Category Archives: Film

My Life as a Troll

This morning I posted a review about Lasse Hallström’s My Life as a Dog over at Wonders in the Dark. Some may remember that I podcasted it with Martin Kessler a couple weeks back, and my review basically touched on the analysis that we talked through. I was pleased with the piece, and went out of my way to avoid major plot developments. I did speak generally as to the problems that Ingemar faced and how he handled them. I let it go and figured I would get a good response.

Instead I got trolled. I’ve been trolled before. That’s unavoidable in the modern day of anonymous commenting. Even this site has been trolled. Actually a good friend of mine was trolled just recently and I defended him. Trolling is something that has to be accepted, and I agree with the wise advice that trolls should not be fed. In a moment of weakness, I fed this troll. I defended myself, and that prompted the troll to continue.

The subject was not about the quality of the review. This person actually complimented that. The problem was with spoilers. In speaking of the film, I revealed a couple of minor developments although I did not reveal the major, traumatic plot points. I’ve written about a lot of films and have learned ways to navigate around them, in the hopes that if someone has not seen the film, they won’t be spoiled. On the other hand, those who have seen the film know where I’m getting at. Some people are spoiler sensitive, and so I developed a Spoiler policy a long time ago, which you can see on the About page. When talking about a newer film, I’ll be careful to warn people of spoilers. If I don’t have to spoil a film, i won’t. Sometimes the ending is required to delve deep into an important film, and what I’ve done here is separate it with a warning and an image. People can keep reading at their own risk.

This person pointed out what I spoiled. One specific was how I defined a major character. What I said is something that is revealed within minutes of this character’s introduction. The other had to do with him parting company with someone, which happens very early in the film. Now some of these plot points do come back into play later in the film. I stand by the fact that I did not spoil the film, and Martin and I were careful in our discussion to do the same.

Have I ever mentioned how much I love the internet and social media? First off, some of the regular commenters rallied to my cause. I highly recommend you read the comments, although be warned, we spoil under-seen films such as Star Wars, The Sixth Sense, Psycho, Casablanca, and others. The commentary became very funny, and it extended to Twitter. I have to give a shout to Fritzi from Movies Silently for giving me a few chuckles. I was not the only one chucking:

And with good reason:

This troll also mentioned that we should write more in the TV guide style. Fritzi called her bluff:

It is easy to have fun with the subject. The troll probably has taken offense, and has back-tracked in the thread, but I will concede that spoilers are something to steer clear of. If I’m watching something that’s obscure and people probably haven’t seen before, then I’m not going to ruin it for them, but instead use my words to tantalize them. On the other hand, modern, professional film writing requires that you talk about all aspects of a film. I know that, and that is why I avoid reviews for films I have not seen.

There’s also the point that people can be too spoiler sensitive. I understand and appreciate that people like to go into a film clean, and I am one of those people with new films. If something is spoiled, I don’t make a fuss about it. I’ve had major films spoiled in film studies classes. It would be unbecoming to raise my hand and troll my teacher. Life is short. Movies are fun. Don’t worry about little things.

So what did I learn from this?

A) Do not feed trolls.

B) The internet is funny.

C) Probably should be careful with spoilers.

D) There is a hidden oasis of TV-Guide reviews hiding in some dark corner of the internet.

Criterion Close-Up 2: My Life as a Dog & Lasse Hallström’s Career

Or listen here to it here:

For other apps or mobile devices, try this link.

Or direct download/listen to the MP3.

Timeline:

0:00 – Intro: Introductions, Housekeeping, Criterion News.

25:00 – My Life as a Dog discussion

1:00 – Lasse Hallström discussion

Thanks to guest host Martin Kessler for joining us.

New show Twitter: CriteronCU

Wish list:

The New World

Clouds of Sils Maria (DVD release already out)

La Chienne

News:

Wim Wenders Janus Retrospective

Late Spring Criterion has Tokyo-Ga.

Arrow’s The Jacques Rivette Collection (Region B only)

Imamura Masterpiece Collection (Region B only)

My Life as a Dog

Film Rating:

Mark – 7.8

Aaron – 7.5

Martin – 8

Average: 7.76 (rounding up to 8)

Criterion Rating:

Mark – 7

Aaron – 7

Martin – N/A (sorry Martin, forgot to get yours)

Average : 7

Lasse Hallström

What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?

The Cider House Rules

Chocolat

The Shipping News

Auteur Rating:

4/10 (sorry Lasse)

Where to Find Us

Martin on Twitter

Aaron on Twitter

Mark on Twitter

Criteron Close-Up on Twitter

Flixwise

Criterion Blues

Criterion Blues on Facebook

The Ice Storm, 1997, Ang Lee

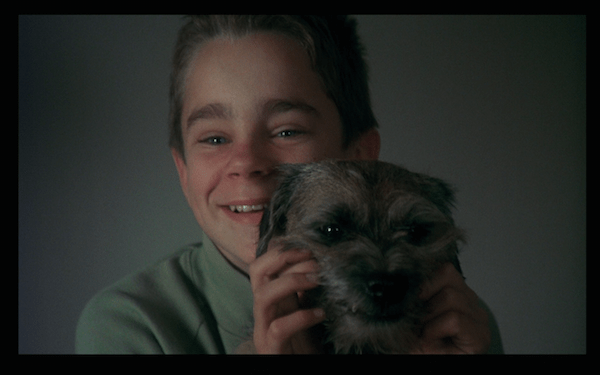

Some films are so thematically rich that it’s nearly impossible finding an angle. There are just too many options. The Ice Storm is one such film. I could look at it from the period, the unruliness and political instability of 1973. It could be seen as a grim portrait of despicable and irresponsible people. Instead, I chose to approach this as a contrast between the sexual behaviors and confusion of children versus their parents.

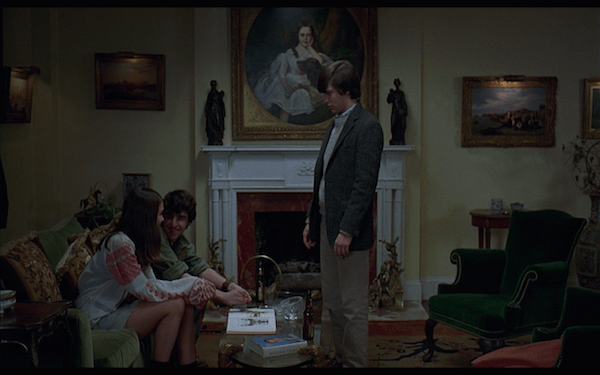

With such a large ensemble cast, a great many character parallels can be drawn between the familial bonds. There are two primary families of characters, the Hoods and the Carvers, with no real single protagonist. A good argument could be made for many of the characters as the primary protagonist. Ben Hood (Kevin Kline) gets a lot of screen time and his actions initiate much of the plot. The narrator is his son Paul (Tobey Maguire), although he plays a comparatively small role. Elena Hood (Joan Allen) is also a central figure, as is their daughter, Wendy (Christina Ricci). The Carvers are important but secondary characters. Janey (Sigourney Weaver) is in some respects an antagonist, yet she has a few sympathetic moments – primarily with parenting. Her husband Jim (Jamey Sheridan) is a passive character, as is his son Mikey (Elijah Wood), but not the other son, Sandy (Adam Hann-Byrd).

