Blog Archives

Les Blank: Always For Pleasure. Final Thoughts.

Over the last month or so, I have tackled the terrific Criterion box set, Les Blank: Always for Pleasure. It consists of fourteen main features, countless supplements, and various other short films. It is a treasure of riches, as Blank takes us through Cajun country, up to Northern California, across the country to the Blue Ridge Mountains, up north to New England, back to California, Louisiana, and ending with a spiritual celebration in New York City. In the process we experience various different cultures, foods, music, and vibrant characters that are so far fetched that they cannot be made up. Les Blank’s world is about as far from the mainstream as possible, but it is about living life to the fullest, enjoying the simple things, and respecting traditions.

How can I summarize such a journey? I really cannot, as I’ve already written nearly 10,000 words as I rode along. You can read them here:

As a recap, I’ll look at the different types of topics that Les Blank explored, and how his vision was unique compared to so many others.

Music

Today it seems like most musicians and bands with a fan base have their own documentary. They are relatively easy to put together thanks to DIY independent film avenues and crowdfunding like Kickstarter. The larger the band, the larger the production, and the sales are nearly guaranteed. Most of these documentaries fall into one of two categories: the career narrative and the concert film. While some can be extremely good, such as somewhat recent documentaries on Rush, Metallica and Big Star, but they follow the same formula. They talk about the band’s origins, their success, breakup, and aftermath. They show concert footage and talking head interviews with anyone and everyone they can find. Many of these are inspired by VH1’s Behind the Music more than filmmakers like Les Blank or D.A. Pennebaker, and that’s a shame.

In many ways, Les Blank was a pioneer of the music documentary, and in other ways he was completely isolated from the genre, on his own island. He started with Dizzy Gillespie (which is not on the disc), and from there, he found some blues artists in Texas and Louisiana. He ventured further away from the Deep South, and covered artists that would not be found at the top of a music chart or featured on MTV. He wasn’t interested in only the musician, but also the way that they lived, the place and culture that molded them, and, perhaps most importantly, the affect they had on others. The one common thread among all of his musical documentaries is people could dance to the music. The people who experienced and enjoyed the music were just as essential to the documentary as the musician and the music.

Les Blank’s music work predated MTV, VH1, and Kickstarter, although it eventually caught up and he worked concurrently with the transformation of audio to video. He undoubtedly saw the musical documentaries from Pennebaker, Scorsese, Demme, and others, and you would think those would influence his style. Nope. From the first documentary on the disc, The Blues According to Lightnin’ Hopkins in 1968 to the final documentary, Sworn to the Drum, very little had changed. He had as much interest in how and where Hopkins grew up as he did Francisco Aguabella. He could not travel to Cuba to understand Aguabella, but if it were politically possible, he unquestionably would have. It is no coincidence that both of these documentaries are just about a half an hour long, feature the artist’s music as the soundtrack, show people dancing to the music, and explores the roots and ideologies that make them express themselves through sound.

Food

Again, Les Blank was a pioneer when it came to documentaries about food. Unlike with music documentaries, food via the mass media found a home almost exclusively on television. Blank probably had more influence than he gets credit for, since it was the Cajun cuisine that became a large part of cooking television. One of his subjects, Paul Prudhomme, even had his own short-lived series on Public TV during the nineties. Other personalities like Emeril Lagasse and Justin Wilson also became Cajun celebrity chefs. As Blank demonstrated, Cajun cuisine is delectable, and until the 1990s, was virtually unexplored as a mass consumer cuisine. Today you can get Cajun food everywhere, but not the type of food that Les Blank’s subjects cooked.

Food was such a central subject with his documentaries, that it comes as a surprise that only two of the films on the disc were specifically about cuisine. He explored garlic with Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers and Cajun in Yum, Yum, Yum! A Taste of Cajun and Creole Cooking. Despite it not being the sole subject, food is a large part of most of his documentaries. For musicians, he wants to know what they eat in addition to where they live. When he looks at cultures like Cajun or Polish-American, he spends a lot of time with their foods of choice. Even with Tommy Jarrell in Sprout Wings and Fly, he has a scene at the dinner table where they serve traditional southern food.

