Blog Archives

The Merchant of Four Seasons, 1971, Rainer Werner Fassbinder

If you can say one thing about Fassbinder’s films, you can say that he was adept at portraying and processing human feelings. These were usually negative human feelings. For example in The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant, he explored vanity and loneliness, whereas in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, he explored isolation and rejection. There are many other examples, such as Fear of Fear, which is a lesser-known Fassbinder that captures anxiety better than any film I’ve ever seen. With The Merchant of Four Seasons, the emotion that he captures is depression.

I’ll be honest that depression is something I don’t understand. Sure, I’ve had bad days and been down in the dumps. Who hasn’t? I’ve known people that have been depressed, and I’ve had a tough time connecting with them. One friend sent me this cartoon link from Hyperbole and a Half, which helped me understand depression to a certain extent. I can never understand it as well as people like this friend or (likely) Fassbinder experienced it, but a film like The Merchant of Four Seasons gets me closer.

As fair warning, this is a film that requires spoilers to discuss properly. If you haven’t seen the film or are spoiler sensitive, then I would not read this entire post.

The character of Hans is a disappointment to most in his life. When he returns from the military, after finding out that someone else did not make it home, his own mother says, “the best are left behind while people like you come home.” We learn later that his military career ends with a sexual transgression. He then becomes a cart merchant, peddling fruits for a small profit in order to support his wife and daughter. When he isn’t working, he drinks with his friends and does not want to be disturbed. In one pivotal scene, when his wife Irmgard (Irm Hermann) demands that he come home, he throws a chair at her. Later, when questioned, he beats her.

His family scorns him and thinks of him as a disappointment. They shun him after the case of abuse, siding with his wife while he beckons her to come back. The only person in his corner is his sister Anna (Hanna Schygulla), yet she has a minor role and is mostly ignored. When we see the family on screen, they serve the purpose of reminding us how worthless Hans is in their eyes. It’s no wonder that he feels such helpless despair.

Hans suddenly has a heart attack, and is forced to stop drinking and is not allowed any heavy activity. Given his prior anguish, one would think that this would push him further into depression, but the opposite happens. He takes on the role of proprietor, hires a productive employee, and enjoys profits. In a later scene, his family is surprisingly pleased with him. In their eyes and his, he has succeeded as a cart merchant.

Things come tumbling down due to another theme among the primary characters – weakness, especially in terms of their sexual proclivities. Han’s weakness with an admirer is what ruins his military career. In an early scene, he delivers fruit to an woman and is chastised by his jealous wife for spending seven minutes with the woman. We learn later that there is a hint of an affair happening at some point, which possibly happened off-screen during these early scenes. While in the hospital, Irmgard has an affair of her own with a taller, more masculine man. That man coincidentally ends up becoming Hans’ successful salesman. In my opinion, this was too coincidental, but it was a necessary plot development to take Hans further down in his slide.

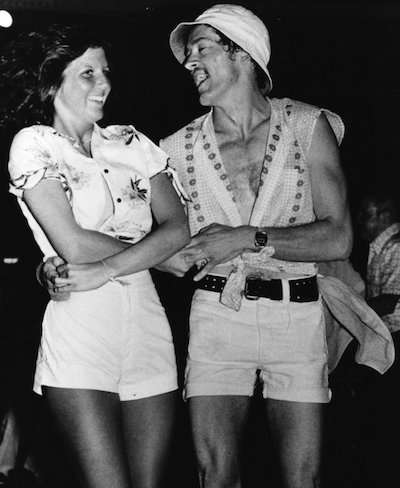

Irmgard is a confounding character. She rekindles her relationship with Hans, even when he is employing her former, temporary lover. It is in this period that his depression begins to take shape again. Even before he discovers the truth, which comes up after he catches him skimming money from his sales, a strategy in which Irmgard suggested. She is the mystery. Fassbinder usually portrays women as strong and sympathetic characters, but Irmgard makes some baffling decisions. At times she seems to want to undermine Hans, while at others, like in the image above, she is saddened by his downfall.

Hans’ depression reaches such a low that he decides he wants to die. We learn through flashback that this is not the first time he’s reached this low of a feeling. When being whipped by an enemy soldier, he faces certain death, only to be rescued at the last minute by fellow soldiers. Rather than thank them, he asks them, “why didn’t you let me die?”

The final drinking scene is the culmination of the burdensome weight of all those who he has disappointed, including himself. Because of his health condition, he holds the gun that will decide his fate. He commits his suicide with bitterness and no regret. He even dedicates each shot to a certain someone who has wronged him. This is his way of getting back at the world.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements

Commentary – Wim Wenders, 2012.

Wenders talks about how it is unusual to comment on a film from a friend and colleague that died 20 years ago. He gives a commentary you would expect from Wenders. He speaks slowly and relaxed. He is not the type to comment or analyze every little scene. Even though I like analytical commentaries, I also like this type because it is more like you are watching the film from a friend.

- Fassbinder did everything himself, including writing, directing, sometimes acting, editing, sometimes producing. Working on so many projects as Fassbinder did required him to be working on the next one while he was finishing the last one. Wenders says that the speed in which he worked would eventually kill Werner.

- Wenders loves film, and he especially loved Hans Hirschmüller so much that he cast him in Alice in the Cities.

- He had such a strong ensemble that he would often cast his major actors in small roles. Hanna Schygulla and Kurt Raab are examples here. Of course Schygulla, in Wenders words, would “become one of the major stars of German cinema.”

- Back then, selling fruit off a cart was a real Bavarian profession. He points out the fact that the people speak with a distinct Bavarian accent, but that does not come across with subtitles.

- Prior to the German New Wave, the most successful German films were either Westerns or softcore porn. This direction into character-based melodramas was a major shift. They learned their craft from American films.

- He talks about the New German Cinema experience. They were not in each other’s way, had nothing in common, different perspectives, different missions. They helped each other, had no envy, shared cast and crew. Fassbinder was way ahead of them. By this time, Wenders had only made two short films. They were not bound by a cultural aesthetic, and never discussed content, style, but more about distribution, projects, etc.

Irm Hermann: 2015 interview.

She had no formal training, but got lucky when she met Fassbinder and he pulled her off of an office desk and put her in front of a camera for The City Tramp. He quit her job for her. Fassbinder was charismatic and started in the theater. She had no training save for how Fassbinder trained her. She didn’t want to do the sex scene, but Fassbinder was discrete and sent everyone out of the room. She is grateful for the film because of the Douglas Sirk-like close-ups. Her and Hirschmüller won German Awards, as did the film. and that was a major deal.

Hans Hirschmüller: 2015 interview.

The role of Hans was written with him in mind. Fassbinder wanted someone down to earth and simple, which was really what he was at the time. He knew the types of merchants that he would play. Fassbinder didn’t tell him anything about the role. He just made him read the script, and asked if he approved.

They did not often do multiple takes. Usually one or two, sometimes three, but very rarely four. Rehearsal is when they would improvise, never during the scene.

It was a tough role for him because he had to face death like he never had in his personal life. He had trouble getting to the position of being helpless. The scenes where he was depressed were the toughest for him.

Eric Rentschler: Interview with film historian and professor at Harvard.

This was the film that put Fassbinder on the map. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive. Some said it was the best film to come out of Germany in years. Fassbinder had been working productively prior to this, but his rise out of Merchant was meteoric. Early films were bleak and resembled neo-noir. You could tell that Fassbinder was a student and fan of film.

Fassbinder is good at showing what character’s are capable of, both good and bead. Irm Hermann is an example of this because she has adultery and is planning on leaving her husband on one occasion, yet adores him in other occasions.