Ben is a terrible parent, terrible husband, terrible adulterer, and completely unaware of all of this. He is living in another world. The fact that he’s having an affair with the icy Janey is surprising. He doesn’t seem like the type of paramour that she would settle with, and the attraction is waning. “Ben, you’re boring me. I have a husband. I don’t particularly feel the need for another,” she tells him after he goes on about his problems. He is more hurt by her rejection than by his wife’s suffering as a result of the affair. His lack of awareness extends to his terrible excuses, which his wife rightly sees directly through.

Ben is at his worst when he tries to be a father. There are two instances where he comes off as a buffoon while parenting about sexual matters. One instance is when he talks to his son Paul about masturbation while they are driving in the car. He tells his son not to do it in the shower because it is a waste of water, and everyone knows what he is doing anyway. Paul looks befuddled, unable to respond. What can he really say? What if he does not masturbate in the shower? What if he does? He is helpless at discussing the situation, and it really is not a discussion anyway. It is an awkward diatribe from a sexually confused father. When they arrive at the house, in a brief moment of self-awareness, Ben asks, “Can you do me a favor and pretend I never said any of that?” Of course he cannot, but he is not about to bring it up again.

In another instance, he catches his daughter in a promiscuous act with Mikey Carver, and he gives another silly diatribe towards them. Again, it is awkward. He is terrible at it, not understanding the situation and accusing Mikey of going further than they were. What made it more ridiculous was that his daughter, Wendy, was wearing a Richard Nixon mask. The conflict ends with her being rebellious, saying “and forget all the stern dad stuff.” This is not the first time she has lashed out at him. At one point she calls him a fascist, and while he challenges her on it, she seems to understand the world better than he does. She is curious about life, but more comfortable and deliberate, and immeasurably more expressive and compassionate.

Elena Hood (Jane Allen) is one of the more fascinating characters. Knowing that her husband is cheating on her, she takes refuge in trying to live vicariously through her young daughter. She fondly remembers the feeling of being free, which is probably an idealized and unrealistic memory. She sees her daughter riding her bike down the road, merely using it as a means of transportation to one of her romantic trysts. Elena sees the act of riding the bike and letting the wind blow in her hair as liberating, yet she is not sexualized like her daughter and you wonder whether she ever was. She rejects the advances of a progressive, freethinking pastor, who uses religion as a way of “breaking the ice” with a frustrated, married woman. It is not until the real ice storm begins where the sexual tension reaches a breaking point for all of the characters.

This was my second viewing of The Ice Storm, and before the first, I had never heard of a Key Party before. It is where everyone drops their keys in a container, and later the ladies draw them one by one. Whichever man’s key is chosen goes home with the lucky (?) lady. It is a foolish game, so silly that the youngsters would not even consider it. With a number of married or dating couples, one of whom has a boyfriend young enough to be her son, there is going to be unpleasantness and jealousy. Adult or child, it is a terrible idea. The outcome of the key party is a spoiler, so I won’t share it, but it is yet another example of how conflicted the adults are sexually.

The children are curious and spend a lot of time exploring the opposite sex. Wendy is romantically assertive, while all of the other characters are passive. Paul shares some of his father’s bone-headedness, as he pursues Libbets Casey (Katie Holmes) who is not only out of his league, but shares more in common with Janey than anyone else in the film. She begins the film with an icy reaction to Paul’s advances, and is ambivalent to him at their little private party even though he does not fit in. Like with another romantic tryst, alcohol is the catalyst, but Paul’s connection with Libbets is just as pathetic as any of his father’s activities.

Mikey is as lost as his father, Jim. Again, I won’t spoil the film, but things happen to them due to their being detached from the world, and in the finale, they express that detachment is specific and different ways. Jim is basically a non-entity, while Mikey is more interested in molecules than with catching a football.

As I alluded to at the beginning of this essay, The Ice Storm is deep, as it is convoluted. It is also extremely well put together, has some terrific performances. Joan Allen and Christina Ricci really shine. It also has some phenomenal shots and motifs. The ice is the most impressive, both as a plot device, a character descriptor, and as an example of gorgeous set design. After seeing the film twice, I’ve found that there’s a lot more depth than merely frozen water.

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements

Commentary: 2007 with Ang Lee and James Schamus.

They introduce the film as the lowest market research tested film he’s ever done. That makes sense to me since it was marketed as a mainstream indie, but is dark and intricate. I would not expect it to test well at malls.

Lee says “F You” to Schamus in opening credits, and we can tell that they have a jovial and tight relationship. Schamus knows what questions Lee gets asked and which ones annoy him.

Schamus says that this is not a faithful adaptation of 1973, but it is an adaptation of what people remember about 1973. Everyone worked together to “craft this memory landscape.”

The book was structurally difficult to adapt. They had to “open it up” as Schamus said, which they did by showing all the characters at the beginning and ending. Lee calls it a “circular structure.”

Weathering the Storm: 2007 documentary.

There were a number of interviews with the cast, some of which were better than others. There were many statements of “it was an honor working with … “ someone, which are common in these type of featurettes.

There is plenty of discussion of the “adults” versus the “kids” and how they interacted. Older actors watched out for them and used them for inspiration, while the younger actors were intimidated at first and then warmed to them.

One of the most interesting parts of this documentary was with the kids talking about sexual encounters, which was weird for them. One of the best quotes comes from Elijah, talking about how he was coming to terms with sexuality personally, so he has to come to terms with it in the film too.

They are all proud of the film, even if it didn’t do well.

Rick Moody Interview: 2007 interview with the author.

He talks about the feeling of handing off his work over to someone else. It feels like giving some part of himself away. His book was first person, whereas the film was third person, yet there are examples of first person narration in film, primarily through Tobey Maguire (although having not read the novel, I am not sure whether that character is the narrator).