Les Blank loved food and it showed. In the supplements, we learned that he would run around movie theaters with aromatic dishes prior to a screening to add another layer of immersion to the experience. Can you imagine watching a movie about New Orleans while smelling red beans and rice? What about Ten Mothers while sniffing the strong scent of garlic? Even though I watched all of these movies without the hint of an aroma, I felt like I could taste and smell all of the food. And it was good …

Life

Even though each documentary had a subject, Les Blank’s films were just about the way people lived. Whether they were laborers in the middle of Texas, hippies in California, or country folk living in the mountains, we got to see what they did, how they behaved, and we heard their thoughts and ideas on life. As I reflect on this boxset, I think back to the early documentaries where he shows gorgeous landscapes, stunning sunsets, or just people wandering to and fro. People fascinated Blank, and that fascination was not restricted to his subject. He was enthralled by people running in a field just as much as he was a crazy actor arguing with a director (from Burden of Dreams about Herzog and Kinski, which was not on the set), or an old musician talking about playing baseball in the fields as a kid.

Food and music were just two examples of the many outlets people found to enjoy life. The Maestro dedicated his life to painting hundreds or perhaps thousands of pieces, not for economic benefit, but for his own passion. Blank loved to show people that were proud of something, whether it was a distinctive physical imperfection like a gap between two front teeth, or people who tried to compete with each other by wearing the best costumes at Mardi Gras. He showed people having a good time however they could. It doesn’t matter whether people were poor and lived in small Texan towns, or if they were doctors and lawyers that wanted to dance polka for a week, there was a smile on their face. If a nagging tooth gets in the way, then just pull it out and enjoy life.

Thanks Les Blank for showing us your world.

Box Set Rating: 9/10

Les Blank, Always For Pleasure. Part Four.

GAP-TOOTHED WOMEN, LES BLANK, 1987

Again, we have a Les Blank topic that comes completely out of left field. Who would dream of filming a movie about something as minute as a slight wedge in between someone’s mouth? Les Blank was that man, and based on what other topics he approached, he must have been unusually attracted to women with the dental distinction.

The big question is whether there is some mystique to gap-teethed women. Are they sexier than girls with a block of bright and shiny whites? That’s probably in the eye of the beholder, just like some people with find various imperfections attractive.

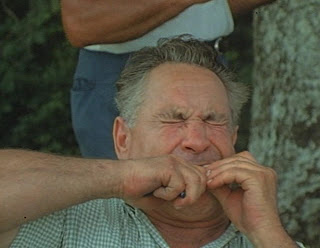

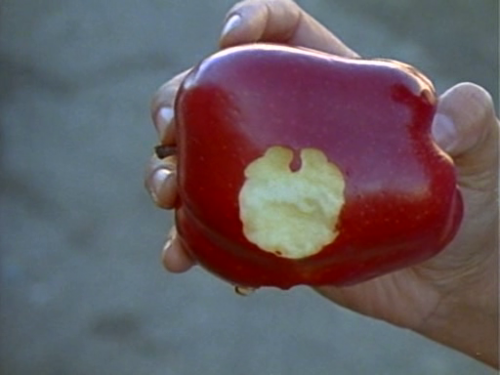

Blank takes the topic further and uses it explore the concept of beauty and self-image. He opens with a girl who bites into an apple with her gap-teeth, and proudly leaves her ‘signature’ in the piece of fruit. Chaucer is referenced aplenty, and sometimes in the manner that he adored gap-toothed women. The Wife of Bath had gapped teeth, and she also had five husbands and countless other lovers. Her affliction did not leave her for wanting. Others have studied the term and traced “gap” back to the word “gat,” which meant lecherous, casting not the most favorable shadow on Mrs. Bath.

Some women are self conscious about their gaps. A lot of dentists consider it a flaw and aggressively will try to convince women to close them (or maybe they just want the business). They are more common in other words, such as Indian, where one lady says “half of India has gap teeth.” That could be due to a lack of dentistry as well as any cultural preference.

To balance out those with image problems, there are plenty of famous individuals that are considered beautiful. Lauren Hutton made a living out of her gap-tooth, and appeared in the movie doing street interviews. Madonna, also gap-toothed, is likely also proud. At last check, she still had the gap, but she did not choose to appear in the movie. Hutton’s message is to accept one’s own imperfections and turn them into your own uniqueness. Others take it further, such as one lady who screams for “Gap Pride!”

Blank gets some points for pursuing a topic that most could not even conceive of, and using it to explore the incomprehensible topic of women’s self-image and male attraction. Well done, Les.

Film Rating: – 8/10

Supplements:

Mind the Gap – This piece shows his office, cluttered with stuff he loves. Includes gap-toothed women, garlic, and red headed women and was going to make a movie about the latter. Susan Kell talks about his fascination of Chaucer, and the wife of Bath.

