Category Archives: Film

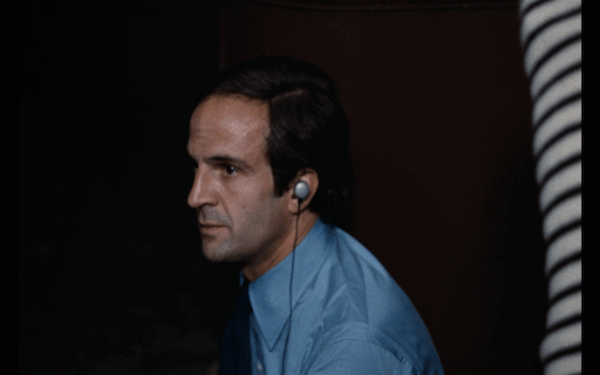

State of Siege, 1972, Costa-Gavras

Would it be safe to call Costa-Gavras an advocate filmmaker? That’s a tough question, which I am not sure whether I or even he could answer. He was unquestionably a political filmmaker, and he dabbled in subjects that were often controversial. If he was not angering the communists from The Confession (my review), he was angering the CIA by taking unveiling the blemishes of the Cold War. He certainly had his political views, and those did take shape in his films. We learn from the supplements of this disc specifically where he found the motivation to make this film, and it was not based on a positive impression of Americans.

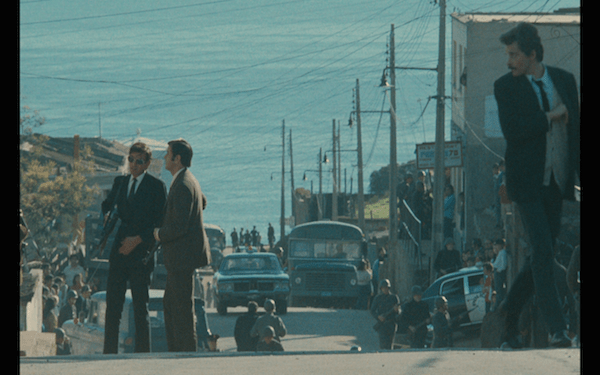

The subject of State of Siege is the activities of CIA-like organizations that were being undertaken in various South American territories. The plot is about an American, Philip Michael Santore (Yves Montand) who worked for USAID as a “Communications Expert.” I used quotes for his job title because we’re not sure exactly what he did during his various travels. Was he a benefactor or was he a terrorist? That answer is not provided, although it is strongly hinted that he was at least aware of the latter activities, if not a direct participant.

I am about to reveal a major plot point, but not to worry. It is not a spoiler, at least unless you consider the beginning of Sunset Blvd a spoiler. Our operative friend, Mr. Santore dies at the beginning of the film in Montevideo, Uruguay. The film begins with a shot of a shiny Cadillac followed by a series of roadblocks and an exhaustive search by the authorities. We do not know what they are searching for initially, but minutes later when they discover a carcass in a car, we know. Soon after the discovery, we see a highly ceremonial funeral, with an American flag draped over the casket. We get the impression that something is awry because the archbishop and academics are not present, yet the funeral is well attended, implying that this was the passing of an important, political person.

Is Mr. Santore a good person? That’s another tough question. He comes off sympathetically, some of which has to do with the ever-likeable performance by Yves Montand, who was also a popular political figure at the time. As the film flashes back to the kidnapping and interrogations, we wonder which is the truly righteous, Santore or his kidnappers? He is accused of, at the very least, knowing of torture, and at worst, guilty of perpetrating war crimes. Yet he is part of a system. If he was guilty, was he simply doing his job? That does not mean that he deserves to be kidnapped and killed. His captors also are sympathetic. We learn through Santore’s observations that they do not intend or want to kill him. They are merely fighting a battle with limited weapons. We are not spoon-fed who to like or root for. One could make an argument that the kidnappers and kidnapped are both right to some respect, and simply pawns in a chess game between people far more powerful. The real evil could be the state that infringes on the rights of the people, or those who choose to not compromise and therefore through inaction lead to the creation of a martyr.

What is clear is that Costa-Gavras was aware of the goings on in Latin America and elsewhere. With the benefit of hindsight, even the citizens of the USA can agree that this was a dark period of history and we do not condone the actions of the government. Even then, the average Joe was not aware of what operatives were doing overseas, either to protect American commercial interest, or as a product of Cold War rhetoric. Costa-Gavras is unquestionably critical of these puppeteers, but he is also critical of those who infringe on the liberties of others. By using some excellent location shots, he shows how the police force is both ruthless and inept. In some instance they are bumbling, such as in a humorous scene where the police chase after radios that are broadcasting propaganda, only to find the sound coming from a different radio. This is one of the few moments of levity, and it comes at the expense of the “Keystone” cops.

State of Siege is sparse on action and aside from these large location shots, often uses minimalist filmmaking methods. Like with The Confession, the real drama comes from the conflict between the revolutionaries and their captor. There is no suspense as to what the outcome of this encounter will be, but what keeps us enthralled is through the character examination, and whether he is being honest about his innocence or whether he is a liar. The flashbacks and the pinpoint questioning lets us know that the captors know plenty more than they let on, but are they right about Santore or is he yet another innocent casualty in the continual Cold War? We aren’t told, and this is yet another reason why Costa-Gavras was considered the master of the political thriller. He makes scathing political statements, but he creates complicated characters and blurs the lines between good and evil.