The town was actually the town that he grew up in, and the town wanted to impede the shoot because of the subject material. That was strange for him.

Lee and Schamus: 2007 Conversation at Museum of the Moving Image.

I tend to enjoy these podium conversations, because they are usually not artificial. Often they are asked good questions.

This was filmed after Lust, Caution, which is probably safe to say will not come to Criterion. They talk about his career trajectory, being repressed in his homeland and getting an opportunity when he came in touch with Schamus. Lee gave a bad pitch, but he described a movie he had already made in his mind, and that vision impressed Schamus. The relationship has worked well for both of them.

Lee calls The Ice Storm the most artistic film he had done. I wonder if he would say the same thing now that Life of Pi exists. My personal observation when perusing his career is that he does a phenomenal job of adapting others, including this film and with Pi.

The Look of the Ice Storm: Interviews with three of the key visual artists behind the film.

Frederick Elmes – Cinematographer

They found photorealist painters from early 1970s and used them to develop style and natural light. This was filmed intentionally late in the season, so little warmth outside, but there was warmth inside. They made a strict distinction between Janey’s and Klein’s house – warm versus cold.

Mark Friedberg – Production Designer

It was the first story he worked on that he didn’t have to research. He lived it. His dad was an architect, so he knew the styles. He was not prepared for the ice. It turned out that was a challenge. It had not been done before. He used unusual tooks like hair gel, which was effective, as it looked frozen. The biggest challenge was the large frames. Glue was used a lot for the wide ice-work.

Carol Oditz – Costume design

She lived in the period and still had to research. She looked through vintage stores, found 70s fabric, and did a lot of crocheting. The Kline family were in lighter tones, whereas Sigourney in murkier tones. That impacted the character differences. She said that Kline was “naughty” with costumes because it was not comfortably fitting like modern clothes. He did knee bends to loosen them up and they had to repair them.

Deleted Scenes

Often I find deleted scenes superfluous, and I would say that is true for the majority of the ones here. The one I wish would have made the final cut is the Reverend moving forward in trying to pick up Joan Allen’s character. I think it would have added dimension to her struggle. The other scenes were interesting, yet not essential.

Criterion Rating: 9.5

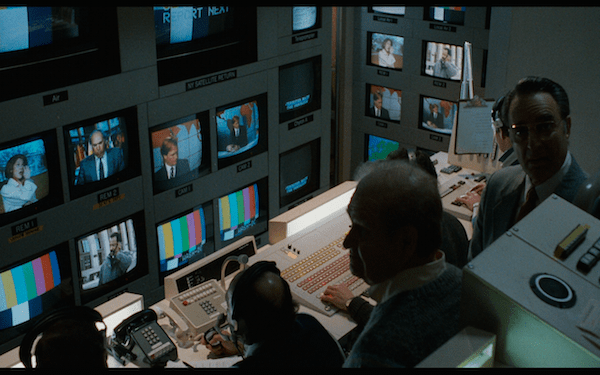

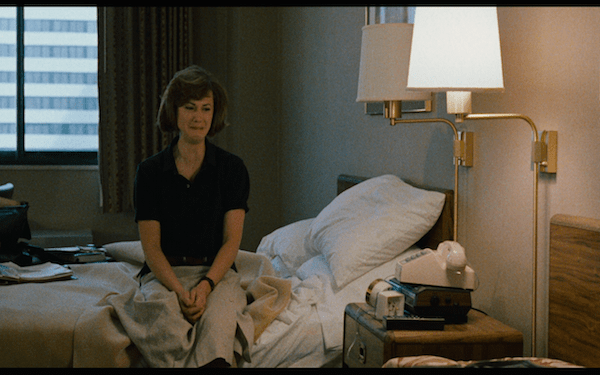

Episode 1: Broadcast News & Media through Film

SUBSCRIBE TO THE PODCAST HERE (Not all browsers are friendly with this link, but most mobile devices will be.)

Or listen here to it here:

Show Notes

Podcasts we love:

Criterion Cast

Eclipse Viewer

Wrong Reel

Flixwise

Filmspotting

First Time Watchers

InSession Film Cast

News

Dressed to Kill

The Graduate

Don’t Look Back

Where to find us?

Facebook

Podcast Directory

Aaron’s Twitter

Mark’s Twitter

Email us at Criterion Close-Up

Broadcast News

Film Rating:

Mark: 7.8

Aaron: 8.0

Combined: 7.9

Criterion Rating:

Mark: 9

Aaron: 8

Combined: 8.5

Media in Film

Positive Examples

All the President’s Men

The Parallax View

Good Night, and Good Luck

Shattered Glass

Negative Examples

Network

Nightcrawler

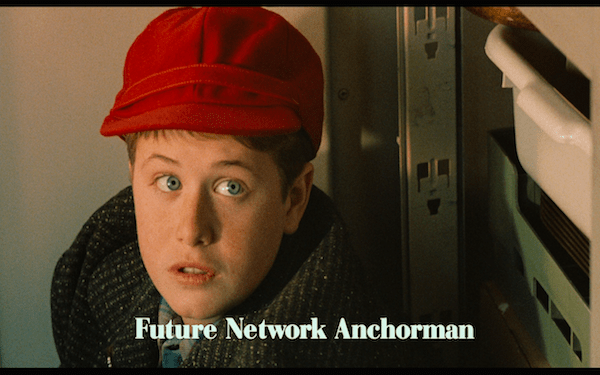

Satirical Examples

Anchorman

Being There

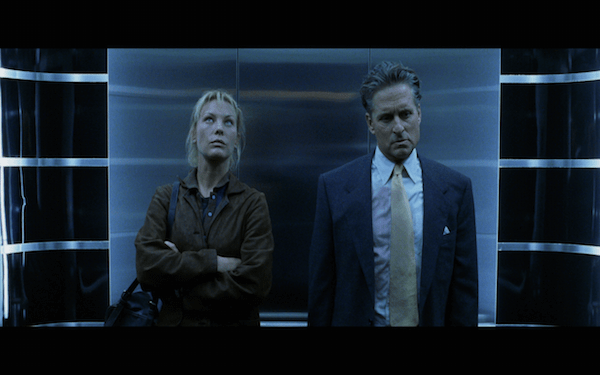

The Game, 1997, David Fincher

When did David Fincher become an auteur? Or is Fincher an auteur? He walks the tight-rope between thrilling, entertaining, telling a good story, and injecting a little bit of art into his canvas. He also has honed his craft to the point that you can expect solid filmmaking, regardless how accessible the film, with every project. I do not like every Fincher film. He still walks that tightrope. Gone Girl and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo are dense, twisty, psychological thrillers, whereas The Social Network was a well told story about The Facebook. I mean Facebook.

