Blog Archives

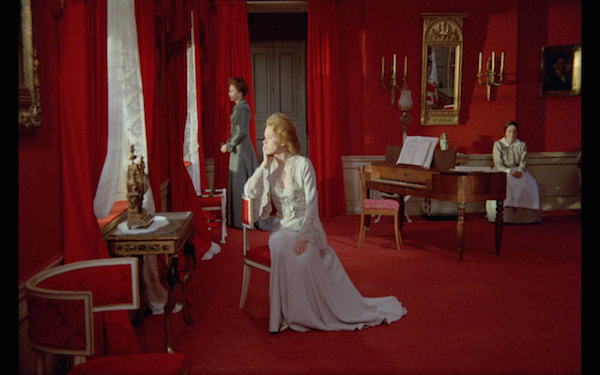

Cries and Whispers, 1972, Ingmar Bergman

By 1972, Bergman was already established as one of the titans of international art cinema. He had won several awards at Cannes and been nominated for two Academy Awards (he would eventually be nominated for 9, including three for this film). Cries and Whispers is not a film that could be made by anyone. It could not have been made by Ingmar in his younger years. It could be seen as a spiritual sequel to Persona, which was really his first foray intro surrealism and immersive, abstract character exploration. Cries and Whispers does not share many thematic or plot elements with this predecessor, but it does utilize the supernatural and it explores these four characters nearly as deeply as the two (or one?) in Persona.

Another similarity between this and Persona is the visual canvas. Persona was in black and white, but I think of it as starkly black and starkly white, almost to the point where it has the same effect as a color film. Cries and Whispers is a color film, but it is nearly a red and white film. The reds are stark and stunning, while the whites are a contrast, just like the whites were in Persona. The colors are visual motifs as well, as red signifies death, mutilation, and white represents the innocence of a lost and nearly forgotten childhood. Sven Nykvist rightfully won an Oscar for his work, and Bergman and crew deserve praise for creating such a visually remarkable red-and-white world.

The color of red is used most effectively for the scene transitions. At the end of a scene, the image dissolves into a red canvas, which gives it a surreal quality. It is a continual reminder of the central theme of death, as Agnes fights her battle with uterine cancer. Sometimes Bergman freezes in the middle of the dissolve, holding on the blood red screen to give us time to ponder and process the meaning of the scene. These transitions and the slight deviations with each one heightens the impact of the color red. I can think of many movies that have used a single color to dictate the theme, some of which are done well (Kieslowski’s Red for example), but none that used it to this extreme, creating what is basically a red and white film.

Please be warned that from here on our I will be delving into spoiler territory.

Harriet Andersson as Agnes gives the most memorable and challenging performance as she tries to cope with the pain and her imminent, unavoidable death. The anguish on her face is heartbreaking and convincing. Much of her performance is given in grunts and grimaces. She is at her most vocal at the very end of the film, but this is after she has passed and the pain has left her. Only the loneliness and the yearning for comfort remains. She seeks solace from her two sisters, yet receives it only from her housemaid Anna (Kari Sylwan) in an unusual yet effective manner.

The sisters, Maria (Liv Ullmann) and Karin (Ingrid Thulin) are complicated characters, at times polar opposite from each other, yet there is some grey (or red?) area in between. To her sisters, Karin is stoic and stubborn, refusing and being repulsed by intimate contact. Maria is affectionate and compassionate, yet she is unscrupulous, making out with the doctor watching over Agnes. In flashback we see Maria and the doctor having an affair, which results in her husband attempting suicide. Karin also flashes back, but her memory is of fidelity and mutilation. She says “nothing but a web of lies” as she abuses herself with broken glass and then exhibits a grisly scene for her stunned husband.