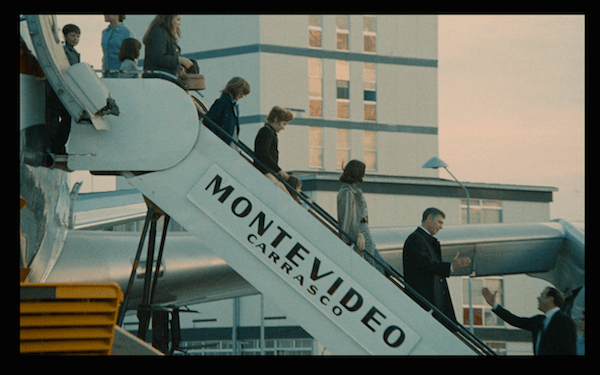

State of Siege is not a perfect film. I had some quibbles. One that jumped out at me is that they used similar airport greeting scenes as a way of showing how Santore traveled the world, but the only difference between many of these stops is the country name on the staircase that rolls up to the plane. It is obvious that the same location was used, probably over a short period of time, and they simple changed the angle and the sign. There are other minor issues, but there is more here to like than dislike. Even if it is not the perfect film, it seems to capture the spirit of CIA activities in Latin America and elsewhere from the perspective of the people who experienced it. This makes it an important film, even if not a great one.

Film Rating: 7.0

Supplements

Costa-Gavras and Peter Cowie: 2015 conversation.

The idea originated with an American advisor that CG was aware of in Greece. This was a tough guy, probably the stereotypical CIA spy. He was the real deal and was killed in his car later.

Based on Dan A. Mitrione, who was part of AID, which was a sister or daughter program to CIA. Mostly the story of the subject was the same, but the name was changed.

You can tell he is a true student of politics and governments as he cites various countries and how they came undone by their violent nature. He is referring more to Nazi Germany or Stalinist Russia, but he is perhaps making a gesture towards America’s checkered past and present.

NBC News Broadcasts on Dan A. Mitrione:

This seven-minute montage of news footage shows the real story, but from the American perspective. The anchor talks about the kidnapping, the search, the ultimatum, and most of what we see in the film. Even though it is clearly biased towards Americans and wanting the citizen freed, it also states that the Tupamaros were seen as Robin Hoods that were not violent, but that impression was changing with this incident. Costa-Gavras seems to capture that as well, that they do not intend to be violent, but only resort to it out of necessity.

The supplements are slim and this fits better as a supplement to The Confession. Even though it isn’t the most stacked disc, it is well worth getting for the film and the transfer.

Criterion Rating: 7.5

Episode 8: Hiroshima Mon Amour & Romance Across Borders

Aaron, Mark and Martin go in-depth as they explore romance in Alain Resnais’ debut film, Hiroshima Mon Amour. We look at how the sensuality and romance speaks to the tragic events and horrors of the atomic age, while they explore each other’s cultures through a brief relationship.

Or listen here to it here:

For other apps or mobile devices, try this link.

Or direct download/listen to the MP3.

Show notes:

Special Guest: Martin Kessler from Flixwise. You can find him on IMDB, Twitter and Letterboxd.

Outline:

0:00 – Intro, Shout-Outs, Letterboxd Discussion.

9:55 – News

20:20 – Hiroshima Mon Amour Discussion

1:11:05 – Romance Across Borders

Intro:

Letterboxd lists:

The Criterion Collection (thanks Arik!)

The Eclipse Series (thanks Arik!)

1001 Movies to See Before You Die

AFI 100 Movies, 10th Anniversary

Oxford History of World Cinema

News:

Rome: Open City Coming to iTunes.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s newest will debut on @mubi after its New York Film Festival premiere.

Carlotta Films Box Set for Rivette’s OUT1.

The Sonic Landscapes of The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Hiroshima Mon Amour:

Hiroshima Mon Amour

Where to Find Us:

Mark Hurne: Twitter | Letterboxd

Aaron West: Twitter | Blog | Letterboxd

Criterion Close-Up: Twitter | Email

Top 20 of 1987

The series continues. As we head toward the late-eighties, there seems to be a lull. There are some international titles that made the cut, and a lot of the American titles range from somewhat artsy (Raising Arizona, to mainstream Princess Bride, to guilty pleasure (Spaceballs). Okay, maybe two guilty pleasures with Eddie Murphy Raw, but I still say that is one of the best standup comedy films ever.

There are only two that I would call American indies, Matewan and Housekeeping. Okay, three if you count Les Blank’s Gap-Teethed Women, but he almost defies categorization. There will be more of those to come as the indie revolution was soon underway. As I scoured my list, I found a lot of John Hughes wannabe films at the bottom of the pile. That cycle was beginning to run its course and American cinema was in a transitional period.