The film was based on his uncle, who had fallen from a high position and ended up as a fruit salesman.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

Ride the Pink Horse, 1947, Robert Montgomery

I’ve talked before about “regulated differences” before when discussing La Promesse (link) by the Dardennes. When looking at a film noir, the theory still holds weight, or if anything is more relevant. By 1947, noir was starting to be thought of as a genre (would more accurately be called a “cycle”) thanks to the French critics like André Bazin. 1946 had been a watershed year for noir with The Big Sleep and The Killers pushing the boundaries, but there were still a great deal of constants. The protagonists were almost always confident to the point of cockiness, and aside from angst, frustration and confusion, would rarely show emotion. Their characterizations were often stoic and rugged, with a heavy dose of masculinity. Even they often were fallible, naïve, and subject to being bamboozled by femme fatales, they still rarely showed softness or humanity.

We appreciate the two noir films I just mentioned because they are inventive with plot structure and narrative, but they still hold true to the conventions. Ride the Pink Horse begins by staying within these conventions, yet at some point things start to crack. The façade fades, and we see weakness. The protagonist ends up losing control, becoming a shell of himself. He is so weak and incoherent that he is helpless to resolve his plotline, much less even comprehend how far he has fallen. That is Robert Mongtomery’s take on noir. While it does not measure up to the best of the genre, it is worthy of respect and admiration for showing a different and unique facet. This weakness and humanity is one of several regulated differences within the film, but it is the cornerstone of the structure. It is existential in this regard. Some things are just out of our control, yet we try to persist.

Robert Montgomery acts and directs, and through both he brings a distinct sense of style. He uses lengthy takes, gives the scene some breathing room for events to unravel. As an actor, he begins with the custom, stoic characterization found in noir films. He is emotionally and personally impenetrable, working only towards the goal of avenging his lost friend Shorty. He believes Shorty was taken down by the suave and charismatic war profiteer, Frank Hugo, who is in a class amongst himself and lords over the poor town of San Pablo, Mexico.

When Gagin arrives in San Pablo off of the bus, he is stern and forthright. He walks into the train station and walks out, sizing the place up without an expression on his face. He means business. Later he encounters two women that welcome him with a certain wanting. They are more attracted to the fact that he is a well-dressed American, but he picks up on their ruse and rejects them. Instead a younger, shy Indian girl catches his attention. He asks for her to direct him around town not because of any attraction, but because she is non-threatening.

Later he befriends a local Mexican, Pancho, who becomes his caretaker and friend. Pancho calls Gagin “The Man With No Place,” and opens up his house to the stranger. They become fast friends, and creaks start to show in Gagin’s impenetrable resolve.

“The Man With No Place,” is an appropriate label for a lot of noir lead characters. Many noir films feature private detectives as the protagonists, but deep exposition is not usually necessary. They are almost always hard-boiled, and revealing why would shatter the mystique. The assumption is they have become so tough because they’ve seen so much trouble that they are now jaded towards the world. We learn very little of their origins or backstory. Can you imagine Sam Spade talking about daddy issues when he was growing up? It just doesn’t happen. We learn about the characters and their motivation as they interact with other characters.

That’s why I love the label of “The Man With No Place” for Gagin. We know next to nothing about where he came from. We know he arrived in a bus and that his motivation is revenge for the loss of his friend, Shorty, but that is it. As a character, he has no place. If he makes it through this mess, we have no idea where he’ll return to or whether things will improve. We do learn about his feelings toward the world based on his interactions. For Gagin, we learn that he favors the lower classes and even a government investigator over the upper classes. Based on his dress, this is an unusual mindset since he has an upper class appearance. That is why the girls took notice of him early on. We do not know why or how he became to despise the rich. A good bet would be whatever happened to Shorty, but since he is “The Man With No Place,” this does not need to be explained.

Frank Hugo and Pancho have a couple things in common. First of all, they are both charismatic and personable. Even though Hugo is not trustworthy, he does lure you in and at times is a likeable character. Pancho is a delight, and Thomas Gomez was rightfully nominated for an Oscar for the portrayal. He is as benevolent as they come, and just lives to enjoy life. The key difference between him and Hugo are not just the class they occupy, but their feelings towards money and consumerism. Hugo cannot get enough money and power, whereas Pancho has little care for money or material things. Gagin identifies and appreciates Pancho’s values, but he is squarely in the middle. While his resentment of the upper class machine is palpable, money is part of his motivation, probably as a means of self preservation. In one scene he even tries to cut Pancho in for $5,000, which he sees as a gesture of friendship, but turns out to be one of ignorance. Pancho could care less about $5,000.

Another way this diverges from the traditional noir is in how it handles the femme fatale. In many noir films, the femme fatale has a bit of irresistibility and the hero cannot help but fall for her charms. This time, Marjorie Lundeen fills that role and appeals to Gagin, trying to lure him with both her looks and the potential for money. Her motivation is the same as most noir females. She is not on Gagin’s side and will double cross him anyway. He rejects her categorically. A significant scene where this is demonstrated is when he takes Pila to dinner. At first she seems out of place, even remarking on how unusual it is to eat a fruit cocktail. Marjorie approaches during the meal and asks Pila to step aside so the grown ups can talk. Pila, obedient as ever, obliges. Gagin hears out Marjorie’s offer, but inevitably sends her away for the lower class and more demure Pila.

Things do not go as they planned, and violence ensues. One location that I have not mentioned, yet is important to the plot, is the titular Pink Horse. This horse is part of a carousel, which is where the lower classes and especially children take pleasure. Pancho identifies more with this group, and young Pila belongs to both of them. This carousel is also important because it is where Gagin first shows humanity, where he cracks a smile while watching a girl ride.

There is a fantastic scene where a violent action is taking place in front of the children in the carousel. We see very little of the violence, but instead see the anguished reaction on the children’s faces, and this includes Pila. This object of base pleasure becomes desecrated with violence by the powerful, which is just another example of how unfair and unequal life is in this small Mexican town.

I will spare details from the ending of the plot because it is quite an experience to watch on your own. I will say again that things work out differently than most noirs. The lead character becomes impotent in his fight, and must rely on the help of his friends. By this point his character has transformed from the hard-boiled and stereotypical noir hero to a needful victim.

Tonally and thematically, the film is all over the place. At times it is pure noir, with dark shadows and shady characters. At others it is rosy and uplifting where the sun is shining brightly. The lengthy opening scene has both attributes. The sun is shining, but Gagin has his own personal shadows. Over time, his personality changes and the landscape varies from the confrontational Hugo apartment to a festival. These tonal changes are a welcome change from the noir template, as they develop not only the characters, but they give the film an identity that separates it from dozens of other noir pictures.

Film Rating: 7.5/10

Supplements

Commentary with Alain Silver and James Ursini: These are Film Noir historians.

Robert Montgomery was instrumental in breaking the barriers between actors and directors. He was one of the first who had gone from acting to directing and achieved success.

He had a unique style. For instance he uses long takes, notably with the intro shot, which give an added level of suspense and more of a sense of place. Montgomery learned a lot of technical tools from John Ford, who was his mentor. With this film he was parodying noir stereotypes. He does not cut unless he has to. There are not many point of view or reaction shots unless they are absolutely necessary to say something.

Pila is surrounded by some mysticism, most of which comes from Native American stereotypes. She sees him dead and makes a comment about him being knifed. She also is a major factor in getting Gagin to change. One of the commentators says this is a “movie is about reformation, redemption in many respects.”

The restaurant scene is important for many reasons. For one, there are elements of romantic comedy between Gagin and Pila, and then it is interrupted by Marjorie and it switches back to noir. Gagin’s reaction to her, as well as all the other people ijn the restaurant that give him looks, is a reference to his hatred of the snobbishness amid the upper crust of society.

In Lonely Places: Interview with Imogen Sara Smith, author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City.

Noir is not a genre. It is about mood and themes, interiority, psychology and motivations. There are many classic noirs set outside of the city, which is Smith’s study topic. Detour is one example of many in America, while Touch of Evil is an example of Mexico.

Mexico is important for noir because it is a place people escape to. It is used often and is portrayed as transient, lawless. Unlike other Mexican noirs, Ride the Pink Horse pays a lot more attention to local people and their culture rather than just on other Americans.

