Blog Archives

Bigger than Life, Nicholas Ray, 1956

Nicholas Ray had an uncanny ability at capturing the social isolation and detachment of certain groups during the 1950s, that contrasted with the pristine, manufactured image of the obedient nuclear family as seen on TV. He played around in a variety of genres, such as the western (Johnny Guitar), the teenpic (Rebel Without a Cause) and family drama with Bigger than Life. Even if the setting and plot are different, the primary message is the same — moral decay and hypocrisy that is taking place with the changing times.

The first shot is fired by showing Ed Avery’s (James Mason) poor financial condition. He is a well-spoken, intelligent school teacher, yet he is required to moonlight as a cab dispatcher in order to supplement his income. Embarrassed, he lies to his wife, saying that he has to stay late in order to meet members of the school board. At one point of the film, he decries that “I’m a school teacher, not a plumber,” when someone asks him about money. By making a direct comparison between a learned educator and a tradesman, Ray is making a commentary on the inadequate income of teachers, a disparity that sadly still exists today.

When we meet his family, we are surprised to see that he lives in a traditional, suburban neighborhood, reminiscent of the types seen on TV shows like Leave it to Beaver (coincidence: Jerry Mathers who later played the Beaver appears in this film). This type of living would be considered middle class in the 1950s. He has a wife that stays at home and a child that enjoys watching television, just like most other suburban families. He has to work both jobs in order to maintain this status of living. We can tell from the paintings and posters in the house that his true passion is not at home, but instead exploring the great tourist cities of the world. Circumstances will not allow him that luxury.

It is sickness that changes him. He has a rare condition that inflames his arteries, with a dire prognosis of one year to live without trying an experimental drug – cortisone. It is unfortunate that they named the drug, which back then probably was more in the experimental category, but today is commonplace for treating a variety of injuries and has documented side effects. What happens in the movie is not what would happen in reality with this medicine, but that is beside the point. He is really sick of modern, American society, and the side effects that materialize motivate him to reject and criticize his world.

The medicine works at first. In fact, he is happier than ever at home and he participates and seems to belong in the stereotypical nuclear family environment.

The new Ed embraces materialism and consumption. In order to please his wife, he takes her to an expensive dress shop and encourages her to pick one out that she likes. They cannot afford such a dress, and this expense will come back to haunt them later in the film. What is important is that, or specifically he, feels the need to purchase a dress because that will make his wife happy and give him the appearance of being a good husband. They do not need the dress, just like they do not need most material objects found in their home, but they are helpless not to participate in the capitalistic craze.

It is about midway through the film when the change in Ed begins. His wife abruptly acts out by breaking the bathroom glass mirror in a sudden rage. “You’re not in the hospital now!” she yells. He looks at his reflection in mirror and sees himself in shambles. This action is unprovoked and his wife quickly apologizes, but it sets his downfall in motion. Is the mirror fragments in two, so does his personality. What emerges is an unpleasant, unkind human being who thinks he has all of the answers for society’s ills.

One of the better scenes of the movie is when Ed is at an evening parent-teacher conference. This is the new Ed, and he says what he really thinks without a care of how it is received. He compares his students to gorillas that are victims of the deterioration of poor educational values. The fact that teachers are paid so poorly probably sparks this manner of thinking. Without economic incentive, why should they bother shaping and molding their students into bright and productive members of society? When he says that they are teaching an inferior class of students, one person suggests that he should be the Principal. In reality he is saying what the other teachers will not say, that things are not quite right.

This new Ed has a new world vision and challenges himself to make a difference. Meanwhile, his home life falls apart because he expects too much of his wife and child. He becomes a bad husband and a bad father, and things get worse as he becomes addicted to the medicine that is supposedly healing him. He takes more than his prescribed dosage, even forging prescriptions, and eventually loses his mind. The latter portion of the movie is Ed settling into his psychosis and nearly committing a terrible act.

The movie ends by him coming to after being off the medicine. He remembers his behavior and immediately feels ashamed. You could call it a happy ending, and for the Avery household, it probably is for the short-term. In the long-term, there is no way that life will be happy and pleasant for them. These issues still linger and will not resolve anytime soon. If Ed gets sick again, the cycle could repeat itself or he may die. In a way, this ending is an embracement of the status quo. There are no quick solutions for the Avery family, just as there are not for suburban society at large.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements:

Commentary: with Geoff Andrew, film scholar and author of The Films of Nicholas Ray. This was a disappointing commentary. I’m sure Dr. Andrew has plenty of credibility as an academic, but I think he left a lot to be desired. His voice is dry and not exactly exciting, although that’s not exactly uncommon in academia. Many excellent commentaries come from scholars with dry and monotone voices. It is the material that makes the difference. Maybe it was the level of preparation, but Dr. Andrew did not provide as much insight into the film as most Criterion commentaries. He makes many interesting comments, but does not elaborate on them with much detail. For instance, he mentions that Ray thought teachers were underpaid, and then moves onto another point, often making an observation that the viewer can make.

One of the more interesting insights was that Ray had interest in architecture, specifically Frank Lloyd Wright. This can be seen in a great many of his films, and especially Rebel Without a Cause. Ray used buildings very well in his films, and this was no different. Andrew makes some observations about the posters in the house. Downstairs has the public type of décor, like the Grand Canyon. Upstairs is private and exotic, with posters of faraway, cultured cities.

This period of Ray’s life was a period of depression and many of his themes were formed by the red scare, HUAC politics of the time.

Profile of Nicholas Ray: This was a 1977 TV interview with the late critic, Cliff Jahr. Not too much of the interview was about Bigger than Life. This may be the only Ray film to come to Criterion, so this can certainly be excused. One of the first questions is whether Ray gets tired of questions about Rebel Without a Cause. The answer was an emphatic no, because the subject is still relevant today and people connect. He only likes to talk about films that remain relevant. Most of the follow-up questions have to do with Rebel, including the obligatory James Dean question. I’d wager he was tired of those.

He talks on a few occasions about his mentality back during his peak filmmaking years. He says that a lot of his working back then was insanity and that “I work better now. I like myself better now.”

Jonathan Lethem: This is one of the novelists favorite films and he does a great job with his analysis.

What’s interesting about the movie is what it excludes. There is no teenage rebellion, rock and roll, or any deviancy. Things are too perfect. I thought the same thing when I saw how well behaved the students were in class. This was definitely deliberate.

There are numerous class issues. The house may look very suburban, but it has several blemishes. With a closer look, Lethem says it “barely qualifies” as a representation of suburban life. The fiction is that they can afford what they want, which is of course not the case. That’s why the dress scene is so important.

Susan Ray: Ray’s ex-wife reflects on her husband.

His process was “creative chaos” and “responsiveness.” He was keenly aware of what was going on around him, and he was best at observing people’s natures. He “had passion in finding deepest possible truth in a human being.”

A real hero is a “poor slob” like you and me, as he would put it. Even though he had a sense of masculine bravado, he also had a humble and sensitive side.

Ray’s choice of suburban life was because he saw the deadening and sterility. He had a jaundiced view of his own generation, calling them “betrayers.”

Criterion Rating: 8.5

Three from Jean Vigo

À PROPOS DE NICE, 1930

Jean Vigo’s debut film falls very much into his idea of “social cinema.” He was a leftist (specifically an anarchist with communistic leanings), which I’ll talk about in more detail later. He was driven to film as a means of expressing his political world view.

À Propos de Nice is a silent documentary short, but it is unlike most of the ones you’ve likely seen. There are no title cards and little actual narrative. It is more of a slice of life documentary about the coastal town of Nice, France. It shows the flow of rich vacationers contrasted with the locals that put on a show for them, and reaches a crescendo that makes a thinly veiled political statement.