Even though I consider this to be a weaker year than most, the top five can stand next to any year. It is no surprise that none of them are American films. There are a handful of international films that I have yet to see, and really want to. Pialat’s Under the Sun of Satan is supposed to get a release sometime soon, but not in time for this poll. I had one Rohmer film on the poll, but I have a feeling it would be two if I had seen Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle. Either way, I think it is safe to say that 1987 was a decent year for international film.

1. Au Revoir Les Enfants

2. The Last Emperor

3. Withnail & I

4. Where is My Friend’s Home?

5. Wings of Desire

6. Eddie Murphy Raw

7. The Man Who Planted Trees

8. Boyfriends and Girlfriends

9. Princess Bride

10. Spaceballs

11. Broadcast News

12. Matewan

13. Raising Arizona

14. Red Sorghum

15. Less than Zero

16. Wall Street

17. Full Metal Jacket

18. Gap-Toothed Women

19. Radio Days

20. Housekeeping

My last cuts were many this year. It was tough to find a film for the last spot. I considered all of these:

Angel Heart

The Believers

Maurice

House of Games

The Untouchables

Planes, Trains & Automobiles

Cobra Verde

The Dead

Dear America

Maybe the year wasn’t so bad after all.

My Beautiful Laundrette, 1985, Stephen Frears

There have been numerous post-colonial portraits of the United Kingdom, most of which deal with the new class system and how they adapt to this transformed society. Generally when portrayed from the lower class perspective, the story is about having to deal with past and continued oppression, and that they try to subsist when others are born in a more privileged position. In My Beautiful Laundrette, this type of story is turned on its head. The lower class immigrants have come so far since colonialism that they have not only assimilated into this society, but they have essentially become a version of this new, upper class. Rather than be exploited, they find the opportunity to be the exploiter.

Another major factor was Thatcherism (Margaret Thatcher for those not aware). Thatcher ‘s policies benefited and encouraged the upper classes, while neglecting the lower classes. Frears was clearly not a Thatcher fan, and he used minorities obtaining a privileged position as a way of being critical. He stopped short of being racist. In fact, I think the opposite was true, and he presented a balanced and perhaps realistic perspective of the situation. Under Thatcherism, minorities were able to get the upper hand on lower class whites. However, they were still not entrenched as the upper classes. One of the less scrupulous rich minorities at one point says, “we are nothing in England without money.” Through Thatcher’s capitalist policies, it is greed that defines position.

Omar (Gordon Warnecke) is the protagonist, and he sees both sides. He lives both in the white lower-class world through his interactions with Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis) and with the privileged minority status of his rich uncles. He is also exposed to a staunchly anti-Thatcher father, whose political views resemble socialism more than any other. All of these forces tug at Omar, which makes him a captivating and well-developed main character.

Omar finds a Laundromat as a means to his success, and like his rich uncles, he embraces the thirst for money through a strong work ethic and a relentless desire to succeed. Once given the opportunity to manage the Laundromat, he pours everything into this project. What complicates the class-conflict dynamic is that he recruits Johnny as an employee. Johnny is a reformed skinhead and is decidedly anti-Thatcher. He is not racist, but his former “blokes” are. It is telling that the original Laundromat name was “Churchill’s Laundrette,” which Omar and his uncles later change.

One of the rich uncles says that, under Thatcherism, “in this country you can get anything you want. It is all spread out and available. That is why I believe in England. But you need to know how to squeeze the tits of the system.” This is a strange sort of loyalty to a country. It speaks little to their nationalistic pride. To the contrary, they still maintain some of their ethnic identity. It is more a statement that they will use the system to enhance their position, and that includes exploiting the lower class whites like Johnny. They are even proud of that exploitation. Even Omar succumbs to that sensation at one point, finding himself in a socially juxtaposed than what existed 30-40 years prior, and feeling a form of euphoria. It is intoxicating, and that is exactly the type of lure that his father warns against.

Omar and Johnny have a homosexual tryst, which was controversial back in 1985, although is more accepted nowadays. The fact that the two would pair says something about this dynamic. We have a strong main character in Omar who has been raised under two opposing ideologies, and Johnny, who relates more to the leftist of those influences and literally hates the right-wing element. Out of friendship and perhaps his desire for Omar, he does a good job helping develop the Laundromat, and in turn becomes an exploited worker. This conflict would come back into play to great effect in later, climactic scenes.

Writing this today, Daniel Day-Lewis is one of the top global movie stars, and many would argue that he is the best actor of his generation. He was stunning in Laundrette. One thing to keep in mind while watching his performance is that the person is far from lower class, yet he embodies the character with chameleonesque ability, a trait that would seem natural to him in the years and decades to come. The performances are all solid, especially Gordon Warnecke as Omar. Day-Lewis still manages to steal every scene he is in, and it is no surprise that this role would be a breakthrough and lead to plenty of success, although with his talent. It would have happened anyway. Johnny also represents an opposed ideology from Omar. Even though he does fine with the Laundromat, work ethic is not a means to success. He has different ideas about how to achieve wealth, which is crystal clear when he says, “This city is chalk full of money. When I used to want money, I’d steal it.”

