Blog Archives

Criterion: Bottle Rocket, Wes Anderson, 1996

It would be unfair to only talk about Bottle Rocket as Wes Anderson’s first film, and how it planted the template from which his future style would grow. It technically was his first film and certain stylistic and performance elements would reoccur, but it feels to be more substantial than a first feature. Wes Anderson and the Wilson brothers were learning, certainly, but the real first feature was the short film a few years earlier. That was their low-budget, independent way of figuring things out, and that’s what gave them the attention and confidence to be trusted with a larger production. Bottle Rocket cost nearly $8 million dollars and had some influential and experienced people involved, notably producers James L. Brooks, Polly Platt, and actor James Caan.

It is fair to compare this alongside Anderson’s other works, and in my opinion, it rates rather highly. Anderson says in the ‘making of’ documentary that people usually have one of two responses to the movie – they either love or hate it. There isn’t much in between. I’m in the love it camp, and have been since I first saw it many years ago. I’ve already talked about my respectful ambivalence toward’s Wes Anderson in my Fantastic Mr. Fox write-up (all of the rest which will eventually be revisited), but it is worth repeating that the style of all of his films can be divisive. Sure, he’s a critical darling, and deservedly so, but some people find his quirky indie style to be unappealing. That has been me to a certain degree, but not with Bottle Rocket.

I think it is among his best films, somewhere around Fantastic Mr Fox, Rushmore and Grand Budapest Hotel.. On some days I might call it my favorite Wes Anderson.

Why do I like it so much? First off, Anderson is a phenomenal filmmaker, and this is apparent from throughout the feature debut, and to a certain degree with the short film. Of all his films, I think Dignan is the best-drawn character, and I will delve into him further in a moment. Even though the film is eccentric, compared to many of Anderson’s other works, it is more realistic. Sometimes in his later films he will take the quirkiness too far, such as with The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic and Darjeeling Limited, and they appear to be more of a fantasy world than reality. Bottle Rocket and also Rushmore are grounded in a lower class, youthful and naive reality, with two (three if you count Bob) lost souls trying to scrap together a place in this world.

Another strength of Bottle Rocket is the romantic element, which I think Anderson has only come close to replicating with Rushmore. The fact that Anthony falls for a hotel housekeeper speaks to his desperation and to his benevolence. Most housekeepers are invisible, even to the lower classes. It speaks for Anthony’s character that not only he recognizes her, but he pursues her in the kindest, gentlest way possible, yet is genuinely infatuated.

One of my favorite scenes in all of Anderson’s movies is the pool scene where the romance is effectuated. The scene is beautifully lit and the pool is a gorgeous shade of blue. The camera angles are not linear, but not disruptive either. The way the scene is shot lends to the awkwardness and uncertainty of the characters, and the satisfaction for both of them once they finally act on their feelings. The scene ends appropriately with Dignan interrupting them.

Dignan is the type of character that is easy to love and feel sorry for at the same time. He is ignorant, naïve, and not very self aware, but he is also charismatic and confident. He has qualities that everyone has to a certain degree, yet they are accentuated. He is like a more eccentric and less intelligent Max from Rushmore. He will say what he means and sometimes trample on others, but he will instantly back down when it comes to a confrontation. His most endearing characteristic is his optimism and glass half-full outlook on life. I will not spoil the ending, but the fact that he utters the line “We did it” triumphantly to Anthony and Bob, just sums up everything about him. He gives another great line while in the midst of a heist – “They’ll never catch me because I’m fucking innocent.” He gets the best lines in the movie, as he should, because he’s …. well, he’s just Dignan.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements:

Commentary with Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson – They can barely remember the movie because they made it so long ago, but they still share a number of good stories. They weren’t sure whether they would cast the Wilson brothers because they had little acting experience and wouldn’t give the project much panache. The producers were the ones who convinced them. Jim Brooks thought Luke had a Montgomery Clift feel.

It was interesting that they cut roughly 20-minutes of an action sequence. This was Bob’s pot plant being discovered by police and them running away, much of which is in the deleted scenes. The odd part is that the remainder of the movie has very little action save for the very end, yet they cut the scene that had a lot of action because it simply didn’t fit.

They talk about the disastrous test screenings, and how they thought their film was funny, but discovered later that “there was not a big laugh in the movie.” They remembered one incredibly positive comment card out of 500 from that first screening where most people walked out. Anderson coincidentally met the person who wrote the card later and he recognized her because he cherished that card and kept it.

The Making of Bottle Rocket – This is mostly a series of interviews from the participants, since not much footage exists from the actual shooting. Anderson and the Wilsons talk about how young they were and how little they knew, but others say they were more professional and confident on the set. Andrew Wilson, for instance, says that they play possum because they knew exactly what they were doing. Interestingly enough, they were making $700 a week and $100 per diem during the production. They were kids and had never earned this type of money before, so a lot of people accused them of milking the production time to keep getting paid. The jury is still out whether that was the case, but they at least established the slow pace at which they would develop films. Anderson has never been in a major hurry, and that has helped his films retain a sense of quality.

Bottle Rocket, 1994 – This is the short 13-minute film that was recognized at Sundance. There are many similarities to the movie, such as the stealing of the earrings, playing pinball, the book store heist, and many more. For a student film, they do a good job and I can understand why people saw enough promise to give them a feature. It also looks inexpensive. For instance, they don’t show the bookstore robbery. They just show the actors talking about it later.

Deleted scenes – You can see the amateurism of the filmmaking from the deleted scenes far more than anything else, and they were smart to delete them. They would have slowed the movie down with irrelevancy. The pot chase was a fun scene, but most others were just distractions.

