Category Archives: Essays

The Shining and the Family: Women at Work

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the topic of women’s liberation and the female role in the workplace was frequently and intensely debated. Like many political issues, the topic was divisive and controversial. The argument would manifest itself in pop culture and visual media. The Shining is an interesting piece of filmmaking because it constantly addresses social issues, and this is just one of them. It is most effective when negotiating the structure of the family and investigating the source of dysfunction. The movie comes out clearly against placing women in the workplace, claiming that in doing so, parents choose their own careers over responsibility for their children. Their absence from the child’s life, as is the case between Wendy and Danny, results in the child being exposed to dangerous influences that will disrupt their growth. The movie uses horror cinematic elements in order to make its case.

Many scenes in the film can be used to demonstrate this argument, but one that is particularly revelatory is when Danny Torrance interacts with the supernatural and enters the forbidden room number 237. The scene results in Danny being accosted by supernatural forces, injuring his neck. It comes at a significant point in the movie, taking place just after an uncomfortably awkward scene where Jack Torrance promises his son that he loves him and would never harm him. In the scene afterward, Wendy accuses Jack of violence towards their son. This sets in motion the course of events that will result in Jack attempting to murder his family.

The sequence takes place on a Wednesday, as shown by the title card, however we are not certain which Wednesday. It could have been a week or a month from the previous scene. All we know is that a period of time has elapsed, and judging from the intrusive editing and how the title card appears to be thrust onto the screen, the upcoming events are not going to be pleasant. This particular day of the week is significant in terms of the working mother argument because it is takes place in the middle of the business week, where the traditional father is away at work and the child is cared for by the mother. We will see shortly that things are different at the Overlook hotel.

Following the title card is an establishing shot that gives us an exterior view of the hotel. The camera is looking up from the bottom of a snow-covered hill, with trees bordering each end of the frame. The middle of the hotel is framed by two lone trees, a little ways apart from each other. To the left of this framing, we see a set of lights on. The light to the far left illuminates two windows. This is Jack’s work area where he is currently having a nightmare. Also on the left of the frame is another light, which is where Wendy is busy checking the boilers and making sure that everything in the hotel is functioning. She has taken on Jack’s role of caretaker, ignoring her child in the process. The only other light is on the other side of the hotel. This is where Danny is playing, hundreds of feet away, out of sight and earshot from his parents. The two trees in the middle of the frame are used here as a measuring device. They give us a visual representation of the physical distance between parents and child, and in a glimpse, how they are not able to prevent a horrific event from occurring.

We then cut to Danny playing with miniature cars and trucks on the hotel floor. The toy vehicles are colored either pink or blue. These colors represent gender roles, which in this case are his absent parents. There are five pink colored cars compared to three blue cars. The color of the cars here indicates the gender struggle in raising Danny, but by having pink being the dominant color, the movie is giving a visual cue that the female should be caring for the child. From out of nowhere comes a pink tennis ball. It interacts with Danny as he is playing with a toy car in each hand, one blue and one pink, hitched together. The tennis ball interacts with his play by slowly rolling into the center of the two cars, essentially dividing them.

The pink tennis ball is implying a gender interaction. It is breaking up the male-female balance with another feminine element, the origin of which is unknown at this point. It could be his mother or perhaps one of the specter twins that he has seen around. The music is frightening. Several instruments play a single, sustained note together, somewhat out of tune, which follows with silence and then repeats the same note again. We, the viewer are meant to expect that something sinister is happening. We would think that Danny, with his psychic abilities that have already warned him of evil forces throughout the hotel, would also suspect something dangerous lurking. At first, when he looks for whoever rolled the ball, he does appear to be a little frightened. The look on his face is inquisitive, showing that he detects something is amiss, and he takes a few labored, deep breaths.

When Danny is taking his deep breaths, his body language shows aggression. He is poised with his arms by his sides. His posture looks imposing, as a martial artist or street fighter might look before engaging in a battle stance. We can also read ignorance from his demeanor. Again, the audience suspects that the tennis ball rolling could be a threatening gesture. Two ghost children have already asked him to play with them forever and ever, implying that he die and haunt the hotel with them. Therefore we associate this attempt of innocent play as something to be frightened of, but his actions are not falling in line. Had Danny’s mother been around, she undoubtedly would have led him away from the potential horror. The film is claiming that her irresponsibility is what put Danny here in the first place.

There are several reminders of how alone Danny is on this hotel room floor. In between close ups of Danny’s reaction, we see long shots of the hallway from in front and behind Danny. Behind Danny are just one or two rooms. In front of him are four rooms, but the way the hallway is photographed make these four rooms seem a mile away. Danny is out in the middle of nowhere, completely vulnerable – a little kid on the moon.

Danny’s fear lasts for only a moment before a destructive curiosity takes over. Who rolled this tennis ball? Danny indicates that he thinks it is his mother. He calls out for her as he stands there, still in his aggressive stance. Of course there is no answer. He slowly moves forward and calls again for his mother. His fright has left him. His breathing appears normal. He is now curious as he moves forward. His mother, if given a voice, would stop his advance right there and send him in a different direction. We get a visual reminder of his other options, as there are labeled exits just to the side and behind him, but Danny presses forward.

The camera changes to Danny’s point of view as he walks, moving from side to side and bobbing up and down. We see the open room door, the dangling room key and we head straight for it. The eerie music continues, constantly warning us that we are heading for something unpleasant. Danny continues until the room key becomes visible. This is the ill-fated room 237, the same room that Dick Hollorann warned him not to go near. The doorknob with the blood-red key ring is at eye level with Danny and the camera, still in first-person view. Danny stops for a moment in front of the room key and calls again for his mother, this time asking if she is in the room. By addressing her again, he reminds us that her absence is irresponsible.

Once Danny and the viewer get a glimpse of the inside of room 237, the scene dissolves to Wendy going about her work, checking the boilers and other machinery. The choice to dissolve here is interesting. This was not used for any of the other cuts. Kubrick is saying something here. The room has been developed to be an evil, ominous place. Once we get a look at it, we are placed back into Wendy’s workplace. On top of that, Danny is calling for her, expecting her to be inside the room. By using these techniques, we are being given the horror of room 237 and the idea of a woman working and neglecting her child on the same level. Adding this up, we understand that it is the fact that the mother works that is evil.

In case the audience is not sure of what is being said, it is immediately clear as Wendy’s scene unravels. As she is going about her work, she hears a scream. Having been with Danny for the past minute-and-a-half, we expect it to be his scream. We find out that it is Jack’s. Wendy runs for him and discovers that he has had a horrific dream, one in which he kills Wendy and Danny and chops them into pieces. Wendy takes on a motherly role with Jack, but not her son, who we know has undergone his own horror. His is real, whereas Jack’s is imaginary. We meet up with Danny shortly and find that he is injured. Since the mother was not there, she does not know how or why this occurred. She places blame on Jack, which completes his transformation that brings events to a climax.

With this short scene, Kubrick is making a statement about the role of parents in a child’s life. He feels that the mother should be the caretaker for her child, and she is solely responsible if anything goes wrong. He uses several cinematic elements and horror film conventions to drive his point home, including clever editing, scary music, symbolism within the mise-en-scène, and the cinematography. This same idea is corroborated by the plot and dialog of the movie, and is resolved scene after scene. In essence, the movie is about the dysfunctional Torrance family and who is to blame for their unraveling. Kubrick is arguing that if Wendy and Danny stuck together, they would have avoided, or at least minimized, the abuses inflicted by an unstable father.