This was my second viewing of the film, and the first in many years. I’ve seen other Frears’ projects and respect him as a director, although I would not go so far as to call him an auteur. I was pleasantly surprised by some of the shot selection and direction in this film. He makes good use of camera angles and even has a lot of mirror shots, all of which are important because many of the characters have multi-faceted experiences and perspectives, and I did not even touch on an adulterous Pakistani-English adulterous relationship that speaks more about the relationship between the two cultures as anything else in this film. I was also surprised to see such a rich and textured perspective of class dynamics, which is easier to pick up on in hindsight than it was in the 1980s. Not only is My Beautiful Laundrette a superb film, but it is a document of its time.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Stephen Frears: 2015 conversation with producer Colin MacCabe

He was a middle-aged, working TV director while Thatcher was in power. Lindsay Anderson, Jack Clayton, Ken Loach, inspired the change in UK film (we discussed some of this here), and he worked at the BBC in the 1970s.

Thatcher changed the world for everyone, including for them in TV production. Channel 4 came around, which was mandated by Thatcher. Laundrette was intended to be a TV movie. Hanif Kureishi showed up at his office and explained the script.

He mentions the names of the actors that he considered, all of which are famous now, such as Branaugh, Oldman, etc. Nobody thought Day-Lewis would become a star, but it really happened by him playing this working class character and following it with A Room With a View. Of course Frears says he was very good.

He denies auterism. “How can I be an auteur if making a film about a culture I don’t understand?”

Hanif Kureishi: 2015 interview.

The story is about a boy and a father spending too much time with each other, which reflects Kureishi’s life. This was a traditional story with an uncle leading a youngster out into the world, and he becomes sexualized by this experience.

Kureishi wanted to show the abuses of racism, which he had experienced before, but he also wanted to find his own voice. He called A Passage to India and the Merchant-Ivory films as boring, while Thatcher was destroying the working class.

He was influenced by Derek Jarman, Peter Greenaway, and also Paris, Texas, especially the mirror.

Tim Bevan and Sarah Radclyffe: First feature production of theirs and they founded Working Title. 2015 interviews.

This came at an interesting point in cinema. Channel 4 had started, so independent film began. Music videos were getting popular, which got young people into the industry. Thatcherism also got rid of the unions.

They started as music video company, and to get to know directors, they asked these directors to do music videos.

They talk about how Hans Zimmer did good work and was recognized in Hollywood from this and another movie they did, A World Apart and was hired to do Rain Main, which basically launched his Hollywood career.

They went from film to film, and were focused on that more than running a company. They were basically unorganized and insolvent. They were not paying any bills, just flying by the seat of their pants. They found funding and that established the company as it is today.

Oliver Stapleton: 2015 Criterion interview.

This was cinematographer Stapleton’s first collaboration with Frears and they would go on to make seven more films.

His shooting style at the time was very early eighties, wide lenses, vibrant colors, and very much like music videos. That was in frame of mind when starting his career. He had worked with Julien Temple as well.

When he sees it today, he sees it as very stylized, more than what he did ten years later. He no longer uses the type of extravagant colors that he did then, for example. He was following his instincts, which Stephen was doing as well. They didn’t storyboard, but let the action dictate wheat they would do.

Criterion Rating: 8.5

Episode 6: 12 Angry Men (1957) and Single Location Films

Or listen here to it here:

For other apps or mobile devices, try this link.

Or direct download/listen to the MP3.

Aaron, Mark and Doug explore innocent, guilt, and civic duty by discussing Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men. We also discuss other films that are shot primarily at one location, why these films are often good, and what ingredients are required for a quality film in a single location.

Show Outline:

0:00 – Intro, Welcome, Thanks.

22:00 – Preview of December Releases

31:50 – 12 Angry Men Discussion

1:15:25 – Single Shot Discussion

Show notes:

Special Guest: Doug from Good Times, Great Movies. Twitter | iTunes.

NEWS

Monkees’ Complete TV Series, ‘Head’ Coming to Blu-ray

DVD Beaver Dressed to Kill review.

Toronto International Film Festival

Steve Jobs

Michael Fassbender article.

12 ANGRY MEN

Where to Find Us:

Mark Hurne: Twitter | Letterboxd

Aaron West: Twitter | Blog | Letterboxd

Criterion Close-Up: Twitter | Email

A Star is Born, William A. Wellman, 1937

I am writing this essay about the 1937 version of A Star is Born for Now Voyaging’s William Wellman blogathon. This is actually the first non-Criterion review I’ve written for the site, but it is a great subject and I want to support her event.

Even today, countless people dream of becoming movie stars in the mythical land of Hollywood. However, stardom today is not the same as it was during the 1930s when the star system was at its height. Stars such as Garbo were goddesses. Virtually everyone went to the movie palaces to see their images fill the screen. They were larger than life. During one of the worst economic periods, people dreamed of escaping their meager lives and being both rich and adored.