Dorothy B Hughes, the author of the book that Montgomery adapted, was interested in characters, environments, class, and how these influence development. We see a fiesta in the movie, but the novel has a lot more detail about fiestas and Mexican rituals.

Smith calls it an anti-noir. She concludes that is opposed to most noirs. It can still be categorized as a noir, but is more optimistic.

Radio Adaptation – More of a novelty. I’ve said this before, but this is the type of thing that I wish they would let you take with you. I listened to the first 20 minutes or so, and found it enjoyable as they recreate the action of the movie, but of course it pales in comparison.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

Les Blank, Always for Pleasure, Part Three.

GARLIC IS AS GOOD AS TEN MOTHERS, LES BLANK, 1980

In my opinion, the best filmmakers are the ones that continually challenge themselves. Too many get comfortable making a variation of the same film repeatedly, with diminishing results. While Les Blank’s early documentaries that centered on Louisiana and Texas were brilliant, he was wise to move along and venture into new territory. While the results were not always as good as his best early work, he had a way of picking fascinating and unusual topics.

He ventured north and west for his take on … you guessed it — garlic. He uses song to set the stage for this wacky documentary, with the lyrics “Garlic is the Spice of Life … Add Garlic in your Life.”

The subject is northern California, where there was a burgeoning garlic culture. He uses a similar format as his Louisiana films, most notably Always for Pleasure, to explore the culture, geography and finally the process of producing garlic.

My primary quibble here with Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers is that it focuses a little too much on the culture and less on the production, which unfortunately is reduced to a few minutes toward the end of the movie. Blank could have interspersed images of the production as he did so successfully with his earlier cultural and musical films. He has an eye for making something ordinary like food production look extraordinary. Instead, the culture dominated much of the early part of the feature. He shows people like the gentleman in the image above, people who think that garlic has spiritual or aphrodisiac powers. One guy even mutters that if you eat enough garlic, you’ll feel high. Some of the culture elements seem to be exaggerated to make them seem as grandiose as Mardi Gras culture in New Orleans, which of course is ridiculous.

He struck the appropriate balance with food. Les Blank just cannot fail at showing great food and making us hungry, even if it’s for the so-called ‘Stinking Rose.’ Some of the finest scenes were when people were preparing and cooking dishes with garlic. The scenes of Bastille Day at Chez Panisse restaurant are some of the best in the movie, where chef Alice Waters dedicates the day garlic-themed dishes. Near the end she makes a delectable version of chicken pot pie packed with vegetables and, of course, loads of garlic.

This was a good attempt for Les Blank to relocate his style on a fringe, niche culture. It was my least favorite of the set so far, but it had potential, and I can tell from a later film that it was useful as a stepping stone.

Film Rating: 5.5/10

Supplements

For the Love of Garlic: – This was a 2014 re-visitation with the people involved, including Alice Waters and Maureen Gosling. They talk about how much Les Blank loved garlic. He would keep it in his pocket and shave it into his food. Waters reveals that after seeing the film later, she realized that she was not cooking the chicken dish correctly. Gosling talks about how they inserted the cultural content before the production deliberately, which I think was a mistake. Waters reveals that Les ran through a theater preview with sautéed garlic so it would have smell, which we know he also did with Always with Pleasure. Waters likes to do the same with her restaurant.

Remembering Les – This is a conversation with Alice Waters and Tom Luddy, who reflected on their decades long friendship with Blank. Luddy saw his brilliance in filmmaking with the first few films, while Waters saw how special he was at showing the cooking of food. Waters does most of the talking here and shares some interesting anecdotes, like one time where Les took her out onto the bayou on a boat and randomly jumped in the water.

SPROUT WINGS AND FLY, LES BLANK, 1983

The Blue Ridge area is special to me, as I’ve spent many a day up in those gorgeous and tranquil hills, escaping from the hustle and bustle from city life, if only for a moment. For that reason, I thought that my impression of Blank’s foray to the Carolinas would be colored by my bias, but the opposite turned out to be the case.

Tommy Jarrell is as country as they come. He was born in 1901 on the Carolina slope of the Blue Ridge. He lives near the small town of Toast, NC, which is not far from the larger (but still not very big) city of Mount Airy, NC. He is a fiddler, but not just any other fiddley. The old man can play with a vigor of a man 30-40 years younger, and his talents are continually on display in this documentary. He begins with the title song “Sprout Wings and Fly” and the film ends with him playing with impassioned fury at a southern musical festival.

Tommy is a character, as is to be expected from a Blank documentary. He is as southern as they come, with an accent so thick that at times his words are unintelligible. Subtitles are a must. He tells various stories, some jubilant and fun, others bleak and about loss, whether friends, relatives, or others. Some of the stories do not make as much sense as others, but listening to them being told is half the enjoyment.

Drinking is prominent in this feature. As one person says, they had good mountain water, so they made good whiskey, and that helped them make good music. They make their own whiskey and drink their fair share of it, although Tommy never does appear inebriated, although I expect he was much of the time.

Like most of the Les Blank films that preceded “Wings,” there is food, albeit not as much. Their meal consists of meat, chicken, potatoes, cornbread, basically standard southern fare.

While the subject is just as compelling as most in Blank’s films, I was left slightly disappointed. Perhaps it is because he showed so much ordinary scenery in the Louisiana and Texas films and made it look extraordinary. Conversely, the Blue Ridge scenery, which I know is stunning from my own adventures, is limited in appearance. He shows his share of flower, vegetation, and water streams, but there are not many mountain shots. Toast is in a valley, which may be why, but I feel that they should have captured the surrounding, majestic landscape that the people lived under.

The ending credits are a lot of fun. Someone asks Tommy “who is making the film?” and he points to Les, who he says is from California. He then points to Alice who he says “is at the head of this thing.” He is then asked if they got a grant. Yes, he responds, but he doesn’t ask where the government money comes from. As he is talking about it, they show the list of donors that made the picture possible.

Film Rating: 6.5

Supplements:

My Own Fiddle: My Visit With Tommy Jarrell, 1994 – This is a short documentary that was filmed at the same time as Sprout. It gives more background information on Tommy’s life, including many older pictures. He talks about his upbringing and his large family. Most is shot in the same style as the main feature, with music, flowers, and other nature shots. One of the better shots was one that shows a bee pollinating a flower. It ends with someone in a museum giving him a Stradivarius violin and asking him to play it. He manages a good tune, but says that it is not worth the price. Meanwhile, Blank juxtaposes European images from the museum with this distinctly southern music. Film Rating: 7.5/10

Julie: Old Time Tales of the Blue Ridge, 1991 – This is another short, companion feature, although the subject is Tommy’s sister Julie. Her brother’s music is the background as she talks about her life. She was born in 1902, married in 1921, and had 10 children. She sings acapella, mostly ballads and love songs. She talks about her life working in the tobacco factory, and much of the documentary is about her singing. She has a good voice for her age, and she is an interesting subject, but her story does not pack the same punch as Tommy’s. Film Rating: 5/10

An Elemental Approach – Cece Conway and Alice Jarrard were co-directors of this film. They loved Tommy Jarrell and the project was their idea. They raised money and convinced Blank to do it, but reluctantly. He took longer to edit the film. This seems apparent to me having seen it. While it is a good documentary, it does not have the characteristic Les Blank Passion. The ladies say they intentionally started the story with subjects of death, then water, and finally earth. They say that Tommy drank a lot and didn’t eat well, but worked hard, and that is why they thought he was so healthy at that age.