The Merchant of Four Seasons, 1971, Rainer Werner Fassbinder

If you can say one thing about Fassbinder’s films, you can say that he was adept at portraying and processing human feelings. These were usually negative human feelings. For example in The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant, he explored vanity and loneliness, whereas in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, he explored isolation and rejection. There are many other examples, such as Fear of Fear, which is a lesser-known Fassbinder that captures anxiety better than any film I’ve ever seen. With The Merchant of Four Seasons, the emotion that he captures is depression.

I’ll be honest that depression is something I don’t understand. Sure, I’ve had bad days and been down in the dumps. Who hasn’t? I’ve known people that have been depressed, and I’ve had a tough time connecting with them. One friend sent me this cartoon link from Hyperbole and a Half, which helped me understand depression to a certain extent. I can never understand it as well as people like this friend or (likely) Fassbinder experienced it, but a film like The Merchant of Four Seasons gets me closer.

As fair warning, this is a film that requires spoilers to discuss properly. If you haven’t seen the film or are spoiler sensitive, then I would not read this entire post.

The character of Hans is a disappointment to most in his life. When he returns from the military, after finding out that someone else did not make it home, his own mother says, “the best are left behind while people like you come home.” We learn later that his military career ends with a sexual transgression. He then becomes a cart merchant, peddling fruits for a small profit in order to support his wife and daughter. When he isn’t working, he drinks with his friends and does not want to be disturbed. In one pivotal scene, when his wife Irmgard (Irm Hermann) demands that he come home, he throws a chair at her. Later, when questioned, he beats her.

His family scorns him and thinks of him as a disappointment. They shun him after the case of abuse, siding with his wife while he beckons her to come back. The only person in his corner is his sister Anna (Hanna Schygulla), yet she has a minor role and is mostly ignored. When we see the family on screen, they serve the purpose of reminding us how worthless Hans is in their eyes. It’s no wonder that he feels such helpless despair.

Hans suddenly has a heart attack, and is forced to stop drinking and is not allowed any heavy activity. Given his prior anguish, one would think that this would push him further into depression, but the opposite happens. He takes on the role of proprietor, hires a productive employee, and enjoys profits. In a later scene, his family is surprisingly pleased with him. In their eyes and his, he has succeeded as a cart merchant.

Things come tumbling down due to another theme among the primary characters – weakness, especially in terms of their sexual proclivities. Han’s weakness with an admirer is what ruins his military career. In an early scene, he delivers fruit to an woman and is chastised by his jealous wife for spending seven minutes with the woman. We learn later that there is a hint of an affair happening at some point, which possibly happened off-screen during these early scenes. While in the hospital, Irmgard has an affair of her own with a taller, more masculine man. That man coincidentally ends up becoming Hans’ successful salesman. In my opinion, this was too coincidental, but it was a necessary plot development to take Hans further down in his slide.

Irmgard is a confounding character. She rekindles her relationship with Hans, even when he is employing her former, temporary lover. It is in this period that his depression begins to take shape again. Even before he discovers the truth, which comes up after he catches him skimming money from his sales, a strategy in which Irmgard suggested. She is the mystery. Fassbinder usually portrays women as strong and sympathetic characters, but Irmgard makes some baffling decisions. At times she seems to want to undermine Hans, while at others, like in the image above, she is saddened by his downfall.

Hans’ depression reaches such a low that he decides he wants to die. We learn through flashback that this is not the first time he’s reached this low of a feeling. When being whipped by an enemy soldier, he faces certain death, only to be rescued at the last minute by fellow soldiers. Rather than thank them, he asks them, “why didn’t you let me die?”

The final drinking scene is the culmination of the burdensome weight of all those who he has disappointed, including himself. Because of his health condition, he holds the gun that will decide his fate. He commits his suicide with bitterness and no regret. He even dedicates each shot to a certain someone who has wronged him. This is his way of getting back at the world.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements

Commentary – Wim Wenders, 2012.

Wenders talks about how it is unusual to comment on a film from a friend and colleague that died 20 years ago. He gives a commentary you would expect from Wenders. He speaks slowly and relaxed. He is not the type to comment or analyze every little scene. Even though I like analytical commentaries, I also like this type because it is more like you are watching the film from a friend.

- Fassbinder did everything himself, including writing, directing, sometimes acting, editing, sometimes producing. Working on so many projects as Fassbinder did required him to be working on the next one while he was finishing the last one. Wenders says that the speed in which he worked would eventually kill Werner.

- Wenders loves film, and he especially loved Hans Hirschmüller so much that he cast him in Alice in the Cities.

- He had such a strong ensemble that he would often cast his major actors in small roles. Hanna Schygulla and Kurt Raab are examples here. Of course Schygulla, in Wenders words, would “become one of the major stars of German cinema.”

- Back then, selling fruit off a cart was a real Bavarian profession. He points out the fact that the people speak with a distinct Bavarian accent, but that does not come across with subtitles.

- Prior to the German New Wave, the most successful German films were either Westerns or softcore porn. This direction into character-based melodramas was a major shift. They learned their craft from American films.

- He talks about the New German Cinema experience. They were not in each other’s way, had nothing in common, different perspectives, different missions. They helped each other, had no envy, shared cast and crew. Fassbinder was way ahead of them. By this time, Wenders had only made two short films. They were not bound by a cultural aesthetic, and never discussed content, style, but more about distribution, projects, etc.

Irm Hermann: 2015 interview.

She had no formal training, but got lucky when she met Fassbinder and he pulled her off of an office desk and put her in front of a camera for The City Tramp. He quit her job for her. Fassbinder was charismatic and started in the theater. She had no training save for how Fassbinder trained her. She didn’t want to do the sex scene, but Fassbinder was discrete and sent everyone out of the room. She is grateful for the film because of the Douglas Sirk-like close-ups. Her and Hirschmüller won German Awards, as did the film. and that was a major deal.

Hans Hirschmüller: 2015 interview.

The role of Hans was written with him in mind. Fassbinder wanted someone down to earth and simple, which was really what he was at the time. He knew the types of merchants that he would play. Fassbinder didn’t tell him anything about the role. He just made him read the script, and asked if he approved.

They did not often do multiple takes. Usually one or two, sometimes three, but very rarely four. Rehearsal is when they would improvise, never during the scene.

It was a tough role for him because he had to face death like he never had in his personal life. He had trouble getting to the position of being helpless. The scenes where he was depressed were the toughest for him.

Eric Rentschler: Interview with film historian and professor at Harvard.

This was the film that put Fassbinder on the map. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive. Some said it was the best film to come out of Germany in years. Fassbinder had been working productively prior to this, but his rise out of Merchant was meteoric. Early films were bleak and resembled neo-noir. You could tell that Fassbinder was a student and fan of film.

Fassbinder is good at showing what character’s are capable of, both good and bead. Irm Hermann is an example of this because she has adultery and is planning on leaving her husband on one occasion, yet adores him in other occasions.

The film was based on his uncle, who had fallen from a high position and ended up as a fruit salesman.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

The End of the Studio System, Part 3

THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL

This is the third post of three that is part of the Classic History Project Blogathon hosted by Movies Silently, Silver Screenings, and Once Upon a Screen, and sponsored by Flicker Alley.

Part 1: The Foundation Slips

Part 2: The Beginning of the End

During the 1950s, the film industry crashed precipitously. By 1953, only half as many people were seeing movies in theaters as they were the decade before. By 1957, only 15% of the population went to the movies at least once per week. Meanwhile, the US was in the midst of a post-war economic boom. People had money to go to the theaters. Why didn’t they?