The beginning shows a number of upper class, upper crust people lazily enjoying the sun-drenched city. Some are simply walking and looking distinguished; others are enjoying a book on a beach chair; while others are taking sun naps. Occasionally Vigo will show a lower class citizen just to keep the viewer’s attention. For instance, between shots of opulence in action, there is a shot with a garbage collector. There is another shot with a clearly wealthy individual sitting in a chair, and a homeless person sits next to him. Vigo holds that shot, accentuating their differences, yet they are still both sitting idly near a gorgeous beach.

Vigo gets a little more adventurous with some daring, staged shots, which get crazier as the film goes on. There is one such scene with a lady sitting quietly in a chair. The scene cuts and we see the same lady in the same position, with a different wardrobe. It cuts again to yet another wardrobe, and continues to cut a couple more times. The last cut reveals her sitting completely nude in the same chair position. In this manner, the documentary is both jarring and humorous, which would be a constant.

Shots become more abstract as Vigo shows buildings from unusual camera angles, often sideways. He shows poor men wearing big hats, and we discover they are serving pies to their rich visitors. Finally we are shown a parade, including some large, comical figurine faces that were also shown out-of-context in the very beginning of the film. This is the real city of Nice. These are the workers that entertain the rich tourists, that depend on their livelihood and choose to look silly in order to facilitate the pleasure of the class above them.

The film ends with militarism and radical dancing. We see ladies doing the cancan, raising their legs higher in the air with each kick, threatening to reveal their hidden mysteries. These are again lower class, possibly prostitutes or at the very least loose women. Unlike the idle rich vacationers, they are partying wildly without a care in the world. They even dance over a pothole, with the camera covertly positioned inside, shooting them from below in a voyeuristic manner, even though it is obviously a staged shot.

We end with workers, soldiers, and fire. The message is clear when analyzed closely. It is at the hands of the workers that the future lies. Vigo shows them up to the task, upbeat and engaged, but the ending is not resolved.

Film Rating: 8.5/10

TARIS, 1931

Taris stands apart from the remainder of Vigo’s work. It was a commission to profile the famous French swimming champion, Jean Taris. While it was not a vehicle for his “social cinema,” it gave him the opportunity for some technical experimentation and expression that would be used again in his two final films.

The 9-minute short is a vanity film, with Taris showing off with his diving ability and his mastery of various swimming strokes. Vigo’s film language helps portray the swimmer in the most positive light possible. He shows close-ups of him while he is working hard, the respected yet agonized face of an endurance athlete. He reverses some of the diving scenes to make it appear that he dives, and then floats back to the diving platform.

The best footage is when Taris is underwater. There is no sound, which is appropriate for underwater footage. Taris is alone in his element. We see him in close-up, holding his breath, yet still enjoying himself and preening for the camera. If there’s any doubt as to his stature, it is quashed when the diving scene and a trick dissolve makes him appear that he is walking on water. Some may have seen that sacrilege, whereas his fans probably found it appropriate. He was an athletic celebrity.

Even though this is a technically accomplished film, it exists for the sole purpose of making someone look good. That makes it the outlier of the four films that Vigo would complete in his lifetime.

Film Rating: 5/10

ZÉRO DE CONDUITE, 1933

Zéro de conduite – or Zero for Conduct, as I will refer to it – is the most fully revealed of Vigo’s “social cinema.” I mentioned above that he was an anarchist. Even though his politics were complicated, Zero for Conduct helps clear them up. In some respects it is a blueprint for exactly the type of anarchic revolution that Vigo longed for, yet it takes place in the unlikely setting of a young boy’s school.

The children in the boy’s home are characters that many can relate to. They push the boundaries of authority, and try to get away with whatever they can. They are into hijinx, practical jokes, and overall misbehavior. They are not a peaceful bunch, and they give it to their teachers at every opportunity, whether to their face or behind their backs. The only exception is Monsieur Huguet, who they find as an allay and a character that understands them.

The other teachers are impatient for any mischievousness, and they rule with an iron fist. “Zero for Conduct” is the punishment for any transgression. It means that they are not given their freedom on Sundays to visit family or friends, and instead are required to stay in school at detention. Furthermore, the teachers dole out the punishment arbitrarily and unfairly. Vigo is intending to portray this as a totalitarian state where the lower class’ (or children’s) rights are being impeded.

The children may be the goats, but they also get to be the heroes. With some assistance from the friendly teacher, they lay out plans for rebellion. The planning is carefully orchestrated and is not put into action until the authority tries to compromise one of the oppressed. It begins with an expletive, continues with a rowdy food fight, and the revolt is in progress. The children hoist their flag and march with exaltation. The sense of freedom and liberation is palpable, just as Vigo expects that it would be in reality. Even though the film is of revolution, it is combined with the exuberance of childhood merrymaking.

Zero for Conduct was banned for a number of reasons. First and foremost, there is clear male nudity during the march scene. There is also the acknowledgement of a homosexual relationship between two males, one of which looks effeminate to easily be confused as a girl (full disclosure: I thought he was a she during the first viewing). Not only is it apparent on screen, but even the school officials take notice. In one scene when the pair are walking arm in arm, the headmaster tells another teacher that “we need to keep an eye on these two.” This was 1933, where the subject of homosexuality was barely even believed in common society, much less presented in the media arts. Finally, there was religious consecration as the children place one teacher in a crucifixion pose during the rebellion. This was too much for the censors.

While Zero for Conduct is an understandably controversial film that was a product of the post-Bolshevik era and Vigo’s politics, it is also far ahead of it’s time in film language. During the early years of French Poetic Realism, there had been plenty of radical images, but none that came close to Vigo’s penultimate film.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements:

Since this entry is about only three short films from The Complete Jean Vigo disc, I am only going to cover the commentaries in this post. There will be another post about L’Atalante and a wrap-up post to come, which will cover more supplements.

Commentaries – Michael Temple, author of French Film Directors: Jean Vigo contributed commentaries for all four of Vigo’s films.

All four films were producted with Boris Kaufman, brother of the filmmakers that created the legendary Man With a Movie Camera, and he had significant success after the Vigo years. He already had a great deal of film background when the collaboration began, whereas Vigo was young and inexperienced. The partnership may not have happened if Vigo had not financed À Propos de Nice with his marriage dowry. The collaboration was beneficial to both, and they grew as filmmakers, which is more than evident from the quality of their work.

Temple claims that Vigo is considered one of the more celebrated filmmakers in French film history. This is amazing given that he made a mere four films, and only one of which was a full length feature. Vigo’s work was not appreciated during his lifetime and would be rediscovered by filmmakers such as Truffaut and Godard during the French New Wave.

I’ve already referred to the term “social cinema,” which is a phrase I received another source (Republic of Images, Alan Williams.) Temple says that Vigo called À Propos de Nice a “social documentary.” It is divided into three parts: 1) Wealth. 2) Contrasts 3) Revolution. Vigo himself appeared in the cancan dance sequence, kicking his legs up with glee with both women around his arms.

Taris was the exact opposite of Apropos because it was commission. Vigo received it because of his name recognition after À Propos de Nice. He used the commission to learn more about film technique, which he would use in his two final films. The most notable items he recycled were the underwater scenes, which he shot by using portholes underneath.

The producers did not like his version and hired someone else to finish. We do not know for certain whether it is all Vigo’s work in the final film. Vigo rejected the film, but said he like underwater scenes.

Zero for Conduct was Vigo’s signature film. It was both based on his personal experience in a children’s home, and it expressed his anarchist ideology throughout the film.

Merde is a magical word in anarchist culture. It is a difficult translation from French (literally translates as “shit”), but the word is not always profane. Sometimes it is just a desire to shock or go against conventions. It is a word used within revolt.

Vigo sees anarchism and revolution as joyful, and that is eloquently presented in the film. The kids are having an absolute blast, while it is also a call to freedom.

The final confetti slow motion rebellion scene is one that Vigo borrowed from his underwater scene. If you watch it carefully, it is reminiscent of how Taris was shot with it’s subject swimming under the water.