Photos and Storyboards – The photos were from Laura Wilson and encompassed the feature and the short. These stills are more for the die hard fans.

Shafrazi Lectures, No. 1: Bottle Rocket – For a critical commentary, this one was disorganized and inarticulate. He says some things about the characters, but mostly looks at random scenes and comments on them. Most of his comments are not very insightful, such “I love that,” for one or “I don’t like that” for another.

Murita Cycles, 1978 – This is Barry Braverman’s documentary about his father Murray. Braverman was a collaborator and friend of the filmmakers and this early work inspired them. You can tell that they modeled some of their characters from Murray. He is quirky and soft-spoken, and reminds me of some of the Bill Murray characters in later films. He is sort of a hoarder entrepreneur, yet is unafraid of getting himself dirty. Like a lot of Anderson characters, he is endearing and refreshing despite his flaws.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Criterion: Sundays and Cybele

SUNDAYS AND CYBELE, SERGE BOURGUIGNON, 1962

One thing I love about Criterion is they manage to balance title releases based on popularity and credibility. Rather than just sticking to top selling auteurs for every release, they’ll often pull a movie out of obscurity and allow it to be rediscovered, even if that means it won’t sell as well as Ford or a Lynch. Sundays and Cybele is hardly obscure, having won international acclaim at the time of its release, including an Oscar win. Yet, for an early 1960s release during the height of the French New Wave, plenty of other films overshadow it. Unlike his contemporaries who enjoyed lengthy, prosperous careers, Serge Bourguignon mostly disappeared into obscurity, his career all but dead by the end of the decade.

Sundays and Cybele is almost the antithesis of a French New Wave film, which may explain why it is such an outlier in the movement. It is slower, more poetic, less spontaneous, and more deliberate. It has more in common with Bresson than Godard, and it dabbles into a darker and less fanciful theme than most would care to engage.

Pierre (Hardy Krüger) is a shell-shocked veteran of the Indochina War, racked with guilt for possibly killing a young girl civilian. He has amnesia and struggles with a return to ordinary life. His former nurse Madeline (Nicole Courcel) becomes his lover and caretaker, yet he his progress with her has limits. It’s through a chance encounter at a train station with Françoise/Cybèle (Patricia Gozzi) that he finds his anchor. She is a 12-year old girl, abandoned at the boarding school, basically an orphan, and he poses as her father to visit her every Sunday. What follows is a friendship and, in a unique way, a romance, yet does not quite reach the level of pedophilia.

The film is visually stunning, thanks to some unconventional shot selections and the camerawork of Henri Decaë (who oddly enough had made his career shooting New Wave films). Most of these shots were visual representation of the disconnection with society and the haziness within Pierre’s persona. For example, there’s one tracking shot that shows the reflection of the street through a vehicle side mirror. As the vehicle climbs a hill, we eventually see Pierre walking, and the shot continues with the driver getting out of the car. There is another excellent shot when Pierre is having lunch with Madeline and her friends, when he gets up and wipes a circle in the fogged up window, where two horse riders are interacting on the other side of a pond. Not only were these shots gorgeously photographed, but they were precisely choreographed. These were but two of many that likely took a lot of thinking and staging, and the execution resulted in a strikingly original looking film.

There are several motifs throughout the film, but the one that impressed me the most was the use of glass, mirrors, and how it interacted with the photography. Glass objects are used as props, and at one point in the lunch scene, the camera takes Pierre’s perspective as he looks at his companions through a wine glass, again showing his distorted worldview with filmic elements.

The relationship between Pierre and Cybele is complicated. He is continually infantilized. Even Cybèle playfully observes that “deep down you’re like a lost child.” She unmistakably loves him in a romantic way, at least as much as she understands of love at her age. His responses are affectionate, yet he stops short of vocally acknowledging her interpretation of their relationship. She is his conduit to his inner self, and he is possessive of her affections, yet is actual intentions are unclear the audience, as they likely are to himself. She daydreams of marrying him when she is 18 and he is 36, which might have happened if the relationship were able to progress. To further complicate matters, he finds himself romantically impotent towards Madeline. Cybèle is the one who fulfills him, while his lover leaves him empty.

Even though this is a gorgeous film with richly drawn characters, it has some storytelling problems getting to the final act. The film plods when Pierre disappears and Madeline recruits Bernard to help find him. The finale is temporally out of synch, as we learn of the outcome before we see it. While that results in an effective scene, with Madeline’s reaction seamlessly cutting to Cybèle’s, it is makes the ending less impactful and somewhat unsatisfying.

Film Rating: 7.5

Supplements:

Serge Bourguignon interview. Much of the time is spent discussing the film and it’s themes, but I thought the most interesting aspect of the interview was hearing him explain why his career ended. He seems to think it was due in large part to the jealousy of the New Wave filmmakers for his American success and the Oscar. It sounds like there were some disagreements, and he acknowledges that some of the problems may have been his own fault.

Patricia Gozzi interview. Her experience is also interesting because she was such a young actress, and this was her first significant role. She also disappeared from acting approximately a decade later, yet she does not give her reasons (I believe it was for marriage). Her relationship with Krüger was a close friendship, and that translated to the screen. I wonder if she grasped the taboo nature of their relationship during the filming. That’s another topic she doesn’t address.