It is too easy and convenient to pinpoint the Paramount Decision of 1948 as the reason for the downfall of the studios. It surely was a catalyst, but there is no single answer. Divorcement was one of many reasons for the downfall of the studio. A lot of people blame television, which is also fair, but again, just one of many reasons for the decline. It was a perfect storm of legislative, technological, and socio-economic changes that drastically reshaped American society, and subsequently, American media.

MIGRATION

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the armed forces returned home to economic prosperity. With improvements in automobiles and extra disposable income, people had the opportunity to move away from the big cities and into the suburbs. Levittown is a famous example of these communities, but there were many like it. The suburban sprawl began rapidly in the 1950s and continued gradually.

Another major driver of this migration was the Baby Boom. People were having kids and wanted to live in quieter, more relaxing places to raise them. This was the age of the nuclear family, and people wanted to spend their time raising children or participating in family and group activities.

It was not easy to bring movie theaters to the suburbs. The old movie palaces had been urban spectacles — vast buildings that were usually in the heart of downtown and could hold massive crowds. These theaters attracted people to the city and were the source of the studio profits. As people moved away, these large palaces eventually faltered. It was a challenge to bring movies out to the suburbs because the population was so scattered.

ECONOMIC BOOM

With this new period of prosperity, people wanted to spend their money on more substantive activities than going to the movies. As noted earlier, the movies were seen as low cost and short duration entertainment. People wanted to spend their money and time on memorable adventures rather than fleeting escapes from reality.

This was also the time period where the 5-day work week was becoming the standard. People had their weekends free and wished to spend them on activities such as homemaking, gardening, and sports. With transportation and money to burn, people wanted to see the world on vacations rather than see artifice in the movie theater. Prosperity actually hurt the studios.

TELEVISION

The role of television in the downfall of the cinema is hotly debated. Many consider it to be a direct cause for the studio’s demise, while others see it as more of a symptom of the economic transitions happening in society. Regardless of where experts stands on the topic, television was a factor. It quickly became a popular appliance and allowed people the convenience of consuming media at home rather than going to the theater.

The television boom began in the late 1940s and continued throughout the 1950s. The growth was rapid. By 1960, 87% of the population had a television. Unlike the movies, where people sit in dark rooms, television was a social activity. People would gather together and watch a program at somebody’s house.

The programming on television was passive and light, not as deep and profound as that seen on the silver screen. Much of the programming on television replaced the B films that the studios relied on for small profits. Television also took the pre-movie content away from theaters, such as cartoons, newsreels, and short films.

THEATERS IN THE 1950s

The large movie palaces gradually went away in the 1950s. They were replaced with arthouse cinemas, which would attract a higher brow, more intelligent and sophisticated moviegoer. The demographics for these films were older and more cosmopolitan. Many of these audiences watched films that are discussed here at this blog.

There was a foreign film boom in the late 1940s and 1950s, many of which took hold and became popular in the United States. Among these imports were the post-war Japanese (Kurosawa, Mizoguchi), Italian Neorealism (De Sica, Rossellini, Fellini), French noir (Melville, Clouzot), and later the French New Wave (Godard, Truffaut). Foreign films were not subject to the Hays code and often were provocative with sensual situations. Bitter Rice was a film that was noted for sexual suggestion. The Bergman films of the 1950s also titillated audiences, such as Summer with Monika as an exploitation film. Compared to the American films, the audiences were still small, but these foreign films pushed the boundaries and played a part in removing the Hays Code.

One creative way to get theaters to the suburbs was through drive-in movie theaters. They were relatively easy for exhibitors to open because there was plenty of land available in the suburbs. We think of the drive-in theaters differently than what they were in the 1950s. They were not just for watching movies, but were a hotbed center of activity. Of course there were the movies, but there was also food and other amenities. Some would even offer laundry services. The drive-ins were eventually seen as immoral and degenerate. Kids would use the drive-thrus as a place to discretely bring a date or get into trouble.

The next suburban theater was a bi-product of the advent of the shopping mall. Every mall would eventually have a multi-plex and most still remain today. The reasoning was that the mall would draw consumers, and movies were a way to take a break between shopping.

THE STUDIOS ADAPT: TEENPIC

This may seem incomprehensible, but the studios had not done any major market studies prior to the 1950s. However hubristic it may sound, they did not have to prior to the 1950s. So many people went to the movies that it was almost a waste to track where they came from. Prior to the 1950s, they ignored teenagers because they thought of films as family outings. As the war babies started to reach adolescence in the 1950s, they became a large market with free time and allowances to spend. During this time, Hollywood finally started using modern marketing techniques and determined that teenagers were regularly going to the movies. They subsequently targeted these teenagers with their content.

Even though it was a social picture, Blackboard Jungle was a surprise success. It was also notable for using a rock and roll song, Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock. In 1955, Sam Katzman ushered in teenage rock and roll movies starting with the film version of Rock Around the Clock. This trend continued, and soon Elvis Presley movies gained traction. His debut was in Love Me Tender, which was successful due to his popularity with teenagers. He starred in a total of 33 films, most of which range from bad to mediocre, but they attracted fans. There were plenty of other teen film franchises. Gidget was hugely popular and started a franchise of its own, plus it ushered in the Beach Party film. Teenagers came out in droves to watch these movies.

THE STUDIOS ADAPT: TELEVISION

As already discussed, television began by piggybacking on the radio concept of nationwide “live” content. That carried them for a short while, but soon a more diverse range of content would hit the screens. The studio system is responsible for much of this content.

The independent producer model took hold with television. Major Hollywood players began dipping their toes into television in order to make profits. David O. Selznick came out of retirement to do this very thing. He achieved success with a program called Light’s Diamond Jubilee, which was broadcast on all four networks and seen by 70 million viewers. This was a staggering number for the time period. Other similar jubilees preceded Selznick’s and would follow him. As he was before with film, he became obsessive with the project and this was the final Selznick TV production.

The most notable independent production company was Desilu, founded by Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, and popularized by their hit show I Love Lucy. That was not their only success. They would release The Untouchables, Star Trek and many others. Delis proved that independent producers could become television tycoons.

Eventually all of the major studios would transition to television. As already discussed, Disney was the first to find success with Disneyland and later Walt Disney Presents. After early failures, the studios gained a foothold in this new arena. They still had studio space that was not being used, so they started putting together television programming. Warner Brothers signed a deal with ABC and launched Warner Brothers Presents, which was their first foray into television. They continued their relationship with television, using the same production methods as their old B movies and found success in television. They became known for their westerns like Cheyenne, Maverick and Sugarfoot.

Universal/MCA became the unquestioned leader among studios in television production. Their continued production of B pictures after the Paramount decision helped for a smooth transition from the large to the small screen, and they transplanted many of their successful film franchises to television. They also launched popular shows of their own, such as Leave it to Beaver, Alfred Hitchcock Presents and several others. Today they are a multi-media conglomerate, NBC Universal, that own various entertainment properties.

THE FUTURE STUDIO SYSTEM

As the tumultuous 1950s ended and the 1960s began, the studios had reached a level of comfort and stability. They all continued working in television, using their facilities for new programming, and they continue to be major players in television today.

The independent producer model, as previously discussed with Selznick, became the norm. Professional producers such as Hal Wallis and Robert Evans worked closer alongside the studios and the talent. Evans had previously been head of Paramount until he obtained success with Chinatown in 1974. He then stepped down and worked as an independent producer, yet he continued to produce films for Paramount.