They had a Casting call advertisement and had the phone ringing non-stop. Who knew there were so many people with gap-teeth and eager to show the word? Te gist was that most women were excited about celebrating what had been seen as a flaw. They unsuccessfully tried to get Madonna. They also tried for Whoopi Goldberg, who was local to Berkeley and not as famous. She probably would have done the film, but her career blew up during the filming and she was no longer available.

YUM, YUM YUM! A TASTE OF CAJUN AND CREOLE COOKING, LES BLANK, 1990

Les Blank has some great titles, and this one fits the subject the best. I would say the vast majority of his documentaries have some element of food, even if it is not the primary topic. He just loves food.

This time he returns to Cajun country to focus exclusively on the cuisine. We meet up again with an older Marc Savoy, who we first met on Spend it All. He throws a bunch of ingredients in a pot that are then cooked over a country wooden fire. It is called “Goo Courtboullion,” which means absolutely nothing to me, but looks like the most delicious thing anyone could taste.

The guys out in the wilderness haven’t heard of Paul Prudhomme, which turns out to be a good time for a transition, and they then show him signing books in New Orleans in the next scene. He is the owner and celebrity chef of K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen. What’s interesting about Prudhomme is that this is ages before the Food Network, Top Chef, The Cooking Channel, and the concept of celebrity chefs. Prudhomme was one of the originals, and he along with others (Justin Wilson, Emeril Lagassee) popularized Cajun cuisine in the kitchen. When one watches this documentary — and perhaps many TV executives had — it is easy to understand why.

They cook a variety of dishes, with a focus on whole foods and nothing manufactured. One lady dismisses garlic powder, saying, “that’s the new stuff they got. No good.” Blank, ever the garlic aficionado, would most definitely agree.

Many more dishes are made, including a variety of Etoufees, each looking more delicious than the last. I seriously challenge anyone to watch this 30-minute documentary and not eat something during or immediately after.

Marc Savoy reappears to presciently comment on Louisiana cooking from outsiders. He ordered Cajun fish at Disneyland. The fish itself was fine, but they covered it in a black pepper that made it inedible. He actually took the fish to go, removed the pepper and ate it. I wonder what he would make of all the Cajun restaurants that have sprouted up all over the country? Would he take their finest dishes, eat a bite and then customize the rest later in his hotel room? My guess is yes.

The best quote is:

“What’s better than a bowl of gumbo?”

“Two bowls.”

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements:

Marc and Les – When recruiting Savoy’s participation, they called him up and said “come on over, making gumbo.” Marc credits Les for meeting his wife Anne, which was sort of a half-truth because he met her at a festival that he wouldn’t had attended if not for Les. Les would remain friends with a lot of his subjects. Savoy was no exception.

THE MAESTRO: KING OF THE COWBOY ARTISTS, LES BLANK, 1994

The overall theme of “Cowboy Artist” Gerry Gaxiola is that he does not paint for money. Like with Anton Newcombe, made famous by Ondi Timoner’s Dig!, he is not for sale. The continual reminder for Gaxiola in the film and the features is that for him, art is a religion and not a business.

What’s odd about Gaxiola is that the grew up in San Luis Obispo. Even though he grew up in a ranch, southern California does not exactly scream cowboy country. He speaks without a southern accent and his values are more common in Berkeley, where we resides, than say, Texas or anywhere else in the deep south. Yet he travels with a Cowboy getup, complete with the hat, boots, and even utility belts that he creates himself to holster his “guns,” which would be paintbrushes. Is he an artist or a gimmick? If you ask him, the answer would indubitably be artist, but Les Blank’s portrayal leaves the question on the fence.

He began having a Maestro Day, which would be a daily celebration where he would invite crowds to see him perform. He would do some artistic endeavors, like a “Quick Draw” where he would paint at warp speed. The rest was more performance, including singing and dancing. He would get the crowd involved, awarding best-dressed cowboy. There would be treats, and it sounds like a fun day for the family. Despite the success of Maestro Day, he quit it after 13 years because he was moving more in the direction of entertainer than artist and that is not how he wanted to be seen.

The man was not without talents. I’m not art expert, but I could tell that he was well versed in painting a picture, constructing buildings (like his own art studio), clothing (all of his boots), and various other items that could be used in art. He could paint, use ceramics, and sculpt.