Don’t Look Now, Nicolas Roeg, 1973

I remember hearing about Don’t Look Now when I was a youngster. I probably even saw it, although it was at such a young age and was competing with a lot of schlocky horrors and thrillers, that I undoubtedly forgot it. Even though it was and is a highly regarded thriller, it was probably not my cup of tea. Now, many years later, it is interesting to revisit it as an art film and a thriller. It works effectively as both.

This film also deserves the requisite warning about spoilers. It cannot be discussed without mentioning pivotal scenes in the beginning and end. If you haven’t seen it, please do not read this review. It is an ending that has to be experienced without foreknowledge. It is also an ending that enhances further viewings and analysis.

Don’t Look Now could be seen as a story told backwards from the ending, as there is symbolism about what’s to come littered throughout the mise-en-scene. It could also be seen as a film with appropriate bookends. It begins and ends with a tragedy involving some (or all?) of the same characters. While there is plenty of room for exploration, what’s unquestionable is that this was crafted in a way that recalls the beginning and projects the future. Virtually every scene has some reference to either, and most nod to both.

As for the symbolism, the most obvious is water. The majority of the movie takes place barely above water, from the tragedy in the beginning to the wanderings around Venice. They constantly tie water to death and, by extension, to the daughter. As he floats the canals, John sees murder victims extracted from the water. In one scene he notices a peach-colored, naked baby doll in the water, which is one of the most overt references to his daughter. Through John’s eyes especially, he is constantly searching the water for some meaning, whether it has to do with his daughter, his wife Laura when he believes she has not left, or even for his own spirituality.

The idea of belief is another major theme. John would not choose to visit Venice after the drowning of his daughter, but his profession as an architect brings him there. More specifically, a church brings him there. Does God lure him there? We can tell by his mannerisms and statements that he does not believe in a God. He actually feels some hostility towards the hypocrisy he sees within the church. Conversely, his wife takes on a more uncommon belief while she is in Venice, which is that of the paranormal. She believes that a blind lady could see her daughter Christine in between them at a restaurant. John tells her that “seeing is believing” and that he believes her, but he may be lying in the same way that he lies to his clerical associates. Because he does not believe in God and doubtfully believes in the paranormal, his lack of belief contrasts with the devout belief of the others in the film. Maybe God lured him to Venice, or maybe a paranormal intuition of his daughter lured him. Whatever power is at hand, he is naïve and dismissive of it.

There is also the matter of acceptance and overcoming the grieving process. The Baxters are wallowing in their misery when they are in Venice. Whether the premonition is true or not, the reason that Laura embraces the psychics is because she needs some sort of resolution. The blind psychic tells her that she has seen her daughter, who was sitting between them and laughing. “You don’t have to be sad,” she tells Laura. She clings to the psychics because of this assertion of comfort and resolution. She yearns to understand what happened with her daughter, and wants to believe Christine is happy and that their agony is misplaced. Again, this contrasts with religion, because the entire concept of Heaven is what the psychics claim to have seen in Christine – a happy and comfortable place. Once she has embraced belief of the psychics, she seems to accept the death of her daughter. She even interacts between the psychic and religious worlds by lighting candles in the church for Christine, which is out of happiness. What is ironic is that emotion is borne out of something far from the church, yet it is expressed within the church.

Regardless of how he acts around his wife and the clergy, John does not get relief from either psychic phenomena or religion. He instead is a practical man. Again, he believes in what he sees, and he is constantly looking for something in Venice even if he won’t admit what. He exclaims at one point that “Christine is dead!” and then repeats the word “dead” several times for good measure, as if he is trying to force himself and his wife to accept. He is not convinced, otherwise he would not have followed the red raincoat at the end of the film, the same one that results in his undoing. His belief that “seeing is believing” ends him. He was mistaken when he saw the red raincoat and chased after it, just like he was mistaken when he thought he saw Christine in Venice after her departure. The ladies think he has second sight, but it is his first sight and reliance on observation that deceives him.

What about the love scene? It is quite a brilliant bit of filmmaking despite all of the controversy and rumors about it. Many have argued that the scene is unnecessary, but I think it is a key component of the movie and expertly done. First off, the scene is a “love scene” and not a “sex scene.” They may be engaging in the act of intercourse, but they are expressing the love between them. In some ways this is a way of them taking solace in each other, and in another way it is another example of the relaxation after Laura believes that Christine is happy. The quick cuts between the actual sex, dressing and undressing make it less provocative, but they also show that it is a momentary reprieve. We are reminded during this lovely moment that it will end, and that they will have to go on about their lives. The scene also reinforces that they are unquestionably in love with each other, and it is a combination of the love for each other and that of their daughter that prompts this obsession. In Venice, they are looking for comfort with and for each other. The love scene is the only time where they truly accomplish it together.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements

Don’t Look Now, Looking Back: 2002 documentary by Blue Underground. Director Roeg and Director of Photography Anthony Richmond talk about reoccurring images that are not understood until the end. Using the color red and broken glass were not coincidences. They were deliberate. They share some stories from the set, such as when out-of-character Sutherland says “I don’t like this church” to Christie. They overheard and liked the line so much that they scrapped the script and used the real conversation.

They talk about the love scene in depth. They knew it would be controversial, which is why the decided not to cut it in a linear fashion. To film the scene, they took a small crew to a hotel and the entire shooting took place in an hour and a half.

Death in Venice: 2006 interview with composer Pino Donaggio discussing the music he created for the film. This was his first film. He didn’t initially understand why they called him for an important movie. Roeg gave him a trial to come up with a couple of themes, which worked. They were excited about the music. Producers liked it as well and decided to give him a shot. It was a lucky break as it began his career scoring films.

He talks about his decisions during crucial scenes. The soft piano playing at the beginning is deliberately not played perfectly, as if a learning child could have played it. He wanted an orchestral tune for the love scene, but he admits now that came from his own pride. He changed his mind after watching the scene.

He intentionally did not use typical horror type of music, which I think really enhances the film. He used single instruments like the flute because that expressed pathos and fear. That flute sound has been imitated in other movies.

Something Interesting: These were some assembled recent interviews with co-writer Allen Scott, DP Richmond, Sutherland and Christie. It was the best of the supplements in my opinion, mostly because it was a recent wide ranging discussion.

Roeg was not the first director attached, but he was the most thorough. Introduced the theme of “nothing is as it seems.” They had to change the short story, which had a couple with a dead child, but the actual death scene is not in the Du Maurier story. The story did not give John the motivation to be in Venice, whereas the movie added his profession as an architect.

There are more good stories from the set, like how Richmond was in the cold water for six hours in order to capture the scene where John finds his drowned child. Sutherland wasn’t going to do the church falling sequences, and then stunt man refused to do it. Sutherland decided to do it after all and he got more than he bargained for. They left him hung up there suspending and even pushed him into the shot.

In the script, the love scene was only described as: “They make love.” They had a camera, a couple lights, and went in with skeleton crew and shot it. Nobody saw the negative. The AD says they did it so well that people thought it was real. They address the unsimulated sex rumors and refute them absolutely. Donald talked about how un-sexual the mood was during that scene. They had short actions and cuts, with loud noises in between. Christie says that filming sex has changed since then. Now they display sexual skill, whereas with Don’t Look Now it went from shot to shot, and she says even though it was not real, it was directed like it was real making love.

Nicolas Roeg: The Enigma of Film: Danny Boyle and Steven Soderbergh discuss Roeg and how he influenced them. Boyle says you can spot a Roeg film in seconds. He used to think it was the zoom lenses, but it is not that now. They both say that the lack of writing his own work doesn’t bring him down. “He writes with the camera” – Soderbergh. They both acknowledge that Roeg was good at handling time, whether in a non-linear fashion or compressed. They both talk about how they were inspired by him to the level that they stole scenes from him. Soderbergh gives an example with Out of Sight, where they inter-cut the making love with getting dressed.