Steven Spielberg’s Jaws was the first blockbuster hit, and it revived the studio system to a certain degree. They were still divorced from vertical integration, but they began to focus on large blockbuster releases, a trend that continues today. One could argue that Jaws saved the studios, and ever since they have relied on blockbuster franchises for their core profits.

WHERE ARE WE GOING?

We are now in the digital age, which seems to be another period of transition. Box office revenues are still high, but more and more people are watching movies at home, either through streaming services like Netflix, Amazon, Hulu or Video on Demand. Premium content that used to be found only on the large screen as a film can now be found on cable as an expensive mini-series. Popular shows like Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead would not have a chance twenty years earlier.

Predicting the future is impossible, but sometimes the past informs the future. We could be heading into another transition into the digital change that will change how people consume entertainment in the future. Only time will tell what this will mean for cinema, television, and visual media in general.

SOURCES

- Anderson, Christopher. Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties.

- Maltby, Richard. Hollywood Cinema.

- Sarris, Andrew. The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968.

- Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era.

- Staiger, Janet. The Studio System.

- Staggs, Sam. Close-up on Sunset Blvd: Billy Wilder, Norma Desmond, and the Dark Hollywood Dream.

The End of the Studio System, Part 2

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

This is the second post of three parts that is part of the Classic History Project Blogathon hosted by Movies Silently, Silver Screenings, and Once Upon a Screen, and sponsored by Flicker Alley.

UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), the Hollywood Ten, and the subsequent blacklistings are large topics in their own right. They did not directly impact the downfall of the studios of the system, but they were yet another symptom that something was broken. The anti-communism movement and the fallout contributed to a great deal of pessimism within the industry, while also removing talented individuals that included actors, directors, writers, and even common crew.

The hearings and inquiries into Hollywood began in 1947 where they were trying to identify Hollywood filmmakers who had ties to the Communist Party, and were subsequently trying to influence Americans with a leftist agenda expressed through film. The Hollywood Ten refused to testify and were blacklisted. Many other notable individuals would later be blacklisted, including Charles Chaplin, Orson Welles, Martin Ritt, John Garfield, Judy Holliday, Dashiel Hammett, and countless more. Some cooperated and testified, naming names. This list included Elia Kazan and Sterling Hayden.

PARAMOUNT DECISION AND REPERCUSSIONS

The Paramount Decision of 1948 was the smoking gun that effectively ended the studio system’s dominance of the industry. All of the tricks like block booking and blind bidding were immediately abolished, once and for all. The entire decision can be read here. It was a detailed decision and a pointed one. The studios had to divest themselves of their theater holdings and operate as production companies only.

The decision was devastating and there were major repercussions. Overnight, the landscape had changed and the studios had to make drastic operational changes. The fallout would pave the way for television and a new era of Hollywood filmmaking.

Since the studios could no longer push their lower quality inventory on theaters, they had to scale back on B picture productions. Most of the studios focused solely on A pictures. This meant there were also fewer overall productions. This meant fewer jobs, at least in film.

Each studio transitioned differently. Universal was one of the outliers that remained in the lower grade feature or B picture business. They revived the Abbott & Costello franchise, and originated some other franchises that would eventually land on television.

The studios now had to make deals directly with the talent. In this new world, they resembled the independent systems like the Selznick system. Since they had lost leverage, the negotiations were not always in their favor. They made deals with filmmakers, such as Alfred Hitchcock as independent producers and directors. The talent that was in demand held substantially more leverage than they did under the old system.

The directors, actors, and all of the talent were essentially free agents. They made films for different studios. During what most consider to be Hitchcock’s best work in the 1950s, he worked primarily with Warners and Paramount, but he made North by Northwest with MGM. Directors like Hitchcock developed more into auteurs, whereas in the previous system, producers such as David Selznick and many others (Val Lewton for instance) had some sort of authorial control.

TRANSITIONS

Each studio handled the changes differently. With television coming into play, the industry was shaken up dramatically. At first the studios were reluctant to get into bed with television, which they saw as competing for the same viewers, although that changed once some social-economic realities set in.

Lew Wasserman formed MCA, basically a talent agency, and he became a power player in the scene. He functioned similarly as David Selznick did in the 1940s after getting out of feature production and farmed out talent to the various studios for a profit. MCA acquired talent such as Jimmy Stewart, and leveraged them against the studios to benefit their clients. One of Wasserman’s major deals involved Jimmy Stewart and Universal, where he negotiated a tax-friendly deal for Stewart to get a large percentage of the profits. This in a similar vein as the deals that Capra and others had made to get paid in capital gains, although far more generous. Stewart was able to obtain 50% of the profits of Anthony Mann’s Winchester ‘73. This was an unprecedented number, and Stewart was also more involved in other aspects of the production. This was new and shaky ground for the studios.

Here is an interesting and not very flattering piece on Wasserman from Slate.

Studio head Louis Mayer left MGM in 1951 after a power struggle with Dore Schary, the then head of production. This turned out to be a fortuitous move for MGM, as they were able to survive under Schary under the strength of the musicals. Musicals such as Singin’ in the Rain and An American in Paris were massive moneymakers for the studio, and there were plenty other successful musicals on a smaller scale. The studio continued churning them out and they outlasted all other studios at remaining profitable and prominent without making drastic changes. By 1955, most of the musical profits had run their course and MGM transitioned just like the rest of them.

THE STUDIOS AND TELEVISION

There was reluctance for the studios to transition to television. It was thought to be a lower quality product, and in the beginning, that was true. At first there were mediocre offerings with an emphasis on being “live,” which is something that separated TV from film. Over time, the TV content transitioned to resemble the B features that the studios had formerly cranked out. In many cases, the same studio lots that were used for B films were used for TV shows. As the film industry went through a downfall, they had no choice than to jump into the arena.

By 1955, most studios had made their attempts at launching television programs. Disney, MGM, Warner Brothers, and 20th Century Fox all made attempts, yet few of them were successful. Disney was the only significant success with their show Disneyland, which was partly because it was tied to their popular theme parks. Many studios noticed how well Disney was able to transitioned and tried variations with mixed results.

A watershed moment came when The Wizard of Oz was licensed to television and scored huge ratings. The studios again took note and unloaded their film inventory to television for large sums of money. Television became a second-run outlet for older film inventory. Back in those days, there was not much of a secondary market for film inventory, so this was a pivotal moment.

There will be more discussion of the studios and the transition to television in the next section.

Next: The Downward Spiral

The End of the Studio System, Part 1

THE FOUNDATION SLIPS

This is the first post of three parts that is part of the Classic History Project Blogathon hosted by Movies Silently, Silver Screenings, and Once Upon a Screen, and sponsored by Flicker Alley.

These essays are based on previous research that I have done and I will share my sources at the end.

POWER

On an early 1948 evening, the Wilders and Goldwyns dined together at a Romanoff’s in Beverly Hills. It was a popular restaurant for the industry, with many top-flight stars showing their faces regularly. The foursome’s dinner was interrupted by an elderly, disheveled man, looking gaunt and possibly drunk. He approached the table and gave Samuel Goldwyn a tongue lashing, criticizing the mogul for the unwarranted success he had achieved. He ranted that “here you are, and I ought to be making pictures, I’m the one.” Goldwyn was shaken, and after the man left the table, revealed him to be none other than D.W. Griffith, one of the most important and influential silent filmmakers that ever lived. The system had made him, and then chewed him up and spit him out. A couple of decades later, and it could have been the studio system saying the same thing to another dinner party.