The problem was that he never got the respect of the art community. He thinks that is because he chose not to sell his paintings, and the community respects economy over talent. Whether that is true is not clear. Perhaps they saw him as a gimmick just like many would at Maestro Day. He challenges successfully recognized artists such as Andy Warhol and the Christos, all to no avail. Warhol passed away, and the Maestro thinks that given time, he would have given in. From what I know of Warhol, I sincerely doubt the Maestro would have been paid any mind.

He appears to be able to live thanks to an inheritance of some sort, and so he self-importantly lives the Van Gogh life, constantly reminding us of that. Even though Van Gogh had a benefactor in Theo, he lived in misery and desperation. The Maestro, with his massive arsenal, choice studio, and slick Cadillac lives with a smile on his face.

Film Rating: 6.5/10

The Maestro Rides Again, 2005

In this follow-up work, the Maestro shows more of his work, including his first set of boots, a piece of luggage that has the state of California and all its counties. He paints a series of famous landmarks, which for the documentary his subject is the Mission of San Gabriel. He wanted to paint the first McDonalds in Downey, but does a “drive by” painting because it is too dangerous a neighborhood for him to stand all day.

This time his inspiration is Howard Finster, famous artist who rendered many REM covers and was proficient with folk art cutouts. The Maestro makes his own version of cut outs, with popular figures like Chet Baker, Miles Davis, Howard Finster and unpopular figures like George W Bush, who the Maestro dubs “Inferior Man.” He is not a conservative cowboy. That much is clear.

Cinephiles should appreciate his artistic series on a number of films, such as a painting about Fitzcarraldo, although the painting makes it look to be more about Blank’s documentary about the project, Burden of Dreams since both Kinski and Herzog are in the frame. He also painted other Les Blank images, such as the polka film with Blank in the audience. He was clearly a Blank fan, but was that because of his respect for the man’s craft or to serve his own ego since he was a Blank subject. 5/10

The Maestro – Interview with Gaxiola in 2014. He thinks Blank hit the ‘high spots’ and the cowboy stuff and not as much the artist. He thinks the film portrayed him without any depth, and again laments that he thought of himself as a Van Gogh, but the art establishment did not want that. He said the process was frustrating because the filming took 10 years and Les Blank was not a guy with a plan. He just filmed. Blank pretends he’s not interested until you start doing something, and then he would turn on cameras.

He seems to regret the Cowboy caricature, and he especially complains when people call him out for “dressing” as a Cowboy, because it makes him feel like a phony. My question is, does he rustle cows?

He is not altogether proud of the film and complains some, but then catches himself and tries to sound grateful. He is happy that the “Art is a religion and not a business” was the principle theme and has on.

Art for Art’s Sake – This is a brief feature about the process of putting the film together. Chris Simon saw an ad about Maestro Day, decided to go and had a great time. During the show, Maestro mentions Burden of Dreams. Wow! He and Les were like two peas in a pod. Lots of films took five or more years, mostly to let the material develop, but also editing. Maestro is an example of one that took a long time.

They discuss the Christos incident, which I found very interesting. Blank was not happy with this situation because he thought Gaxiola wanted to deface Christo’s art by spraying paint on it with his gun as part of his challenge. They argued about it, and compromised by having Blank shoot the challenge as if Maestro is shooting the umbrellas, but he does not. There is even a disclaimer that “No Umbrellas Were Harmed in This Film.”

SWORN TO THE DRUM: A TRIBUTE TO FRANCISCO AGUABELLA, LES BLANK, 1995

It is fitting that the final documentary on the box set is of a musician, and more fitting that it’s of a fringe, obscure and culturally immigrated genre. Francisco Aguabella is a Cuban percussionist who plays Latin Jazz and Santeria music. He emigrated Cuba in 1957. Even though he never made his way back to the homeland, he has stuck to his roots and helped bring his culture and Afro-Cuban to the states.

This is not the type of drumming that people would think of after seeing Whiplash. It is almost in a different universe. When you see it being played onstage, it is doesn’t appear to be as impressive. Aguabella is one of many percussionists, and he seems to be doing less actual drumming, but he is actually the mastermind that determines the beat. He translates via his big drum to the other drummers and creates a conversation with the other drummers. The sum of the entire process is magic, and nobody would argue that drums are not an important, if not the most important, factor in Afro-Cuban music.

There is plenty of exposition about the music origins, Francisco’s personal history, and the way the music works. The cultural history is fascinating even if they race through it, but it is the images that are the most powerful. There are certain key images that are unforgettable, like when Aguabella is playing at a religious ceremony and the camera freezes at the moment when someone becomes “possessed” by the music.