By the time The Game came out, Fincher had released two feature films, and the first, Alien³, barely counts. He followed that with Se7en, which, whether you like it or not, is firmly a step towards the auteur platform. I would (and will) argue that The Game was another big step, but Fight Club, the film after, cemented his status. Oh yeah, and he made music videos for Madonna, George Michael and others, which has proven to be a decent launching pad to auteurism (Spike Jonze, Jonathan Glazer, Mark Romanek, and others).

As Michael Douglas was being justifiably paranoid while running around at night in San Francisco, in my opinion, David Fincher was becoming an auteur. Many would consider Se7en a better film (not me). It was certainly daring to play with convention and dip his toes into experimental waters with the murder mystery, but I don’t think he had found his visual craft just yet. He most certainly finds this with The Game, and while I don’t think it his best movie, it is some of his best visual filmmaking and storytelling this side of Zodiac and The Social Network. This gave him the confidence to mess with people on Fight Club. He eventually would even make a movie about a dude that ages backwards. In my book he’s a visual and creative auteur, although my podcast co-host disagrees because he does not write his own work, and instead chooses to adapt best-selling novels.

Michael Douglas puts in good work as Nicholas Van Orton, a wealthy corporate carnivore, the kind of guy who takes down businesses in order to line his own pockets. We’ve seen this type of character before, and I am pretty sure that Douglas’ casting and his previous performance as Gordon Gekko in Wall Street was not an accident. He is playing a variation on the character, and would nod his head enthusiastically during the “Greed is Good” speech. Part of what makes the convoluted plot so enthralling is that Van Orton’s wealth puts him so far above society, sometimes figuratively and others literally. He even treats those below him with contempt, whether it is a random waitress who spills wine on his expensive suit, or the founder of a company that failed to meet earnings per share expectations. Nicholas Van Orton is, simply, an A-hole.

Things change when his brother, played by Sean Penn in a smaller role, gives him a gift of a “game” put on by a company called CRS. “Call that number,” his brother says. “It’ll make your life fun.” Van Orton could use a little spice in his life. He turns 48, the same age at which his father died of suicide. His way of celebrating this accomplishment is eating a hamburger and a cupcake birthday dinner alone in his mansion.

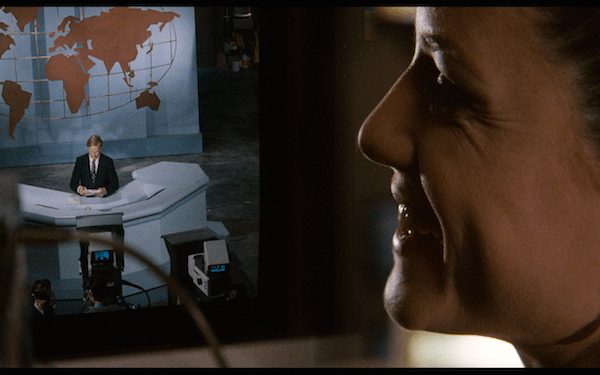

I will skip the nuances of the game, and just summarize it as an elaborate invasion of privacy that is paranoia inducing, genuinely demeaning and forces the participant to question every aspect of his life. His position of wealth is constantly at front and center during these adventures. It really begins when the TV reporter in the background stops reporting on the day’s financial news and speaks directly to Van Orton. The anchorman mentions some negative economic indicator, which Nicholas fails to even notice. All of a sudden, he is shaken when he hears, “but what does that mean to a bloated fat cat like you?”

As I mentioned above, I think Fincher established himself as a visual director. His images are sleek, polished, and framed impeccably. This is especially true with The Game which is filmed almost entirely under cover of darkness. It is not easy to make a dark film seem visually striking. They way he frames this dark world draws more attention to the presence of light, however minute. In some respects, you could describe this film as a neo-noir, as they are trying to unravel a mystery, but not a murder mystery. The continual shadows and silhouettes are an efficient use of filmic language to visually show the confusion and darkness that Nicholas is experiencing. He is lost in the movie and in his life.

One of my favorite scenes is when he returns home and finds it ransacked, decorated with black-lit graffiti while Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit plays loudly. What impressed me most about this scene is not just the visuals (although they are phenomenal), but how it directly addresses a theme that it has touched on throughout the film, specifically Nicholas’ relationship with his father.

In the opening scene, we see old home video footage of a birthday party. We see father and son pose together for a picture, and then the father symbolically walks away. As we learn in the film, he would end his life by throwing himself off a building. The White Rabbit scene addresses this theme with nearly sickening candor. On the wall is written, “don’t cry pretty boy,” and there is a note that says, “like my father before me, I choose eternal sleep.” Is CSR trying to push Nicholas towards following in his father’s footsteps and ending himself at the age of 48? Or is this is just a way of invading the topics that are the most personal and painful for Nicholas? These are many of the questions that we ask as Nicholas tries to uncover the truth behind CSR.

Some are critical of the ending, and I will admit that although I accept it, I am not thrilled with it. I will say that it partially invalidates some of the more interesting thematic questions that the film touches on, including the aforementioned daddy issues. Do not worry, I will not spoil it here, but I will explore a couple of the questions that I found interesting.

What does the film say about society and honesty? Nicholas is hardly a trusting individual, which is not only because he is playing his part in this game. He is also not trustworthy, and we see him lie or stab people in the back at business, which is probably an average day at work for Van Orton. During the game, whether he knows it or not, many people are lying to him, including many in which he places his trust. The fact that he offers some trust is a bit of character evolution, although it probably is temporary as it is out of self-preservation.

Michael Douglas is in virtually all of the scenes, yet the events of the game defy credibility even for a Hollywood film. One question I had was whether he was a reliable narrator. We learn that he has demons, personal issues, a lot of stress, and no real close friends. Could he be going crazy? Could this “game” be a way of him processing this psychosis? In one scene he finds a hotel room that has drugs and compromising, scandalous photos, but we know from the film that he was not in the hotel room. Could there be another Nicholas, an even seedier Nicholas, that is being hid?

I could go on, but I’d rather stay away from spoiler territory and leave it at that. I was pleasantly surprised by this re-visitation to find an accomplished and engaging thriller, one that was crafted with the care of someone who loves film.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Commentary: 1997 Criterion Collection with Fincher, Douglas, the writing and production crew.

This is not my favorite type of commentary because they transition from different people involved with the production, and the comments do not always correlate to the events as they are happening on screen. It is partial commentary and partial interviews about the film. The commentary is best when Fincher or Douglas speak.