The studio system was a behemoth. They consisted of the “Big Five,” which entailed Fox, MGM, Paramount, RKO and Warner Brothers, plus there were also Universal, United Artists, and Columbia, often referred to as “the other three” that had plenty of power. The studio controlled the movie process from production to distribution to exhibition. They wrote contracts with actors, writers, directors, producers, and virtually all involved with the industry. They released the “A” pictures (prestigious star vehicles) to the movie palaces, while the lower budget films, often genre or from recycled scripts, comprised the “B” pictures.

During the Great Depression, films were considered to be a populist, relatively inexpensive form of entertainment. Much of the content of the films of the 1930s pandered to the masses, and despite experiencing losses during a few bad years, the studios more or less continued to rake in the profits. During the Second World War, they experienced a boom and seemed to be able to do no wrong. Because of their absolute control and success, they were blinded as to what was taking place behind the scenes that would result in their undoing.

INDEPENDENCE

The move towards independent production started early. There were many wunderkind producers that worked at the major studios. Irving Thalberg was one such youngster who seemed to be able to do no wrong, producing hit after hit for MGM, but he died at a young age. David O. Selznick was another young, successful producer, and he was far more ambitious. He began his career during the silent period at MGM, and then moved to Paramount, RKO, and then back to MGM.

Selznick was confident in his abilities, yet resented the studios for profiting off of him. He decided he wanted to become an independent producer. He was not the first to attempt such an endeavor. United Artists was put together by a number of powerful industry players, including D.W. Griffith and Charles Chaplin, but Selznick’s vision was different.

Selznick founded Selznick International Pictures (SIP), and worked independently as if he were at a studio, yet he was aligned with the studio system. He would produce “A” pictures, choosing top-flight directors, actors and crew without the constraints and meddling of the studio chiefs. He had an obsessive personality and would micro-manage the projects. In many respects, he was at least partly the auteur of his works. Years later, Alfred Hitchcock would do his editing within the camera in order to maintain some sort of creative control of his pictures made with Selznick.

Selznick has his critics, but he was undeniably successful. He released a string of hits, notably A Star is Born, Rebecca and Gone With the Wind. Winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards for the latter two in consecutive years.

Selznick was as successful a talent scout as he was a producer. He was particularly fond of finding leading ladies, such as Ingrid Bergman and Joan Fontaine. He also “discovered” Alfred Hitchcock as a director and brought him to work in the United States with a seven-picture deal. He would contract with them directly through SIP, and if he was not ready to make a picture with them, would farm them out to other studios. As his clients stars rose, so did their fees. Eventually Selznick would become exhausted by the intensity of movie producing, and would lend his stable to studios. He would charge them the going rate, pay his talent based on the contract, and pocket the difference. This amounted to millions of dollars.

ANTI-STUDIO LEGISLATION

During the 1930s and 40s, the Department of Justice was taking a close look at the studio system. They felt that the studios were using unfair trade practices when distributing films to theaters, leveraging their power to get the chains to take inadequate deals. The primary tactics that the DOJ frowned on were block-booking and blind bidding.

Block Booking was the practice of selling a block of films to the theater. This usually would consist of one or two A pictures that would be guaranteed to give them a profit, and a handful of B pictures that may not be as successful. The A pictures were rarely parceled out on their own. It made business sense for the studios because they wanted to find screens for all their pictures, but the DOJ correctly thought that this practice was unfair for the exhibitors. Blind Bidding is just what the name implies. The studios would sell pictures to theaters without letting them see the film. Sometimes this would happen before picture had been produced.

Anti-Trust Decisions: From 1938 to 1940, there were a series of decisions that limited block booking, blind bidding, and other unfair trade practices. The first decision in 1938 was targeted towards all eight large studios, while the latter decision in 1940 was limited to the five majors. The repercussions of these decisions actually benefited the studios. They had to cut back on B pictures and focus on larger A productions. Because of the film boom during the war years, this helped the studios as the large productions were overwhelmingly successful and profitable. Losing the B pictures helped them slim down their overhead.

Revenue Act of 1941: With an expensive war in process, the need for tax dollars rose. The Revenue Act was passed in order to impose high tax rates on people who were in the upper tax brackets. There was approximately a 70-80% tax rate for those earning $200,000 annually. Of course a lot of the stars in Hollywood, behind and in front of the camera, earned salaries of this magnitude. For instance, all three of the leads of Double Indemnity earned $100,000 for their roles. Under the Revenue Act, they would have to pay roughly $80-90,000 to the IRS.

The repercussions of this legislation pushed the talent closer to independence. Rather than continue to pay flat fees, the studios changed contracts so that the talent would get a percentage of the profits. This meant that they would be taxed as capital gains at a far lower tax rate. Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe was one of those first deals.

Olivia de Havilland Decision: The star actress wanted out of her contract and the studio was effectively holding her hostage, unable to leave for a rival studio. She sued successfully to get out of her contract. The ruling kept the studios from adding suspension time to contracts to keep them from being free agents.

Post-war DOJ Initiative: With the studios continuing to be unfettered by any government intervention, the DOJ wanted to move aggressively at breaking up the studios. The issue at hand was the amount of the control. The studios were by definition a monopoly, vertically integrated to control production, distribution and exhibition. The DOJ wanted to break these three pieces up.

INDEPENDENT FILMMAKERS

As contracts ended, directors wanted to follow the Selznick model and forge their own independent companies. Several famous directors took this route and released films under their own “studios.” Some of them were more effective than others. Some of the filmmakers would remain independent, while others would return to the studios.

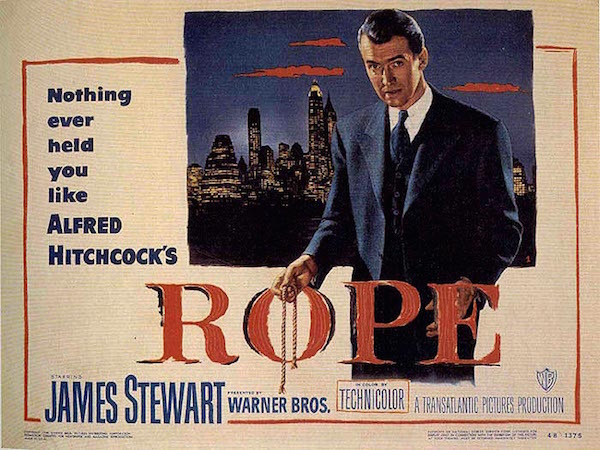

Alfred Hitchcock, reeling from his bad deal with Selznick, created Transatlantic Pictures. Under this company he made Rope (1948) and Under Capricorn (1949) with more creative freedom. Rope was more of an experimental film, and probably not one that would be possible for a filmmaker without Hitchcock’s caliber, and definitely not under the studio system. The experiment did not go as well as planned and was financially unsuccessful. The follow-up, Under Capricorn was less successful and that marked the end of the famous auteur’s independence. Hitchcock would make some of his best pictures in the 1950s for various different studios.

Frank Capra, William Wyler and George Stevens formed Liberty Films. Only two films were made through this company, and both of them were from Frank Capra. They were It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) and State of the Union (1948). It is difficult to believe given the reputation today, but It’s a Wonderful Life was a financial failure. This ended the project, with Paramount buying the assets and finishing the second Capra film. They also signed deals with the three principal directors. William Wyler made The Heiress for Paramount in 1949.

The most successful of these early director forays was John Ford’s Argosy Pictures. Ford had a lot going for him. For starters, he was reliable director, churning out quality content that did well at the box office. He was also an efficient director, usually coming in below budget. Ford did not strictly work on projects for his own company, working occasionally with the studios as needed, but he kept Argosy going for some time. Some of the notable Argosy films were Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Rio Grande, and The Quiet Man. Even with longevity and success compared to the others, a financial failure doomed his company and Ford also returned to the studios.

