Blog Archives

Black Narcissus, 1947, Powell & Pressburger

This post is part of the 1947 Blogathon hosted by Shadows & Satin and Speakeasy.

I was at dinner with friends a few months ago, one of whom happens to be a huge Powell & Pressburger fan. We were sharing thoughts on their 1940s output, pretty much raving about film after film. When we got to Black Narcissus, without thinking I said, “I just love the locations they used.” The thing is, they didn’t use locations, and I knew that. Everything was a set, but for a split second as I reached down into my memory bank about this film, my first image was the castle near a cliff at high Himalayan elevation. My thought was not of the matte paintings or miniatures, but the fantasy that they created.

The remainder of the film notwithstanding, the creation of this world is a marvel. Sure the matte paintings of the mountains in the opening sequence scream matte paintings. As they establish the “location” with a series of shots, it is easy to tell if you look carefully that they are using miniatures, especially viewing with modern eyes. As the film progresses, however, it begins to feel like real India. We get lost in that world, thanks to Michael Powell’s idea to shoot everything in the studio, and Jack Cardiff and Alfred Junge’s monumental work to make Pinewood Studios not only look like the Himalayas, but for it to look magnificent.

I could go on gushing about the sets, the use of color, but the pictures do most of the justice. Under this gorgeous backdrop is a story of isolation, perseverance, self-repression, and at the core, eroticism. Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) is charged with an expedition to open a convent in Mopu, to educate and assist the locals, in challenging, arduous terrain that slowly wears her and her fellow sisters down.

Deborah Kerr has proven repeatedly that she is a tremendous actress. One of her most impressive turns was the triple-role she played in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. In Black Narcissus, she has to play an entirely different type of character, but she pulls it off magnificently. As you see from the above tweet, she was poised and composed most of the time. Her performance shined in the nuances – the brief moments that she let her guard down. When a masculine figure like Mr. Dean makes a suggestive comment, we can see that it registers and she hesitates, but she is aware of her position of leadership and hiding her true feelings.

We see in flashbacks that Sister Clodagh was not always a chaste, innocent servant to religion. At one point, she had a love in her life and a carefree lifestyle doing something just for fun — fishing. During her moments of weakness in Mopu, she longs to return to those halcyon and unobtainable days in her life, lamenting the life of solitude that she has chosen for herself.

All of the Sisters face their own challenges, and one of the obstacles that Clodagh faces is dealing with attrition. However, her most notable adversary is Sister Ruth, played to perfection by Kathleen Byron. Ruth is stubborn at times, and highly sensitive at others. While Clodagh is quietly and stoically beginning to crack, Ruth is not just unraveling, but spiraling out of control. She falls the furthest from grace, and the rivalry between the two women makes the final act memorable, but this time I will not spoil the ending. Plus, I’m getting ahead of myself.

When one thinks of a nun movie, erotic is not a word that would come to mind, yet Black Narcissus is stacked with eroticism, which is the undercurrent for how the plot plays out. The world of Mopu is an erotic world. The nuns decide to take in one of the young local Generals (Sabu) for political reasons, and he dresses ornately and wears the titular cologne that he calls “Black Narcissus.” The naming of the scent speaks to the futility of the nun’s cause, and how the idea of civilizing the local “Black” population is a narcissistic exercise under the questionable philosophy of “White Man’s Burden.” Yet, the scent is intoxicating, and the Sisters find themselves attracted to the General’s charms.

The most sexualized character is a male, Mister Dean, who serves to mentor the women. He is their western conduit that informs them of the eastern ways, but he is also the most significant threat to their vows. He is a temptation for the women, and just like the constant wind, he slowly weathers down Sisters Clodagh, Ruth, and others. He is introduced wearing shorts and revealing clothing, and he is portrayed by David Farrar as a masculine outdoorsman. In one scene he arrives at their sanctuary not even wearing a shirt. What is the practical benefit of shedding clothing at elevation with the wind constantly blowing?

