, has a somewhat slower pace, and speaks solemnly on the intricacies of life and relationships.

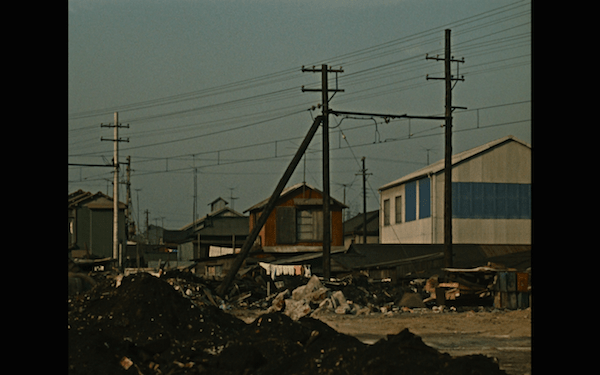

Ozu has plenty to say about the contrast between modernity, technology, commercialism, and a nostalgic fondness for the way things were. This is mostly established by his clever use of transition shots. The character scenes take place almost exclusively on interior sets. The transitions between these scenes show both a commercially vibrant Tokyo with elaborate signage, and also a worn down Tokyo by the seedier side of industry. These images are juxtaposed by characters that are concerned with baseball, refrigerators and golf clubs. Materialism is a vital part of their life, but is not portrayed as an entirely positive thing.

Ozu portrays men drinking together as pleasant experiences. This is where the men relax and enjoy each other’s company. Whether this happens as a large class reunion, or just two fellow Navy officers flippantly discussing the ramifications of the war, the mood is positive. This is punctuated by the score, which like most Ozu films, is always effective at setting a mood. Most trivialities are forgotten as men drink sake in the bar, reliving and enjoying the younger days while playfully tweaking each other. Age and virility are constant topics in these exchanges, and they talk often of marriage. Over time, these exchanges re-direct back to the family and the primary theme of the film. The tragic character of ‘The Gourd’ joins the classmates at their reunion and he is the picture of a fractured life, one that they do not want to repeat.

With Ozu there is always juxtaposition, and that is with family and married life. The family life is often portrayed as structured, formal and with a balance between commercial indulgences and domestic responsibilities. There is a subplot with Shuhei’s married son who wants an expensive set of golf clubs, which his wife stubbornly resists out of economic necessity. Even though marriage is discussed often in the film, this give-and-take exchange (which happens to be among my favorite sequences) shows a marriage in action. The golf clubs provide for a mild conflict between husband and wife, but also a way of expressing how aging men yearn for a leisurely outlet, which the wives must accommodate. This is juxtaposed with the Shuhei’s daughter taking care of her father, while being defiant when it comes to being the caretaker, knowing all along that her father and brother need a strong female in their lives.

Near the mid-point of the movie, after the marital dispute is resolved, the movie is basically rebooted. We see an image of a train, common in Ozu films, and then we see the same images and sets that began the film. We see the candy striped tanks of industry, followed by another exchange between Shuhei and his secretary. This is what started the film, and will propel it to the final act, which is that of Shuhei coming to terms with his aging and accepting the loneliness.

The ‘Gourd’ shows back up and is the catalyst for the remainder of the film. He is pitied, as he has degraded into a drunken restaurateur that caters to the lower classes. As he gets drunk, he laments on his life. “You gentlemen are so fortunate. I’m so lonely,” he says, and then later gives the fateful, tragic line of dialog that finally shakes up Shuhei: “In the end we spend our lives alone.” The former teacher has clung to his daughter, not letting her marry, yet he is still lonely. Shuhei has hitherto been in denial about his daughter’s readiness for marriage, which probably has to do with his reliance on her as a widower. He decides to let her go and let her marry.

The second half is heavier on plot, and as the pursuit of a suitable marriage candidate is explored, we lose sight of where Shuhei is headed. He is kind, thoughtful and considerate of his daughter, who we learn really does want to marry. She does not get her first choice, but she finds a satisfactory match. Her father just wants the her to be pleased with the best possible match.

Shuhei is left alone. After marrying off his daughter, he says: “Boy or girl, they all leave the aged behind.” His solace is working, drinking in bars and re-living the past with friends, whether they are his old classmates or war buddies. At the end he says that, “I’m all alone,” and subsequently sings the war song.