At Agnes’ funeral, the priest says that they had many talks and her faith was stronger than his. Is this why she is able to come back? This is never explained, but the ensuing revisitation with Anna and the sisters has differing results. Maria, who was affectionate to Agnes in life, rejects her in death. Karin also rejects and hates her resurrected sister. Again, the only character that gives her any comfort is Anna, yet the living relatives treat her with scorn and dismiss her as if she was a piece of trash.

The film can be interpreted a number of ways. It speaks to the intimacy (or lack thereof) of family, and how familial love and companionship is fleeting and unobtainable in later life and especially in death. It speaks to the wickedness of the upper class, and how true camaraderie and goodness comes from those that are not clouded by a privileged upbringing. It also says that personal relationships are ultimately rooted in selfishness. With their husbands and other sisters, the sisters care only for what they receive. The same is true about Agnes, who we learn little about, but she is also selfish for intimacy and companionship. The only true altruistic and benevolent character is Anna. She pledges to care for Agnes in life and in death with no financial recompense. At least Maria, who despite her flaws is the most considerate of the other primary characters, and gives Anna a little something to help. Maybe there is hope for humanity yet.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Bergman Introduction: 2003 on the Island of Fårö.

This project came about in winter on the island. It was melanchology time for him because he had just been broken up with someone. He was lonely with only a Dachshund to keep him company. He had an image of a room completely in red. He believes that if the image persists, you should keep writing.

Harriet Andersson – 2012 Stockholm interview with Peter Cowie.

This was just like the interview on the Summer with Monika disc, and was probably recorded in the same session. Harriet was again very animated and descriptive. She is a great interview at an older age.

It had been 10 years since she had worked with Ingmar. At first she rejected the part because it was too difficult. He said, “Don’t give me that load of crap,” and she took it.

The castle set was wonderful. They had offices downstairs. The red rooms were the studio on the main floor. The floor above was for make-up and wardrobe. Ingmar had said the red room resembled the inside of the womb. Andresson: “Well he says things.” “He like to make small stories.” She implies that he is telling a tale.

They kept her awake at night and that made her look tired. The death scenes were an imitation of her father, which she witnessed. He had a terrible death. She has trouble watching the film now because of that memory.

On-set Footage Silent color footage with audio commentary from Peter Cowie.

This is the highlight of the disc. They have quite a bit of silent behind the scenes footage that includes the set-up, press conference, actresses on location in and out of the house, the cast and crew being fed, editing of the film, rehearsals, and so forth. It is a wealth of material and Cowie gives numerous factoids on the film just by talking over the images. This was almost as satisfying as a good audio commentary.

They talk a great deal about the playwright Strindberg. He had spent summers at the manor that they used as a boy and took inspiration of Miss Julie from lady of the manor. Bergman had adapted Strindberg plays for stage, but never for film. One interesting point is that Bergman’s films were not very popular in his home country, but his Strinberg plays were exceptionally popular.

Ingmar Bergman Reflections on Life, Death and Love: 1999 television interview with Erland Josephson.

This is another enjoyable interview. They do not talk about the films so much as they do personal lives, loves, relationships, and various other topics. Bergman is surprisingly candid.

They talk about children. They both have quite a few (Bergman has nine). Bergman talks about apologizing to one of his children for being a terrible father, when the son says that he hasn’t been a father at all. They all get together every year at Fårö Island and the children have maintained good relationships. None of his children were planned. “They were all love children.”

The women lasted about 5 years until he found a new one, and then he found Ingrid, and then she died. When she decided to marry him, “all other traffic ceased.” He was truly in love. He is friendly with all the other girls that he was ever with, and many (including Liv and Harriet) became part of his acting stable. Elrand points out that all the bitterness subsides over time. With Ingrid he had a close relationship, and he has reverted to solitude now that she’s gone.

They talk about death and the inevitability, and how Ingmar doesn’t fear it so much but Elrand does. Of course he talks about Ingrid and how he planned to leave Fårö to her, but her passing happened and it crushed him. You can tell that his life was still devastated by it even all those years later.

On Solace: Video Essay from :kogodana:.