Ruth admires Dean from a distance, but he interacts with Sister Clodagh regularly. She manages to keep her true feelings close to the chest, but there are many suggestive lines of dialogue, quick glances, tiny fissures in her icy exterior that show she is aware of the temptation. In one early scene she notes that they are to talk business, and Dean responds that, “I don’t suppose you’d want to talk about anything else.” That other, unspeakable subject is of romance, or more specifically eroticism, voicing the prospective attraction they hold for each other. They play games, at times civil, at others hostile. In one scene, Dean sings Christmas Carols while drunk. Clodagh pushes him away, which is in part distancing herself from the threat by telling him “you’re objectionable when you’re sober and abominable when you’re drunk!”

The other sexualized character is Kanchi, played by a young Jean Simmons as her career was beginning. Kanchi is taken in by the convent as a pity project, but she is the antithesis of everything the Sisters represent. She is beautiful, wearing seductive jewelry and clothing, and even does a provocative dance. While the nuns have to keep their eyes aloof, Kanchi overtly presents herself as a sexual object. When the General reveals his cologne, the Sisters have no choice but to ignore the magnetism of the scent, but Kanchi holds nothing back. She savors in the charms of the General, and even though she is low by birth, she does everything in her power to win over the young, vulnerable man.

This sexual tension progresses throughout the first two acts, and it is the third act in which the Sisters, specifically Clodagh and Ruth, are faced with it directly. It is not a sword, gun or any other weapon of war that sets the film toward its thrilling conclusion, but a mere tube of lipstick.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements

Commentary 1988 with Michael Powell and Martin Scorsese.

This is a commentary I had already heard, so I did not re-listen/re-watch. I remember it being an excellent commentary, as was their commentary on The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Much of what they discuss is repetitive with the information found on the other features of this disc.

Bernard Tavernier: 2006 Introduction.

This was the first time they had adapted an existing work and not wrote their own screenplay. As Tavernier puts it, they adapted “between the lines” of Rumer Godden’s novel. We learned from The River that she was not satisfied with their adaptation and was careful to make sure Renoir would handle the material to her liking.

The Audacious Adventurer: 2006 Bertrand Tavernier interview.

Marie Maurice brought the book to Powell and Pressburger, and said they should adapt the film and she should play Sister Ruth. At first Powell did not pursue the film because he did not want to adapt other material. After the war, Powell had been tired of war films. Pressburger then remembered the book and talked him into the project, but Maurice did not get the part.

Casting was the next task. Kerr was the first to be suggested, but Powell discounted her because she was too young. Kerr heard this and when they had lunch, she convinced Powell that she was just right for the part. She said that age wouldn’t matter. Jean Simmons caused controversy because Olivier had contracted her to play Ophelia, and he took exception to her playing an erotic Indian. There was some friction between Olivier and Powell as they discussed/debated Simmons.

Jack Cardiff had not been a Director of Photography on a film, but had worked for Technicolor. Powell took a risk in hiring him for his first film, and the rest is history. He won the Oscar for Cinematography and would continue to collaborate with Powell, and had a highly successful career.

Powell decided on shooting everything at Pinewood because they would never be able to match the exteriors in India with shots inside a London studio. Cardiff and Junge had harsh reactions. They creatively looked for solutions, and decided to use miniatures and glass. Lucas and Spielberg have said that the special effects had never been matched.

Profile of Black Narcissus: 2000 making-of documentary.

They have interviews with Jack Cardiff, Kathleen Byron, and many others.

After a series of major successes and the previous year’s A Matter of Life and Death, Powell and Pressburger were at the top of their game. The question was what would they come up with next, which of course resulted in this ambitious project about ex-patriot nuns in the Himalayas.

The entire film had been shot in the British Isles. Not one frame was shot elsewhere. Pinewood became this exotic far away land. Cardiff said that after the film, they had letters saying that people had recognized places they had visited. This he felt reinforced that they had succeeded with the charade.

The tension between Sister Ruth and Mr. Dean was heightened by their off-set relationship. Byron says he had crushes on many women. As she puts it, “we were very close at one time, but it was not for very long.”

Painting with Light: 2000 documentary about Jack Cardiff’s work.

They have a number of interviews, including Martin Scorsese, Hugh Laurie, Cardiff and others.