The ending is bittersweet. His family is happy and he is left forgotten. Even though he did the opposite of ‘The Gourd,’ both by finding a lucrative career and letting his daughter go, his fate is the same. Ultimately he has done the right thing, even if it leaves him with the inevitability of aging alone. At least he has solace in his war songs and the knowledge that, contrasted with ‘The Gourd,’ his family is his legacy and they have a bright future.

The same could be said for Ozu. He passed away the year after this was released, and western audiences did not discover him immediately, at least not like counterparts Kurosawa and Mizoguchi. He had a long and illustrious career, but one that was not compromised by intervention or commerciality. He did right by his films, and left a body of work that would stand the test of time.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements

Commentary: I was pleased to see David Bordwell. He is among the most reputable and admired film scholars out there. I have read him many times in film studies classes, and one class used his work as a textbook. Among his many books is Ozu and the Politics of Cinema, which is available as a downloadable PDF. He is one of the foremost Ozu and academic film scholars.

This is one of the better commentaries I’ve heard on a Criterion disc. Bordwell provides a wealth of information, not just on the background of Ozu and the film, but also about the shot selections, filming style, and how they were to used to convey Ozu’s thematic messages. One example is during the golf sequence with the brothers and sister-in-law, which Bordwell demonstrates with precision all the different cuts and camera changes, and how these interact with the relationships.

I’ll share a handful of factoids that I found interesting:

- Ozu establishes the premise early on during the office scene with his secretary. Women have two options in life. They can stay at home with their parents (father) or get married.

- In this era, working class men often had a rhythm of going to work, spending the evening out drinking, and return home drunk.

- It is a misnomer that American culture began penetrating Japan in the 50s. It actually started in the 20-30s. Ozu brought that into his earlier films. Kids in his 1930s films, for instance, want baseball gloves.

- The reunion of characters is also a reunion of actors. Many of those at the reunion were regular Shochiku players.

- Film was in decline during the final years of Ozu’s life. There had been a billion annual movie viewers in 1959, which declined to 500 million in 1963. That mirrored the decline of the prior decade in America. Part of the reason was TV, while foreign imports (especially American) also contributed to a decline in Japanese cinema.

- Sometimes Ozu mismatched the music. He would show a somber scene with cheerful music. Ozu was quoted as wanting “good weather music always.”

- Ozu filmed from a variety of different character ages, genders and perspectives. Most directors rely on autobiographical experience when portraying characters, but Ozu lived at home with his mother for most of his life, so it is impressive that he was able to relate to so many people different than himself.

- Ozu’s camera is almost always lower and rarely moves, but it is not on the floor. It is just lower than the characters in the frame, so the viewer is barely looking up.

- Ozu checked every shot through Viewfinder. Shohei Imamura was AD and got annoyed by him playing with continuity. Ozu uses it in this film with a soy sauce bottle, which Bordwell compares to a subtle Jacques Tati gag.

- Ozu’s mother died during production of film. Bordwell reads his diary entry where writes a poem beginning with: “Under the sky spring is blossoming ….” His grief materializes in the movie, with the film about a father also possibly being a film about a son.

Yasujiro Ozy and the Taste of Sake: 1978 excerpts of French TV show.

Ozu was “mysterious in his simplicity.” They talk about how he was a bachelor that lived with his mother for 60 years. He was usually later than his contemporaries when adopting technologies, including sound and color. He was unknown in the west until 15 years after his death.

A number of French critics discuss the filmmaker and his films. Georges Perec says Ozu searches for reality and does not find it. Instead he questions reality.

They show sequences of archery, Zen Buddhism, philosophy and even martial arts, which are prerequisites for Ozu’s work.

This release is an example that quantity does not always equate to quality. Usually a movie with a commentary and a single supplement would not be considered a major release, but the quality of the commentary and the gorgeous 4k restoration make this a must for any Ozu fan.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Beauty and the Beast, 1946, Jean Cocteau

When Beauty and the Beast was in production, the Second World War was in its final throes. The entire European landscape was ravaged and devastated by the war machine, and France had been under German occupation. Even though many filmmakers fled or were exiled, the industry continued in a limited capacity. To say that it had been a difficult time for the French would be a gross understatement. It had been horrific. When the film industry slowly began finding its legs, it would be expected that some escapism would be necessary. A bit of that can be found in Children of Paradise (my #1 of 1945). Few, however, would expect such a vast departure from reality as Beauty and the Beast.