Graeme Clifford and Bobbie O’Steele: Film historian O’Steele talks to editor Clifford. Julie Christie actually got him the job after they worked on McCabe and Mrs. Miller. Roeg wanted subtlety and visually connective, so things could be pieced together later. A lot of it is about process, and they began after the shoot had finished and the director had rested. Having seen and loved Walkabout, he was confident of what Roeg would like.

Nicolas Roeg at Café Lumiére: This was a Q&A after a screening in London. Roeg has a slow and sincere cadence that makes him not the best interview subject although what he talks about his fascinating. He thinks that film writing is unlike any other writing, much closer to literary. He doesn’t like rehearsing because you miss “chance and chaos.” Studios and producers hated this strategy because they wanted their safety nets, wanted to evaluate talent. He says that everyone involved is “all nervous” because nobody knows if the film will work out.

He talks about how independent film is tough now. There were more independent producers back when he was in his heyday, but it was still not easy. He speaks in praise of Harvey Weinstein, despite his hostile reputation, and how he gave Tarantino a lot of room to work. Roeg has trouble reading screenplays that he is not working on because “they are rarely beautifully written.”

They were screening it for DuMaurier, but they would not allow Roeg to come because he had changed so much. Later he got a letter from her. She told him that his film reminded her of the couple she saw in Venice that prompted her to write the story. It was a pleasing letter.

He talks about how the BBC had the love scene cut out. People were outraged and demanded that it be put it back in.. The BBC put it back in, and most agree that the movie falls apart without it.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

A Day in the Country, Renoir, 1936

Even if Renoir’s A Day in the Country is barely over 40-minutes long, was unfinished and lost for 10 years before being edited for release, it is still one of the quintessential representations of 1930s French Poetic Realism. The setting out in the country and the focus on being in nature and how the characters react to their surroundings is the poetic element. This is particularly revealed through the eyes of Henri and Henriette, both hopeless romantics who are looking for something poetic to distract them. The realistic element is the way that the plot unfolds. Rather than give away the ending in this post, because I implore people to watch this accessible Renoir, I’ll just say that realism means things don’t always work out the way people want or hope for.

A Day in the Country is a joyous movie, although two different versions of joy are juxtaposed against one another. A Parisian family wants to escape from the stuffy Paris, get some oxygen, and enjoy the luscious and beautiful French countryside. The joy for Henri and Rudolphe, two scheming locals, is having a group of Parisians to take advantage, specifically the young women. They are enthralled as the youngest, Henrietta, swings gracefully on a swing.

Given the short film length, not much time is spent on character exposition, but aside from a few details, it isn’t necessary. The characters of Rudolphe and Henri are explored as they sit in the café. Rudolphe considers himself a player, and ridicules Henri for being a serious man that wants a serious relationship. “Whores bore me, society girls are even worse,” Henri says. He is a serious romantic. You can tell this not only from the words he says, but his demeanor as he says them. Romance is not a joyous topic for him, as he has yet to find someone who shares his ideals.

Much of the film’s comedy is related to the double meaning of catching fish. The patriarch, Monsieur Dufour and his future son-in-law Anatole are obsessed with bringing a fish back to Paris to fry. Meanwhile, Rudolphe and Henri hatch a plan to lure the two women away from their family for their own amusement. After the two men talk in the café about their plans to catch the ladies, the scene cuts to the other men talking about fish. These two conversations can be contrasted, even if they are on completely different subjects. Monsieur Dufour is explaining to Anatole, who isn’t the brightest bulb, about the nuances of the fish they plan to catch, specifically the difference between the chub and the pike. Anatole is lost when it comes to fishing, whereas Henri is lost with love. Rudolph and Monsieur Dufour are the self-proclaimed experts.

When the two women talk, it is a variation of the men’s conversation, only the subject isn’t about catching fish, men, or women. The younger Henriette reveals herself as a romantic and has a love of nature. She is enraptured by her surroundings, and enjoys herself, whether she is on a swing, a skiff, or just lying on the grass. As they explore the potential for riding in a boat, she leaves her hat to save their picnic spot. This gives the men their ‘bait.’ It works and the entire family warms to the two men instantly, setting their plans in motion.

The men get the attention of the women and find some common ground. They get along splendidly. Madame Dufour is outgoing, giggly, and easily plays into the charms of the men. Henriette is still an introvert, but she is excitable about having a good time in nature, especially if she has the opportunity to ride in a boat. To lure the men to agree to let go of their women, they bring fishing poles. The Dufours consider them kind gentlemen, and naively let them do as they please with their women.

Rudolphe was hoping for Henrietta, and had arranged as much with his buddy, but then Henri manipulates the situation and gets her into his skiff. He sees something in Henriette that he sees in himself, and he is not going to let his mischievous friend take advantage.

The character contrasts are distinct, but they make the film even more enjoyable down the stretch. Rudolphe and Madame Dufour are both outgoing, playful, and they have fun with the adventure of the chase. Henri and Henriette are also similar. They are demure and romantics. Henriette is swept up in excitement as they row along the Seine. Henri has his mind on something different altogether, and when she begins to figure this out, she is reticent to continue. If not for crossing paths with their counterparts, who are loudly and boisterously having a great time, things might not progress. They do, however, and if not for a chirping bird, they may not have gone further.

The last few minutes are abbreviated because the film wasn’t finished. They work as a conclusion to this short film, but if Renoir’s vision of three connected short films had come to fruition, this could have been among his masterpieces. Even at the abbreviated length, I consider this to be one of his strongest works, and the story behind the story is almost as captivating as the film itself.

This was a pivotal period in Renoir’s career. He had already become an established star director, and he had become more comfortable in his craft. In A Day in the Country , you can see him exploring techniques that would result in his finest films, like La Grande Illusion, La Bete Humaine, and Rules of the Game. He plays with deep focus photography for many scenes, such as when the men are talking in the café and a swinging Henriette is framed by the window. This technique would be mastered in later films, most notably Rules of the Game. He had become deft at exploring character contrasts, which he did so terrifically in La Grande Illusion.

A Day in the Country stands on its own as one of Renoir’s greatest achievements, but it is also evidence of a master that was progressing in his craft.

Film Rating: 9.5/10

Supplements:

Renior Introduction: The initial idea was to shoot a 40-minute short film with the production value and acting talent as a feature. He wanted to shoot three shorts of that length, which in sum would become a feature. This sort of omnibus feature had not been done by then, but has since.

In a weird digression, Renoir argues for plagiarism. I don’t think he means it the way we understand the term. He means using stories as templates to embellish into a different story, and that has and is regularly done today. I can only speculate that back then, people thought it took nerve to alter a story by someone as heralded as de Maupassant.

The Road to A Day in the Country: This is a piece from Jean Renoir scholar Christopher Faulkner.

1935 he was very active with the popular front, militantly active. While he was leading the popular front and making films (like The Lower Depths) in the language of the movement, he made this one that seemed out of time politically.

Part of this was his coming to terms with his father, the famous painter, whose legacy likely continued to overshadow Renoir’s directorial career. Faulkner thinks this is a resolution with the past that he would return to frequently. The area that they filmed was an area that impressionist painters had worked in the 1880s. Many shots were homages to impressionist paintings.

Rain interfered and slowed down production. It took seven weeks, only 22 days of which were dedicated to shooting. Faulkner disagrees with Renoir’s assertion that they changed script due to rain. There was evidence that they had written in rain. Nevertheless, the rain did shut down production and cost money. Jacques Becker shot some material later when Renoir was not available. 23 shots in the completed film were shot by Becker, but according to Renoir’s instructions.

Producer Pierre Braunberger was Jewish and had to leave the country when war broke out, and had to take all his belongings including the film. He edited it in his mind during his exile, but it could not be seen until 10 years later when the war ended.

Marinette Cadix and Marguerite Renoir later edited the film into what we see today.

By the time of the release, Renoir was in the USA and basically forgot the movie. He had nothing to do with the final editing of the film.

Pierre Braunberger on Jean Renoir: They had worked on a great number of Jean’s early works. He speaks reverentially of Renoir. He made A Day in the Country for Sylvia Battaille, who he was in love with.