IN HEAVEN THERE IS NO BEER, LES BLANK, 1984

I mentioned above how Les Blank had successfully transplanted his Louisiana and Texas formula to other unique subjects. His documentary about polka is the finest example thus far, and rivals the best of his Louisiana documentaries. Unlike with garlic, which is more of a fringe counterculture, he finds a burgeoning, popular polka in northeastern Polish-Americans. Like with the Mardi Gras participants, the polka fans also drink, dance, and enjoy themselves. The film starts with the title song, “In Heaven There is No Beer,“ which follows with the lyrics “That’s why we drink it here. And when we’re all gone from here, our friends will be drinking all the beer.” Yes, they drink a lot of beer.

Why polka? Everyone interviewed for the film gave nearly the same response. They did it to unwind, to relax, and escape from the grind of their daily lives. Many were blue-collar, but there were also white-collar professionals, including doctors. On the polka dance floor they would truly let go. Some would go further than others. One shot shows an elderly man dancing alone on a beach in his underwear, while there is another couple that does an acrobatic dance where they kick their legs out in unison.

The film covers all facets of polka culture, including the various artists that had a following like Frank Yancovik (not related to Weird Al) and Little Wally, both of whom were polka recording artists. They cover multiple locations, including Buffalo, Connecticut, Milwaukee, and other places that have prominent Polish populations. Even if things vary somewhat from city to city, the vibe is the same. They loved the upbeat music, loved to dance, and loved to drink. Even if the drinking was minimized in the film’s message, there were lots of shots of people lining up at beer stands. Even if it was not on screen, and many times it was, beer was omnipresent in the film.

Much of the film focused on Polkabration, an annual festival on Ocean Beach in CT. Dick Pillar, a polka musician, started it at first as a weekend of performing and dancing. It grew up to a week, and then they started adding days because people would come early. They settled at 11 days, which was the longest that the band could feasibly play. People would come from all over the country to enjoy in the festivities, and it still exists today. A good portion of the polka dancing shots came from the beach festival.

In addition to just showing people enjoying themselves, they give the background and origins. Polka is an international genre. It is not necessarily German, Czech, Polish, French, but it is from all of these areas, and all have their own different versions of polkas. The Polish version has become popularized in America, and subsequently has achieved a large following overseas. European polka had been fading, mostly due to the political turmoil of the 20th century. The Polish had been occupied for 120 years and their culture subdued, but when away from the political constraints and expression is allowed, they were and are prideful and jubilant. Polka is one of the major expressions of this culture (and the easiest to highlight on film), but is one of many. Of course there is food like sausage or “keeshka”, Polish chicken, and other dishes that Les Blank is happy to give plenty of attention.

Like with Always with Pleasure, Les Blank truly captures and a distinct and small, but passionately and enthusiastically celebrated culture. Even though I am not a polka fan, as I am not a zydeco fan, through Blank’s representation, I found myself toe-tapping and understanding why people dedicate themselves so zealously.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements:

Polka Happiness – This is a 2014 interview with Chris Simon who worked with Blank. The idea for the film came entirely from Les, which I think shows compared with Sprout Wings and Fly. Simon took a class on polka and her instructor appeared in the movie, alongside many other interesting people that they would pull out of the crowd. One example was the older dancer, and to the opposite extreme was a young girl who wanted to carry a boom box blasting polka image. Now there’s an image for you.

Criterion: L’Avventura, Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960

My first viewing of L’Avventura was eons ago. It was my first Antonioni, and possibly my first Italian classic film. It is often cited as one of the greatest films ever made, a major turning point in Italian art-cinema, and by extension, world cinema. I remember that my first impression was not altogether rosy. It wasn’t that I disliked the movie, just that I did not understand why it belonged on such a pedestal. In the years since, I’ve revisited on several occasions and it has had a different affect on me. Many foreign art films tend to be more meaningful on multiple viewings, especially those that are selected as part of the Criterion Collection, but L’Avventura is even more impactful because of how it deconstructs the classic narrative plot structure.

I doubt that anyone reading this review has not seen the movie, so please be warned that I am going to spoil major plot points including the ending. It would be impossible to discuss this film openly without talking about the mystery of Anna, so please be warned not to continue reading if you would like to avoid spoilers.

Anna shows early on that she is an apathetic lover. She is not enamored with her lover, Sandro, yet reluctantly and impulsively makes love to him when they first meet. They go away on vacation, and her body language and actions are that of discomfort. When their group reaches a remote island off the coast of Sicily, she goes missing. We do not know whether she deliberately leaves, kills herself, hides, or what happens to her (although there are a couple of hints that are revealed on multiple viewings). This is unusual because her going missing and the initial search on the island occupies an entire third of the film. For the time, it was revolutionary for the narrative to leave the focal plot point so quickly and never revisit it.

That is why it is essential repeat viewing, because you have to understand that Anna is never found to get a proper reading of the film. That is why I was underwhelmed on that first viewing because I kept waiting for them to resolve the Anna situation, and it felt unsatisfying when they didn’t.

Like most of Antonioni’s best work, L’Avventura is a quiet, visual and challenging film. He makes the most of his landscapes, long shots, and juxtapositions of natural scenery versus humanity and technology. The images are startling in their beauty, and that includes the actors, most notably Monica Vitti, whose expressions he uses to tell the story as much as the dialog. The location shots are fantastic, from the abandoned village near Nota to the final shot with Mount Aetna in the background. Antonioni has been described as a painter, and just about every shot can be paused and enjoyed for its visual splendor. That is even more apparent with this 4k Criterion restoration. Antonioni likes to let the image linger and wash over the viewer, which is all the more pleasing with this home video release as it likely was on 35mm back in the 1960s.

Claudia (Monica Vitti) and Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) may be earnestly seeking out and following clues to find Anna’s whereabouts, but as time goes on, they seem less interested in discovering the missing friend and lover. It becomes more about them and their growing relationship. Towards the end, Claudia reveals that she no longer really wants to find Anna, that her old friend’s return would ruin how the situation has evolved. Compared with the resolute Anna, Claudia is needy and confused. She practically begs Sandro to confess his love for her, which he does non-committedly.

Sandro is a flawed womanizer who is not ready to settle down. If Anna had not gone missing, the relationship would have likely been over in the same time it took Claudia and Sandro to develop theirs. He is lost when it comes to love and relationships, uncomfortable, and always has his eyes out for something more promising. That is evident not just by the fact that he is later caught cheating, but that he pursues Claudia during the search for his missing lover in the first place. He is the more forceful in developing this relationship while Claudia is more reluctant, at least at first. When she commits, he strays and eventually breaks her trust.

Morality is at the heart of the film. Most of the characters are immoral and lust crazed. This includes Claudia and Sandro, but also the supporting characters. Guilia and Corrado are terrific examples of this. They exchange barbs during the island vacation, even after Anna goes missing, showing that their marriage is fractured. Guilia is tempted by a youngster and succumbs to his advances, obstinately telling Claudia to leave and tell Corrado that he can find her there. It is as if she is wishing to be found and have their marriage ended. These two characters represent the future of relationships, painting a bleak picture, and helping Claudia reach a level of understanding. If things worked out between Claudia and Sandro, this could be their future.

This movie is easily compared to La Dolce Vita. Fellini’s film was also a monumental and influential piece of art-house Italian cinema. In addition to being released in the same year it shares other similarities with L’Avventura. Fellini strives to contrast the modern and the old world, and uses the framework laid down by Italian Neorealism as his canvas, only he approaches his subject with a distinctively different style than Antonioni. His lead male is also a flawed and immoral person, only his film is from the male’s perspective whereas Antonioni’s is clearly through the eyes of Claudia. Both men at the end come to terms with their shortcomings albeit to different degrees. Fellini’s Marcello is all too aware of how miserable he has come, and that is why he acts out at a party. Antonioni’s final scene of L’Avventura involves a party, but the crime is quiet infidelity rather than creating a scene. It is not until he sees Claudia’s reaction and her drastic change in character that he comes to terms with his failings. When he is sitting on that park bench, sobbing in shame, Claudia touches his head in a show of part pity and part disdain. She has grown up, seen the world, and most likely has become jaded like her forgotten friend, Anna.