Hardy Krüger interview. Krüger is undoubtedly the most successful of those involved with this project, having gone on to do major American pictures like Hatari, Flight of the Phoenix, and Barry Lyndon. He remembers the production fondly. Even though they initially wanted Steve McQueen in his role he made it his own and was proud of the movie and its success. He was living in Africa at the time of the Oscars, so had to learn of the win via a telegram, but the excitement was not lost on him.

Le sourire: This documentary short won the Palme d’Or and ultimately launched Bourguignon’s theatrical career. It is a 20-minute short about Buddhists in Burma. You can see here how his slower, poetic approach to filmmaking originated. The film displayed the physical beauty of the temples and the people, while conveying their spirituality and purity. Having lived in Thailand when I was younger, this was quite familiar to me. In a way it felt like a trip to the past, so my rating might be a little biased, but I absolutely loved the short.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Criterion: Macbeth

MACBETH, ROMAN POLANSKI, 1971

This entry will be a little different. I won’t try to establish and discuss the major themes of this work. Scholars, far smarter, more educated, and better read than I, have been exploring Shakespeare for centuries. Plenty of ink has been printed on the subject to Macbeth, and my take having is far from academic having read some of the play in High School and now seen interpretations from Polanski and Kurasawa. Instead I’ll look at this as a unique representation of the bard, and as a large-scale epic, which is truly unique compared to other Shakespeare adaptations.

Polanski’s take is far more accessible than most Shakespeare on film, and has more in common with Monty Python and the Holy Grail or Game of Throne than it does a traditional Olivier Shakespeare adaptation. It is a medieval epic on a grand scale with plenty of action, royal intrigue, brutality, and yes, even nudity (although not what you’d expect). The dialog is directly from Shakespeare, but it is spoken in a different manner. Rather than have the actors digress with poetic speeches, they use much of Shakespeare’s words as voiceover to show their interior dialog and establish their thoughts and motivations. As a result of these slight diversions, the material is more consumable and flows smoothly. It’s more engaging and less perplexing, yet it still isn’t dumbed down for a mainstream audience. It is distinctly Shakespeare, but presented through the lens of a young, trouble director in Polanski.

The elephant in the room is that this was Polanski’s first work after his wife and friend were savagely and brutally murdered by the Manson family a couple of summers ago. Some of the violent choices he made for this movie are curious given what he was dealing with. Some of the departures from the original are to show more violence. There is one scene in particular when a family gets slaughtered in their own home that had to have been inspired by the events of that fateful summer. You have to wonder whether this was a cathartic way of dealing with the tragedy. The one thing we can tell is that there is a personal edge that comes through the brutal telling of the story.

Despite his personal tragedies, this is a period of transition in the career of Polanski. He was already among the top directors at the time, having churned out a number of hits. Some of them were artistic (Repulsion, Cul-de-Sac), while he had also experimented with mainstream genre (Rosemary’s Baby). Macbeth was not only more literary than his previous works, but also his first attempt at an epic. He does quite a bit with a small budget, using elaborate, genuine costumes, glorious sets, and amazing cinematography. We can see here the filmmaker who would eventually make Tess and even The Pianist, many years later.

As a piece of art, Macbeth is up there with the best of the Shakespeare adaptations, and it’s a shame that few director’s (no offense to Branaugh) have been up to the task of putting together such an ambitious and daring treatment of the material since.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements:

Toll and Trouble: Making “Macbeth.” This new hour-long documentary touches on a lot of interesting subjects. One of which was how the film got made in the first place. No major studios were interested, so the surprising financier was Playboy. That led to a little bit of pressure and some stigma that would be added to the film, but also made it a little unique. Eventually they gave Roman plenty of artistic freedom. Also featured are Francesca Annis who played Lady Macbeth. She talks frankly about the mood on the set and her thoughts of doing nudity for the production. Martin Shaw talks at length about the project, and speaks about how Jon Finch came to be cast as Macbeth (he met Polanski on a plane), and how good he turned out.

Polanski Meets Macbeth: This documentary shows plenty of behind-the-scenes footage of the production, ranging from directing large scale acting scenes, to seeing how the cast and crew are fed (and hearing the complaints of the people who feed them.) This documentary isn’t enthralling, yet it is neat to see how much footage was captured from the shoot.

Dick Cavett Interview with Kenneth Tynan: This interview was conducted prior to Macbeth’s release, and most of the interview is not about the Polanski project. They discuss it briefly toward the end.

British Television “Acquarius”: Polanski and theater director Peter Coe discuss their Macbeth projects. The former is of course the Polanski epic, while the latter is “Black Macbeth” which couldn’t be anymore different.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

Criterion: Opening Night

OPENING NIGHT, JOHN CASSAVETES, 1977

At times while watching Opening Night, it felt like I was watching the ideological sequel to A Woman Under the Influence. Gena Rowlands again plays a woman going out of her mind, only this time it is not her immediate family that suffers, but the production staff of the play of which she is the star. Cassavetes explores her character a little deeper, focusing less on the peripheral characters, and more on her internal breakdown. We see what she sees, mostly from her perspective. She is primarily haunted by an autograph seeker who died outside of a playhouse, and sees images of this dead, young girl as she continues with the production.

It is probably unfair to compare the two movies despite the similarities, because Opening Night is more abstract and deeper in how it approaches its central theme, the aging of a famous actor – something certainly close to home in the real lives of Cassavetes and Rowlands. Age is the subject of the play, and it is overtly part of Rowlands’ hallucinations of this younger girl, who she at first feels sorrow for, which eventually transforms towards resentment. As she descends further into madness, her downfall has less to do with any feelings of guilt towards the girl’s death, and more as a wrath for her representation of youth. The character looks like a younger Rowlands, and as she rejects the script of a play that characterizes her as older, she takes out her wrath on this phantom youthful ideal.