Next: The Beginning of the End

On the Waterfront: The Great Performances

“When you weighed one hundred and sixty-eight pounds you were beautiful.” – Charley Malloy.

“It was you, Charley.” – Terry Mallow.

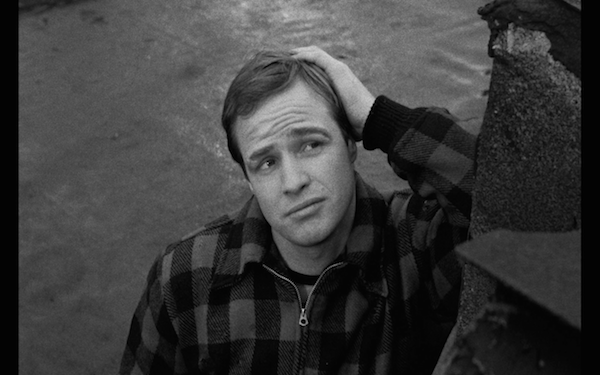

We’ll get to Terry (Marlon Brando) and Charley (Rod Steiger) soon enough, especially the famous scene from the image above. Even though that sequence is iconic and has one of the most memorable lines ever delivered in film, there is far more to the acting in On the Waterfront than any particular scene.

Kazan has often been described as an “Actor’s Director.” There’s more truth to that statement than many might realize. He began his directorial career in theater, but rather than stick to the traditional acting styles, he searched for something new and vibrant. He wanted something realistic that people could identify with. He drew from the Stanislavski System, worked with Lee Strasberg, and founded the Actor’s Studio in 1947. Many of the actors from this studio would become regulars in Kazan films, and many would subsequently become Hollywood Stars. The most notable, Marlon Brando, is considered by many to be the best actor that ever lived.

By 1954, Kazan had successfully implemented his acting system to the big screen. His greatest success was in adapting Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, which won three out of the four acting categories (Brando lost). That and other of his films were revolutionary when it came to the acting, but even Streetcar had a theatricality about it. Even though the acting was superb, it did not have the intense realism that was being imported from overseas, specifically Italy. On the Waterfront would change that, and Kazan considers it the one film where the final product was closest to his original vision.

In addition to Brando and Steiger, who were established method actors, there were other Actor’s Studio alums, including Lee J. Cobb, Eva Marie Saint, and Karl Malden. These performances all stand out, and all were nominated for Academy Awards, with Brando and Saint winning. The strength of the acting extends all the way down to amateurs and extras. Just about every human being in the film is convincingly real, whether they deliver one line of dialogue or several.

Johnny Friendly, portrayed by Lee J. Cobb

Cobb had worked with Kazan as Willy Loman on stage in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. He was no stranger to the method and could play a variety of characters. He would have quite a career. He is often overlooked for his work as Johnny Friendly, but that is mostly based on the strength of his co-stars. He is the ideal villain. While he does not show the same humanity that Terry and Charley show, we understand that his fiery, combative motivation comes from a sense of self preservation.

Johnny probably did not always come off as the villain. We get a sense in the early scenes that he was a mentor for the Malloys when they were kids. That may have been based on his own self-interest of indoctrinating them into the system, casting favor onto them so they would remain loyal and not “squeal,” but all the same, the hostility Terry would feel toward him was likely a new development. Johnny would remind them where they came from, but he also expected them to do his bidding without question. If someone crosses him, they were gone. It could be something as small as getting a money count wrong (which implies stealing) or worse, talking about their operation to the commission.

Cobb’s performance is nuanced to a degree, in that we see him calmly giving out orders, maintaining his composure under some pressure, while we also see him in a state of fury and rage when the situation calls for it. The ending confrontation between Johnny and Terry is legendary, with an amazing, explosive exchange between both actors.

Father Barry, portrayed by Karl Malden

Terry Malloy might be the protagonist of the film, but Father Barry is unquestionably the “good guy.” He is a local Catholic priest who exhibits real concern and passion for the people who are being taken advantage of down at the docks. Rather than play the priest in stereotypical, solemn fashion, he strikes a balance between Barry’s obsession toward righting the wrong, and even his toughness by standing up to the organized local that he knows has been guilty of terrible crimes including murder.

When he is talking to the dockworkers, especially Terry Mallow, he is understanding of their fears and concerns, while also taking upon himself to get them to take action. He uses religion when needed to prove his point that acting against those in power is not only in the people’s interest, but is in God’s interest as well. When Terry Malloy tells him, “If I spill, my life ain’t worth a nickel,” he quickly retorts, “How much is your soul worth if you don’t?” Most importantly, he is not afraid for his own well being, and in this respect he is one-sided, but Malden adds as much dimension and tenacity as he can.

Edie Doyle, portrayed by Eva Marie Saint

Brando tends to get credit for the great performance in the film, but his work was enhanced by the great work of the people he acted with. Saint was a newcomer to acting, but she had also been educated via the Actor’s Studio. She was also personally similar to her character. She was a scared, inhibited, naive 19-year-old.

Edie is a fragile character, still dealing with the loss of her brother, while being pursued aggressively by Terry. She is reluctant to open up, partly due to her sensitivity with the loss fresh in her mind, but also because of her reservations with Terry’s favored position by the locals in power. She becomes embroiled in the quest of Father Barry and the confidence of Terry Malloy, who is torn as to what he should do. Through her performance, we understand Saint’s manic reaction to what is going on around her. During the wedding scene, she is literally crying at one point, and tentatively dancing with Malloy moments later. Her performance is magnificent, and she helps endear us to both characters, making them more sympathetic.

Charley Malloy, portrayed by Rod Steiger

Rod Steiger has been accused often of over-acting and being hammy. I touched on that to an extent when reflecting on Jubal. He does the same thing on occasion in On the Waterfront. He plays Terry’s brother Charley, who is a ranking member of the union mob.

Most of the time Steiger stays in the character of the henchman and trusted man of Johnny Friendly, fighting his battles, even if those are against his own brother. At times he is quietly obedient to his boss, while at others he would raise his voice and thunderously bash someone who either does not conform to the system or rejects it. He is a company man, through and through. Steiger is excellent in the role, one of the few times I think he has shown his true potential as an actor (the other is The Pawnbroker, which should have landed Steiger an Oscar).

While Steiger has many bright moments, he was at his best during the cab scene. I’ll come back to that momentarily.

Terry Malloy, portrayed by Marlon Brando

I consider Marlon Brando’s performance in On the Waterfront to be the greatest of all time. Some have dismissed him of basically playing a mumbling, gum-chewing buffoon, but that’s part of the strength of the performance. He is a buffoon, but so is Terry Malloy, a former prizefighter with barely any education. Brando is completely realistic in the role, using the vernacular of the waterfront and fitting in with the locals, many of whom were extras that actually were Longshoremen.

Brando is not only engaging and entertaining to watch, but he also carries the personal nuance and sensitivity that his character needs. We need to believe that he would be respected by the mob, yet also they could be afraid of him and what he knows. We need to believe that he is charming enough to lure Edie to his side, while also sensitive enough to not scare her away. We need to believe that this is a man who used to knock people out for a living, who now works at the docks, yet spends his spare time caring for pigeons on a rooftop. The audience has to like the character as much as Edie and Father Barry do, and we have to rally behind him in order to make the plot and ending work. He has to become the underdog.