This is an interesting essay, unlike most on Criterion discs. It uses images and text well, especially the red title cards with white text.

The concept of the three movements is abstract to a degree, and it is easier to watch than for me to explain it here. Basically he says that there are three movements. The first two movements are flashbacks, while the third is a distillation.

He points out a few insightful observations, such as that Karin’s mutilation is inverse of Agnes’ uterine cancer. The final scene recalls “bodily solace” that Anna gives Agnes in earlier scene, which is the central theme of the movie and the thesis of his essay.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Watership Down, 1978, Martin Rosen

Watership Down has so many thematic textures that I felt this was a good opportunity to mix things up. Rather than review the film based on quality (spoiler alert: I loved it), I have instead isolated a few major themes that I’ll flesh out in detail.

Keep in mind that this is not a children’s film, and even if the images resemble the hand-drawn animation of old Disney, the subject matter is far darker.

I will be spoiling the entirety of the film both in the text below and the screenshots. I would recommend that anyone reading this piece have already seen the film or at least read the book.

There are several themes that are pertinent to the film that I chose not to cover. One of the major ones is environmentalism and man’s impact on the plan. This message is crystal clear and hard to miss. There are others that I studied and decided to cut, such as Leadership (Hazel) and the sense of Community. These also are easy to pick up on. Instead I chose to focus on political oppression, the use of violence, spirituality and religion, and of course, mortality.

Politics and Oppression

“There is something oppressive in the air, like thunder,” Fiver says near the beginning of the film.

There are three major political groups in the film. The first Owsla is where the main characters originate. The Watership Down group is the protagonists and their quest for a homeland. The Efrafa is the group that they meet in the third act of the film.

It is clear early that while the protagonists are under the rule of the Owsla that they are oppressed. There is some sort of class or caste system that is not defined in detail, but it dictates access to materials (food, does, etc.). Only those in the upper echelon are privileged, whereas those in the lower class, like Fiver and Hazel, are oppressed. Another major character, Bigwig, is an officer for the Owsla, but he is sympathetic to those who are being subjugated. The form of government closely resembles fascism or any totalitarian rule where the leaders have unfettered control.

Oppression breeds dissension. Fiver has a psychic premonition that doom is upon them, and he and Hazel plead for audience with the chief. Bigwig facilitates their meeting and is later reprimanded for it. Fiver’s pleas fall on deaf ears, but he and Hazel are believers. After being rebuffed, they decide to flee the warren. When word gets around, others want to leave with them. The reasoning does not seem to be due to Fiver’s premonition. As we will see later, they don’t always believe him. The primary motivation for leaving is because they are being oppressed and lack basic freedoms.

When they try to leave, one officer tries to arrest all of them for “spreading dissension, inciting to mutiny.” This is again similar to fascism or totalitarian rule because those in power want to shut down any opposition. We know that Fiver’s vision is apolitical, but that is irrelevant to those in power. They require subjects in order to maintain their privileged status.

After they escape, the crew of Hazel, Fiver, Bigwig and others becomes a leftist and nearly communist role. They are interested in free living, community and collective harmony, which I will touch on in more detail later.

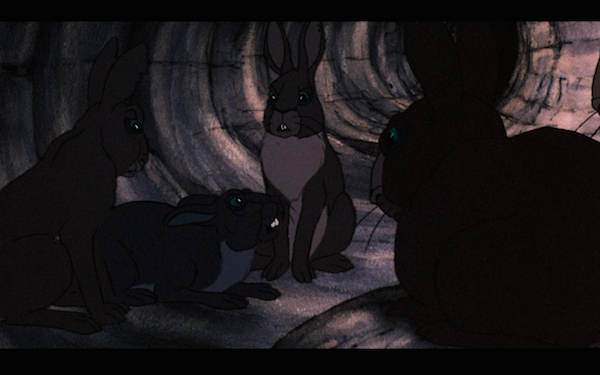

After they escape and reach Watership Down, they learn of the Owsla’s downfall from Captain Holly. Most importantly for the final act, through Captain Holly, we learn of the third group, the Efrafan. It is clear from Holly’s condition that this is not a pleasant bunch. They capture him, rough him up, and rip his ear in order to mark him. We then see inside their burrow. They look evil and menacing. Through this portrayal, it is clear that they are the antagonists that will threaten the harmony of Watership Down.