Film Rating: 9.5/10

Supplements:

Commentary with Gene Youngblood – This was recorded in 1989 and I had already heard it on a prior listening. Rather than listen to the entire thing, I listened during key moments, including the first third of the film, the Noti sequence, and of course the ending.

Antonioni uses his characters to form an ‘escapist sensuality’ which explains why Anna makes love to Sandro at the beginning, why Guilia accepts the advances of her young admirer, and why Sandro takes up with the young lady near the end (who was likely a prostitute).

When Claudia and Anna change clothes in the yacht, they change the place of each other. Soon, Anna will disappear and Claudia will begin the process of searching for her, taking up with Sandro and becoming Anna.

Not every scene advances the plot, which is why people initially had trouble with the film, while others appreciate this. In the scenes where nothing seems to happen, like when they are taking refuge from bad weather on the island, it contextualizes their situations.

Youngblood talks about the evolution of neorealism. Rossellini was an early pioneer of the genre, but he pushed it more towards being image-oriented in his trilogy with Ingrid Bergman. A good example is with his Journey to Italy, and you can see in that film where the transition from filmmakers like Visconti, De Sica and Rossellini transformed towards Fellini and Antonioni.

Antonioni portrays strong female characters unlike all Italian filmmakers (although I would disagree because of Rossellini’s Bergman trilogy), but still are men’s films. He concentrated on the female component, especially L’Eclisse and Red Desert, but they tend to realize they are living in a man’s world, which in essence, they were. In L’Avventura, the real adventure is Claudia’s journey towards self-knowledge.

Antonioni: Documents and Testimonials – 1966 documentary was the first to get Antonioni’s approval. He is a reserved individual and it is difficult to capture filmmaking by following the process, which is rife with problems and errors.

Grew up in Ferrara, had a bourgeois upbringing, and started his career working at writing and directing plays. He switched to documentary films and eventually features.

Lots of people talk about his early work, including Fellini who collaborated with him on The White Sheik, and had very good things to say.

L’Avventura took 7 months and bankrupted a production company (5 months filming). There were major production problems, including having the cast and crew stuck on an island for a view days. Vitti talks about her experience at Cannes. It was her first film festival, which was a different universe for her. The Cannes audience laughed at the film, hated it, and she felt terrible. By the next day, prominent people came out and stated it was the best film they’d seen at a festival.

Jack Nicholson – essays – Nicholson narrates essays from Antonioni.

1. L’Avventura: A Moral Adventure: People who try to discover his motivation spoil the film for themselves. He does not feel that director’s can or should explain film, and sometimes film cannot be understood. Despite his reservations for sharing motivations about L’Avventura, he agrees because he is sufficiently removed from the project.

Morality is the key, which has changed in human history history. He explores how we go astray and away from our outdated moral conventions, and he is merely portraying our weaknesses.

2. Reflections on the Film Actor: Intelligent actors that try to understand their role can become an obstruction. They should arrive in a state of virginity. Rather than try to guide thing, they should exploit their innate intelligence to employ what the director has instructed. When that happens, the actor has the quality of a director.

3. Working with Antonioni: Jack recounts his experiences working with the master, and agrees with Michelangelo to some degree, but it is impossible to not be thinking during his films. Jack remembers Antonioni saying contradictory things than what he writes in essays. There was very little conflict on the set of The Passenger, and Antonioni even cooked for them in the evenings. Jack tells an interesting anecdote about how the cast and crew returned from lunch and accidentally forgot the director, leaving him stranded, Antonioni pulled him aside and said “Jack, I have to pretend I am furious.”

Olivier Assayas – a 2004 analysis of the film. He breaks it down in three parts.

1. The Empty Center – Can consider it a documentary on the loss of meaning. Anna diving off the boat is A pivotal moment, but not THE pivotal moment. It breaks from the conventional plot because there is nothing for us to hold onto. Anna, and by extension modernity, is the “empty center.” The narrative after the first act shifts from Anna to other characters who pretend to care about looking for her. Do we care?

2. Point Zero – Claudia ends up replacing Anna. The path that Claudia and Sandro follows is unbelievable because they end up in the middle of nowhere. Are they really looking for Anna? The church in Noto is empty and unused and can be equated with the loss of faith.

3. The Resolution – Portrays the solitude of a brand new couple. Meaning disappears. Once they are together, they begin to drift apart towards solitude. After Sandro is caught cheating and Claudia’s flight, there is an acceptance of each other.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

Les Blank, Always for Pleasure. Part Two.

This next trio of Les Blank documentaries fit together well. They are all about Cajun culture, with the first two about the rural and backwoods Creole population, with the boxset’s namesake documentary, Always for Pleasure, a narrative of the types of celebration that can only take place in New Orleans.

DRY WOOD, LES BLANK, 1973

Dry Wood features the Zydeco music of Clifton Chenier, although he is directly profiled in the sister film, Hot Pepper. Like with the prior documentaries, this is a meditative illustration of a mostly ignored yet fascinating culture.

Set in Mamou, Louisiana, Mardi Gras 1972, Dry Wood begins with a group of people in various, outlandish costumes, singing along to Zydeco music in Creole language. It is fitting for this trio of films, as they begin and end with celebration, albeit the latter is on a far grander scale.

In this picture, Les Blank does what he does best. He captures the character moments. The day after Mardi Gras, he shows the Catholic ceremony of people getting ash placed on their heads for Ash Wednesday. From there he shows people living their lives, whether that is a man digging ditches, catching frogs, or kids playing their own version of baseball with a cylindrically squared stick as a bat (not too dissimilar to the type of play that Mance Lipscomb reminisced about in A Well Spent Life.)

Like with many Blank films, there is not too much dialog, and there does not need to be. The first person that speaks directly to the camera and seems aware of being photographed is a gentleman talking about making his first violin, and how he used various natural items that could be found anywhere, either in the house or outside, and it worked. This was 15 minutes into the film, and Blank only features someone when they have something to say.

The latter portion is about food and entertainment, another reoccurring Blank theme. My favorite scene is an outdoor gathering at night, where a number of locals talk about the type of meat they prefer to eat, and what sort they absolutely will not eat. Their opinions are mixed on deer, armadillo and possum, but they ate whatever was being served on that evening heartily. They drank too, and that’s when the fun begins. As the night progresses, the men start dancing and then play fighting, falling down all alongside each other. These are grown men, but this is the type of roughhouse play behavior expected of most kids. It is the booze that binds them together, and they are absolutely plastered on this night, as they likely are on many nights. It speaks to Blank’s talents as a filmmaker that he was able to capture them so relaxed and in their element.

Some of Dry Wood is not for the faint of heart. The day after the men have their fun, they kill and butcher a hog, while the women prepare it. At one point they saw the snout off of the hog, and later it goes into a meat grinder to later become headcheese. A baffled youngster wonders, “is this what is in headcheese?” He doesn’t like the response, and won’t admit whether he liked it or not.

Film Rating: 8

Supplements:

A Cultural Celebration – Taylor Hackford gives another interview and talks about how culture is cuisine. It is first infused into food, and then into music. His piece is about both sister films, with Dry Wood being about the cuisine and Hot Pepper about the subsequent music. Hackford talks about how Blank was looking for the so called “golden moments” where people are captured with their guard down. One such example is the scene where the grown men are dancing around drunk, and there are many others

HOT PEPPER, LES BLANK, 1973

Blank goes back to the well with this follow-up documentary, which is a profile of Zydeco accordion musician and “King” Clifton Chenier. It begins with him playing a concert in Lafayette, Louisiana, and this is the music that scores the film. They cut back and forth between the concert and Louisiana life, like they do in Dry Wood. The great scenes are again when people are unaware or apathetic about the camera, and do their own thing. One cute scene has a girl playing by hanging around a street sign. There are other people that just walk by, minding their own business, some working on the railroad, some going about their day.