If anything, age was too much of a central theme, and even if it was approached creatively, it was not portrayed with much subtlety. I felt that too much of the lengthy running time was dedicated to exploring this theme, but the message would have been just as clear with a lot less.

With the utmost respect for Cassavetes and his craft, and some people that I regard highly consider this his best work, but I had some problems with Opening Night. Part of this has to do with the heavy-handed treatment of aging. Another part was that I felt the independent nature of a Cassavetes production did some damage to this film. Sometimes answering to a producer can keep someone accountable with their ambition.

Realism went out the window, and I’m not referring to the hallucinations. The plot became unbelievable as the producers of the play continued to abide by someone who they could tell was losing it. I don’t expect they would have kept this person in the lead role and risk disaster during opening night. Or they would have delayed the open until they got the situation under control, resolved, and the star actress became comfortable with the material, which she clearly wasn’t. I also had problems with the final scene with Rowlands and Cassavetes playing off of each other, obviously improvising, and the audience gushing at them. The scene itself was entertaining simply because of the magnetism of two experienced actors. The problem was that the play did seem all over the place, and an actual audience would have trouble enjoying it. A real broadway audience would have problems with this play within a play. The final scene continues for awhile and expresses very little, and I feel the audience would have become impatient.

Film Rating: 5.5/10

Supplements:

Gena Rowlands and Ben Gazzara: There was a similar conversation after The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. It’s enjoyable to hear these two talk to each other and reflect. They discussed how disappointing it was that this movie essentially flopped after Bookie did as well, and that the final scene was mostly improvised.

Al Ruban: This was a short interview yet was one of the more revealing interviews of the entire disc. He said that Cassavetes gave his crew almost carte blanch to work based on their own interpretations of the script. He also revealed that John could be difficult to work with, and during one period of the shoot they ran out of money and had to go on hiatus for two weeks. Ruban had a falling out with Cassavetes and considered walking off, but Gazzara convined him to finish his work.

Criterion Rating: 5/10

Criterion: The Innocents

THE INNOCENTS, JACK CLAYTON, 1961

My first exposure to Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw was as a young teen. It scared the daylights out of me, and I never really forgot it. Jack Clayton also experienced the material as a youngster, and was likely scared just like me, but he could identify with the children in different ways – the sense of loneliness, abandonment, and that is part of the reason the material remained special for him, and eventually he would be responsible for the best visual representation of the novel.

The Innocents is, more than any film I’ve yet seen, the quintessential gothic movie. Of course a lot of that is due to the James source material and Truman Capote’s eerie script, but most of it has to do with the look and feel. It was not just Freddie Francis’ brilliant cinemascope camerawork, but also the clever editing, the mise en scene complete with a distinctly gothic floral motif, the dissolves between shots, and of course the location and the Victorian-style house.

The performance salso deserve some accolades. While Deborah Kerr is the focal point that carries both the plot and the ambiguity, and she is amazing, I was also impressed by the children. It was interesting to hear that much of the ghost-story plot was withheld from them so that it would not impact their performance, so perhaps Clayton deserves just as much credit. Pamela Franklin is brilliant as Flora, in an understated and fragile role, but Martin Stephen’s Miles really stole the show and sold the possibility of what was taking place in the house and/or in Miss Giddens’ head. The scenes where Stephens and Kerr interact directly were particularly exceptional. He played wise beyond his years, and was able to hold his own when discussing and debating the goings on with Miss Giddens. His intelligent, knowing looks made clear that at the very least, he had some behavioral problems, and was at worst possessed by a ghost.

There are two readings of the film, and they were intentionally ambiguous. I cannot continue without spoiling the film, so please stop reading from here if you have not seen it.

The question is whether the ghosts are present or whether they are a figment of Miss Giddens’ imagination. There are plenty of arguments scattered throughout the film, although upon repeated viewings, there does appear to be more evidence of the latter theory. She notices the apparitions before the children, or at least as much as they will admit, and reacts before they are shown on screen. The children continually seem oblivious to what she is observing, and she implants thoughts and feelings into their minds that do not always seem rational.

Another piece of evidence that suggests the ghosts are real is that Giddens sees Miss Jessel at the lake before learning that’s where she committed suicide. Also, as noted, Miles is a clever human being, and the best evidence for the real apparitions is at the very end when he lashes out at Giddens, with the ghostly Peter Quint appearing in the window engaged in laughter at the tirade. Then, as she sees Quint clearly just before the child’s last breath, there is a shot of him with a momentary look of acknowledgement. Had he finally seen the ghost? Was he indeed possessed and this act of exorcism was his undoing? A third theory could also be explored, that Giddens was possessed by Jessel, who wanted her revenge on Quint and achieved it during the final scene. It was brilliant of Clayton to leave this ambiguity intact.

I cannot say enough about the film’s quality, especially the lighting. The highlight for me was the dream sequence about an hour into the film, which consists of a multitude of dissolved sequences, ranging from flocks of pigeons, dancing with the music box, or praying hands like opening and closing of the film. Whether they were real or imaged by Miss Giddens does not take away from their brilliance.

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements:

Audio Commentary: Christopher Frayling, a cultural historian, brings a lot of detail from the Henry James novel, the adapted play of [i]The Innocents[/i] and stories from the set. He also does a good job at pointing out the filmic elements that are used to support the different readings of the film.