While doing some reading about this film, I’ve found some comparisons to Nazy Germany. Whether this is intended or not, there are several similarities. We first learn that they are overcrowded and cannot produce more litters. This reminds us of the tragic overcrowding of Jews in the ghettos and later the Holocaust. They mark their victims, just like they marked Captain Holly, and just like the Nazis marked the Jews.

Chief Woundwort is the leader and he is a beast. He is large of stature and for that reason he is not identical to Hitler, but he is unquestionably a dictator that rules with an iron fist. He sends out patrols that take stray rabbits to a council to mete out punishment, most of which is of a violent nature.

The Efrafans say that “everything out of the ordinary is to be reported.” Their methods are to annihilate opposition, and follow anyone under suspicion, as they do with Bigwig. Parallels could be made with virtually every totalitarian government, again including Nazi Germany, but also Stalin’s Russia, or any of the African, Asian or Arab despots.

When Hazel tries to negotiate terms with the Efrafa during their war, he suggests having independent, autonomous and free warrens. It is categorically rejected by the Efrafa. This proposal is close to communism, which of course is fundamentally opposed to fascism. Rather than negotiation, they rely on crushing, absolute destruction and refuse to stop or negotiate. In this manner, they are like Nazi Germany focused on total war to subjugate the opposition.

Violence

Violence is a major theme of Watership Down. The characters may be cute and cuddly rabbits, but they are ruthless and vicious. Even the “good guys” resort to violence in order to achieve their escape. In fact, the film’s violence begins with the Watership group threatening to kill a Captain of the Owsla if he stands in their way. That is the first fight scene, where Bigwig joins the group by standing up for the rebels, tethering himself to their cause and isolating himself from the Owsla in the process.

There are several instances of violence scattered throughout the film. There is the brutal sequence where the Owlans meet their end, or when the farmers shoot Hazel, and of course when Bigwig gets caught in a rabbit trap and nearly meets his end. The ultra-violence is near the end when they are at war with the Efrafans.

“You don’t know the Efrafans. They’ll never give up!”

The ending is war, total war — the same type of ferocity and bloodlust that drove World War Two to staggering levels of destruction. Even prior to the war, the Efrafa are bent on obliterating their opponents, as they prepare to murderously charge at the Watership group when cornered at river’s edge. If not for the crafty rescue, the Watership group would have likely all been killed.

As the Efrafans try to penetrate the burrows at Watership Down, they do so with a bloodlust. This is not about strategy, but about death. They want to destroy those who harmed them and, in their minds, stole their property.

The most violent scene is the fight to the death between Woundwort and Bigwig. At least it is intended to be a fight to the death, and neither side would have given up if not for other circumstances.

The freedom fighters use a secret weapon, a dog, in order to achieve victory. This could be seen as a deus ex machine plot device, or it could be seen as a weapon of mass destruction. An analogy could be made that the dog’s onslaught and end to the Efrafans is tantamount to the US dropping the atomic bomb in order to win the war. Both could be seen as atrocities depending on your perspective, but they both achieved the same result. They both saved lives for the winning side.

Spirituality/Religion

Spirituality, religion and even mythology play a central role in Watership Down. The introduction tells the creation story of how The Great Frith made the world and all the stars. The Prince of Rabbits had many friends that ate grass together. Just like the Hebrew creation story, the rabbit makes a hubristic misstep and loses his honored status. The rabbits (or Children of El-Haraira) are hunted by other creatures and have to meet the “Black Rabbit of Death.” As a way to offset against these grave threats, Frith gives his rabbits a white tail and makes them faster than any creature in the world.