Brando puts on a clinic with method acting. Yes, he does chew gum. He fidgets and plays with his hair, but these are all things that normal people do. That’s what Kazan was going for. He did not want someone like Ralph Richardson or Laurence Olivier (both fantastic actors, just different). He wanted someone who could act naturalistic at and around the docks. Using props, gestures and body mannerisms was one of the ways Brando would keep himself on his toes. He needed to be distracted enough in the scene that he could be convincing at being the person, and not just enunciating some previously written lines. His performance has the feeling of an improvisation, and some of the best moments come from material that he and his co-stars previously improvised.

The courting scene between Terry and Edie is a classic, and is notable for the use of the glove. She drops her glove while he is trying to talk to her. He picks it up, plays with it, and eventually puts the glove on, hinting at some sexuality. By this action, with her personal belonging invaded, she gets a little more comfortable and closer to him. They are connected with that glove. When she takes it back at the end of the scene and puts it back on her hand, she is a changed woman and the relationship has made progress.

The glove scene came out of an improvisation during rehearsal. She dropped the glove and Kazan let them keep going. Many directors would have stifled this creativity, but the actors made it work and Kazan used it in the completed film. It is one of the most memorable scenes in the film.

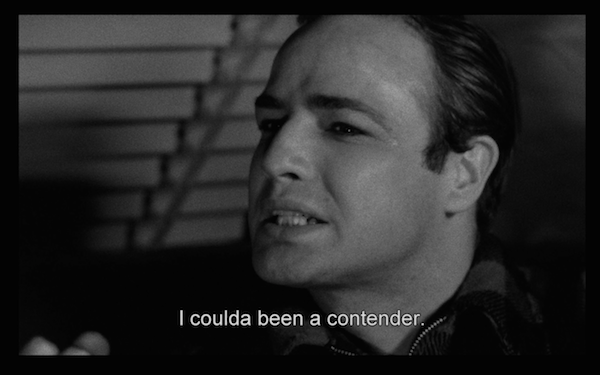

The Contender

If you haven’t seen On the Waterfront, you’ve probably heard of or seen the infamous cab scene and the “Contender” line somewhere before. I’ve seen the movie about 3-4 times, but I’ve seen the cab scene easily a dozen times, maybe two dozen, and it gets to me every time. Even though it stands alone as an exceptional scene, it is the culmination of the performances up to that point that really makes it special.

We learn through dialogue and exposition that Terry used to be a boxer, but that his career ended because he had to take a dive. We do not learn the caliber a fighter he was, or the perspective of Charley until the cab scene.

The scene begins with Charley trying to talk some sense into his brother. He doesn’t want him to testify at the commission. When he makes little progress, he uses violent manipulation, probably the same way he has used it many times before. He pulls a gun on his brother and demands that he take a comfortable job in exchange for his silence. This is where Steiger’s propensity for big acting really works. When Terry refuses and Charley realizes that he might testify, things get heated. The performance reaches an unexpected point of tension when the gun comes out. The way Brando reacts is touching. Rather than cowering in fear or getting defensive, he just shakes his head, says his brothers name, and slowly pushes the gun away. He is not angry, just disappointed.

From there, the situation completely changes and the brothers are on even footing. There’s no way that Charley could kill his brother, and him pulling the gun was as empty a threat as he could muster. The scene picks up in this YouTube and this is where the magic really begins.

Even though the “Contender” line is the famous one (#3 on AFI’s Greatest Quotes list), there are another four words that really cut to the heart of the matter and are the most affecting. “It was you, Charley.” They reminisce about old times. He talks of Terry when he was 168 pounds and beautiful, how he could have been “another Billy Conn.” Charley blames it on a manager. No, “it wasn’t him Charley, it was you,” Terry says.

From there the speech happens.

I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I could’ve been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am. Let’s face it. It was you, Charley.

Brando delivers the speech with gusto, with passion, with precision. Terry has been waiting ever since that fateful night where he took the dive and lost his shot, feeling resentful towards his brother the whole time. He does not overact here. He does not scream with rage. His words are those of disappointment, of dejection. His dreams were shattered, and finally he can express himself to the man who crushed them, all to make a quick buck.

The rush of passion is gone when he says “It was you, Charley.” The line is delivered with just a feeling of shame for his brother, that he was so short-sided that he ended a dream.

Steiger does not get the credit he deserves for this scene, but the way he reacts is just as important to the scene as the way Brando delivers the dialogue. The way Steiger is silent and expressionless as the words hit him enhances the scene. He is clearly affected by the remarks his brother has made, and immediately changes direction, which seals his fate. He loves his brother and realizes that it was him. There is no overacting here, just acceptance. “Okay, okay,” he says. That’s it.

Through these few minutes, we have someone pulling a gun on his brother, and then just moments later, giving the gun up and sacrificing himself out of love. We see a brief glimpse of Charley, the authoritarian figure, when he barks at the driver, “You, you pull over.” The rest plays out as it has to.

Having seen the scene so many times, it is difficult to put into words how meaningful and memorable it is. The only way I can describe it is beautifully tragic. It is pure power. Brando and Steiger, through Kazan and a makeshift set, made one of the highest points of American cinema in a matter of minutes. It is still remembered vividly 60 years later, and will continue to be remembered as a key part of cinema history.

Jean-Pierre Melville’s Resistance

“This film has no pretension of solving the problem of Franco-German relations, for they cannot be solved while the barbarous Nazi crimes, committed with the complicity of the German people, remain fresh in men’s minds.” – Le silence de la mer

The above words are the opening statement from Jean-Pierre Melville before his first film about the German occupation of France during World War II, Le Silence de la mer. The words represent his anger, and would color his other two films about the resistance. His take on the occupation is pointed, caustic, tragic, and in many instances he does not pull his punches, accusing both French and German alike of misdeeds.

Jean Pierre Melville came from Jewish ancestry, and grew up “in a cultured, bourgeois-Bohemian environment” (Vincendeau). He was fond of American culture, and even changed his surname from Grumbach to Melville in honor of American author, Herman Melville. He served in the military and participated in the French resistance, but details are scant as to what specifically he did. He has revealed little about his activities, and we can only speculate as to the level of autobiography in his later films, although it is clear they are based on his own experiences.

Melville became a cinephile at a young age, and during the 1930s he consumed cinema from morning to night. He claimed to go to the cinema at 9am and leave at 3am, immersing himself completely in the world of cinema. Classical Hollywood and American culture influenced him to the point that “for most of his adult life he wore a Stetson hat and dark glasses, and smoked large cigars” (Williams). Despite his obvious appreciation for all things American, he was also entrenched in the French film culture, among others.

Politically, Melville was an enigma, but he has admitted to being a communist from 1930 to 1939. Afterward, he became a “right wing anarchist” according to his own words. His films show some of these political images, albeit still with some ambiguity. His resistance films are similar in fashion as many of the left-wing films of the 1930s. His gangster or noir films are less political, but you can see a hint of his anarchic philosophy.

His career began in rebellious and anarchic style, with him filming without permission from the unions. He used unconventional methods, such as small crews shooting entirely on location. This would begin his career as a filmmaker in radical fashion. He would produce his films independently and eventually from his own studio, establishing himself as an outsider in the post-war French cinema scene.

La Silence de la mer

Melville’s first film shows resistance in a subtle and quiet form. During the war, a German occupying officer imposes on an uncle and niece’s house for lodging. As they live together, he tries to engage the pair in friendship and conversation. He loves France and its culture, and is blinded by the atrocities committed by his side during the war. They resist by not speaking to him, barely even acknowledging his presence. That he turns out to be a likeable and benevolent person is irrelevant to their resistance, and despite his efforts, they do not break their silence throughout the entirety of the film.