The colors that are painted on his face represent different Gods. He us a devout Religious person, and that can be seen through his playing. Carlos Santana says that when they are playing, the walls begin to sweat. People are always dancing, sometimes energetically, sometimes hypnotically. Like a lot of the music that Blank portrays, it inspires people to move.

Film Rating: 9/10

A Master Percussionist – This feature has more background info on Aguabella. He was a master Jazz drummer, but could also play Santeria. Back then he was one of few that could play in the states, although now many can play due to the popularization here. Latin Jazz was his love, but he was at his most powerful during the Santeria ceremony. It was just powerful.

They didn’t film him talking about his origins in Cuba before the revolution, where he would carry huge bags of sugar. After revolution, he was afraid if he left he couldn’t come back. He was a remarkable man.

Les Blank, Always for Pleasure. Part Two.

This next trio of Les Blank documentaries fit together well. They are all about Cajun culture, with the first two about the rural and backwoods Creole population, with the boxset’s namesake documentary, Always for Pleasure, a narrative of the types of celebration that can only take place in New Orleans.

DRY WOOD, LES BLANK, 1973

Dry Wood features the Zydeco music of Clifton Chenier, although he is directly profiled in the sister film, Hot Pepper. Like with the prior documentaries, this is a meditative illustration of a mostly ignored yet fascinating culture.

Set in Mamou, Louisiana, Mardi Gras 1972, Dry Wood begins with a group of people in various, outlandish costumes, singing along to Zydeco music in Creole language. It is fitting for this trio of films, as they begin and end with celebration, albeit the latter is on a far grander scale.

In this picture, Les Blank does what he does best. He captures the character moments. The day after Mardi Gras, he shows the Catholic ceremony of people getting ash placed on their heads for Ash Wednesday. From there he shows people living their lives, whether that is a man digging ditches, catching frogs, or kids playing their own version of baseball with a cylindrically squared stick as a bat (not too dissimilar to the type of play that Mance Lipscomb reminisced about in A Well Spent Life.)

Like with many Blank films, there is not too much dialog, and there does not need to be. The first person that speaks directly to the camera and seems aware of being photographed is a gentleman talking about making his first violin, and how he used various natural items that could be found anywhere, either in the house or outside, and it worked. This was 15 minutes into the film, and Blank only features someone when they have something to say.

The latter portion is about food and entertainment, another reoccurring Blank theme. My favorite scene is an outdoor gathering at night, where a number of locals talk about the type of meat they prefer to eat, and what sort they absolutely will not eat. Their opinions are mixed on deer, armadillo and possum, but they ate whatever was being served on that evening heartily. They drank too, and that’s when the fun begins. As the night progresses, the men start dancing and then play fighting, falling down all alongside each other. These are grown men, but this is the type of roughhouse play behavior expected of most kids. It is the booze that binds them together, and they are absolutely plastered on this night, as they likely are on many nights. It speaks to Blank’s talents as a filmmaker that he was able to capture them so relaxed and in their element.

Some of Dry Wood is not for the faint of heart. The day after the men have their fun, they kill and butcher a hog, while the women prepare it. At one point they saw the snout off of the hog, and later it goes into a meat grinder to later become headcheese. A baffled youngster wonders, “is this what is in headcheese?” He doesn’t like the response, and won’t admit whether he liked it or not.

Film Rating: 8

Supplements:

A Cultural Celebration – Taylor Hackford gives another interview and talks about how culture is cuisine. It is first infused into food, and then into music. His piece is about both sister films, with Dry Wood being about the cuisine and Hot Pepper about the subsequent music. Hackford talks about how Blank was looking for the so called “golden moments” where people are captured with their guard down. One such example is the scene where the grown men are dancing around drunk, and there are many others

HOT PEPPER, LES BLANK, 1973

Blank goes back to the well with this follow-up documentary, which is a profile of Zydeco accordion musician and “King” Clifton Chenier. It begins with him playing a concert in Lafayette, Louisiana, and this is the music that scores the film. They cut back and forth between the concert and Louisiana life, like they do in Dry Wood. The great scenes are again when people are unaware or apathetic about the camera, and do their own thing. One cute scene has a girl playing by hanging around a street sign. There are other people that just walk by, minding their own business, some working on the railroad, some going about their day.

The best scenes are the landscapes captured with the Chenier music in the background. There is one sequence that shows a beautiful country sunset, followed by a dark night with the only visible object a pair of dim headlights. This is what Blank excels at, making the mundane appear magical.