Addition to the religious elements, there are also psychic phenomena that go unexplained. This is specifically the case with Fiver, who has a sort of precognition and foresight of things to come. He sees fields of blood that foresee the destruction of Owsla, the dangers inside the burrow of men, where Bigwig ends up snagged, and finally he senses the lurking evil of the Efrafa before they attack Watership Down. While he is not always believed, he turn out to be correct.

Fiver also has connections to the religious world. He can see the Black Rabbit, and during the memorable playing of Art Garfunkel’s “Bright Eyes,” he sees and perhaps participates in an adventure with the otherworldly being. Religion, mythology and the supernatural are all connected with death, as is the case with most human religions and a lot of supernatural phenomena. Christians believe in a Heaven, whereas mediums believe they can speak with the dead.

The rabbits are providential as opposed to secular. They refer to their religious world often, by saying “thank Frith,” “for Frith’s sake” or other phrases that humans would replace with the name of their God.

Their departure from Owsla is similar to the Hebrew’s Exodus from Egypt, and Hazel in many ways resembles a Moses type of savior character. He does not perform any miracles. Access to the supernatural is solely Fiver’s territory. Hazel, through his leadership, does encourage those who would otherwise be lower class, or even worse, slaves, to follow him to the Promised Land. He does call upon Frith once, offering his life for the safety of his people. Frith does not take this offer, responding “There is no bargain. What is must be.” With or without Frith’s intervention, Hazel (or Hazel-Ra as they call him when he becomes chief) leads his people to salvation.

When the film ends, they have achieved the harmony that Hazel, Fiver and the rest hoped for. They have reached their holy land. They are the chosen ones and are at peace in their version of paradise.

Mortality

“Whenever they catch you, they will kill you.”

Death is ubiquitous in Watership Down, beginning with the Creation and origin story at the very beginning, where the rabbit is warned to “be cunning and full of tricks, and your people will never be destroyed.”

The first actual death on screen happens during the departure from the Owsla before they reach Watership Down. Their way is full of obstacles, and they learn of the danger when a vulture swoops down and snatches a rabbit named Violet right in front of Fiver. In an instant she is living and free, and then the next, she is gone, facing imminent death.

Death rears its ugly head again when Bigwig is caught in a snare near the suspicious place with the “man smell.” Bigwig struggles as they try to figure out how to free him from the wire. He bleeds incessantly, and the process is slow for the rabbits to figure out how to remove him from the trap. He is slowly choking. After he is freed, he is close to death. He gags and the camera changes to his perspective, where his fading eyes look up and only sees the dark silhouettes of his companions. At this point, his friends and the audience assume he is dead. Fiver says, “Please don’t die. We got you out.” The group collectively utters, “My heart has joined The Thousand, for my friend has stopped running today.” They think he is dead, but in a refreshing moment, he comes to. This is one of the most disturbing scenes in the film. Not only is it the first time we see a graphic wound, but we fear we have lost a main character. This will not be the last time.

“We go by the way of the black rabbit. When he calls, we must go.”

The ending is foreshadowed with Fiver’s exposure to death during the “Bright Eyes” montage. This scene celebrates death, allows a major character to come to terms with it as an inevitable reality, and it prepares the audience for the final scene.

”Bright Eyes, How can you close and fail?

How can the light that burns so brightly, suddenly burn so pale? Bright Eyes.”