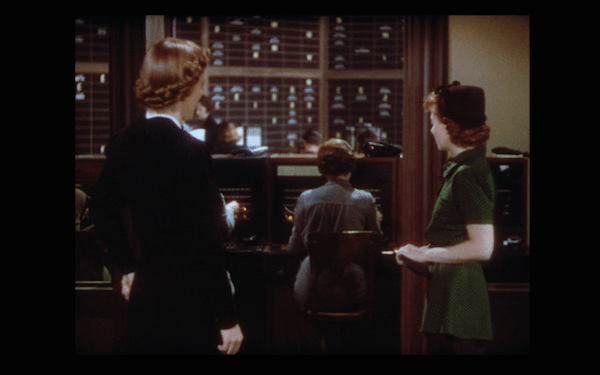

The Hollywood myth became like a Horatio Alger novel — rags to riches. Certainly some people did get a lucky break and achieved stardom, but they were few and far between. In the film, as Esther Blodgett (Janet Gaynor) tries to get a job as an extra at a studio, she is shown a group of operators whose only job was turning down those looking for work. In the real world, Blodgett wouldn’t even get in the door. She was told that the chances of becoming a star was 100,000 to one. I would wager that even then, it was closer to a million to one. Even if the protagonist is a budding star, the film shatters the illusion, and subsequently the glamour of becoming a star. It is unlikely, and if it happens, it is not all that it is cracked up to be.

A couple weeks ago in our podcast on Truffaut’s Day for Night, we explored the concept of Hollywood turning the camera on itself. This practice is called ‘self reflexive’ by academics, and A Star is Born is one of the early examples (also What Price Hollywood? but that’s another story.) Often the portrayals of Hollywood are not altogether positive, and that is clearly the case with Wellman’s film. Blodgett, or as she would be referred to in Hollywood, Vicki Lester, would find that the life of a star is far from perfect.

She gets her break out of luck, and that speaks to Hollywood then and now. Just showing up with a suitcase is not enough to get in front of the camera. You often need to have a connection. Blodgett finds her connection with someone in the industry, and through him, she eventually meets the star actor, Norman Maine (Fredric March). Maine takes to the youngster, and pulls a few strings to get her work in the studio. She becomes Vicki Lester, and you could say that meeting is the titular instance where the star was born. She had the capability and the look. She just needed the opportunity.

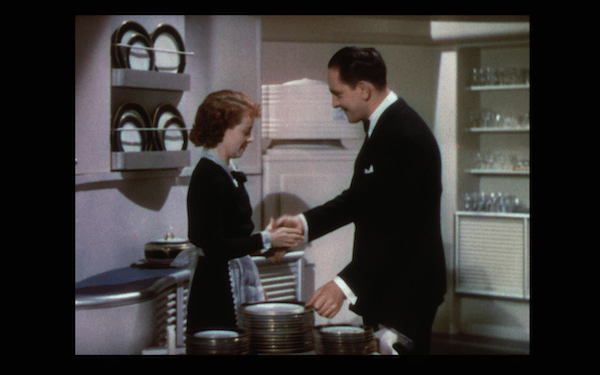

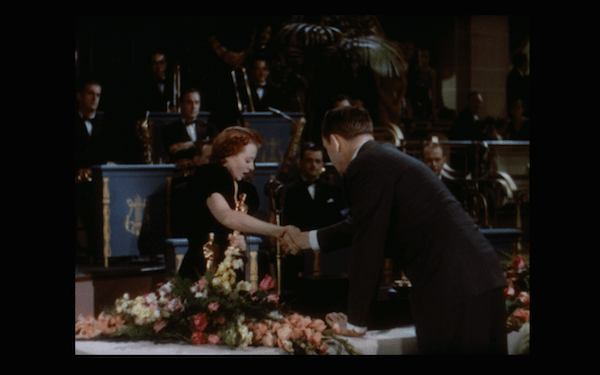

Lester and Maine develop a relationship, which leads to marriage. They star in a film together, and where Lester is terrific and fawned upon, Maine is disparaged. Struggling with alcohol and his own ego, despite his devotion to Lester as her star is rising, Maine’s star is falling. He tries to be a good husband, but at the core, he resents the fact that his wife is gaining acclaim while his career is going down the tubes. He crashes the Oscars when Lester is receiving an award, decrying Hollywood for leaving him behind, and bashing himself for giving what he dubs a Worst Acting award. His tale is tragic and cautionary. The fact that Lester is dedicated and loving to him speaks to her character. While she is becoming a star in the film, she also endears herself to the audience by showing consideration for those around her, especially her husband.

Major spoilers follow this image.

Seeing Maine’s struggles, Lester decides to sacrifice her career. The love and devotion she feels towards her husband is worth plenty more than acclaim and adulation. Maine overhears her when she decides to sacrifice herself for him, and he instead makes a sacrifice for her. Here is where I find the film fascinating. Back in the 1930s, Hollywood was especially in the happy ending business. This ending has a tragedy, although I wouldn’t entirely call it a sad ending. It is more of a bittersweet ending, because Maine recognized that he was holding Lester back, and his sacrifice for her was heroic in a strange sense (even if cowardly).

A Star is Born was not only a well-produced film, but it was also brave. It turned the cameras inward and exposed Hollywood, warts and all, and did not turn away from a challenging ending. There is a reason that this story has been re-made twice, including the 1954 George Cukor version with Judy Garland and James Mason, which was ultimately more successful and probably remembered better today. Even though I really like the performances in Cukor’s performance, and prefer Mason to March, the original is my favorite. This is mostly a credit to the work of people like Wellman.