Douglas: Some directors have a love/hate relationship with actors. They need them, but they resent them because of their salaries, etc. but that did not happen with Fincher and crew on this film.

When he could not open the briefcase in the office, Douglas impulsively acted violently towards the case. He thought the character called for that sort of outburst and Fincher liked it.

Christine tells him in the elevator that she is not wearing underwear. That’s a lie. There are other scenes that reveal that she is wearing underwear. She will say anything to get him to cede control, which is part of the CRS way. She is directing him within the game.

In the first draft, Van Orton was a nicer character. Most Hollywood films want a character people can sympathize with. It was Fincher that moved the character back into darker territory, which is a brave move.

The shooting schedule was 108 days and he was on the set for 107. They were very far out of continuity. The challenge was knowing where you were in the film, so he had to think about tempo.

Douglas really liked The Game. He thought it was well made. The only thing he questioned was whether it had heart and soul. The Game was measured ultimately on the box office (which seems okay from what I can tell, so I don’t understand his statement). He understands that people had trouble with the film, but it will have a long shelf life.

Alternate Ending:

I’m not going to reveal much here because I don’t want to spoil the real film, but I will say that this alternate (I believe) omits what could be seen as a familiar Hollywood trope, so I most likely would have preferred it.

Film to Storyboard Comparisons:

They show the dog chase, taxi scene, Christine’s house, and the fall.

These were fun to watch, if not revelatory. They just show a large part of the production, while also showing some of the director and photographer’s vision as they translate the storyboards into shots.

Behind the Scenes:

These also covered many of the same storyboard scenes. I will not go into them one by one, but these were interesting as a glimpse into the trickery behind how they created effects. I always enjoy seeing the scene, especially some of the more complex scenes in this film, without the movie magic. I came away from these scenes more impressed with Douglas as an actor. In fact, I’d say I came away from this film impressed with Douglas.

Psychological Test Film:

This is really a deleted scene. It is the test film that Van Orton had to see during his CRS profile. It is cut like an experimental music video. Only portions of it made it into the finished film. Again, not essential, but a little bit of fun.

Criterion Rating: 8.5

Top 20 of 2007

Again, I like a little bit of time between lists because over time films that were not buzzed about will get discovered, and some films settle better over time. I liked my top three initially, but I also liked other movies initially that have worn some. Ratatouille and Knocked Up are two such examples. They are good films, but do not have the replay value of the top three, all of which I have seen at least once.

There are three Criterion films on this list, and I saw all of them for the first time this year. There is one other Criterion 2007 release that did not make my list, and that is The Darjeeling Limited. It is my least favorite Wes Anderson, but I was going to try to revisit for this poll and keep an open mind. For whatever reason (and honestly, a big one was lack of motivation), I did not get back to Wes. Another time.

There are five international films, which seems small. A Girl Cut in Two is a late Chabrol that I seem to be in the minority about. Although I don’t think many in the states have seen it. Funny Games was an American remake of an international film by the same director, which is quite unusual. What’s a coincidence is that the original film came out 10 years earlier, and spoiler alert, it will make my upcoming 1997 list. There is a similar scenario, albeit not identical, where an adaptation and the original will make two lists, but I won’t say which that is yet. Some will probably guess.

There are three documentaries on the list, although I’m not sure that the Guy Maddin film really counts. No End in Sight is a movie that was impactful at the time, but may seem dated now. I have not rewatched it, so there’s no way to know. Another highly regarded documentary, Taxi to the Dark Side did not hold up and did not make the list.

Finally, this is the first time that I’ve had a list entry directed by someone who follows me on Twitter. That would be Larry Blamire and Trail of the Screaming Forehead. The fact that he follows me had no influence on the film’s inclusion. To my surprise, it only has a 5.9 rating on IMDB (granted, that isn’t the ultimate arbiter). I think most do not get his humor or his aesthetic.

1. There Will Be Blood

2. Persepolis

3. No Country for Old Men

4. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

5. Secret of the Grain aka Couscous

6. I’m Not There

7. My Winnipeg

8. Zodiac

9. No End in Sight

10. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford

11. Secret Sunshine

12. Into the Wild

13. King of Kong

14. Control

15. Trail of the Screaming Forehead

16. Superbad

17. A Girl Cut in Two

18. Michael Clayton

19. Hot Fuzz

20. Funny Games

Introducing: Criterion Close-Up

Welcome to Criterion Close-Up with Aaron West and Mark Hurne.

It is hard to believe that the day has almost come, but we have decided to launch the podcast earlier than expected. We did a test run over the weekend on The Rose, which is actually going to be implemented into our second episode. Even though it was a rough run, we felt it was good enough to get started.

We’ve been working hard behind the scenes. You may remember from the prior post that we were undecided about the name. The majority voted for “Criterion Collective,” which we liked very much, but that was too close to Moisés Chiullan’s “Criterion Collected,” which was on hiatus, but I am told is coming back soon (and I am looking forward to it!).

We have an August schedule already posted over on the Podcast page. Keep an eye there as we’ll be posting archived episodes, upcoming episodes, and films that we plan on covering soon. This month we’ll have a “Criterion Close-Up” episode, which will be a regular monthly episode where we do not talk about a specific film. Instead we’ll talk about the recent releases, and usually some other related topics.

This coming episode is on Broadcast News, but it is on much more than that. We want to go beyond the film with our casts. We’re going to look at the film in-depth, plus we are also going to look into other films from the 70s up through today where the news media is portrayed, sometimes positively, sometimes negatively. Other films that we’ll be talking about will be Network, All the President’s Men, Good Night & Good Luck, Nightcrawler, and yes, even Anchorman, in addition to a few more. We think it is a ripe discussion topic and we expect a quality episode for our debut.

The episode should post early next week. We will be on iTunes, Stitcher, and probably other places, but that might not happen right away. Check under the Podcast section, or follow the Podcast category

While this first month will just be Mark and myself, we do have some fascinating special guests coming around the corner. We’ve already lined some up in September and October, and the list of people who want to be involved is long.

We hope you enjoy!

The Fisher King, 1991, Terry Gilliam

When I first heard about the release of The Fisher King, I wondered how many times I had seen it already. Even though it had been some time since my last viewing, there were too many to count. This just seemed to be the film that frequently came into my life, either on cable or video, or with friends. It’s an easily delightful and digestible film. As I began watching this new Criterion edition, I found that I practically knew every twist and turn, yet I still enjoyed it close to as much as the first time.