Cardiff shows the mechanisms in the camera that shows how the color was captured. Scorsese says that films were continually being used for entertainment (as they still are) and Technicolor was used for popular genre films. It added about 25% to the budget

One thing Cardiff did was collected the best technicians around, and had a wonderful art director. It was a tough process and they needed Technicolor consultants on the set at all the time. They had to make sure the colors were right, and even had to dye the shirts to make sure the white did not contrast. The actual colors were bright “Technicolor colors.”

Vermeer was used as a model as to how to portray the light, but as Cardiff puts it, in the Vermeer paintings, the people did not move around. He used the Van Gogh pool hall painting as a model for another scene. Rembrandt was used to inspire other scenes.

Criterion Rating: 9.5/10

Summer With Monika, 1953, Ingmar Bergman

For this post I am mixing it up a little bit. Rather than do a formal review, I’m participating in MovieMovieBlogBlog’s Sex! Blogathon. Rather than do a formal review and/or analysis of this earlier Bergman film, I’m going to explore how sexuality was portrayed and how revolutionary it was in the world of cinema.

Monika and Harry are like many young, lusty couples. We see the courting process with them watching a romantic movie together. She is in tears while he yawns, which is typical, but through their brief time together they establish a deep, romantic connection. From there they escalate to a sexual relationship.

Even though Bergman had not launched on the internal stage just yet as a major auteur, by 1952-53, he had honed his filmmaking craft. The film language he used in films like Summer with Monika and previously in Summer Interlude would remain relatively constant throughout the rest of his career, but of course he improved and became more capable over time. He also showed early on a keen ability to demonstrate romanticism, sensuality and even sexuality. Because of the Hay’s code, American filmmakers had learned the power of suggestion through film language to hide the overt sexuality in film. Bergman borrowed some of these hints and developed a few methods of his own, but he also not afraid to dip his toes in the water and explore sexuality more directly.

We know that Monika and Harry begin an attempt at escalating the physical relationship because they are in the midst of some heavy petting when her father comes home. They quickly dress and act as if nothing was happening, which is a subterfuge that many (probably even Bergman) can identify with. They then meet on the boat and presumably have sex. They are in the same bed and there are vague suggestions at sexual activity. Harry loses his job and does not care. His new job is within the arms of Monika. As he ventures away from the city with her, we see the city from the boat’s point of view. The camera rocks back and forth, which we would expect from a floating boat, but in my opinion it is rocking because of the activities taking place within. Later in the film we learn that Monika has become pregnant. Conception most likely took place during these early scenes.

The sexuality transforms from suggestion to depiction as they reach the island. We first see Monika wearing a revealing bottom and a loose shirt, which she takes off. This is only the beginning of a series of scenes with a scantily clad Harriet Andersson. As they settle on the island, we see what is quite close to nudity. She faces Harry and removes her top, revealing her nude back. We then see her from Harry’s perspective, but his body blocks any nudity from showing on camera, yet his wandering hands clearly reach those same hidden areas. Monika gets up and runs to the beach and we see her naked behind, and then the film cuts to her in a natural pool. This scene is tame by today’s standards, but for 1953, it was quite scandalous.

The relationship and plot play out over the summer, and since this is not a traditional review, I’m going to skip these details. As they get settled back in the city, Monika becomes weary with her relationship and strays elsewhere. Bergman communicates this by simply having her look at the camera seductively when we know she is out of the house and away from Harry. This was also scandalous, because this was a sexually licentious woman. People in film were not often portrayed as straying from a committed relationship or marriage, even if it was only hinted at (although confirmed later) like in Bergman’s film.

In one of the final scenes, Bergman goes for the gusto. We see Harry raising his little girl, betrayed and rejected by Monika, but that summer still enraptures him. It isn’t clear whether the sexual escapades or the romantic moments are the most magical in his memories, but the version of Monika in the summer was a fairy tale. We see a flashback from his perspective of Monika in the same near-nude sequence as earlier, but this time the film does not cut as she runs to the beach with her rear exposed. She is fully nude, although this is a long shot so, again, not very explicit to modern eyes, but progressive for back then. Given that Harry remembers that one, erotic image, I think it was his personal sexual revolution that he longs for.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Ingmar Bergman Intro:

This is a brief introduction from 2003. Bergman felt affection for the film because of the way the screenplay came together, but also because of his introduction to Harriet Andersson. He had seen her in a stage play in fishnet stockings and lace, so he wanted her to be in the part. He did not go into the fact that they became lovers.