Yi Yi, 2000, Edward Yang

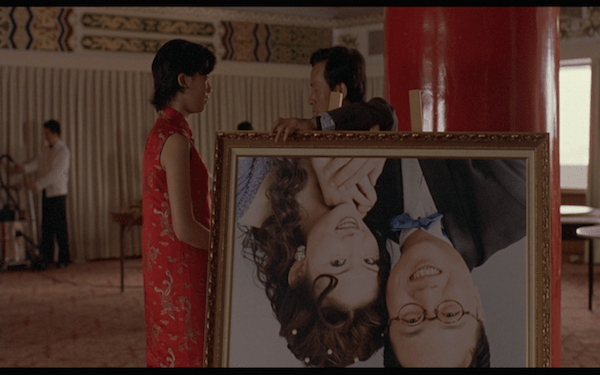

This was originally posted at Wonders in the Dark as part of their Adolescence and Childhood Countdown.

The term “family epic” is not often used to describe a film, not even an art film (at least not post-Ozu). There are plenty of lengthy films about families, but few that are grandiose to share a descriptor with the likes of Lawrence of Arabia. Yi Yi is indeed a family epic film. This is not just because it has a three-hour running time, but rather because it successfully captures the scale of a multi-generation family. Instead of telling a lengthy narrative through the generations, it reveals enough about the characters in the present, by exploring them through a single, binding experience, that it is just as effective.

I chose Yi Yi as my top film for the Wonders of the Dark Childhood and Adolescence poll. This choice may seem peculiar because the film features so many characters from the family, most of whom are adults, that the children are not given the most screen time. In fact, if you were to pick a protagonist, it would probably be NJ, the father figure. However, the children’s experiences mirror and elucidate the actions of the adults, and they flesh out the characters. The children, through their innocence and naivety, also interpreted the events with a perspective that the adults are incapable of, and sometimes their silly inquiries are prescient.

Yang-Yang asks his father, “Daddy, can we only know half the truth? I can only see what’s in front and not what’s behind.” This may seem like a simple, naive question, but it speaks to how humans tend to only look forwards and not backwards. The adults in the film are reticent to look backward, yet the children experience things that the adults have also experienced. In other words that Yang-Yang might understand, if the adults could see what is in front of the children, they might see what is behind their own view.

NJ is completely blind to the fact that his daughter, Ting-Ting, is struggling through her own relationship problems, trying to win the affections of someone she has a crush on. The outcome of that relationship (which I will not spoil in this review) is similar to what happened with NJ and a girl that he dated when he was much younger. We see through Ting-Ting what NJ’s childhood girlfriend felt, and when she enters his life again later, NJ is again blinded by the past.

Yang-Yang takes his idea of being half blind further. He takes photographs of the back of people’s heads, thinking that he is helping them by showing them the whole truth. When he encounters one lady that he can tell is sad, he stares at her. When questioned, he says, “I wanted to know why she’s unhappy. I couldn’t see from behind.” To the viewer, Yang-Yang’s curiosity is a part of his cuteness. He is an adorable little boy, and this is one of those funny fixations that children can get. It is humorous to see what length children will go to understand the world they are growing into.

While it is easy for Yang-Yang to be curious, it is difficult for the adults to look back and come to terms with mistakes they have made, much less try to rectify them. One character takes a journey to try to make up for his actions decades ago, the same issues that his daughter is experiencing at that very moment, but this is an exercise in futility. This is yet another example of how he can only see half the truth, and if he goes trying to find the real truth, it is not something he can change or undo. It truly is behind him. The only thing he can change is what he can see.

Edward Yang was quite the filmmaker, and he made a deep and beautiful film. There are many other characters, motifs, and elements that I could explore – such as the nature of business, luck, integrity – but at the heart of it all is family. Yang takes these experiences, personality quirks, and cuts them together so that we can see the correlations. While there are similarities within the families, everyone is different and must make their own decisions. The question is whether they will learn from or regret those decisions.

Yang does a good job at taking his time and pausing when needed. Some of my favorite scenes are when no action takes place, but instead there is quiet contemplation, usually with some music and gorgeous scenery. While there are some somber moments, he also shows the good times. Life is full of highs and lows, and we meet people we are compatible with, whether in a romantic relationship or business friendships, but things do not always turn out the way we want.

Yi Yi, simply put, is about the cycle of life. We are curious when young, but will make mistakes as we get older. Hopefully we will learn to live with these mistakes, have some good times along the way, and achieve a sense of peace. Yi Yi is life.

Film Rating: 10/10

Supplements

Commentary: Edward Yang and Tony Rayns in conversation.

Wu, who plays NJ, was a screenwriter that worked with Yang and had not acted, but Yang recognized his talent as an actor. He is a very celebrated and busy writer.

They used the coma was a device to get into each character, but it is scientifically proven that speaking to someone in a coma does achieve some results although the grandmother had one of the deepest and most dangerous comas.