The best scenes are the landscapes captured with the Chenier music in the background. There is one sequence that shows a beautiful country sunset, followed by a dark night with the only visible object a pair of dim headlights. This is what Blank excels at, making the mundane appear magical.

Much of Chenier’s music is upbeat, but the most beautiful song, “Coming Home,” is peaceful and serene. It is a scene that Clifton wrote for his mother before she died, yet she unfortunately never was able to hear it. You can hear the emotion in his voice as the accordion slowly and poetically follows along. Blank focuses on landscape scenes for much of this somber scene and it becomes a meditation. We see sky scenes, birds flying, and a number of engrossing landscapes. It is easy to get carried away into this world.

While Hot Pepper has its moments, it is uneven and occasionally jarring, For example, it has a lady speaking frankly and randomly above her vagina parts. The major failing is with Chenier, who is not as captivating a subject as Lipscomb or Hopkins. The only time we see him away from the stage is when he is playing on the doorstep of a house, sitting with some friends, but he does not reveal much about himself or his world view. He just plays.

ALWAYS FOR PLEASURE, LES BLANK, 1978

As one subject says midway through this celebratory documentary, New Orleans is the “city that care forgot.” By that he means that is the last place in America where someone can truly be themselves be free. They are free to dance around in public, drink, sing, shake their body, chant, or do whatever they desire.

The film begins with a slow funeral march through the street. As Allen Toussaint puts it, the march to the funeral is slow and that’s when the mourning takes place. The way back is when people cut up. Life goes on, and people enjoy themselves. The band members are the main line, and they perform the somber music on the way up, and the upbeat, party music on the way back. The second line are the dancers and singers, who give their old friend a send off with spirit and revelry.

The majority of this documentary shows people partying in various ways. There are people drinking up a storm on St. Patrick’s Day, with overhead shots showing a sea of green. People laugh and sing along Bourbon Street, hooting and hollering, meandering through the street moving to the rhythm of the music.

A Les Blank documentary would not be complete without food, so he takes a break from the partying to show the staple meals of New Orleans, red beans and rice being made. One expert talks about the proper way to eat a crawfish. You shouldn’t break open the shell, but just bite off the head and squeeze the meat into your mouth.

The title cards share a bit of history. Many of these traditions originated with slaves. Initially the owners would let them have Sundays off of work to celebrate. Eventually that permission was curbed, but slaves would find ways to get outside and enjoy themselves. Mardi Gras was a free-for-all, and that was when all slaves were allowed to celebrate. Thus begun the tradition that continues today of yearlong merriment with the party of the year every May.

Always With Pleasure ends on a high point, with the wild, rousing traditions of Mardi Gras. People march in the street. He shows people with percussion instruments, singing and dancing. Some people are dressed up for the occasion, while others are dressed in regular clothes, having fun just being there and singing along. “Ooh-na-nay!” they chant as part of a call-and-response mantra as they march along.

The main attractions are the Big Chiefs, some in pink feathers, some in white, some in blue. They even show a young kid wearing an elaborate costume in white, probably having more fun than he’d ever have in his life. These are the Indians and they are serious about their Mardi Gras presentations. They make their own costumes anew every year, and destroy them afterward. They are also always trying to outdo the other tribes. In doing so, they entertain themselves and everyone around them. New Orleans, at least some of the time, is where “care truly forgot.”

Film Rating 9/10

Supplements:

Lagniappe – This is a short film of 25-minutes with additional footage that was cut out of Always for Pleasure. It begins with a street band marching through Bourbon Street to a predominately white crowd, which is contrasted with much of the main feature that showcased African-Americans. We see more of musicians, like Professor Longhair, who also appeared in the main feature, who plays the shit out of some piano. A singer and guitarist do a duet together, with racy lyrics like, “if you want to feel my thigh, you gotta go up high.” Finally, there are more shots of the Indians singing. There are never enough shots of the Indians.

Celebrating a City – Interview with Maureen Gosling, who did just about everything else on this project. During the shooting, they stayed with Michael P. Smith, who was a famous New Orleans photographer. He gave Blank a lot of ideas on where to shoot. Blank was more interested in the celebrations off the beaten path, which is probably why much of the Bourbon Street parties were cut out of the main film in favor of more time with the Indians. New Orleans has parades everywhere, and they only captured a small portion of them. On the day of Mardi Gras, they spent an exhausting 10-12 hours walking down the street with heavy equipment, getting as much coverage as possible, and practically collapsed afterward.

My favorite story was how they cooked red beans and rice for people involved with the film. They even did this for special screenings. They would cook the meal and fan the scent towards the filmgoers as they watched. Their reward was they got to eat it afterwards. Now that would be the ultimate way to experience New Orleans without actually being there.

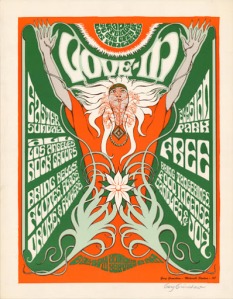

Criterion: Jimi Plays Monterey, D.A. Pennebaker, 1986

Jimi Hendrix was like a being from another planet. He showed up, transformed culture and music as we know it, and then he quickly said goodbye, leaving us to marvel at him nearly half a century later. His performance at Monterey was still relatively early in his three album career, but it was a monumental moment. He had already been immensely popular, but this was when he truly arrived, and he frankly blew people away.

The documentary is introduced with high-speed graffiti artist painting a picture of Jimi in his element while “Can You See Me?” plays in the background. He begins with a beige base as the first layer, where we can barely make out the primary features of Jimi’s face. From there he applies other paints and more layers. When he gets to the red, he sprays it seemingly randomly, but it becomes Jimi’s trademark bandana. When he is finished with his creation, the song is over and the poster boy for late 60s guitar psychedelia is clearly fashioned on the wall.

The exposition is brief, which is fine. The core element of this documentary is the performance. John Phillips narrates the origins of Jimi’s career, including beginning playing in clubs with R&B acts, being discovered and eventually managed by The Animals, who brought him to London and changed many different worlds, including Jimi’s. As Phillips puts it, Jimi “went like a fireball once he hit London.” The Experience was formed and the rest is history.

The obligatory setlist:

Saville Theater, 1967

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Wild Thing

Monterey Pop Festival, 1967

Killing Floor

Foxy Lady

Like a Rolling Stone

Rock Me Baby

Hey Joe

The Wind Cries Mary

Wild Thing

People did not know what to make of him. There are alternating shots of Jimi shredding, nonchalantly playing complicated riffs on his guitar, while making unnatural sounds on his Stratocaster. There are occasional shots of the crowd. Many are simply floored. They had never seen anything like this. Others are exuberant, moving to the music.

Even when he talked, he sounded like he was from another world. “Dig, man .. “ as he liked to say, “laying around and picked up these two cats” as he points toward Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, his Experience bandmates.

He played covers, old blues standards, and a handful of his own hit songs. This was before he had much of a body of work, like my favorite Axis: Bold as Love, which he would record next, and Electric Ladyland in 1968. One great thing about Hendrix is that his own material was not required. Covers would be staples in his live shows until the very end, because he somehow transformed them into Jimi Hendrix songs.

He was ever the showman and pulled out all the stops during his Monterey performance. During “Hey Joe”, he plays a solo while picking with his teeth, and it sounds no different than the brilliant solos he played with his hands. Later he plays another solo with the guitar behind his head, and again, it sounds perfectly fine. He effortlessly swivels and moves his guitar around, yet never misses a beat. He actually makes such complicated playing seem easy as he is completely relaxed while playing (probably thanks to chemicals).

It is the final song where things finally go bonkers. Before he covers The Troggs’ “Wild Thing” he combines the American and English national anthems into something unrecognizable and otherworldly. He uses the tremolo and feedback to create sounds. At times they sound like the driving of a car; at others they sound like a space ship.