Harriet Andersson: 2012 Interview with Peter Cowie.

It had been 60 years and for her age, she looked remarkable. She speaks English well, with a strong accent. She talks about her origins in the industry, from being picked out to working with Bergman.

Bergman’s reputation in Sweden was very poor among actors at the time. He was reputed to yell and scream at them, and had his eye on young girls (which isn’t entirely inaccurate). She auditioned with an 8-minute shot where she was sketchy with her lines. She was surprised to get the part, which was a dream part.

She was not worried about the nudity. They were on an island so it felt natural, and the crew had seen it already. It felt liberating.

They talk about her looking at the camera, which was a scene that was appreciated by the French New Wave. She was shocked at the scene at first because this was something that wasn’t seen. People didn’t look at the camera. She thought it was strange, but went along with it.

Because of being lucky in getting this famous role, she was able to get roles with other directors and of course many future Bergman films. It was a break-out role for her.

Images from the Playground: .

This half-hour documentary is introduced by Martin Scorsese, who produced it through World Cinema Foundation. He was fortunate enough to live through Bergman’s career genesis from Summer with Monika up to Saraband. The documentary has behind the scenes footage from Bergman working on the film. It is from Bergman’s 9.5mm camera, and is almost like a home, silent video. It has narration from audio interviews of Bergman and his stable of actresses.

They talk about the production, such as Bergman discovering Harriet and talking about how gorgeous she was. It is interesting to see this commentary, but it is easier to just get caught up in the images and narrative. They take the documentary beyond just Summer with Monika. Bibi and Liv also participate. Bergman talks about the importance of all of these actresses and there are reflections on the fact that Ingmar was involved with them intimately at some stage.

This really is a magnificent little piece of film. It is the treasure of the disc.

Monika, Exploited!

Summer with Monika was a controversial picture in the states, and was hacked up and released as exploitation-fare with an English dub. This is an interview with Eric Schaefer who talks about how it became exploitation fodder.

During post-war period, distributors were importing films from overseas with adult content. These arthouse films were released in the exploitation circuit. Monika fit well with this market because of the brief nudity and sensuality.

Kroger Babb, an exploitation exhibitor, got the rights to Summers with Monika for $10,000. He then put in $50,000 into the film for cutting and dubbing. He got it through deceptive and suspect means, and Svensk took legal action because they soid the rights to Janus Films. They worked out a deal to release “Stories of a Bad Girl,” Babb’s version for five years, while Janus would release it for art audiences.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

The River, 1951, Jean Renoir

“The River had it’s own life, fishes and porpoise, turtles and birds, and people who were born and lived and died on it “ – Older Harriet

With The River, Jean Renoir is portraying two Indias. The native India is one of mystique and mystery to a westerner, but also one of serenity and a dedication to tradition. It is clear that he has fallen in love with that India (and he would later admit as much). The other India is the white upper class, post-colonial India, which Renoir may identify with as a westerner, but he seems to have mixed feelings about this India and portrays the characters as lost and confused.

Renoir uses documentary footage to show the real India and how the people live around the Ganges. In narration, we are told about “the animals and the people who lived and died near it.” We see people working on the boats; we see playing children descending stairs that reach into the river; we see people relaxing along the banks. The river is not only a place for sustenance, but it is also a place for escapism. The river is integral to the lives of the locals.

As for the English family that serves as the protagonists, they stay at arms length from the culture at which they are occupying, yet they are not disdainful. They respect and appreciate the traditions. The father prefers to walk through the bazaar on his way home and haggle over merchandise even though it is out of his way. The younger boy is fixated on snake charmers and wishes to learn their secrets. The English girls and Captain John are less attentive of their surroundings, and more concerned with their own distractions and affairs. They are “coming of age” in their own way while the river and the culture are relegated to the background.

The film has a great deal of voice-over narration, from Harriett, the English child protagonist, reflecting on her story of her first love presumably as an adult. It is her narration that we see both Indias, her insular version and the real one, yet she is educated and enamored by the true India and the magnetic lure of the river. This could mean that as part of her coming of age, she later came to an education and understanding of how special her surroundings really were, and how much the river influenced her life.