There are some films that are dense and reveal more with every revisit. Good examples of recent films I’ve explored are Black Narcissus and The Great Beauty. They have a level of sophistication, density, and depth that I’ve taken something new with every viewing (and for the Sorrentino, it took three for me to engage).

The Fisher King is not one of those films. That’s not to say that it is not sophisticated or artistic. It is quite an accomplished film, but the themes are overt and easy to pick up on, especially for a Gilliam film. Sometimes that is refreshing. It is not shallow by any stretch, but in a way it is like art-film version of comfort food. You can appreciate it without having to deconstruct and dissect it.

I’m not a fan of lazily using film mash-ups to describe a film, but it is tempting to do it here. For example, I could say that it is The Holy Grail meets My Man Godfrey meets Sleepless in Seattle. The reason is because the film is such a genre mash-up, and again, that contributes to the charm. It has the Gilliam-esque creativity, although somewhat muted, with a positive portrayal of the values of homelessness (and by extension, anti-commercialism) in New York City. Part of the appeal is that it effectively weaves itself between fantasy, comedy, drama, and gives an important life lesson without relying on over manipulation.

The man faces of Robin Williams from THE FISHER KING. http://t.co/C48c5zyRa9—

Aaron West (@awest505) July 28, 2015

In a way it hurts to watch The Fisher King today, because it was the quintessential Robin Williams role and his passing was tragic. Some of the highs, lows and demons of his character, Parry, may have been closer to Williams’ reality.

This was when he was in the midst of a transformation from a strictly silly actor into a serious actor. He eventually became a little of both. I always found him to be a funny man, but I gained a lot of respect for him as a dramatic actor. By this time, he had already turned in two strong performances in Awakenings and Dead Poet’s Society. Later in his career he would put in good work in films such as One Hour Photo and Insomnia. As much as I’ve enjoyed him as an actor, his turn in The Fisher King is my favorite, and is a character that few other than Williams could have pulled off. It is part zany and he often is very funny, yet there is emotional trauma buried down deep, which he has to come to terms with. Meanwhile, he is an endearing character because of his values in life. Who can’t fall in love with the guy who strips in Central Park just because? We also see him as a genuine, hopeless romantic, the type that embodies the definition of chivalry. He is a crazy, disturbed, but ultimately benevolent knight in shining armor.

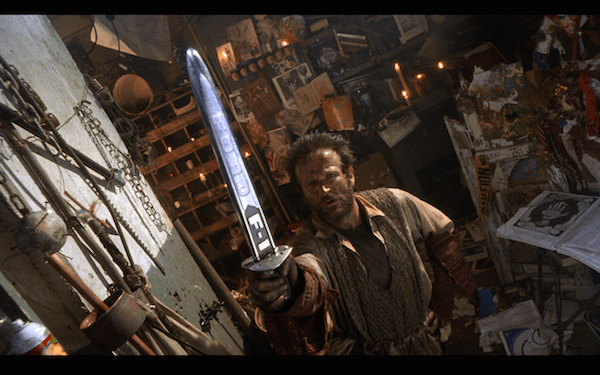

The Red Knight from THE FISHER KING. http://t.co/69x4QLCf19—

Aaron West (@awest505) July 28, 2015

This was also quite a departure for Terry Gilliam, but he left his indelible stamp on the film. Few could transform New York City into a convincing template for a fantasy world, but through his direction, it becomes wholly believable. The most impressive Gilliamism is the Red Knight, which is simply a beauty to see. We get to see an excellent, original creation that is used to represent a character’s persona. We understand Parry because of how menacing this Red Knight is portrayed. His demon is fierce and relentless, with a burning fire that represents wounds that have not healed.

The entire cast is extremely good. Jeff Bridges does a fine job at portraying Jack, the smarmy, better looking Howard Stern whose ambition and thirst for success is the anti-thesis of Parry’s ideology. His straight man performance complements Williams’ manic behavior. Plummer is also good playing Lydia, an odd, quirky and shy homebody. However, aside from Williams, Mercedes Ruehl as Anne steals a lot of her scenes. She is the dramatic center, the other side of the Parry coin that drives Jack towards his character evolution. She is the one that is devoted to him, the one he can count on, but even when he is learning about life through Parry, the one he continues to mislead and mistreat.

Speaking of stealing scenes, how can you not love Michael Jeter as a homeless man? He plays a flamboyantly gay man (or so we would assume). He is about as over-the-top as they come, but he is yet another facet into the appeal and the likability of the homeless crowd. His scene where he sings on behalf of Parry to Lydia in her office is not just a scene-stealer, but is one of the most memorable performances of the movie. That scene was a riot!

Again, even if not particularly deep, the film’s message on the trappings of materialism and selfishness are interesting. Through the great performances, creative directing, and originality maneuvering through a variety of genres, we have a movie that I can watch numerous times and still find joy in it years later.

Film Rating: 7.5

Supplements

Audio Commentary: 1991, Terry Gilliam.

- He had three rules when establishing himself as a director. 1) He would never direct someone else’s script, 2) for a major studio, 3) or in America. He broke all three with The Fisher King.

- He intended to portray Jack as completely unredeemable, a monster. People stuck with him simply because he was played by Jeff Bridges, a big star.

- The Pinocchio toy doll parallels Parry, who is going to become a real man during the course of the film.

- He thinks it is funny that the Holy Grail is associated with him. It was only in one film, and he thinks the association is overstated. In this film, the Grail is just a symbol for love.

- Jack is more of the character of The Fisher King because he has lost the ability to love. Parry still has that ability.

- His philosophy in film is to obtain the actor’s trust, make them comfortable and respect them. He realizes that other directors have taken advantage of actors and they don’t always have a great experience. A lot of directors probably say this, but the other cast interviews back up that Gilliam is truly an actor’s director.

- The violent scenes with him and the Red Knight were controversial in production. People tried to talk him out of it, thinking that the gore would be too much. He thought it would be fine and he was right.

Deleted Scenes:

I’m not always crazy about deleted scenes as extras on discs. That was the case here. The additions were minute and it is understandable why they were cut.

The Tale of the Fisher King – two 2015 documentaries with Terry Gilliam, writer Richard LaGravenese, producer Lynda Obst, Jeff Bridges, Amanda Plummer, Mercedes Ruehl.

The Fool and the Wounded King –

LaGravenese wanted to do something that was opposed to the cynicism that was prevalent at the time. They were also into the Holy Grail myth, and how people need a myth to love by. He wrote 4 different screenplays with the same two characters, and discovered Lydia in 2nd screenplay. Disney was involved and it was demoralizing. They basically wanted it re-written in a Disney style. They sold it to Tri-Star where it was assigned to “terrible directors.” James Cameron wanted to do it at one point, but he was in the middle of The Abyss. Tri-Star flew to London to talk Gilliam into doing something that went against his entire philosophy. He didn’t like to work with studios and liked independence and control.