There were a lot of informational tidbits about modern society. For example, they used a subway system news item to date the film; trains were used for nostalgic reasons; the government was well known to be involved with criminals and it was intentional to come out in the film, and the American presence is very obvious in Taiwan. I didn’t write down as many tidbits while watching because it is long, and because I got carried away in the film and the commentary. It was an enjoyable conversation with Rayns asking Yang questions about the film.

Tony Rayns: He talks about the history of Taiwanese film. Started in 1950s because it had been Japanese colony. The nationalist government settled there and used film as propaganda tool. It was used by Chinese to inject their cultural identity.

Even though there were young filmmakers, there was nothing like a New Wave in Taiwan. Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang collaborated with Taipai Story, and the pair generally led the film movement. Much of their work was intentionally higher quality in opposition of some of the poorly constructed older genre films.

Yang is more intellectual and has complicated plots. His many characters add up to a broader picture. Surprisingly, Yi Yi has not been screened in Taiwan. Most of these minds split up for whatever reason and film business in Taiwan is “effectively dead.” They cannot compete with American films.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

Episode 4: Day for Night and François Truffaut 1968-1975

Or listen here to it here:

For other apps or mobile devices, try this link.

Or direct download/listen to the MP3.

Show Notes

Episode Outline:

0:00 – Welcome, Introduction, Corrections.

12:15 – News

34:25 – Day for Night

1:19:05 – François Truffaut 1968-1975

My Life as a Dog review

My Life as a Troll – My take on the trolling

On Spoilers and Trolls – MoviesSilently came to my defense.

Corrections

How I Won the War

Badlands

Black Girl and A Touch of Zen at NYFF

The Last Temptation of Christ – Pop Culture Pundit

News

Latest Wacky Drawing – Gilda? Red Beard? Hedwig?

Documentary Now: Kunuk Uncovered

Zatoichi – one day sale at Amazon. The sale was last week, and is now back to regular price.

Day for Night

François Truffaut – 1968-1975

Where to find us:

Mark Hurne: Twitter

Aaron West: Twitter | Blog

Criterion Close-Up: Twitter | Email

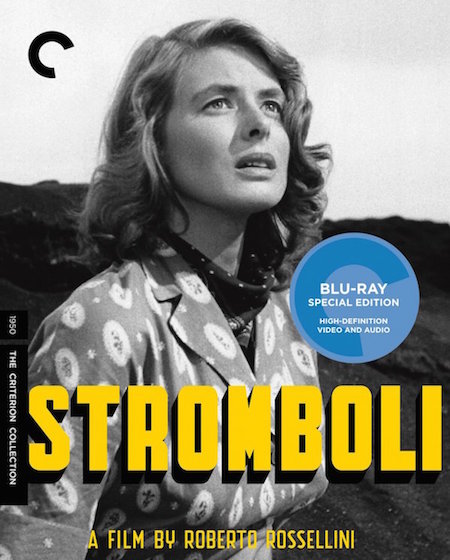

Stromboli, 1950, Roberto Rosselini

It is fitting that I am writing this post to celebrate Ingrid Bergman’s 100th birthday for the Wonderful World of Cinema’s Ingrid Bergman Blogathon. I haven’t counted the Ingrid Bergman films I’ve seen. Perhaps it is a dozen, perhaps two, but few portray her anywhere close to the strong, resilient female character as she is in Stromboli. There are many other co-stars, including two prominent male characters, but this is undoubtedly Ingrid’s film. Not only does she represent a strong woman, but she comes to representing all strong women and the battles they must fight in a male-dominated world. In this regard, I see Stromboli as a staunchly feminist statement, which is ironic given that it is the first collaboration between her and future husband, Roberto Rosselini.

Bergman plays Karen, who we initially meet in a prisoner camp. One of the first actions she takes is to marry an Italian in order to escape the camp. Was this a marriage borne of love? Quite the contrary. It was a marriage for self-preservation and survival. In the wedding scene, the sense of apprehension is clear. Even in the above image, we can see the husband looking stern, and the wife looking distracted by her thoughts, looking off to the side. She is not marrying out of love and is nervous of this new direction in her life, but it is something that has to be done in order for her to persevere.

Her husband, Antonio (Mario Vitale), comes from the island of Stromboli off the coast of Sicily. He promises her paradise in exchange for her hand in marriage. What she finds upon her arrival is anything but. She is subjected to a barren, empty life. She finds that many of those who live in island have left for America or elsewhere, but many have come back. When asked why she returned from America, Antonio’s mother answers, “this is my home.” Karen’s home is in Lithuania, far from the Sicilian shores. This place is unquestionably not her home, nor does she want it to be.

Much of the film consists of Karen walking around the island, exploring not only her surroundings, but also herself. Bergman, always a fantastic actress, does a tremendous job at emoting even when she is not speaking. Her face betrays her anguish and inner torment as she quickly finds herself in despair, practically alone in this island. The only instance that lifts her spirits is when she encounters another man, who is almost the opposite of her husband. She beams and smiles in his presence. It is not clear whether she has romantic intentions with this stranger, but this man is a far better match than her husband. Regardless of whether her intentions are pure, the locals indict and reject her, as does her husband.