Introduction: Frayling again introduces the film by visiting some of the locations of the shoot. The remainder is mostly repeated in the commentary, with a few scant unique details.

John Bailey Interview: Bailey is an accomplished Director of Photography, and he discusses Freddie Francis’ techniques in detail. The technical limitations of the Cinemascope cameras give more appreciation with the final product given what Francis had to work with. He made the absolute most of it, and the film would be completely different with another aspect ratio or a different DP.

Making Of: This is a newly edited series of interviews from 2006 with Freddie Francis, editor Jim Clark, and script supervisor Pamela Mann Francis. These are all interesting in their own right. Francis has the least screen time, but he is mentioned constantly by Clark and Francis. They also credit Capote’s contribution and Clayton’s vision. The interviews are mixed with HD clips from the 4k restoration and are a suitable accompaniment.

Criterion Rating: 9.5/10

Criterion: Eraserhead

ERASERHEAD, DAVID LYNCH, 1977

Some might call David Lynch a weird dude; others would call him a visionary artist. To me, he’s a little of both, and I can take him or leave him. Some of his work leaves me cold, like Lost Highway[, while I consider others to be masterpieces, most notably Mulholland Drive, and also the under appreciated Inland Empire. Eraserhead is somewhere in between. It is something I respect far more than I like, and it represents a starting point for one of the most inventive and creative cinematic minds of the modern era.

One thing that is remarkable is that this film was made at all. That’s one reason why I love these Criterion releases. Every film has a story behind the story, and Criterion teaches as much about the process of getting it to screen as it does the images as art. Eraserhead took a long time to get made, and the project came about as a happy accident when Lynch nearly had a falling out with AFI. They were giving filmmakers a lot of rope, and they pretty much left him alone and did his thing. The final product, to me, is not perfect, but it is of unquestionably high quality, and not something you’d expect from someone who had previously directed a handful of experimental shorts.

The movie itself doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. Lynch acknowledges as much and refuses to share his interpretation. I actually really admire that. As anyone who has been in a good English, Film or Art History course can attest, the creator’s original intent has very little to do with how people interpret and understand the film. In some of the marathon discussions in which I’ve participated, we have deconstructed the piece of art far far beyond the creator’s vision or intent, and that’s what makes it beautiful. Something that can be a lot of things for a lot of different people has power, and that’s why a films like Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive can take hold.

It doesn’t take a lot of searching to find popular theories on the Internet. Here’s one. Here’s another. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. You could scour blogs and discussion boards for hours just reading different interpretations. Lynch likened the film to a Rorschach test, implying that the way people interpret the film says more about them.

Aside from enjoying it as a piece of entertainment a few times, I cannot say that I’ve gained much more understanding of it, but I have picked up on several themes and motifs, just like everyone else. The sexual symbolism is overt, with the spermatozoa-like objects (for lack of a better word) popping up on occasion. In one scene Henry finds them all over the bed he is sharing with his girlfriend/wife. Could that be sexual guilty? We don’t know. Fatherhood is another key theme, as embodied by the freaky, mutated baby, that I’d still rather not know what it really was. On this recent viewing, I picked up on some commentary on modernity and technology. This is expressed all throughout the movie, most notably through the constant humming of the machinery. There are other moments where it comes into play, such as when Henry’s girlfriend’s father marvels at the smaller-sized chickens, which he proudly exclaims are new! And of course those chickens foreshadow the eventual baby, so if the message is of modernity, it is interwoven with the pressures of the nuclear family.

For such an independent and low budget film, it is technically brilliant. One element that stands out to me is the sound design — which is often a constant hum. The black-and-white cinematography looks terrific, especially on this Blu-Ray (I had previously seen this on VHS or streaming).

There are a lot of different avenues to take when interpreting the film, and there really is no wrong answer. David Lynch isn’t going to take out his red pen to anyone’s conclusion. He’s just proud that we’re still thinking about it.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements:

David Lynch Shorts: The majority of these are from early in Lynch’s career, prior to the release of Eraserhead. Some of them were created concurrently with that project since it took so long. The only exception is his one-minute contribution to Lumière and Company, using the same century-old equipment that the early pioneers of film used.

If Lynch hadn’t become the filmmaker that he is today, these most likely would not have seen the light of day. They are clearly amateur filmmaking, yet they are experimental and show glimpses of what would become his style. That’s not to say they are not good on their own right. For what are essentially student films, these are high quality. These were part of the reason AFI favored him and gave him freedom to make a feature.

And yes, as you might expect from Lynch, the shorts are weird. The Amputee has a double amputee transcribing a letter while her wounds are being tended to by a nurse. The Grandmother is about a bed-wetting child who grows some sort of object on his bed that births his an old lady. This was the longest and best of the shorts. Most of them mix crude animation with live action, which gives them an added surrealism. All of the shorts are worth watching, especially for Lynch fans.

Documentaries and Interviews: The remainder of the supplements are arranged by the year in which they were released, with no explanation. You just click the year and see what happens, which is a very Lynchian format. These were all interesting in their own right. I enjoyed the interview from the set that was conducted after the release about the time the film was achieving cult status off as a midnight movie. Lynch was frank about his methods, but silent about his meanings. That’s a silence he would keep throughout his entire career. There was another documentary that was basically Lynch talking into a microphone about the process. This one was the least interesting, even if he gave the most information. I particularly enjoyed the most recent documentary, which features some of the actors and crew members, which most likely was recorded just for this release.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

Criterion: All That Jazz, 1979

ALL THAT JAZZ, BOB FOSSE, 1979

What separates All That Jazz from most musicals, is the level of honesty and authenticity. The musical numbers are all ways of expressing reality in an entertaining and artistic fashion, whether they are about the process and mechanics of putting together a Broadway music, or about one’s own mortality. Fosse’s mostly-autobiographical tale brings us into his world, the theatrical and directorial world, and uses that as a means to another world. More on that latter world in a moment.