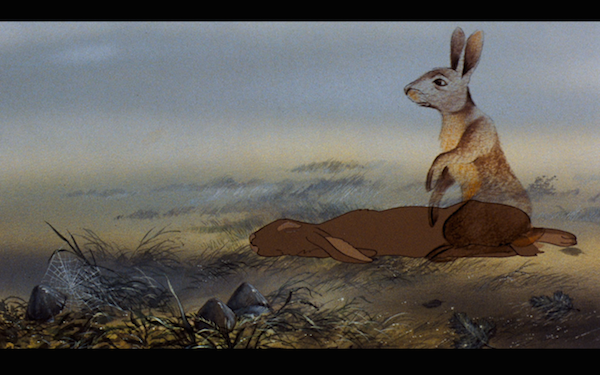

At the end, after years have passed and his people have long since settled, the Black Rabbit calls Hazel. His work on this earth has been done. He has delivered his people. His end is presented as a peaceful journey

The Black Rabbit says “I have come to ask if you would like to join my Owsla. We would love to have you. You’ve been feeling tired. If you’re ready, you can come now.” The Rabbit assures Hazel that his people will be fine. Hazel briefly hesitates and looks upon his people, at peace. They are fine and he has been tired. Hazel falls to the ground at that very moment, at first slumping and taking a couple of deep breaths before resting for good. The spirit leaves his body and he follows the Black Rabbit to a new Owsla.

The ending is a challenge. It is both somber and uplifting, and people react to it differently. We see death as tragic, but it is intended to be happy ending. Hazel’s life goals were achieved and he is ready to move on to the next phase, to join Frith. To me, the ending is extremely touching, affecting, and not manipulative. Death is a part of life, and a beautiful thing when a life has been fulfilled. Hopefully after death there is another promised land waiting. For Hazel, he has somewhere to go. He follows the Rabbit to what appears as the sun, and he joins his creator. However heartbreaking for many, it is a beautiful ending.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements

Passion Project: 2014 interview with Martin Rosen. He loved the book without thinking how difficult it would be. It was tough to get the rights. Richard Adams wanted nothing to do with the project simply because he was not a film lover.

The process was painstaking. All of the locations in the book were based on real locations that Adams knew. Rosen scouted these places and had them drawn as close as possible. He discusses at length the animation process, the voice casting and acting. He was fortunate to have a talented stable of actors, none of whom said no to the role, and they put their stamp on the performances.

The song is a key piece of the finished film. It was a financial requirement to have three songs in the film, yet Rosen was initially reluctant. “Bright Eyes” just fit with the theme.

A Movie Miracle: Guillermo Del Toro: People mistakenly think of animation as a genre and not a medium. Del Toro realized this from seeing this film. It created a world with socio-political and adult concerns. Watership Down is not an animation marvel, but people put the work in as best as they can while preserving narrative. It has a handmade feel that contributes to its quality.

Defining a Style: This is a series of interviews with a number of the animators that worked on the film. They all had positive experiences. They discuss the different styles they had an how they came together to form the final film. They also respect the film and how it broke ground.

Storyboards: The film can be watched with storyboards that appear in the upper right hand corner. This is partly a novelty, as it is difficult to seriously watch the movie with them on. However intrusive, they are interesting to see in small doses.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

Criterion: All That Jazz, 1979

ALL THAT JAZZ, BOB FOSSE, 1979

What separates All That Jazz from most musicals, is the level of honesty and authenticity. The musical numbers are all ways of expressing reality in an entertaining and artistic fashion, whether they are about the process and mechanics of putting together a Broadway music, or about one’s own mortality. Fosse’s mostly-autobiographical tale brings us into his world, the theatrical and directorial world, and uses that as a means to another world. More on that latter world in a moment.

The theater world is the one that Fosse knows the best, and he portrays it as a true insider. It begins with the cattle call, an arduous and brutal ordeal. The sequence goes on for a long time, nearly in a documentary style with clever editing to show the magnitude of performances that take place. George Benson’s version of “On Broadway” plays, reminding us what the stakes are. One of the dancers says he’s willing to change his given name (Autumn) if he gets the job. A job in a Gideon (or Fosse) production could make a career.