People at Tri-Star had reservations about Terry Gilliam because of his last film, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, which was seen as a disaster from a studio’s perspective. Robin Williams worked with Terry on Munchausen, so they had a rapport. We’re all lucky he agreed to do it.

The Real and the Fantastical

Jeff was being casted against type. He had played mostly likable people before. Gilliam: “Robin was in awe of Jeff” and didn’t feel like he had to be funny and outrageous. Mercedes Ruehl’s character was based on an Italian-American video store owner that the writer knew. Terry loved Mercedes for this role.

Terry was great with the locations, arranging the big visuals. He was not great with the emotional tones of the actors, but he gave them the freedom to explore. He was great with the “Red Knight” stuff. He says that the idea came from a mixture between something in Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits and Grail legend. They were shooting in the rougher sections of New York, but Gilliam was creating a fantasy world.

Bridges talks about interacting with Robin, wondering whether he was going to be silly and take him out of the role. Robin was actually terrific to work with and would encourage him between takes, and would crack jokes only at the appropriate times. Bridges gets choked up when talking about this, probably thinking about how Robin had passed.

The Tale of the Red Knight – 2015 documentary with artists Keith Greco and Vincent Jefferds on making the knight.

They had to do create this being with real props and effects. There was no CGI or green screen back then.

They take out the props from the studio. They said, “do you want to work with Terry Gilliam”? They said yes without hesitation, and they had to get a helmet and other junk for him to look at as an audition of sorts. Terry said, “it’s all wrong, but you have the job.” They were always behind schedule because they were hired later. “It was like we were being chased by the Red Knight.”

They did the whole thing with a horse, a stunt guy with a lantern on his head, all painted red.

Jeff’s Tale: Images of the set from Jeff Bridges’ camera.

He takes these images on all of his films. He shows a number of production meetings, script meetings, and Mel Bourne often telling people there wasn’t enough money to do everything. He shows the various departments (sound, camera) on set and of course the actors. It is a fun supplement that gives a feel for what the production was like.

Jeff and Jack: Production footage of Bridges becoming Jack the radio shock jock.

Stephen Bridgewater was a shock jock that stopped radio and became an actor and director.

Bridges is a good fit. They show him doing the show. He talks to some women, tells them to take their clothes off, get some Wesson Oil, and then drink it. He calls a lady that had sex with a US senator. He speaks with an offended lesbian. “Congratulations,” he says. He does a variety of versions of calls that happen in the film, such as the person whose husband finishes sentences, which was as effective in the outtakes as it was in the final film.

Robin’s Tale: 2006 Interview with Robin Williams.

He said that New York City is a magical place, and it really seemed like it when shooting that film. Robin loved Gilliam: “He is the element that makes this work.” He credits everything to Gilliam and it is clear he is genuine. He also contrasted this project with Gilliam’s previous works by comparing it to a mural painter who is asked to paint a miniature.

Robin is goofy when telling anecdotes. He does voices and injects humor, like when talking about homeless people at the Red Knight scene, or talking about Jeff Bridges as a sex symbol. He gets serious when talking about his peers, like Ruehl, Plummer, and of course Gilliam. He gets very serious when discussing the intricacies and meaning of the film. This one meant a lot to him.

Costume Tests:

We see the entire cast trying out costumes to the “How About You?” theme song. It is a fun, short novelty.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

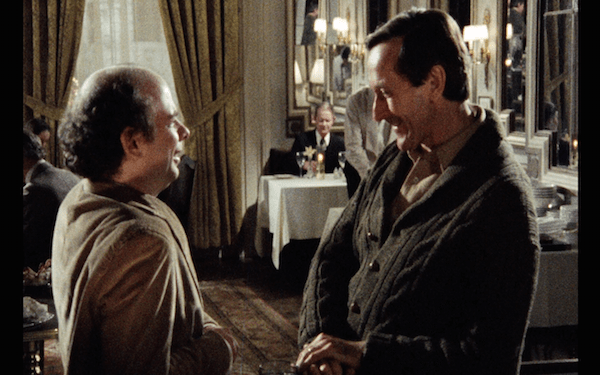

My Dinner With Andre, 1981, Louis Malle

My Dinner With Andre has been on my radar for decades now. It seems like yesterday that Siskel & Ebert wouldn’t stop raving about it. In film circles (and probably non-film circles too) it has become somewhat of a joke. It is respected as a piece of art, but it is known more as the movie where two guys sit in a restaurant and talk for two hours. It is often cited as that inaccessible art film that makes no sense as entertainment. I’m sure many people have asked, “why would you want to watch a movie where two people just talk to each other?”

Even though I often appreciate dialog-driven movies, I prefer some engagement. Eric Rohmer is a good example of someone who makes “talky” movies, but at least his films are character driven and have a distinct plot – usually a romance. How would the plot of My Dinner with Andre be described? Before seeing it, I would probably sum it up like David Blakeslee’s tweet the other day.

https://twitter.com/DavidBlakeslee/status/624700909226848257

I don’t want to steal David’s thunder. He has a blog over at Criterion Reflections where he tackles films chronologically by year. By the time he gets to 1981, I have a feeling he’ll have a little bit more to say.

Now that I’ve seen it, I would describe the plot as two friends meeting, one of whom is struggling to get his career going and the other having just emerged from a life-altering personal crisis. Their dinner conversation becomes a catharsis for both of them and they reach a new understanding about life and themselves. Even that is a simplification, but it’s a better description than most would give.

If not for this project, I may never have watched it, yet I’m glad that I did. As a warning, it is inaccessible, and it is a slog especially during the early going. However, once you get through the more arduous parts, it transforms into something special and is rewarding.

My biggest complaint is the first hour. Wallace Shawn (or “Wally,” as Andre calls him) is nervous about having dinner with someone who may be off his rocker, so he decides that he’ll be inquisitive and just ask questions. He sticks to this decision, but it is clear that his questions are no longer based in social anxiety, but instead fascinated curiosity. He gets Andre going, and to steal a word from David, that man can yak! He talks about everything from going to Poland to put on a play in a forest, theater troupes, Tibetan culture, Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, Gregory’s Alice in Wonderland play, and scores of other stories. At one point when Wally asks a question, Andre chuckles. “You really want to hear this stuff?” he marvels. With a friend, one may be intrigued by endless stories and anecdotes. As a film-watcher, it was a test of patience.