The theater world is the one that Fosse knows the best, and he portrays it as a true insider. It begins with the cattle call, an arduous and brutal ordeal. The sequence goes on for a long time, nearly in a documentary style with clever editing to show the magnitude of performances that take place. George Benson’s version of “On Broadway” plays, reminding us what the stakes are. One of the dancers says he’s willing to change his given name (Autumn) if he gets the job. A job in a Gideon (or Fosse) production could make a career.

There are other theater sequences that are particularly effective. This was my third viewing, and one that struck me this time was the audition sequence with Victoria, who Joe had recently taken as a lover. Some may think that entitles her to special treatment, yet she gets none. She lacks in the talent department, so Joe pushes and pushes her away from mediocrity. You can see the pain on her face with every new attempt, and you sympathize when she thinks about quitting. This probably happens all the time in the theater world. She doesn’t quit and after a number of repetitions and being drenched in sweat, she gets the nod of modest acknowledgement. Gideon says that a take is better, and a sense of relief passes through her exhausted face. It was a nice character moment, performed well by the actress.

The other music pieces are part of Joe’s world. The adult-themed airplane number is performed as a dress rehearsal for the producers, but it takes a life of its own. It shows the director’s brilliance, but also his bravado. He’s not afraid to push the envelope, and the number is a reflection of how he lives – sex, drugs, and smoking. Another musical number is performed by his girlfriend and daughter, and is a great way of developing the character relationships in an entertaining and touching manner.

The other dance numbers were also part of Joe’s world, but not the same world. This world is just as open and honest, maybe more so, and they again show how Joe/Bob will go to depths that most filmmakers won’t.

Be warned, the remainder of this summary is going to be full of spoilers. This movie cannot really be discussed without referencing the ending.

Even though the dance numbers are entertaining and even fun, they are a contrast with the harsh reality of what Joe is facing. This is shown in graphic detail during the heart surgery, where they show the medical procedure happen – something I had never seen prior to this movie, and never expected to see.

That takes the movie to a different level. While in the hospital, Joe has a musical hallucination, which talks about how much he has done wrong, how he has failed. His decisions have led him to this point, with a fractured marriage, a stressful career, and literally, a breaking heart.

The final scene is pure brilliance. It is Joe saying goodbye to the world, including his professional peers, his family, even his enemies. The lyrics “Bye bye life. Bye bye bappiness. “ are dark, morbid, yet they are celebrational. “I think I’m going to die. Bye bye my life, goodbye.” Even though the movie clearly is leading up to the finality of Joe’s life, the harsh, abrupt ending is still shocking. It is still bold. It is still amazing. Even though the prior ten minutes were full of smiles and festivity, the stark reality is that you will be zipped up into a body bag.

Phenomenal movie. I’ve long called it my favorite musical ever, and that was cemented with yet another viewing.

Film Rating: 9.5/10

Supplements:

There are a ton of supplements, so I’ll give an abbreviated survey here.

Commentaries: There is one full commentary with Alan Heim, the editor, and Roy Scheider, the lead actor. Even with the shorter duration, Scheider’s is the more interesting, as is to be expected. Heim’s is good too, but there is already a featurette about the editing on the disc that is more effective. One thing that’s surprising from both commentaries is about Fosse’s take on the autobiographical details. It seems that he minimized the fact that it was based on his own experiences, yet they were undeniably him. Heim points out that the address on the medications was Fosse’s address, and he would refer to the lead character as “you” when addressing Fosse, which the director didn’t like.

Ann Reinking and Erzsebet Foldi: The actresses that played the girlfriend and daughter have a good rapport as they reminisce about their experience. The young actress had no idea of the scale of the movie when she was doing it, and it was something hearing her talk about seeing people lined up around the block.

TV Appearances: There are three of these; one with Fosse and Agnes de Mille, and the other two with Fosse solo. It’s weird seeing Gene Shalit doing an interview. I’m not a fan, but Fosse makes for an interesting subject.

Featurettes: There are several. My favorite was on the editing, which sort of negated Heim’s commentary. There were others about the music, on-set footage, and even one on the making of George Benson’s “On Broadway.”

Documentary: This is short by Criterion standards, but long considering everything else on the disc. It is roughly thirty minutes and has several interviews with people involved with the production, including Sandahl Bergman, who was flown in just three days before her scene and had to learn a complicated dance routine.

Between the quality of the movie, restoration, and the extensive features, this is so far the best Criterion release of the year.

Criterion Rating: 10/10

Criterion: The Essential Jacques Demy

THE ESSENTIAL JACQUES DEMY, 2014

This is the first completed box set for this blog, although there should be another one following pretty closely behind. This was a good one to start with. Going in, I had limited exposure to Demy, and wasn’t a huge fan of what I saw. Even though this set only includes the ‘Essential’ titles, it’s the best representation of his work, and with the shorts included, I felt that I had seen the development and evolution of style.

Even though I wouldn’t call any of his films masterpieces, I closed this set having a lot more respect for his craft. He went to places that other filmmakers wouldn’t go, and did some things that were truly original. I really like that his film universe had some connectivity, with reoccurring characters, motifs, and references to other films in the mise-en-scene. This would not be as easy to pick up if you watched the films individually over a longer span of time.