Please be warned that after these two images that contrast Karen’t anguish and happiness, there are minor spoilers and I will discuss the ending.

The violent nature of the island and its inhabitants is communicated through the way people interact with the elements. The locals see the local animals as their prey, and they treat them with cruelty. There is one difficult scene for animal lovers with a rabbit, which horrifies Karen. The men have to fish to live, and in fact, Antonio and Karen’s livelihood depends on his being successful with his fishing ventures. What follows, which Karen witnesses, is a violent slaughter of tuna. Both of these are among the most jarring scenes of the film, yet they are also the most effective. This violence also signifies a moment of final realization for Karen. If at first she was just wary and uncomfortable, she is now horrified. These are not her people in any respect.

The volcano is the most violent aspect of the island, and it also parallels the story and Karen’s journey. As she reaches the island and finds herself not fitting in, you could say that she is disturbed and rumbling. After she sees the slaughter of the fish and rabbit, the rumbling becomes an eruption of the volcano, but it is also Karen’t eruption. She does not act up, and she does not need to. The volcano scares the locals, who try to escape it by evacuating on boats.

Karen is not stirred by the volcano, but instead magnetically drawn to it. In a memorable final sequence, she decides to finally rid herself of this horrendous place by bravely climbing to the top of the volcano. It is in this sense that I see Stromboli as a feminist journey. She was oppressed by the world of man twice. The first time was in a actual prison while the second might as well have been a prison. Rather than succumb and subjugate herself to this tyranny, she frees herself by conquering an erupting volcano. This volcano that she defeats represents the world of man. The final sequence with Karen on top of the mountain is magnificence. It represents hope, salvation, not just for Karen, but for women in general.

Film Rating: 9.5

Supplements

Introduction by Roberto Rosselini:

This is a short two-minute introduction. He says it is about someone who survived the war and learned survival instincts, yet finds herself trapped.

Adriano Aprà: 2011 Criterion interview with film critic.

This project was scandalous because Bergman was married and Rosselini had a mate (Anna Magnani). A love affair began and they were invaded by tabloids and journalists. It was also a scandal that he “stole” an American star to make an art film. The film stands apart from the gossip that surrounded it.

What’ I found interesting is that she didn’t care for the films she did with Rosselini, and only liked one of her collaborations (Joan of Arc at the Stake). We find out later from her memoirs that she was surprised when they were re-discovered.

Rosselini Under the Volcano: 1998 documentary.

These are the types of features that I adore. They revisit the island all these years later to see what is left. They show the volcano erupting. Back when the film was shot, the volcano erupted continuously, every seven minutes on the dot.

They interview the little boy that Bergman speaks to, of course now fully grown and having aged a bit. The two male leads meet. Mario talks about having to have the English words written for him phonetically because he did not speak a word.

A sad story from the production is that one person passed away during the production. A general helped lead them to the top of the mountain, but inhaled some poisonous gas along the way and had to be taken down to the base. He later died.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

Top 20 of 1997

The late 1990s were a period of transition. The indie movement was running its course. Instead we had a new brand of auteurs, both American and international, making their mark and establishing themselves. Paul Thomas Anderson was getting rolling with Boogie Nights, as was David Fincher, further distancing himself from being a music video director. Abbas Kiarastomi, Hayao Miyazaki and Takeshi Kitano were in their prime, while newcomer Michael Haneke showed some promise with a caustic take on the thriller genre. We would hear a lot more from him. Atom Egoyan and Quentin Tarantino were the main holdouts from the indie era. The former’s career would take a nosedive after this high point, at least in my opinion. QT is still hanging around.

I recently wrote a piece for Kiarostami’s Where is my Friend’s House? over at Wonders in the Dark, but I used Taste of Cherry as a point of comparison. If you have seen both films, you can see the parallels. Many will see it as a film about an older man driving around on dirt roads, but it is much deeper than that, and is a remarkable achievement in filmmaking.

There are a couple of guilty pleasures. Contact stands out, but part of that is because I’ve been an astronomy junkie and read the book when I was younger. I found it fascinating how it mixed real science in with the narrative. Most of that is thanks to the late Dr. Sagan. Starship Troopers could be considered a guilty pleasure, but I truly feel it is unfairly maligned. Flixwise had a good discussion on the subject. I feel that number 20 is low, but this turned out to be a good year for film.

Other late cuts were comedies like Grosse Point Blank, Wag the Dog, and Fierce Creatures. David Lynch’s Lost Highway was in the mix, and I think it could in the mix after a rewatch (Criterion?). The other two that I hated cutting were Donnie Brasco and the brilliant documentary, Waco: The Rules of Engagement.

1. Taste of Cherry

2. The Sweet Hereafter

3. The Ice Storm

4. Boogie Nights

5. Princess Mononoke

6. Insomnia

7. Funny Games

8. L.A. Confidential

9. The Game

10. Cure

11. In the Company of Men

12. Perfect Blue

13. Jackie Brown

14. Little Dieter Needs to Fly

15. Hana Bi

16. Gattaca

17. Fast, Cheap & Out of Control

18. Contact

19. Open Your Eyes

20. Starship Troopers