Previous to 1946, Fairy Tales had primarily been almost exclusive to Disney animated films. In France, they were even less prominent, as many American films had not been shown during the war. Most people didn’t have a chance to see Pinnochio, Fantasia, Dumbo or Bambi until after the war. I’m a believer that time and context is a major consideration when evaluating film. This makes Cocteau’s project that much more special. For France, it was revolutionary filmmaking, unparalleled in time and space. One could argue that there never has been a live action film like it, and it has influenced many future films, such as the Disney remake and Demy’s Donkey Skin.

The story is familiar to probably every reader. Whether they have seen the Cocteau, they have undoubtedly seen the 1991 Disney version, which takes more from Cocteau than it does the original work from Beaumont. A princess ends up in an animated castle with a beastly creature. At first she loathes him, but grows to like and respect him, and eventually, well, you know the rest. This is a fairy tale after all.

What is also impressive is that Cocteau does not rely on state-of-the-art special effects to achieve is fantasy. He uses set design, musical score, costumes, make-up, cinematography, and mise-en-scene to create the fantasy. There are special effects, but they are only slightly more technical than the effects that Georges Méliès was creating during the early days of films. What’s more impressive is that we hardly notice that the effects are not technical spectacles. Everything else is so well done that it keeps us enthralled with what’s on screen. Cocteau uses artistry and not trickery to immerse us in this world.

I’ve already gushed plenty about this movie, but I have to gush just a little more. Jean Marais deserves credit for playing a number of parts in the film, but most importantly for his work as the Beast. One amazing aspect of the supplements was learning all that went into creating the character. Marais basically had to live in an uncomfortable layer of fur for hours, after spending up to five-hours being prepared in costume. Despite having no face to emote, he manages to perform enough with his eyes and his mannerisms that we understand the character’s feelings and motivations. On different occasions, we see the Beast as fierce, menacing, somber, mournful and jubilant.

Unlike a number of directors, past and present, Cocteau was a true artist. Rather than create a faithful adaptation, he made it his own by adding to the fantasy. The fantastical elements of the house are all Cocteau. He has human hands holding candles, pouring liquids, and human faces lining the walls, watching every move of the living. The fact that the house is alive adds to the mood and mystique. It is both unnerving and enticing to see a ashen face breathing smoke alongside the fireplace.

Beauty and the Beast was not without social commentary. The fact that the other living characters, especially Belle’s sisters, are untrustworthy, manipulative, and only looking out for their own gain speaks to the times. Belle utters a particularly scathing line of dialog that speaks more to modern society, specifically German occupiers and French collaborators: “There are men far more monstrous than you, but they conceal it well.” Cocteau is unequivocally comparing the monstrous nature of the peripheral characters with the real monsters who had governed France for the previous several years. Even if these monsters could sometimes be polite and smile, that does not change the fact that they are monsters. Beauty’s first paramour, Avenant, is very much like these two-faced fiends. He even has Belle fooled during the early portion of the film, but he is revealed to be just as cunning and dangerous as the outwardly evil characters. The Beast may not look like much and acts outside of social norms, but he is genuine. Belle knows what she will get with the Beast, and the more she gets to know him, the more she likes what he is.

I’m careful not to use the word “masterpiece” because it is a term that is too easily thrown about. I’ve used it on a few occasions, which is probably too often because it lessens the magnitude of the word. When I consider something is a masterpiece, I believe it is a truly original, creative and artistic piece of work that is unparalleled. Beauty and the Beast meets my definition, as I consider it the most important and the greatest live action fairy tale that has ever been made. It is the standard for which all tales should be measured, animated or otherwise.

Film Rating: 10/10

Supplements

Commentaries:

Arthur Knight – Film historian, recorded in 1991.

- Germans enjoyed the film. They took to the Aryan looks of the leads and ignored the subtext, although it was obvious in the minds of the French.

- Cocteau added a number of elements to the story. Avenant is an example of a character that was not in the original.