There are a couple of titles omitted that I wanted to see, especially Model Shop. My expectations are not high, but it seems to fit into the Demy universe since it is a sequel to Lola. Since the Demy family was so involved in this project, I am hopeful that Criterion will work on some of these other titles as standalone releases. On that note, I’m praying for an upgrade of Varda’s 4-films. The fact that this set was so comprehensive and she was heavily involved, I’d say it is a strong possibility.

Aside from Lola, the restorations were all impressive. Many of the discs had a short restoration supplement, and it was neat to see them remove blemishes as they found them. Lola’s restoration was poor, but I know that they had problems getting a workable master print. Since it was his debut feature film and it set the stage for so much of his later work, it had to be included regardless of the quality.

As for my impression of Demy, as mentioned, it improved. Musicals are my blind spot, but I found myself enjoying The Umbrellas of Cherbourg far more on this new visit, and I appreciated The Young Girls of Rochefort. As I progressed further into the set, I found myself appreciating Lola and Bay of Angels a little more, and will enjoy revisiting them at a later date. Donkey Skin was disappointing. While Une chambre en ville didn’t measure up to it’s stylistic sister, it was surprisingly effective, and it was refreshing to see Demy push beyond the boundaries he set for himself.

There were no commentaries on any discs. While that was disappointing, the vast number of supplements almost made up for it. I appreciated the two Varda documentaries a great deal. In fact, her The World of Jacques Demy is my favorite film of the entire set. I missed a lot of the critical examinations on the earlier discs, but was pleased to view James Quandt’s A-Z evaluation. His essay and Varda’s documentary were on the final disc, and that punctuated the set extremely well.

Here are all of the films:

Lola

Bay of Angels

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

The Young Girls of Rochefort

Donkey Skin

Une chambre en ville

Box Set Rating: 8.5

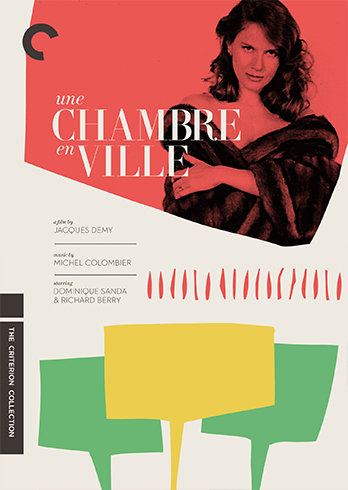

Criterion: Une chambre en ville

UNE CHAMBRE EN VILLE, JACQUES DEMY, 1982

After an opening strikers versus police scene that seems yanked from the Les Miserablés play (it wasn’t), the camera cranes up to an overlooking room with a baroness looking down at the commotion. After the conflict dies down, the baroness speaks with her boarder, who happens to be one of the strikers.

Strike that. She doesn’t speak, she sings, and he sings back. The wallpaper is a blood red, which matches her outfit. Immediately this scene recalls The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. It may be unfair to compare the two films, but Demy clearly intended to use the same style to tell this new story, and there are parallels with both films, albeit with a far different tone. Every line is sung, wardrobes and sets have matching colors, and so on.

As a musical, Une Chambre is no comparison to Umbrellas. The missing ingredient is Michel Legrand. I’m not sure why his collaboration with Demy didn’t continue, possibly because of the time commitment as he was a busy man at the time. Either way, his presence is sorely missed in this format. Michel Colombier is the replacement, and while he has put together a decent career scoring films, the only other thing he has in common with Legrand is the first name. His music in this film is uninspired and the sung dialogue doesn’t fit into the narrative as snugly as Umbrellas. Without Legrand, I wish they would have chose to let the actors speak rather than sing (or lip-synch). The intensely dramatic script could have made for a much better acting vehicle. Alas, that is not Demy’s style.

From the first ten minutes as the two characters sing the exposition to each other, I was prepared to dislike this film. It was immediately clear that it was trying to be another Umbrellas, and it was also clear that this was anything but. It took some time to introduce the characters and get the narrative rolling, but eventually I found myself taken in. While the music was lacking, everything else was vintage Demy. The costumes, set design and wallpaper did compare respectfully with Umbrellas. I particularly liked the scene with Edith and Guilbaud in his room, with the earthy colors of yellow and brown. These are colors that aren’t bright or flamboyant enough for Umbrellas, but they fit better with the darker story in Une Chambre.

Speaking of dark, when I reviewed Umbrellas, I mentioned how the ending was bittersweet, yet it manages to leave us on a high note. Aside from that, it is bright and bubbly despite being about a romance interrupted by the Algerian War. Une Chambre has a similarly dour premise, with a romance happening at the same time as a 1955 worker’s strike, but this is not bubble gum and butterflies. We know that when Edith and her husband Edmond first fight and the result is domestic violence. Later when Edmond confronts Edith’s mother, the baroness, he threatens to kill both Edith and her lover, if his suspicions of adultery are correct. Edith wears a fur overcoat with nothing underneath and she is bold enough to share the mystery underneath, which is an act far too seedy for the characters of Umbrellas, or any other Demy film for that matter.

I will not spoil how this plays out because it is worth watching. I’ll just say that it lives up to the dark foreshadowing. Compared with Umbrellas, Une Chambre has more grisly violence, stark sexuality, and the characters are not nearly as likeable, but the payoff is daring and not something you would expect from Demy’s universe.

Film Rating: 6.5

Supplements:

There are a handful of supplements on this disc, such as a retrospective and a couple of interviews, but I’m going to ignore those and focus on the two big ones, which happen to be the best supplements in the entire box set.