Unlike many of Melville’s later American-style gangster films, this one was in familiar, French film language. Even though having two main characters hardly speak during the film was uncommon for the time, the tone is similar to the later 1930s darker poetic realism. At first it appears the guest is a foreboding, evil German and his hosts are unflinching and condemning. They have an arc that reveals that they are not as unflinching as they intend. The German has some admirable qualities, and charms his hosts to a certain degree. They emote differently during their later, friendlier encounters. Despite their change in expressions, the French pair do not ever speak.

These multifaceted characters are not dissimilar to Marcel Carné’s characters in Hotel Du Nord and Port of Shadows, who are endearing despite their flaws. Another example is how officers from opposing sides find common ground in Renoir’s Grand Illusion. If Melville’s characters would not have parted, they may have eventually broken their silence and found mutual, common ground.

What is striking about the film is that Melville is glorifying the German character, and in a sense, indicting the French. By ignoring his overtures, they do themselves and their cause a disservice. They make no progress and live in discomfort for the entirety of the officer’s stay. The resistance in this case is fruitless and unnecessary. The same could be said with the actual resistance, which would in many cases prove divisive and counterproductive. Melville likely saw this lack of progress in person during his own experiences, and his shift away from communism to the right during the war was probably rooted in what he saw and observed as a member of the army and resistance.

Léon Morin, Priest

Of Melville’s resistance pieces, Léon Morin, Priest is the least aggressive and political. The resistance itself is more in the backdrop, as the plot is about a moral, sexual and spiritual exploration between a single mother named Barny and Léon Morin, a Catholic priest. He directs her towards Catholic teachings without directly trying to convert her, yet eventually and surprisingly, she converts on her own, perhaps to protect her daughter who is in hiding, and because of her romantic attraction to Morin.

Even though it does not make an overt statement about the resistance, there are a few subtle hints. One example is that her daughter is Jewish and named France, and she is sent away to avoid persecution during the occupation, only to return when the Germans leave. Other examples are in the dialog. When arguing with a co-worker about collaborating versus resisting, she says, “Better that France die than live in mortal sin.” Resistance efforts are often mentioned in passing. In one instance Morin mentions the bombing of a building, which Barny walked by without noticing. There are several areas where it could be argued that Melville is making statements about the resistance, such as Barny’s conversion – possibly she is converting to the resistance and away from collaboration.

Again, the film language here resembles 1930s poetic realism cinema. The quiet emphasis on character under the cloud of resistance recalls some of the gloomy late 1930s darker pictures. The story is dialog driven with little action, unlike other mainstream resistance pictures. The relationship between the two leads is high on drama, romanticism, poetry, and reality. Léon Morin, Priest was released in the midst of the French New Wave period, and the leads were both famous from New Wave films, yet the film had less in common with the films of its time and more in common with pre-war films.

It is also worth noting that Barny is communist, which Melville decidedly was not at the time, although there may (or may not) have been some lingering sympathies from the time that this was set. Since he had reformed, there is a chance that Barny’s transformation and conversion was a mirror of Melville’s change in political beliefs.

At first glance, the film is not as anti-French as Le silence de la mer, but there are some mixed messages. Melville is clearly pro-resistance, as expressed in Barny’s argument and by Morin’s actions and sympathies towards the Jewish, yet he is not as clearly pro-French. By Barny sending her daughter away, he could be implying that the real France is absent during the resistance, influencing Barny’s spiritual crisis. There is also the matter of Barny’s workplace and the contrast between resisting and collaborating. The fact that prominent characters are collaborators reopens some old wounds.

The biggest indictment and most surprising given Melville’s American influences is near the end of the movie after the Germans have left. The Americans have taken over, and two of them try to sleep with Barny. While they may be the French saviors, they are hardly morally superior to the Germans. After they leave, Barny’s daughter France asks “Are they Germans too?” Melville might have loved American films, but that did not mean he loved American soldiers in his homeland after the war had ended.

Army of Shadows

Of the three Melville resistance films, Army of Shadows is by far the most ambitious, the most personal, and the most highly regarded. It is the story of a resistance cell, mostly from the perspective of Philippe Gerbier, one of the upper level members. The character is allegedly a composite of people Melville actually knew. The story begins with his jailing and escape, and follows along his further adventures as an active member of a resistance group. It ends with the death of virtually everyone in the upper echelon of the organization. The film is both an adventure and a tragedy.

This was one of Melville’s final films, and was an outlier compared to his productions in this late era. Aside from Army of Shadows, his films were exclusively highly masculine gangster film. Like his previous two resistance pieces, this film had some dark minimalism, which was also present in some of his gangster films. The remnants of poetic realism and most other French influences were for the most part discarded in favor of American and English (primarily Hitchcock) crime films. The realism within the movie has less to do with the 1930s, and more to do with Melville’s personal experiences, including his hero worship from the time. His earlier, realism films countered the idea of resister as hero, whereas this film embraces and perpetuates it.

The message in this film is not subtle — the major players in the resistance were courageous, undeniable heroes, but that it was ultimately a waste of efforts, as it cost more lives than were saved. The fates of his main characters punctuates that the resistance was an unspeakable tragedy. While he does not place blame for the futility of the movement, it is hinted that the lack of organization among movements and the hesitation of the French populace to take sides doomed their efforts. Much of the time spent by the resisters in both the film and history, was in rooting out and executing traitors.

The evidence of Melville’s goal with this film is in what he changed from the source material. Ginette Vincendeau notes that Melville “changed the novel to a different vision of resistance characterized by misery and destruction.” She also notes that unlike the previous two resistance films, the Germans in Army of Shadows are unequivocally evil. There are no redeeming values or morality within any of them. Like with Melville’s gangster films, they are portrayed as the bad guys and are flat characters.

Even though more than 25 years had passed since the war ended and this film was produced, Melville’s personal experience screams at the viewer. His anger had not subsided. It is mostly directed towards the Germans, although the French are not unscathed. They are held accountable for incompetence, and they are often shown as collaborators who thwart the heroes. The key example is when Gerbier commands Mathilde to not carry a picture of her daughter with her. Mathilde disobeys and this is the one action that results in the undoing of the entire operation.

Conclusion

Melville spoke from experience when he made his three resistance films. His first resistance film was close enough to the war that the memories and emotions were still raw. This was both a cathartic and a career breakthrough for him. His second resistance film was a way for him to passively process the spiritual and moral dilemma that encompassed not just him personally, but the entire French people during the time. His final piece on the subject was by far the most autobiographical, the most personal and the most damning of the cause as a whole. Enough time had passed that he was able to tell the tale from a distance, using the American film style that he had become accustomed with. Even with the years in between, his anger towards the entire experience is palpable.

There were many filmmakers that addressed the resistance, including Louis Malle, Claude Chabrol, René Clément, Francois Truffaut, among others. While all of these filmmakers lived during the war and had personal experiences and emotions, they were not as deeply involved in the activities as Jean-Pierre Melville. Like many of them, he became a highly skilled director and had a way of expressing his experiences and ideals through film. As a result, his resistance films, particularly the first and last, are among the most profound and memorable on the subject.

Works Cited

Hayward, Susan. French National Cinema.

Phillips, Richard. World Socialist Web Site.

Vincendeau, Ginette. Jean-Pierre Melville: An American in Paris.

Williams, Alan. Republic of Images: A History of French Filmmaking.