The primary white protagonists are Harriet, Valerie, and Captain John, and they form a sort of love triangle. Captain John has only one leg and is taking refuge in a foreign land as a way of escaping, a houseguest of their neighbor, Mr. John. He quickly befriends the family and the young girls. Harriet and Valerie both develop a crush on him, although they pursue it in different ways. Harriet is far too young for John, and hers is more of the fleeting girl crush. Valerie is older, who is not one of the family, but as an only child of a local businessman, she spends much of her days with Harriet’s family. She pursues John as a form of game, and she even toys with him and his affliction In one cruel scenario, she encourages John to play a game of catch and causes him to injure himself. Whether or not her heart is really into the affair is up in the air, but there is no doubt about Harriet. She is enamored by the visitor.

The white family has Indian connections. Dr. John has a mixed race daughter, Melanie, from a deceased Indian wife. Melanie serves as the mechanism for introducing Indian culture into the film, including a lovely fairy-tale diversion into the background of the God Krishna. Melanie also represents the contrast of both cultures. She has an English-centric upbringing, but as she gets older, she embraces her native culture. She even insists on wearing a Sari permanently. Bogey, Harriet’s younger brother, has a young Indian friend who encourages his foray into Indian culture and will be present for a later, game-changing scene.

These younger characters are all lost in a foreign land. In this way Renoir seems to be contrasting the privileged white class against the comfortable locals. Harriet is lost in love, which is a fruitless pursuit given the age difference. Valerie is lost in herself, and is more capricious as a teenage, only child, yet that does not seem to be an aspect of her person that she is proud of. Captain John is completely lost. He is coming to terms with his loss of a leg and being less of a man after the war, and has wandered from place to place, unsuccessfully trying to find somewhere he belongs. The least lost is Melanie, although based on her multi-cultural upbringing, she could have been portrayed as being the most confused. Even though in one sequence, she says to her father “someday I shall find out where I belong,” but she appears to have found it. She is resolute in embracing her native culture, while still embracing the love for her father and friendship with Captain John. Even though she is not squarely placed within the love triangle, it seems most appropriate that she end up with the visitor.

The heart of the movie is when the Indian traditions are shown. Here Renoir slows down the pacing and backs away from the narrative. It shows the real India, while also fragmenting the movie. The foolish meanderings of the young girls and their rivaling affections for Captain John seem to be insignificant compared to the beauty of the culture around them, which has been around for thousands of years compared to the teenage years of Harriet and Valerie. The previously mentioned Krishna story and the Hindu Festival with 100,000 lamps are when the film is the most pleasant, relaxing, and the most beautiful. Even though the coming of age stories are interesting, they pale compared to the story of the real India that Renoir puts so much care and love into showing us.

It is worth mentioning that Satyajit Ray and Subatra Mitra worked as Assistant Directors on the film. They were undoubtedly influenced by the work, and even though their later work would be unquestionably Indian, you can see some of the pacing and the mixture of documentary footage with narrative in their narrative films. I can see a lot of similarities between The River and The Apu Trilogy. The Renoir film is worth praise in its own right, but it also deserves credit for influencing the career of the man who would be called “The Father of Indian Cinema.”

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements

Jean Renoir Introduction:

The idea came to him when he was reading book reviews. He saw a glowing review of a book about India. He read the book and was convinced. All of the studios rejected him, thinking that a movie in India required tigers, Bengal lancers, or elephants. He then met an Indian florist that wanted to get into film. It was difficult at the time because Europeans and Americans did not understand Indian issues, so they had to film India through English eyes.

He heard about Rumer Godden, who was English but was born and lived in India. Renoir acquired the option before they met. They flew to India to make sure it was acceptable to shoot there, and Renoir was bowled over. He loved the country.

Martin Scorsese: 2004 Interview.

He went to movies with his father during his childhood and he describes this as one of “the most formative” experiences he had, and he compares it to The Red Shoes as the two best classic films in color. It was the first Renoir in color and the first Indian film in color.