“Wild Thing” is a relatively simple song. Even I can play the primary riff and it would be flattering to say that I’m even a beginner. Jimi takes the simple and makes it complex, and frankly just destroys the song. Between the verses, he continues to use his weapon to make sonic and beautiful sounds. Towards the end of the song, he destroys his guitar, with it still plugged in. Even in destruction, it manages to sound like he is “playing.” Finally, it burns in flames, still transmitting sound.

Backstage before the show, he and Pete Townsend had a debate as to who would go on first. It apparently became contentious and they had to flip a coin. When it was settled, The Who would go on first, but that just inspired Jimi to push his performance to another level. That he did. As his guitar was burning on stage with the crowd going out of their collective minds, I’m sure he was thinking, “Pete, take that.”

Film Rating: 9.5/10

Supplements

Commentary with Charles Shaar Murray –

He calls Jimi’s performance one of the epochal single performances in 60s rock and roll. Jimi was great because he had roots in real rhythm and blues, whereas the Englishman just had the records. Nobody had done the type of things that Jimi did with guitars. Stratocasters were not designed with this type of playing in mind. Nobody envisioned this.

What was amazing is that this performance and the heights he reached in his career were a mere year before he had left the USA for London. He was an avid drug user, and was on acid for this performance, and that inevitably helped with his creativity and innovation with sounds and feedback.

It is interesting that he played Bob Dylan songs. Dylan was an influence in many ways. Not only did he write some of the best songs of the era, but he had no voice and still managed to sing with success. Jimi was self-conscious about his own voice, which was hardly the strong choir-like voice of R&B, and probably would not have tried singing his own material if it were not for Dylan. He paid tribute by playing the folk hero’s songs, yet like all other covers, he played them in the Jimi way. He played “Like a Rolling Stone” with the same chords that he played “Wild Thing,” and Dylan’s lead guitarist was in the audience and bore witness to how the song transformed in Hendrix’s capable hands.

His genius is that he plays so casually. On “Rock Me Baby,” he was playing keyboard, horn and guitar riffs all on his guitar, while singing. If you looked at his playing, you would barely notice. He made the complicated seem mundane. His guitar would get out of tune from his playing, but he was able to gradually bend the strings back into tune while playing. Nobody else could do that.

Additional Audio Excerpts – There is plenty of biographical information, including details about his rise to success and arriving at Monterey. This is an audio recording of 45 minutes.

Interview with Pete Townsend – “Jimi was out of his brain, on acid, and wouldn’t discuss the question” of who went on first. They were both going to introduce pyrotechnics for the first time, so part of the argument was who would do it first. Townsend’s perspective was that he didn’t feel like following Jimi because Jimi was far more talented. Jimi’s team did not see it that way, as it was more of him wanting to be the first to do something special.

Criterion: The Night Porter, Liliana Cavani, 1974

I knew going in that The Night Porter was controversial. What I didn’t expect was for it to be so perplexing, confusing and illogical. It is certainly artistic, brave and creative filmmaking, but it is also needlessly provocative, tasteless, and in some ways insulting. I’m not referring to the nude or sexual scenes, most of which are tame given the Italian cinematic landscape of the time (see any early 1970s Pasolini film for an example). What is unsettling is the way two people deal with their tragic memories of captor and prisoner.

From a filmmaking perspective, Cavani is right there with her art house Italian peers from the era. The film looks tremendous, especially in this restored Blu-Ray version. She uses crooked angles for many of her shots, which adds to the disturbing nature of the narrative as it unfolds. She shoots in a darker hue, with lots of muted blues, greys and blacks, which looks great, yet is consistent with the mood of the primary characters.

Most of the early film consists of a back-and-forth between the war years and a Vienna hotel, where one of the Nazi camp leaders, Max, works as a night porter. He encounters one of his prisoners, Lucia, who recognizes him and that triggers some terrible memories.

The flashbacks are of the harsh realities of the war. There is one scene where Germans are taking shots at kids on a swing set, disturbing because it combines a playful, jovial activity with atrocity and murder. There is another scene where a large group of prisoners are stripped naked in a room and examined by the Nazis. This is not an erotic scene, but instead one of abject humiliation, not just of Lucia, but all of her imprisoned companions.

The best and most effective scene comes about a third into the film, and is a strong example of contrasting horror with beauty. Both Max and Lucia are attending a performance of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. They see each other in the audience, and again the memories are triggered. The wonderful, uplifting music continues in the background as we see a woman’s dormitory, crowded with cots a few feet away from each other. Lucia is lying in one cot as a German soldier is raping another woman within earshot. There are other powerful flashbacks, such as an instance where her captor inserts two fingers into her mouth, simulating fellatio. She looks fearful and apprehensive as this happens, still with the joyful music playing in the background. When we see her in the audience of the performance, her face is solemn and she looks distracted. This is not a pleasant memory to re-live.

From there the plot takes a left turn into the perplexing territory that I noted above. There are a group of former Nazis that Max belongs to. Most of them are proud of their deeds, yet Max feels shame. They know of the “witness” to their crimes and agree that she needs to be eradicated. The audience would expect Max to act according to the orders of his peers, but he defies them. Soon enough we will discover why.

This is where I have problems with the film. Max and Lucia are in love. He calls her “my little girl,” confesses his love, and they rekindle their romantic and sexual relationship in the hotel. Lucia reciprocates the love, yet there are still grossly disturbing flashbacks, like her singing a song bare-breasted for the German soldiers, and receiving a severed human head as her reward. This is what is baffling. The Stockholm Syndrome is a real thing and may have happened to a certain extent during the war, but being a captor of the Nazis is not the same as Patty Hearst being captured by the SLA.

Together they rebel against the Nazi conspirators that want to silence Lucia. He wants to save her, while she does not want to expose him. They want to live together even if circumstances, society, and their wartime past makes that an impossibility. They become the prisoners, and the post-war society is their captors.

Even though this turn defies logic, I am willing to forgive it to a certain degree because Cavani is using the horrors of war and imprisonment to make an artistic point about post-war society. She goes out of her way to reveal Max’s shame for his actions, and how he is protecting his “little girl” as a sort of penance, while Lucia is masochistically re-living a version of the worst years of her life in order to support him. They suffer in the hotel room because of their isolation and inability to escape. They starve, just like the prisoners during the war were starved. This could be read as society being imprisoned in 1958 by not being able to come to terms with the terror, with some who participated in the torture quietly being prideful of their actions, and the sufferers still haunted and unable to deal with the transformed world.

In this last paragraph I am going to spoil the ending, so please stop reading here if you have not seen the film.

Lucia had no option to leave her captivity during the war. The Germans, including Max, would not allow it. In 1958, he even chains her to the room, which is unnecessary since she is committed to remaining with him. Together, they have limited options. If she goes to the authorities, Max will be discovered and punished. Max has no options that do not involve killing Lucia, since she is the witness. Their only avenue is to leave willingly, famished, with barely enough energy to move one leg in front of the other. Their ending is inevitable and tragic, as they are shot in cold blood as they try to cross the bridge. We can tell from their body language that they have accepted this ending as inevitable. In some respects, this is also Cavani attempting a form of closure. The captor and the prisoner are gone, however tragic, but life goes on. The world needs to accept what was terrible and move on.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements

Introduction to Women of the Resistance – Cavani introduces the film and says that The Night Porter originated with this documentary project for TV. She had watched a lot of western footage between 1940-1945, but could not get any footage from the Eastern Block. She says it is the only resistance documentary that focuses on women.

Women of the Resistance, 1965

Much of the documentary consists of archival footage and interviews with women who were directly involved. The images are not sharp, but that probably has more to do with the TV format rather than any restoration issues.

As with anything about the war, this is difficult and not altogether pleasant to watch, but it is rewarding. There are difficult issues that the women discuss, and one simply refused to discuss her own situation because it was too difficult.

The film begins with letters that imprisoned women write to their family hours before they are to die. All of the letters are powerful. One example: “Don’t think of me as being any different from any soldier on the battlefield.”