He talks about the rain and production problems. Both Renoir and Battaille got sick of it, and they shut down the film. They had hoped to finish the film, but the war and exile changed those plans. When he was hiding on an island, he had a lot of time to think. In his solitude, he realized that he could finish the film with two titles cards. Voila.

Un Tournage a la Campagne: This is a long series (1:29) of scenes and outtakes from the production. Some of them add scenes or extend scenes included in the movie, but the majority are in sequence of what we see in the finished film. They show some of the filmmaking process, with the setting of the scene, calling action, and other background set details. They even show mistakes by the actors and/or crew. There are some sequences that are significantly longer, such as the swinging scene. What’s interesting is they had a lot more footage to make a longer film. Some of the footage is of poor quality. Some even has no sound, probably because it was going to be added in later.

One thing that is impressive about all of these outtakes is the skill of the actors. We can see take after take of them giving their all. I was mostly impressed by Battaille, who on a moment’s notice could turn on the childlike giddiness or enraptured romanticism.

Renoir appears prominently in these outtakes. You can always hear his voice in the background and he is encouraging. Even though I enjoyed the entire series (although many might find it long), I especially liked the tribute to Renoir in the end credits where they show outtakes of people saying “Here is the boss.”

Renoir at Work: Christopher Faulkner examines the outtakes of the film. This is the only set of outtakes for any Renoir film, so they are important to see how he worked.

We see how Renoir interacts with the actors, and starts the scene by using the first line of dialog and he praises the shot. This is how he became “an actor’s director.”

Some of the later scenes are after Renoir had left for The Lower Depths and Becker had taken over. We can tell that Becker followed Renoir’s instructions.

Screen Tests: These are a series of screen tests with all (or most) of the actors. The initial scenes of Henri and Henriette are mere impressions, as they quietly react to each other.

The mother, father, future son-in-law, grandmother (man in women’s clothing) are just looking at the camera and around. Even Renoir gets a screen test.

Some have expressed reservation about Criterion publishing what is essentially a film short, but there is so much extra material here that isn’t characteristic of classic film. We get spoiled by releases of recent films, such as the Wes Anderson collection, all of which have a ton of supplements. A Day in the Country has nearly the same volume of supplemental material, which is a rarity for a classic French film.

Even though this is an early release, it has such great supplements and import that it is an early contender for release of the year.

Criterion Rating: 10/10

Tokyo Drifter, Seijun Suzuki, 1966

Of the films that Seijun Suzuki would make for the Nikkatsu studio, Tokyo Drifter was one of the wildest, audacious, and visually stunning, yet it was also one of the most incongruous for both Suzuki and Nikkatsu. It was a bold visual statement that happened to also be a complicated yet predictable action film.

The opening is in black and white, with thugs beating up Tetsu, the hero, who is trying to make a clean break from the yakuza. They leave him bloody and beaten in this depressing, black and white wasteland. Tetsu picks himself up, finds a toy gun between two rail cars that happens to be in color, and calmly says “Don’t get me mad.” From here we leave the old world, the black and white world, for a world that is full of vivid and at times overwhelming color.

The plot is almost unnecessary and at times it is nearly incomprehensible. Rather than bog us down in details, the plot is basically a way to transition from one action sequence to another. They skip ahead in time rather than wade in exposition. We know that there are rival gangs that are trying to get over on another, and Tetsu is caught between them. He becomes such a fearsome enemy that all the gangs target him, yet he is able to elude them. Always. He is the Tokyo Drifter, the ultimate badass, a killing machine that cannot be caught, contained, and of course, cannot be killed no matter how hard they try.

What separates Tokyo Drifter from all the other Nikkatsu teen films that were coming out during this period is the vivid visual style. Suzuki uses flamboyant colors whenever he can, usually loud and bright colors, the types that were being used in pop art –- purples, pinks, yellows, blood reds. Even though the sets are just as unrealistic as the plot, they make this for an aesthetically pleasing and thrilling ride. You can turn your mind off, get lost in the eye candy, and root for the hero to triumph over his enemies.

The rival gangs and their real estate shenanigans are the embodiment of evil. They claim that “money and power rule now. Honor means nothing.” They have no redeeming qualities whatsoever, and exist completely as flattened villains. This works as a way of hero worship. As bad and bumbling as his enemies look, Tetsu just looks cool, calm, and elevated by comparison. In one scene he takes on multiple opponents, which is odd given that this is a yakuza and not a samurai film, but the choreography is reminiscent of how Zatoichi dispatches several enemies at once. You have to suspend enough disbelief that these people wouldn’t be wise enough to just take a few steps back and fire their guns at Tetsu. This is not a realistic world.

In several instances the style resembles that of a Spaghetti Western. There are long shots showing Tetsu drifting at some location, and his coolness is shown in close-up wearing his sunglasses and dripping in sweat, just like Sergio Leone was shooting Clint Eastwood around the same time.

Another similarity with the spaghetti western is that the hero has a theme song, but rather than it being scored by Morricone and played as background music when the hero enters the frame, it is actually sung or performed several times in the film. He is introduced as the Tokyo Drifter by an adoring female singer, and the song takes on several other forms throughout the running time. At one time he sings it himself, and another time he whistles what is by that time a familiar refrain.

Much of what takes place in Tokyo Drifter can be dismissed as style over substance with a brainless heroic plot, but there is a message to be had. It is no coincidence that American GIs are at the center of a bar fight near the end of the film. They are abused in this fight, and they react with a silliness that was probably stereotyped for Americans at the time. It may not be as explicit as other films, especially Gate of Flesh, but Suzuki appears to be lamenting the modern world that the Americans have created since the war, with their values of money over honor.

This is one movie that cannot be spoiled because it is completely predictable. It is difficult to criticize it for being ridiculous and over-the-top. Is that okay? Can we excuse this one for being silly, while we condemn other poorly written films? Yes, I think so, because this one has no intention of being anything other than pure fun. It is not aiming at literary high art. It attempts only to be escapist and bedazzling, and on that level it succeeds.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements:

Seijun Suzuki and Masami Kuzuu – This is a 2011 interview with the director and Assistant director. Suzuki saw this as a pop song movie, which it was. In some ways it could be considered a forebear to the music video. He said that they did not put as much thought into it as we might expect today. They were on a quick production schedule, so they discussed shot selections the night before. Their intent was to take the script and make the mundane seem interesting. Suzuki focused exclusively on style, and did not get much funding because his movies were not expected to be hits. He thinks that because they did not have money, they were able to get more creative. The vibrant colors were intended to highlight the pop song.

He denies being influenced by westerns, even though he did watch and admire them. This is one area where I think you have to take his denials with a grain of salt If he grew up watching westerns and this film ends up being full of similarities to the genre, then he was undeniably influenced by them, whether he realized it or not.

The film production revolved around star system. The studio intended to make Tetsuya Watari a star, and that is another reason why he was portrayed as heroically as possible and received flattering shots and poses. They even reshot scenes to heighten his presence.

The studio was against his films, especially this one because they too weird and surreal. The first version had a green moon in the final scene, which the studio made him reshoot, again making Watari more prominent, which he obliged. ‘What else could he do?’ he asks, laughing.

Seijun Suzuki – Here is was interviewed as part of a career retrospective in 1997. He started as a contract director doing B movies before being given the opportunity to make features, which is when he started making innovative genre films. He could not refuse too many scripts, and really why would he since they were all pulpy entertain films anyway? There were no perfect scripts, so he simply changed them as needed.

He tells some funny stories about Watari. He had orders to make him a star, but the actor was not experienced on the set. Many times he had trouble remembering his lines, and sometimes an AD would have to sit outside of the frame with a broom anf hit Watari in order to make him remember his lines.