India had a terrific canvas for color primarily because of the vegetation on the bank of the river. Many of the scenes he thought were reminiscent of a watercolor painting by Renoir’s father. Renoir apparently took a long time to arrange shots in a certain way, so possibly that was because of his father’s visual style.

Around the River: 2008 documentary about The River by Arnaud Mandagaran.

In a 1958 biography, Renoir called The River the favorite of his films. After Rules of the Game failed, he left France, made six films in the USA and then RKO dropped him after the failure of The Woman on the Beach. He left for India in 1949.

Kenneth McEldowney, producer, talks about his experience behind the film. He was first looking at one book, then that author recommended The River. He found that Renoir had the rights although he was not going to do anything with them. Renoir’s only condition was that he get a paid trip to India to make sure he wanted to shoot there, and he fell in love. Rumer Godden had also written Black Narcissus, and hated that it was shot entirely in a studio. She wanted Renoir to shoot in India.

Satyajit Ray worked up courage to ask for Renoir at hotel reception desk. He told the famous director that he was a great admirer of his, and Renoir was very nice. Ray “pestered him with questions, but he was very patient.” Asked him about French films, his father, and just about everything he could think of. Ray told him that he would like to make a film and described Pather Panchali.

Alain Renoir – His father had problems with the screenwriters. They would write something, and then he would film something completely different. Most became infuriated with him. Rumer Godden was the exception because she knew the country and the culture. This was one of the few occasions that Renoir and the writer collaborated well.

As for the Indian elements, they were unquestionably Renoir. He saw Rahda dance and wanted to meet her. The role of the mixed race Indian was not in the book, but was invented to bring more of India into the film and cast Rahda as Melanie. They found from the previews that Captain John was not sympathetic and the children acting was not as strong, so they over-emphasized the cultural moments and river sequences, which I think turned out to be a good move.

Jean Renoir: A Passage Through India: 2014 Criterion visual essay.

Water was a metaphor for life in Renoir’s work, and this was quite a good fit for him. He had been criticized for not returning to France after the war, but after The River, Renoir considered himself beyond nationalism.

The River was always his favorite because it finally made him an international director.

At one ceremony for Ray, it was said that Ray owed everything to Renoir. The elder director scoffed and said he owed nothing to him, and that he was the father of Indian cinema. Ray’s reaction was not recorded, but he later named Renoir as one of his major influences.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

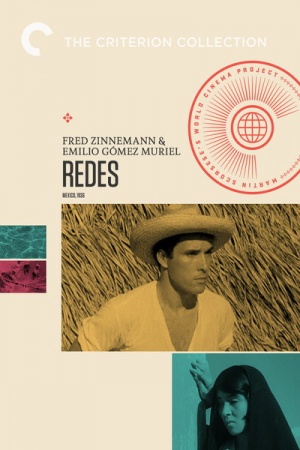

Redes, 1936, Emilio Gómez Muriel & Fred Zinnemann

Sergei Eisenstein famously visited Mexico in 1930 to attempt a film project, ¡Que viva México! which fell through for a number of reasons. Despite his failure, he left an indelible mark on the film industry. Initiated by a strong left wing state, the film Redes was produced in the vein of Eisenstein. While it is unquestionably a work of propaganda, it resembles the Soviet montage, highlighting the strength and solidarity of the workers while using editing techniques to portray the upper classes in a poor light.

The film is set in a small fishing village and begins with tragedy. Miro’s young boy passes away because there was not enough work for him to feed him the child. We see a number of sullen and somber expressions from Miro as he deals with this loss, while a boiling anger towards the system lies close to the surface.

The economic environment changes when the workers discover a bounty of fish, so many that there is enough work for everyone. The capitalist Don Anselmo makes sure to capitalize, and instructs his henchman to harvest as much as he can. “I just need people, boss,” he replies, establishing the reliance of labor in order for the prosperity to continue.

Miro works because he needs the money, but the memory of his child is not lost on him. He regrets that the work came too late. He along with others set forth into the water, and we see every stage of the process of fishing. Just like with Eisenstein, the film language celebrates the workers and shows their passion and ability. There are many shots that show the collaboration and cooperation it requires to mine these vast quantities of fish. The camera pauses on a muscular man pulling in the boats with the fish, highlighting the muscles that it requires. It is a well-done visual sequence that is shot documentary style and reminded me of Flaherty’s Man of Oran.