- It was a frustrating shoot because of continued problems. Airplanes would fly over the set, the weather was bad, and passing children would gawk at Marais in costume. There were many delays.

- Cocteau was critical of Alekant’s cinematography, especially the pacing of him setting up, thinking that imperfections would show in the final product. The opposite was true as the photography was celebrated.

- Knight speaks in detail about Cocteau’s homosexuality, contrasted with Noel Coward’s. He speaks about the relationship with Jean Marais, which lasted until 1947, where Cocteau met Edouard Dermit.

Sir Christopher Frayling – Writer and cultural historian, recorded in 2001.

- He gives more of a direct commentary to the scenes as they are shown whereas King provides more background details. Frayling mentions more instances where Cocteau takes poetic license or when the dialog is lifted from the book.

- Critics had attacked Cocteau for not being political. The prologue text is directed more toward them than the viewer.

- Cocteau had been poet, playwright, graphic artist, and a novelist. He was quite the artist, but hadn’t made a film since 1930 and this was his first mainstream film.

- Many of the castle props, including the living sculptures and supernatural elements were inventions of Cocteau. This is more surreal whereas the book was opulent. Disney used the Cocteau ideas for their version.

- Frayling contrasts between Beauty in this version and Disney. She is a post-feminist, intelligent woman in the Disney film, whereas Cocteau portrays her more as an object.

- In original story, Belle stays with Beast for three months while sisters get married to flawed individuals. Cocteau compresses the scenes.

- The fairy tale dates to 2nd century AD and wasn’t written until 1756. Passed down via word of mouth – “mother goose tale.”

- New Wave filmmakers loved Cocteau and Truffaut actually donated money for him to complete a film. He was not embraced in 1946-47.

Philip Glass’s Opera: 1994 opera created for the movie. It functions as another audio track that replaces the dialog. The Glass music is distinctive for those watching Errol Morris films (link to Thin Blue Line). It is a nice option for fans of opera and highlights some of the emotionality of the film. For many it may be the preferred score. It is extremely well put-together and inspired, but I prefer the original.

Screening at the Majestic: A short documentary about the filming with interviews.

During filming in 1946 in Rochecorbon, Tours, Cocteau watched the “rushes” in the Majestic Theater, which no longer exists. They found from the rushes that the film had a poetic and beautiful quality.

Jean Marais (Beast) and Mila Parély (Félicie) are interviewed. Marais respects Beaumont, the original author, but thinks that the magnificence of the film is due to Cocteau. I agree.

René Clément showed up and assisted, just after finishing Battle of the Rails, a prominent movie about the French Resistance. Clément was an AD, but was vitally important. They did not know then how talented he was.

Marais’ makeup took 5 hours to put on and was difficult to take on. The glue cut off his circulation.

Studied the art of Vermeer and others to get the lighting and set design. This is apparent in the scenes of Belle’s family’s house, as the interiors look very much like Vermeer paintings.

Interview with Henri Alekan: This 1995 TV interview with Director of Photography coincided with restoration.

It was a highlight of his life, in part because he was a beginner. It was difficult to make because the war was still going on.

Tricky to film in the dark, but he took on the challenge. Flemish painters like Vermeer, De Hooch, inspired him. Cocteau mentioned them repeatedly and encouraged him to go to museums to study the masters. This was just as important for his future as a cinematographer as making the film.

Secrets Professionnels: Tête à Tête: 1964 episode from French TV.

This short feature is about Hagop Arakelian, makeup artist. He worked for 33 years in the profession, learned from an actor in stage and silent movies in Russia and France.

As he has an actor in the make-up chair, he talks about his methods for applying makeup, how to make eyes look natural and other practices.

The list of directors he has worked with is staggering. They are basically the masters of French cinema. He demonstrates a number of different looks he can create, such as a black/white painted male face or a vagabond looking character with fake facial hair

This piece does not mention Beauty and the Beast, but he refers to it as his best work.

Film Restoration: The movie was not in jeopardy of being lost because all the negatives exist, but had degraded over the years. They replaced 150 frames with those before or after to fill in black frames, while computer procedures were used to correct sound.

Criterion Rating: 10/10

Jubal, 1956, Delmer Daves