Criterion Rating: 5.5/10

My Winnipeg, Guy Maddin, 2007

People can be extremely protective about the definition of a documentary. There are some purist that insist that the only real documentaries are cinema vérité, where the camera is a mere fly on the wall and the directors do absolutely nothing to obstruct real life from happening. Of course people have been testing that definition for nearly 100 years. Robert Flaherty is famous for casting actors and staging the action, yet his documentaries like Nanook of the North and Man of Aran are seen as revolutionary.

While many have stayed true to the essence of the documentary, the envelope has continually been pushed over the years. Errol Morris broke a major rule by actually reconstructing real events for The Thin Blue Line. Today the definition of a documentary has been stretched even further. With My Winnipeg, Guy Maddin did not so much as push the envelope, but tore it up into little pieces, ate it up, and regurgitated it. And it is magnificent.

First, let me get a disclaimer out of the way. Guy Maddin is not for everyone. I had seen two of his films previously, The Heart of the World and The Saddest Music in the World. In both I recognized the talented craft of a filmmaker who had studied his film history, especially black and white silent film. These films were a mixture of silent film with David Lynch. I preferred “Heart” over “Saddest”, respected both and loved neither. They were intriguing experiments and not much more. Despite the accolades, I skipped My Winnipeg until now.

Another disclaimer, I love documentary and could care less about the purity. I love Flaherty, especially Morris, Steve James, Berlinger & Sinofsky (R.I.P.), and everyone in between. If someone wants to experiment with form in order to make a point, whether for the purpose of art or revealing a truth, then I say go for it. One of my favorite documentaries of the last several years is Exit Through the Gift Shop, which may be a complete farce. It has some truths, because it talks about graffiti artists whose work exists, but we ultimately do not know what is truthful. We may be the subjects just as much as those on screen. The same could be said with Guy Maddin’s documentary.

My Winnipeg is both a love letter and hate letter to Maddin’s home town. Ultimately it is a little bit of both. He loves the uniqueness, the absurdity, yet hates the cold, the monotony, and how it reminds him of the symbolism of his childhood, such as the furs, the forks, and the lap. Don’t worry if that last sentence doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t make too much sense in the film either.

The film is rooted in Maddin’s own life. He recreates his childhood using actors to play his mother, his dead brother, and even his dog. They stage much of it at his recreated childhood home at 800 Ellis. Since his father died, they pretend that his body was exhumed and buried in the living room.

Maddin provides the narration, which begins with him riding a train through Winnipeg, and the voice is his own reflection of the city. As he narrates in his monotone voice, he intersperses archival footage, maps, quick shots of furs, laps and forks, with scenes of him trying to stay awake on the train. In this manner, the style is similar to the other Maddin films, with nods to silent films (weird title cards), quick dissolves between different types of footage, grainy film, shaky camera work, and the scenes cut back and forth from the train to his home, to the stories of his childhood and of the city. This is not like any other documentary.

It is immediately apparent that Maddin is playing with the truth, not just of his own life, but the entire city. He states some facts, one of which is that Winnipeg has 10x the sleepwalking rate of any other city. Of course that cannot be true. How is it even measurable? Yet this “fact” plays into his train-riding reflections of the city that in many respects resembles a dream world. He also claims that Winnipeg is the coldest city in North America. This is partially true depending on how you measure. It is the coldest large city. There are a few towns in Nunavut that would blow Winnipeg doors off. Maddin’s intention, however, it is not presenting an absolutely factual representation of the city. How much fun would that be anyway?

As he ventures away from his own history, he looks deeper into the city. “Winnipeg!” he says, as he introduces another absurdity, like not being allowed to keep any old signage. All the old signage is kept in the signage graveyard. He talks about a TV show called Ledgeman, where every episode has someone standing at the edge of a ledge, and every show ends with a suicide. Is that real? You can easily Google it to find out. If not real, then what is Maddin trying to say about his city? The TV show is not real, and I think this is part of the hate letter to his city, the fact that people would be entertained by people leaving their city in one of the most gruesome ways imaginable.

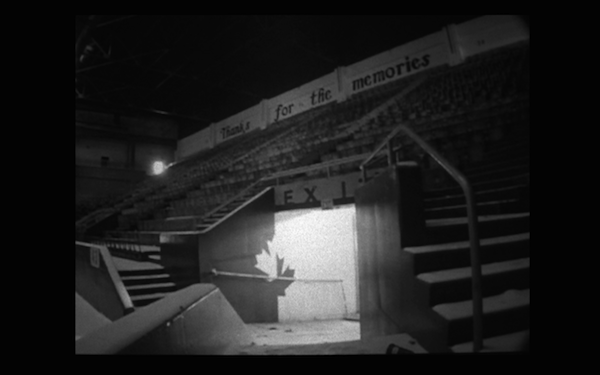

There are other tidbits of “facts,” some more absurd than the last. He talks about the MTS Centre, or the MT Centre with the S flickering on and off so that it really says “empty center.” This was the hockey arena, but has become a betrayal because Winnipeg’s market could not sustain an NHL hockey team, so it was demolished yet stilled fielded a team called “The Black Tuesdays” that consisted of former players aged 70 or older, who played hockey amid the wreckage, sometimes with the wrecking ball actively destroying the arena. Maddin also claims that he was born and raised in the Centre. He was nursed in the wives room, and loaned out to visiting teams as a stick boy.

Some of the above paragraph is true, some embellished, and some outright lies.

Finally we get to the horses, the lovely and beautiful horses. I am not going to delve into this story because it is such a terrific scene and needs to be seen without description. This scene also has a little bit of truth, a little bit of embellishment, and of course, some lies.

Some events seem to be absurdist revisionist history, but are absolutely true. That’s part of what is gorgeous about this documentary. Not only is it engaging and fascinating, but it is a mystery. One could spend hours trying to fact check the documentary, and some probably have, and still could not tell the entire truth from the lies.

There is one telling line near the beginning of the film. “Everything that happens in Winnipeg is a euphemism.” Of course this is not literally true. Plenty of true things happen every day. Perhaps everything that happens in My Winnipeg is a euphemism.

Sometimes strange is truthier than fiction. I loved this movie.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements:

Cine-Essays: These are a series of short essays that Maddin refers to as little “points” that when finished point by point, will encompass Winnipeg. The topics are puberty, colours, elms, and cold. They are, very much like the film, indescribable and inexplicable, but just as much fun.

Guy Maddin and Robert Enright – This is a 52 minute conversation from 2014. He talks about the evolution of the project, and of course, about the factuality of the piece.

The documentary was commissions by Michael Burns for the Documentary Channel. Maddin was fascinated by trains and wanted to use this as the basis to show that Winnipeg is the “frozen hellhole” that we know it is.

He describes the mythologizing as “embedding the stories in emulsion.” It has been called Auto-Fantasia. The debate whether something is really documentary was mostly settled. He cites Herzog who presented “ecstatic truth.” Truth uninhibited is different than truth exaggerated, and that’s how he feels about My Winnipeg.

Even history is flawed because it is the victor’s viewpoint. If they look at the other side, it gets romanticized.

He cites influences, notably Chris Marker, although he does not want to compare himself to Marker. He was also inspired by Fellini’s I Vitelloni. He also references Detour because he cast leading lady Ann Savage as his mother. He does not make the connection, but one could connect the unreliable narrator of Detour with Maddin himself in My Winnipeg. He may be the least reliable narrator in any film.

Of course he does talk about which parts are real and fake, yet in a playful manner. He jokes that he would always get asked the same questions at festivals and screenings, so he challenged himself to always give a different answer. He does tell of some things that were real and embellished, but you can tell that he is answering carefully and could be giving different answers. Even as an interview subject, he is not the most reliable narrator.

”My Winnipeg:” Live in Toronto – This bit shows a screening at the Royal Cinema in Toronto with Maddin providing live narration. He felt nervous. He was told it is normal to feel terrible before and great during. He was surprised how he got big laughter during certain scenes.