When the men are talking, one asks: “Who’s more stupid? Man or fish?” One response is a joke about women, but within the context of the movie, the question is valid. The men, at least the poor workers, are soon being exploited. When they return to the bosses with their massive fish haul, they are disappointed by the payment they are given. If this is the best they will get, then they will not be able to feed their families. They know the value of the fish, and some immediately figure out that they are being exploited to line the pockets of the rich.

One of the bosses reassures him that if they vote for him, he will clean everything up. Miro rejects him, knowing that he’ll say anything to get votes. “You know the big fish always win,” they say. From there, they decide to band together and unionize.

Even though the third act of the film is predictable, I’ll stop there. The last act is somewhat of a mixture between Salt of the Earth and an early Eisenstein movie. They use montage theory effectively. There is one scene where a significant incident takes place, which is followed by successive, quick cuts to stills of symbols, including currency, fish, and work, reinforcing the message that the workers needs to consolidate in order for their power to be felt.

The acting may not be spectacular, although the plot and message did not require them to emote. Just like, say, Alexander Nevsky, the ‘good guys’ acted and were portrayed as dignified, while the ‘bad guys’ were portrayed as greedy pigs.

Just like with the Russian and Flaherty films that I’ve already referenced, the strengths were in the visuals. Paul Strand, a noted photographer, did a fantastic job at getting the most of the location shots, where Muriel and Zinneman choreographed the action with precision. The film’s visuals and location shooting look ahead of its time, especially for an international film.

Film Rating: 7.5/10

Supplements

Martin Scorsese Introduction:

This was a short introduction for a film that Scorsese had never seen before the project began. It had three fantastic, and it was a state sponsored and a progressive, leftist film. Paul Strand was a visual artist; Fred Zimmerman had worked with Robert Flaherty (and I noticed some similiarities in shooting style), and Emilio Gomez was comfortable working in the Mexican system.

Visual Essay on Redes: Kent Jones, 2013.

Redes was conceived Mexican and shot at fishing village of Alvarado. It was financed by the Ministry of Education and Carlos Chavez. It was conceived as a rigorous Marxist analysis of modern living.

There were conflicts between Paul Strand and Fred Zinneman. Strand wanted still images and was reluctant to shoot anything moving, but of course Zinneman wanted there to be some action. The result is somewhere in between.

Reviews were favorable, but the movie was not widely seen. The negative was subsequently lost. Zinneman said that the Nazi’s burned it, but that has not been substantiated. The WCF took it over in 2008.

Top 20 of 1976

The 1970s were a great decade for German cinema. This list includes works from masters like Wenders, Fassbinder, and Schlöndorff. Another notable, Herzog, was omitted this year, but pretty much all four of these have been and will be regular fixtures on these lists.

My number one might surprise many because it’s nearly impossible to see. Here’s hoping that Criterion has the rights and will give it the release it rightfully deserves, preferably bundled with the other two road movies. It is a fitting end to the Road Trilogy, and ranks right up there with the best of Wenders work.

There are two Italian films, including my second favorite, which is probably also under-seen. It is a magnificent piece of character exploration, procedural, and political statement, with a whopper of an ending. It is the second time Francesco Rosi has appeared on one of my lists, which is fitting because we just lost him recently.

Technically this is after the American New Wave, which most people consider ended around the release of Jaws. There are still no shortage of tremendous American releases. Many people would list Taxi Driver as one of the best films of the decade. Network is still relevant in its skewering of the media. The rest are adventurous action movies, thrillers, and of course, Rocky, which has been unfairly vilified as a Best Oscar Winner.

1. Kings of the Road

2. Illustrious Corpses

3. Network

4. Harlan County USA

5. Cria Cuervos

6. Taxi Driver

7. All the President’s Men

8. The Tenant

9. Monsieur Klein

10. Marathon Man

11. 1900

12. The Outlaw Josey Wales

13. The Front

14. The Omen

15. Assault on Precinct 13

16. Chinese Roulette

17. Rocky

18. Coup de Grace

19. Carrie

20. In the Realm of the Senses