Much of Chenier’s music is upbeat, but the most beautiful song, “Coming Home,” is peaceful and serene. It is a scene that Clifton wrote for his mother before she died, yet she unfortunately never was able to hear it. You can hear the emotion in his voice as the accordion slowly and poetically follows along. Blank focuses on landscape scenes for much of this somber scene and it becomes a meditation. We see sky scenes, birds flying, and a number of engrossing landscapes. It is easy to get carried away into this world.

While Hot Pepper has its moments, it is uneven and occasionally jarring, For example, it has a lady speaking frankly and randomly above her vagina parts. The major failing is with Chenier, who is not as captivating a subject as Lipscomb or Hopkins. The only time we see him away from the stage is when he is playing on the doorstep of a house, sitting with some friends, but he does not reveal much about himself or his world view. He just plays.

ALWAYS FOR PLEASURE, LES BLANK, 1978

As one subject says midway through this celebratory documentary, New Orleans is the “city that care forgot.” By that he means that is the last place in America where someone can truly be themselves be free. They are free to dance around in public, drink, sing, shake their body, chant, or do whatever they desire.

The film begins with a slow funeral march through the street. As Allen Toussaint puts it, the march to the funeral is slow and that’s when the mourning takes place. The way back is when people cut up. Life goes on, and people enjoy themselves. The band members are the main line, and they perform the somber music on the way up, and the upbeat, party music on the way back. The second line are the dancers and singers, who give their old friend a send off with spirit and revelry.

The majority of this documentary shows people partying in various ways. There are people drinking up a storm on St. Patrick’s Day, with overhead shots showing a sea of green. People laugh and sing along Bourbon Street, hooting and hollering, meandering through the street moving to the rhythm of the music.

A Les Blank documentary would not be complete without food, so he takes a break from the partying to show the staple meals of New Orleans, red beans and rice being made. One expert talks about the proper way to eat a crawfish. You shouldn’t break open the shell, but just bite off the head and squeeze the meat into your mouth.

The title cards share a bit of history. Many of these traditions originated with slaves. Initially the owners would let them have Sundays off of work to celebrate. Eventually that permission was curbed, but slaves would find ways to get outside and enjoy themselves. Mardi Gras was a free-for-all, and that was when all slaves were allowed to celebrate. Thus begun the tradition that continues today of yearlong merriment with the party of the year every May.

Always With Pleasure ends on a high point, with the wild, rousing traditions of Mardi Gras. People march in the street. He shows people with percussion instruments, singing and dancing. Some people are dressed up for the occasion, while others are dressed in regular clothes, having fun just being there and singing along. “Ooh-na-nay!” they chant as part of a call-and-response mantra as they march along.

The main attractions are the Big Chiefs, some in pink feathers, some in white, some in blue. They even show a young kid wearing an elaborate costume in white, probably having more fun than he’d ever have in his life. These are the Indians and they are serious about their Mardi Gras presentations. They make their own costumes anew every year, and destroy them afterward. They are also always trying to outdo the other tribes. In doing so, they entertain themselves and everyone around them. New Orleans, at least some of the time, is where “care truly forgot.”

Film Rating 9/10

Supplements:

Lagniappe – This is a short film of 25-minutes with additional footage that was cut out of Always for Pleasure. It begins with a street band marching through Bourbon Street to a predominately white crowd, which is contrasted with much of the main feature that showcased African-Americans. We see more of musicians, like Professor Longhair, who also appeared in the main feature, who plays the shit out of some piano. A singer and guitarist do a duet together, with racy lyrics like, “if you want to feel my thigh, you gotta go up high.” Finally, there are more shots of the Indians singing. There are never enough shots of the Indians.

Celebrating a City – Interview with Maureen Gosling, who did just about everything else on this project. During the shooting, they stayed with Michael P. Smith, who was a famous New Orleans photographer. He gave Blank a lot of ideas on where to shoot. Blank was more interested in the celebrations off the beaten path, which is probably why much of the Bourbon Street parties were cut out of the main film in favor of more time with the Indians. New Orleans has parades everywhere, and they only captured a small portion of them. On the day of Mardi Gras, they spent an exhausting 10-12 hours walking down the street with heavy equipment, getting as much coverage as possible, and practically collapsed afterward.

My favorite story was how they cooked red beans and rice for people involved with the film. They even did this for special screenings. They would cook the meal and fan the scent towards the filmgoers as they watched. Their reward was they got to eat it afterwards. Now that would be the ultimate way to experience New Orleans without actually being there.