Short Films:

Spanky: To the Pier and Back (2008)

This is a film about his dog Spanky, the same one he used as a replacement in the film for his childhood dog. Sadly, this turned out to be his last walk with the dog, as he died shortly afterword. What’s odd is that Maddin calls it an artless film, but I have to call him out on that statement. This is the most interesting dog walk to a pier and back that I’ve seen. Like his feature films, he uses a lot of quick cuts, and frenetic, sweeping camera motions. 8/10

Sinclair, 2010

This is a film that would be incomprehensible without the intro. Maddin was angry about some political, racist issues in Canada. Bryan Sinclair was an Indian, but had a treatable condition and was in the hospital, only to be found dead later. This film is the perspective of Sinclair in the waiting room. 5/10

Only Dream Things, 2012

This was developed for the Winnipeg Art Creative. He recreated the bedroom where he lived and used sounds that he remembers. The movie was dreamlike, with the typical Maddin style, only in color. The dreams themselves are more vivid, alternates between foggy dream state. In a way this film reminded me of someone who goes crazy with Photoshop filters or Instagram. 3/10

The Hall Runner, 2014 – This was one he was hoping to make into a feature but he did not get it off the ground. The film follows hall runner rugs with Maddin narrating. 5/10

Louis Riel for Dinner, 2014

Riel was a politician, and one of the founders of Manitoba. This was an animated short in which Louis Riel was a duck that could not be eaten. This one cannot be described and must be seen, and is probably my favorite short on the disc. 8/10

This was a treasure trove of riches and a nice, recent discovery for me. I expect this will be one of my favorite releases by the end of the year.

Criterion Rating: 9.5/10

In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima, 1976

In the Realm of the Senses is shocking, vile, gruesome and absurd, all of which were intentional. It meant to provoke us (and Japan) away from our mundane social norms, like a lot of 1970s filmmakers were doing across the globe. With the Japanese fierce censorship code, this film is even more shocking, and it reveals something about their moral code given that it still has not been shown in its uncut entirety today.

However disturbing, it is essentially a film about love. To most people, including myself, this type of love would be revolting and unfathomable. The woman has an unquenchable sexual thirst, while the man serves as a vehicle for her insatiable desire. As their relationship progresses, the ordinary becomes boring and she continues to ratchet up their activities. This makes for a more controversial and shocking film as it goes along, but it is fitting in how the plot develops and resolves.

When I first watched it, I found it shocking and amusing. That was also intended. Scenes such as when children throw snowballs at an older man’s genitalia add very little to the plot, and serve only to further provoke. The older man in question is only pertinent because he recognizes Sada, the lead character, as a former prostitute, although that could have been handled differently.

The sexual acts get more amusing, whereas the climax (no pun intended) and resolution are outlandish and way over the top. I was surprised to learn later that this was a true story. This one needed some time to settle and appreciate, and thanks to a good number of Criterion supplements, I received plenty of context and analysis.

Even though the description of the film would sound like pornography (and in a way, it is), the difference is that this was created and produced by professionals and has an artistry that lessens the stimulation. The set designs and photography are gorgeous, and even though the characters are doing unsettling things with their bodies, they are framed by an auteur. One such example is during the wedding scene. The man who had previously conducted the ceremony is doing some sort of celebratory dance. The camera pans upward so that he and his dance are the focus of the shot. It settles there for a time as he continues dancing, and then pans down to his feet where an orgy is taking place among the entire wedding party. Again, it is meant to shock and not titillate.

From here on out, I have to discuss the ending. Please stop reading here if you are spoiler averse.

As domestic, routine sexual activity becomes boring, Sada veers into sado-masochism territory. This is introduced through her earning her living as a prostitute, and encouraging her client to slap her repeatedly. She enjoys this so much that she brings it into her own bedroom. This leads even further, and she eventually gets fixated on choking. She likes the sensation when he is being choked during the sexual act. Even this eventually becomes mundane, and they have to go even further.

To understand Kichi’s behavior and final sacrifice, you have to understand a little bit about Japanese culture. They have a certain fascination with it, and they think of it as courageous to sacrifice one’s life for another. The most obvious examples of this ideology are the kamikazes in World War II. We also decorate our heroes, but in Japan it is different. It is truly honorable to die by one’s own desire.

When Kichi tells Sada that next time she should not stop with the choking, he is committing his final sacrifice. This is him letting go, giving everything he has in order to please who he loves, because there is nothing else within him that can satisfy her any longer. From a Japanese perspective, it is an honorable, if unconventional, way to die.

The ending is foreshadowed throughout the film. She has been characterized to have a violent streak, and had even threatened to cut off his manhood earlier in the film. There are scenes where she uses sharp objects, such as the time she holds a knife in her mouth, or the fantasy she has of cutting up Kichi’s ex-wife. Once she realizes that Kichi is gone, she simply takes what she feels belongs to her, his manhood. Again, this is shocking and grotesque, but in the context of their relationship, it is another act of love. She is taking her favorite part of his, and what’s left is her intense loneliness.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements:

Commentary: – This was a fantastic commentary from film scholar Tony Rayns, which was not expected. He begins by disclaiming that he will not be commenting on the sexual acts themselves, and he takes an academic approach to the film that was enlightening and refreshing.

He reveals that the popularity of artistic sex films in America prompted the project to start. Japanese had many sex films, but that’s not what they were going for. This was a true story, and the filmed version a lot more similar to the reveal events. Not every scene was true, of course, but the broad strokes of the plot were real.

They were a working class couple, not very educated, and they continue an erotic tradition that goes back centuries until Edo period. It stopped around Meiji period, where outside morals infringed on them. Because of this, In the Realm of the Senses is in part a political film, but that is difficult for Americans to tell unless they have a good sense of Japanese history.

Oshima drew on the trial transcript and the Sada story that was told after she was released from jail and published later. Oshima had made other provocative films, but this was his first from the female perspective. Of course it would not have made much sense to tell this story from a male point of view..

The sexual pleasure on film is all from Sada, and not from Kichi. He is never shown or heard actually in an orgasmic state. Even in the scene where his pleasure is shown in physical form, he does not moan or shudder. It is shown from her perspective and she takes the pleasure in his discharge, not him.

The true story is that after Kichi dies, the story becomes popular and people side with Sada. That is strange given what we’ve seen on film, but it is not too abnormal given Japanese culture. He gave his life for her.

Interviews:

Oshima and His Actors – This was a 1976 interview with the lead actors and Oshima for Belgian TV in 1976. Fuji does not actually speak in this interview, and Oshima does the majority of the talking, He says this was the first hard-core pornographic film in Japan. The other ‘pink’ films, as he calls them, were tame in comparison.

Eiko Matsuda, who plays Sada, speaks briefly and seems uncomfortable. She had an inferiority complex when she heard about the film. It helped her work through it, and so she feels it was her destiny.

Tatsuya Fuji – The lead actor was interviewed for Criterion in 2008.

French title was “Empire of the Senses” which is a better fit. He felt that his relationship was very much a dual, two-person empire, and their desires are their own. They should not be judged.

He said not many actresses could have taken such a role, not just because of the ability, but also the courage. Eiko had worked in underground theater and had a different perspective than most actresses.

Oshima created a relaxed and gentle atmosphere on set. He was very polite and let the actors be. Usually the set would be cleared for the sex scenes with just the actors and Oshima present.

He talks about how the sense of dying in Japan is different. They see life as a “a fleeting dream.”

Recalling the Dream – Even though this segment is under the Interview category, it is more of a documentary. It is a 40-minute segment that talks with a number of people who were involved with the film from behind the camera.

French distributor Dauman had imported Oshima’s Death by Hanging. He then moved from distribution to production, and it was Dauman that wanted an erotic film. Oshima was a leftist and it was thought that he would use sexual imagery as a political statement, but it turned out to be a conventional love story, albeit with political overtones.

They got around French legalities because they were technically French sets. All the film and negatives went to France. It was not developed in Japan during or after filming. It had been developed in Japan, the lab would be charged with indecency. It was unusual for the crew to not see dailies or any footage during the shoot. They just had to trust that Oshima was getting what he needed.