The resistance began in France and united all against the anti-fascist parties. Many were killed in the resistance, men and women. The women that participated were sometimes in service roles, but they also served as effective partisan fighters. Just like with the men, they suffered harsh treatment and persecution if they did not go along with the fascist regimes. Of the female resisters, 623 were shot while 3,000 were deported to Germany. The captured women were beaten, had their hair pulled out, starved, and suffered countless other tortures. One lady tried to make earplugs out of her clothing in order to not hear the screaming. They did not work so she tried to kill herself.

There are many topics in the documentary that would form the narrative of The Night Porter. While many of the subjects did not describe the sexual torture on camera, Cavani likely heard many such stories and chose not to broadcast them. Starvation of course becomes a theme, as Lucia and Max are unable to obtain food, not even from their neighbors, yet they live in a free society and have money. In the documentary, the ladies talk about how they were starved and many would die from hunger. One way they were tortured was by being tantalized by delicious food that they would not be allowed to eat. This comes into play in The Night Porter with the jam that Lucia eats ravenously. She sees it on the counter and cannot contain herself. The only difference is that in this captivity, she is allowed to eat what is in the room, but nothing else.

Most of the stories are tragic and painful, but there is an undercurrent of gratitude towards women who served and satisfaction from the participants. After the war, these women are remembered for their service and bravery. One person states that the women were sometimes sent in with the front lines because they simply had more courage than the men. All women that survived are proud of their experience and their service, even if the memories are filled with sorrow. Most importantly there is still a sense of duty to be watchful and wary of the potential of fascism and racism to come back. We know from history that it does not happen again, at least not anywhere close to the extent that it happened in the war.

Film Rating: 7.5/10

Liliana Cavani 2014 interview – She knew right away that she wanted Rampling or Mia Farrow to star in the lead role. She made the right choice as Rampling was brilliant. She did not want the female character to be Jewish because she did not want it to be about race or the Holocaust. Instead, Lucia was the “daughter of a socialist.” She had to make the movie as a tragedy because of the era. It was not possible to make a happy film about this topic.

She speaks about the controversy surrounding the film. Catholics came out against the film, although they were not bothered by the torture or misogyny. They were simply against the sex.

Criterion Rating: 7.5/10

Criterion: Tootsie, Sidney Pollack, 1982

At one time in my life, I spent a year living in North Hollywood. It was almost like living on a different planet. Even though the northern side of Laurel Canyon and Mulholland Drive is more suburban sprawl, it is indirectly linked with the film industry. Most of the people I worked with had some aspiration of working in Hollywood. Many had written scripts; others had dabbled into acting, while others were more interested in the technical side of things. When we went to lunch, the waiters and waitresses were gorgeous. We didn’t have to guess which ones arrived with the hope of becoming stars.

Most of the people I met didn’t make it in the business. Most won’t. It is a cutthroat industry and there simply aren’t enough jobs out there for the people who want for them. If people had dedicated their lives and failed, I could see them doing something absurd or even unscrupulous as a result of such desperation.

That sort of desperation is where Tootsie comes in. It takes place in New York, which makes it even more complicated. There is a film industry, but there is also Broadway and television work, and ultimately fewer high paying jobs for a full-time actor. In the case of Michael Dorsey, he was brought up as a New York “actor’s actor.” He had undeniable credibility and some ambition, but was suffering because of his inability to make compromises. When the truth hits him, when he hits the bottom of his career, he arrives at the ultimate compromise and both a comical and absurd way of “selling out.” He becomes a woman.

Even though Tootsie is a mainstream comedy with a ridiculous premise, it touches on a number of realities. The fact that actors face such an uphill battle when it comes to career choice is a minor reality. It is more the reality of gender roles and inequality that drives this movie and is the source of the comedy. It also speaks to the reality of the times. It came out on the heels of the women’s liberation movement. Society had progressed by that time and there was more equality in the workplace, but it was (and to a certain degree still is) a man’s world – and that’s not only in the entertainment industry. Tootsie turns the idea of inequality on its head. It is the man that has to change gender roles in order to further his stagnating career. As a woman, he has a sense of security.

Tootsie could not be made today, at least not in the way it was made in the 1980s. In some ways it would be too tame today, since transsexualism is becoming more commonplace. As I write this, a show about a transsexual-themed show just won a Golden Globe award. We also live in a more politically correct world. The idea of someone being objectified is not as prevalent today thanks to countless sexual harassment lawsuits. It probably does happen, but a boss would have a hard time getting away with calling a female employee Tootsie, pinching her bottom, or placing her in a situation where she has to kiss someone against her will. Things are different today. While Tootsie was an effective comedy in the 80s, it is funny today in a nostalgic and dated sense. It is like we are watching an older world being poked and prodded.

In some ways, Tootsie is an anti-feminist movie. Dorsey is a scoundrel of a man, someone who will use the same line on three women at a party, and will use privileged information under the guise of Dorothy to try to get a woman into the sack. He is morally weak, and the fact that he uses womanhood to jumpstart his career is in itself chauvinistic. He is depriving other capable women from the same opportunity, one of which is a friend of his who he casually sleeps with while he longs for another woman.

The character arc of Dorsey makes him become feminist to a certain degree, at least as much as someone from his beginning mindset could in the early 1980s. He realizes that women have challenges and that not everything is a bed of roses. They are objectified, ridiculed, and they are not expected to retaliate. He gives advice to Julie (Jessica Lange) to stand up to her ill-behaved boyfriend (whose actions aren’t dissimilar from Dorsey’s), yet she fails to stand up for herself. Julie doesn’t have a backbone, yet Sandy (Teri Garr) has just as forceful a personality as Dorsey, but she is lied to, cheated on, and treated with complete disrespect.

As a film, Tootsie is decent. The filmmaking is not particularly inspired and they rely a great deal on montages. The soundtrack, most notably the annoyingly catchy “It Might Be You” song is also dated. It is elevated by a brave gender-bending performance from Dustin Hoffman, some terrific improvising from Bill Murray, and a witty script.

Film Rating: 6.5/10

Supplements:

Commentary: This one took place in 1991 with Sidney Pollock for the original laserdisc. This was in the infancy of audio commentaries and it shows, although we learn some new and interesting things about the production.

The script had believability problems from the beginning. They had to establish that Dorsey had the chops to pull off acting as a woman. They spent the beginning of the movie and the first of many montages as exposition to establish his credibility as an actor.

The first shot of Hoffman as Tootsie was a risk because it is a jump in time. They had some logical problems because they did not show expositional shots of the mental and physical process of his deciding to become a woman. He simply appears in costume. Later they would show a montage with him doing the makeup and transitioning from a man to a woman. I think it was more effective the way Pollock shot it. It is a great, abrupt and funny entrance for Dorothy Michaels.

Interviews:

Dustin Hoffman – He was self-critical. He was fighting with Pollock on the set. One thing he wanted was a more farcical scene in the bedroom with Lange, but there were many other fights. He talks about how people generally get casts as character actors unless they are lucky enough to get famous. The Graduate got some reviews that said Dustin was ugly. He says that what defines a good piece of work is it doesn’t date. He feels The Graduate and Tootsie do not date. I agree with the former, but not the latter.

Phil Rosenthal, Everyone Loves Raymond creator – The “guy in a dress” is oldest gag in world, going back to Ancient Greece, but Tootsie works because he sets up the scenario in a modern world that a man would go to that length. Tootsie is a sitcom, believable people in incredible situations. They chose a soap opera because it is believable that an actor can get that role, can get stuck in that role, and can have a live, televised scenario. He says the movie is not a lesson in feminism, but Dorsey becoming a better man.

Dorothy Michaels and Gene Shalit – This was a silly and unused interview from the movie. It invents a theatrical background for Dorothy, who has mixed feelings about being in a soap but has to make some money. “Do you feel that you are Emily?” “I feel that I am Dorothy Michaels playing that part.” She even asks Shalit out.