There are other theater sequences that are particularly effective. This was my third viewing, and one that struck me this time was the audition sequence with Victoria, who Joe had recently taken as a lover. Some may think that entitles her to special treatment, yet she gets none. She lacks in the talent department, so Joe pushes and pushes her away from mediocrity. You can see the pain on her face with every new attempt, and you sympathize when she thinks about quitting. This probably happens all the time in the theater world. She doesn’t quit and after a number of repetitions and being drenched in sweat, she gets the nod of modest acknowledgement. Gideon says that a take is better, and a sense of relief passes through her exhausted face. It was a nice character moment, performed well by the actress.

The other music pieces are part of Joe’s world. The adult-themed airplane number is performed as a dress rehearsal for the producers, but it takes a life of its own. It shows the director’s brilliance, but also his bravado. He’s not afraid to push the envelope, and the number is a reflection of how he lives – sex, drugs, and smoking. Another musical number is performed by his girlfriend and daughter, and is a great way of developing the character relationships in an entertaining and touching manner.

The other dance numbers were also part of Joe’s world, but not the same world. This world is just as open and honest, maybe more so, and they again show how Joe/Bob will go to depths that most filmmakers won’t.

Be warned, the remainder of this summary is going to be full of spoilers. This movie cannot really be discussed without referencing the ending.

Even though the dance numbers are entertaining and even fun, they are a contrast with the harsh reality of what Joe is facing. This is shown in graphic detail during the heart surgery, where they show the medical procedure happen – something I had never seen prior to this movie, and never expected to see.

That takes the movie to a different level. While in the hospital, Joe has a musical hallucination, which talks about how much he has done wrong, how he has failed. His decisions have led him to this point, with a fractured marriage, a stressful career, and literally, a breaking heart.

The final scene is pure brilliance. It is Joe saying goodbye to the world, including his professional peers, his family, even his enemies. The lyrics “Bye bye life. Bye bye bappiness. “ are dark, morbid, yet they are celebrational. “I think I’m going to die. Bye bye my life, goodbye.” Even though the movie clearly is leading up to the finality of Joe’s life, the harsh, abrupt ending is still shocking. It is still bold. It is still amazing. Even though the prior ten minutes were full of smiles and festivity, the stark reality is that you will be zipped up into a body bag.

Phenomenal movie. I’ve long called it my favorite musical ever, and that was cemented with yet another viewing.

Film Rating: 9.5/10

Supplements:

There are a ton of supplements, so I’ll give an abbreviated survey here.

Commentaries: There is one full commentary with Alan Heim, the editor, and Roy Scheider, the lead actor. Even with the shorter duration, Scheider’s is the more interesting, as is to be expected. Heim’s is good too, but there is already a featurette about the editing on the disc that is more effective. One thing that’s surprising from both commentaries is about Fosse’s take on the autobiographical details. It seems that he minimized the fact that it was based on his own experiences, yet they were undeniably him. Heim points out that the address on the medications was Fosse’s address, and he would refer to the lead character as “you” when addressing Fosse, which the director didn’t like.

Ann Reinking and Erzsebet Foldi: The actresses that played the girlfriend and daughter have a good rapport as they reminisce about their experience. The young actress had no idea of the scale of the movie when she was doing it, and it was something hearing her talk about seeing people lined up around the block.

TV Appearances: There are three of these; one with Fosse and Agnes de Mille, and the other two with Fosse solo. It’s weird seeing Gene Shalit doing an interview. I’m not a fan, but Fosse makes for an interesting subject.

Featurettes: There are several. My favorite was on the editing, which sort of negated Heim’s commentary. There were others about the music, on-set footage, and even one on the making of George Benson’s “On Broadway.”

Documentary: This is short by Criterion standards, but long considering everything else on the disc. It is roughly thirty minutes and has several interviews with people involved with the production, including Sandahl Bergman, who was flown in just three days before her scene and had to learn a complicated dance routine.

Between the quality of the movie, restoration, and the extensive features, this is so far the best Criterion release of the year.

Criterion Rating: 10/10