When the filmmakers and crew returned from France after the initial release, customs and police waiting for them. They had to screen the print to customs because it was a customs bond, which was the only time the film was ever screened uncensored in Japan. It was an audience of 50 people. For the Japanese release, they put a black bar on the entire lower part of the frame to censor the sexual activities.

Police wanted to go after Oshima for something and couldn’t. Instead they went after the script. The result was that Oshima apologized for stimulating the judge, police and authorities in the hearing. It sounds today like he was being sarcastic, but that was actually part of the deal.

Censorship is more liberal in Japan now, but they still cannot show the uncensored film. The biggest victory was being able to show the castrated penis uncensored.

Deleted Footage – Most of the scenes were simply extensions of existing scenes and were not too necessary. For instance, they extend a scene with her playing music at the inn to hide that they are having sex. The most notable deleted footage was that of the non-fatal choking scene and just after Kichi’s death. That scene is extended with Sada acting frantically and looking around, presumably to make sure nobody was around. They probably shortened that scene to make it seem more like love and less like a crime.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

Les Blank, Always For Pleasure. Part Four.

GAP-TOOTHED WOMEN, LES BLANK, 1987

Again, we have a Les Blank topic that comes completely out of left field. Who would dream of filming a movie about something as minute as a slight wedge in between someone’s mouth? Les Blank was that man, and based on what other topics he approached, he must have been unusually attracted to women with the dental distinction.

The big question is whether there is some mystique to gap-teethed women. Are they sexier than girls with a block of bright and shiny whites? That’s probably in the eye of the beholder, just like some people with find various imperfections attractive.

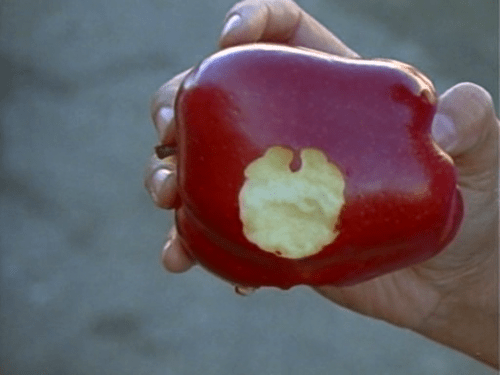

Blank takes the topic further and uses it explore the concept of beauty and self-image. He opens with a girl who bites into an apple with her gap-teeth, and proudly leaves her ‘signature’ in the piece of fruit. Chaucer is referenced aplenty, and sometimes in the manner that he adored gap-toothed women. The Wife of Bath had gapped teeth, and she also had five husbands and countless other lovers. Her affliction did not leave her for wanting. Others have studied the term and traced “gap” back to the word “gat,” which meant lecherous, casting not the most favorable shadow on Mrs. Bath.

Some women are self conscious about their gaps. A lot of dentists consider it a flaw and aggressively will try to convince women to close them (or maybe they just want the business). They are more common in other words, such as Indian, where one lady says “half of India has gap teeth.” That could be due to a lack of dentistry as well as any cultural preference.

To balance out those with image problems, there are plenty of famous individuals that are considered beautiful. Lauren Hutton made a living out of her gap-tooth, and appeared in the movie doing street interviews. Madonna, also gap-toothed, is likely also proud. At last check, she still had the gap, but she did not choose to appear in the movie. Hutton’s message is to accept one’s own imperfections and turn them into your own uniqueness. Others take it further, such as one lady who screams for “Gap Pride!”

Blank gets some points for pursuing a topic that most could not even conceive of, and using it to explore the incomprehensible topic of women’s self-image and male attraction. Well done, Les.

Film Rating: – 8/10

Supplements:

Mind the Gap – This piece shows his office, cluttered with stuff he loves. Includes gap-toothed women, garlic, and red headed women and was going to make a movie about the latter. Susan Kell talks about his fascination of Chaucer, and the wife of Bath.

They had a Casting call advertisement and had the phone ringing non-stop. Who knew there were so many people with gap-teeth and eager to show the word? Te gist was that most women were excited about celebrating what had been seen as a flaw. They unsuccessfully tried to get Madonna. They also tried for Whoopi Goldberg, who was local to Berkeley and not as famous. She probably would have done the film, but her career blew up during the filming and she was no longer available.

YUM, YUM YUM! A TASTE OF CAJUN AND CREOLE COOKING, LES BLANK, 1990

Les Blank has some great titles, and this one fits the subject the best. I would say the vast majority of his documentaries have some element of food, even if it is not the primary topic. He just loves food.

This time he returns to Cajun country to focus exclusively on the cuisine. We meet up again with an older Marc Savoy, who we first met on Spend it All. He throws a bunch of ingredients in a pot that are then cooked over a country wooden fire. It is called “Goo Courtboullion,” which means absolutely nothing to me, but looks like the most delicious thing anyone could taste.

The guys out in the wilderness haven’t heard of Paul Prudhomme, which turns out to be a good time for a transition, and they then show him signing books in New Orleans in the next scene. He is the owner and celebrity chef of K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen. What’s interesting about Prudhomme is that this is ages before the Food Network, Top Chef, The Cooking Channel, and the concept of celebrity chefs. Prudhomme was one of the originals, and he along with others (Justin Wilson, Emeril Lagassee) popularized Cajun cuisine in the kitchen. When one watches this documentary — and perhaps many TV executives had — it is easy to understand why.

They cook a variety of dishes, with a focus on whole foods and nothing manufactured. One lady dismisses garlic powder, saying, “that’s the new stuff they got. No good.” Blank, ever the garlic aficionado, would most definitely agree.

Many more dishes are made, including a variety of Etoufees, each looking more delicious than the last. I seriously challenge anyone to watch this 30-minute documentary and not eat something during or immediately after.

Marc Savoy reappears to presciently comment on Louisiana cooking from outsiders. He ordered Cajun fish at Disneyland. The fish itself was fine, but they covered it in a black pepper that made it inedible. He actually took the fish to go, removed the pepper and ate it. I wonder what he would make of all the Cajun restaurants that have sprouted up all over the country? Would he take their finest dishes, eat a bite and then customize the rest later in his hotel room? My guess is yes.

The best quote is:

“What’s better than a bowl of gumbo?”

“Two bowls.”

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements:

Marc and Les – When recruiting Savoy’s participation, they called him up and said “come on over, making gumbo.” Marc credits Les for meeting his wife Anne, which was sort of a half-truth because he met her at a festival that he wouldn’t had attended if not for Les. Les would remain friends with a lot of his subjects. Savoy was no exception.

THE MAESTRO: KING OF THE COWBOY ARTISTS, LES BLANK, 1994

The overall theme of “Cowboy Artist” Gerry Gaxiola is that he does not paint for money. Like with Anton Newcombe, made famous by Ondi Timoner’s Dig!, he is not for sale. The continual reminder for Gaxiola in the film and the features is that for him, art is a religion and not a business.

What’s odd about Gaxiola is that the grew up in San Luis Obispo. Even though he grew up in a ranch, southern California does not exactly scream cowboy country. He speaks without a southern accent and his values are more common in Berkeley, where we resides, than say, Texas or anywhere else in the deep south. Yet he travels with a Cowboy getup, complete with the hat, boots, and even utility belts that he creates himself to holster his “guns,” which would be paintbrushes. Is he an artist or a gimmick? If you ask him, the answer would indubitably be artist, but Les Blank’s portrayal leaves the question on the fence.

He began having a Maestro Day, which would be a daily celebration where he would invite crowds to see him perform. He would do some artistic endeavors, like a “Quick Draw” where he would paint at warp speed. The rest was more performance, including singing and dancing. He would get the crowd involved, awarding best-dressed cowboy. There would be treats, and it sounds like a fun day for the family. Despite the success of Maestro Day, he quit it after 13 years because he was moving more in the direction of entertainer than artist and that is not how he wanted to be seen.