The World of Jacques Demy: Agnes Varda is an excellent documentarian, but none of her works is nearly as personal as this one. Created within years of her husband’s death, this is a retrospective and love letter of his entire body of work, including all of the inclusions in this set and other notable films like Model Shop and his final film, Three Seats for the 26th. It features Varda and family to a certain degree, but the most powerful sequences are three young girls who are simply fans of Demy. One of them reads a lovely letter she wrote to the director, thanking him for giving her life beauty and inspiration. The others felt the same, and they shared personal stories of how they grew up to Demy, how much they adored him and his work, and how they were left empty with his loss. Neither Varda nor any of his two children talk about his death, but they don’t have to. These three girls say enough.

Jacques Demy, A to Z: Film Critic James Quandt narrates this Criterion-produced visual essay about Demy’s body of work. He uses the alphabet to track Demy’s career, talking about the people who inspired him, motifs in his work, characters, and especially his family. With the letter B, he mentions Robert Bresson. Quandt also did the excellent commentary for Bresson’s Pickpocket, so he knows what he’s talking about. My first reaction when I saw Bresson’s name was that the two filmmakers have little in common with each other. Bresson is austerity while Demy is an eruption of style. Yet, Quandt still demonstrates a number of similarities that I had missed. Many of the male characters in Demy’s world are quiet, austere and understated, especially in his first two black and white films. Quandt parallels these characters with Bresson’s Michel and shows certain Demy scenes that were directly inspired by Bresson scenes. Near the end we get V for Varda, which is the most fitting. Oddly enough, they never worked together and they convey distinctly different styes and tones, but they complement each other and are forever intertwined. Finally, we have Varda and the Demy family to thank for putting this box set together and letting us experience Demy through their eyes.

On the strength of these two supplements, this is the best disc in the entire box set. Also note that The Young Girls of Rochefort is included in the DVD version.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Criterion: Donkey Skin

DONKEY SKIN, JACQUES DEMY, 1970

After watching two New Wave-ish films, and the two arguably most popular French musicals of all time, the last thing I expected was a surrealistic and unusual fairy tale. It is based on one of French Author Charles Perrault’s (Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty) lesser-known fairy tales, and is nearly a reverse Beauty and the Beast, which was not a Perrault work.

The tale begins with a king losing his fair wife and promising to not re-marry any princess that is not as lovely as her. This seems to be a typical and benign fairy tale premise until it takes a wide left turn. After reviewing the available princesses, he finds that none are worthy of the vow. Finally he realizes that there is one princess that he has forgotten to consider, his own daughter, played by Catherine Deneuve. He decides he must marry her. She isn’t opposed to the idea since she loves her father, but for some reason it doesn’t feel right. She demands that specific colored dresses be made for her, which the king obliges, until she finally requests a dress made out of the hide of a Donkey that, umm, defecates jewels. The king also obliges, and she uses this skin as a disguise to escape.

If that doesn’t sound weird enough, much of the rest of the film has Deneuve traipsing around with a Donkey head on top of her, looking ridiculously silly. On top of that, she encounters a kingdom that is obsessed with the color red. Everything is painted red, including the horses. The fairy tale aspect reminded me in a way of Louis Malle’s Black Moon, albeit with a clearer narrative and without the nudity. To my surprise, I found in the supplements that Demy intended this to be a children’s film, and he said that the incestual content would not seem unusual to young children because they naturally love their parents. I’m no prude, but I wouldn’t show my children a movie that even touches on them having a relationship with their parents, but maybe he is right that a child would miss this taboo. It’s difficult to put yourself in that position as an adult.

While this one doesn’t exactly fit tightly into the already established Demy oeuvre, it contains many elements that are familiar from his earlier films. I wouldn’t call this a musical, but it does contain a few Michel Legrand songs, which the actors sing in the same manner as Umbrellas and Rochefort, clearly lip-synching. The use of color and attention to detail is also Demy-esque. This is the case in the first palace, but it really stands out in the latter kingdom with the strong red color scheme. The costumes are also fantastic, and overall this is a technically accomplished film.

The problem is everything else. This does not quite work as a children’s fairy tale, and the reverse Beauty and the Beast plot is mundane and lazy. Some scenes go on for far too long, such as when the king is reviewing princesses, or later when the prince is trying to fit a ring on a maiden’s finger. It seems that Demy meant this as a commercial work without saying much. I’d say he failed on that level, yet still managed to put together a visual feast.

Film Rating: 4.5/10

Supplements:

Pour Le Cinema: This French TV program contained set interviews with Demy, Deneuve, Marais and others. This is the supplement that has Demy talking about how the children would not pick up on the incest theme. Aside from that, most of it was light and promotional, with the participants talking about how much they liked working on the film.

Donkey Skin Illustrated: This was rather interesting. They showed sketches, drawings and paintings inspired by the story. The best ones were those of the princess wearing her donkey skin. Many of them were the way that Demy portrayed it on screen.

2008 Discussion: This is a round table discussion with a critic, psychoanalyst, and literary buff about the film and it’s themes. While I said above that the film said very little, they brought out a few themes that I had missed, like the theme of liberation that embodied hippie generation of the time.

Demy AFI Interview: This was an audio recording at AFI, which I didn’t listen to in its entirety. In the parts I listened to, they talked about the process. Unlike a lot of other lighter interviews (like the French TV one), the AFI asks good questions about the filmic elements. It seems like an interesting interview.

Criterion Rating: 5.5/10