When Wally starts chiming in is where the film finally finds its voice, and this is about the time I was reeled in. We had already learned about Andre’s philosophy of life, which is far from ordinary, and what most would think of as new-age, hippy nonsense. Wally could not be more different than Andre. For starters, he does not have the seemingly endless bank account. We don’t know how Andre maintains his standard of living and exotic trips, but Wally does not have that luxury. He had an upper-class background living in the Upper East Side, but as he establishes early on in the film, ”now at 34 as an actor and playwright, all I think about is money.”

You could say that Wally is a pragmatist, while Andre is a spiritualist. Wally appreciates the creature comforts that give him more convenience, whereas Andre would rather live with a life of austerity so that he can better enjoy the little pleasures. The film heats up in the second half as Wally comes out of his shell and challenges Andre’s assertions, the same ones that he was captivated by during the first hour of the dinner. There are a few topics that become points of contention, and these two intellectuals hash out which is right. There is no correct answer. The most important part, from both sides, is that the questions are asked.

During the early diatribe, Andre talks about how he occasioned on a surrealist magazine printed in the 1930s. He turned to a random page and found four names. Three of them were Andre and the other began with an A. There was also a reference to Alice in Wonderland, and he later found out the magazine was printed right before his birth. Andre took this as a sign. He was fated to pick up that magazine and derive meaning from it.

Wally returns to this story and basically calls him out for being self-absorbed. He sees it as a coincidence. There were many people involved with the creation of the magazine. Were all of their actions — including the writing, editing and page layout – all for the sole purpose that some playwright having a mid-life crisis 50 years later would find it meaningful? He calls that notion ridiculous. Inconceivable! (sorry)

Wally uses the example of a fortune cookie. Of course he will read his fortune and have some fun with it, but if it forbid him to do something, he would not pay it much mind. After all, the creators of the fortune probably wrote hundreds, all in a fortune cookie factory somewhere. How could this company of fortune cookie manufacturers have any practical insight into his life? It is pure coincidence in Wally’s mind.

The above example is just one of many. It is not just eastern versus western thought, but in a sense even science and technology versus religion and spirituality. It is deep. Even though they respectfully disagree on some points, like the magazine, they do see eye to eye on others. They agree that people are living without sensation. Andre calls these people brain dead. They need to be shaken up and given a jolt, but of course Wally sees going to the Himalayas and hanging out with Tibetans as overkill. They do agree that people need to somehow escape their dream lives and truly live.

Just because of the narration, we see the perspective of Wally. By the end of the film, yes after all courses (spoiler alert: they skip dessert and order espresso), he has reached a new level of understanding. He has been shaken up. While he isn’t about to start thumbing through surrealistic magazines or give up his electric blanket, he does realize that he has become distracted by the trappings of his life. If we were to see Andre Gregory’s perspective, he would have likely been similarly moved. He probably listened to Wally’s points that there can be practical constraints to abide and still life a fulfilling life.

Even though the barrier of entry is not exactly easy, once comfortably pulled up to the table, I was intrigued and moved. Many of the notions about how one lives their life are profound. While few would agree with all of their points, everyone can learn something about themselves in the faces and voices of Wally and Andre.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Andre Gregory and Wallace Shawn: 2009 Interviews with Noah Baumbach.

Andre – Met Wallace Shawn (Wally) because he made an inquiry into one of Gregory’s plays. Shawn loved it so much that he wanted to go every night, but couldn’t afford a seat. So they gave him his own seat.

The idea came about because he had told Wally all of the stories, and it was Shawn’s idea to put them on paper. Gregory was sure that if it got made, that nobody except for their friends would want to see it.

Took it to Mike Nichols, who couldn’t do it. Through friends of friends, Louis Malle got the script and called him. He practically begged them to let him be involved, and insisted that there not be any visual distractions.

He uses four different voices in the film: 1) Theater guru. 2) Off the wall, spacey rich kid. 3) Spiritual used car salesman. 4) Sincere, later in the movie. This became a character based on Andre Gregory, but was not the real Andre.

Wallace – When he was 27, he had strong feelings about theater and was easily influenced. Fear has been a big part of his life. He was afraid to see anything in the theater that would compromise him. He was afraid to see the Andre Gregory version of Alice in Wonderland, but his friend urged him to see it. He was astounded. After seeing it a few times, he brought an envelope of his plays to Andre, but nobody liked them. Andre was the exception. He loved his plays and invited him to work with his company.

Malle was superb. He captured things in Andre that Shawn would not have expected. Even today Shawn cannot watch the film because it is too difficult. Off the set, Malle was “ill at ease,” but on the set he was affectionate and a tremendous storyteller.

The original script was three hours. They spent months cutting it down by an hour, and Louis cut down 15 more minutes in the editing room. It sounds like Shawn and Malle did not get along all that well. “He liked me as an actor,” … “but not as a writer.” Shawn said that he would have filmed the original script, so it sounds like they had some animosity about scenes being cut. As for Malle and the arguments about cutting scenes, “he lost a few, and won most of them.”

”My Dinner with Louis”

Wallace Shawn and Louis Malle meet at dinner for a 1982 BBC episode of Arena. They meet in Atlantic City, fittingly, and the episode is structured similarly as My Dinner With Andre, with Shawn giving the opening voiceover. They even show the intro to the film. One big difference between this dinner and the one with Andre is they use visual elements, such as clips and stills, which is more fitting given then subject.

This is the supplement I was looking forward to the most, and it delivered. I’m fascinated by Malle as both a director and a person. He doesn’t get the critical glory as a French New Wave director such as Godard and Truffaut, but you could argue that he’s taken more risks. This film is unquestionably a risk. One of my favorite film books was Malle on Malle because he tells such amazing stories. Here he talks about the controversies surrounding his films, beginning with The Lovers, continuing with Phantom India, Lacombe, Lucien, Atlantic City, and ending with My Dinner With Andre.

Criterion Rating: 7.0

The Confession, 1970, Costa-Gavras

“An individual may be guilty not because he is guilty, but because he is thought so.”

“Confession is the highest form of self-criticism. And self-criticism is the principal value of communism.”

The above two quotes are pulled from the film, and I feel that they cut to the heart of the message and subsequently the experience of Artur London (Yves Montand). The first is told in voiceover as something that London learned himself during his years in the Communist Party, while an interrogator tells him the second quote in order to coerce confession. The phenomenon revealed in the film is that through various physical and verbal tactics, one can subjugate a human being and cause him to betray himself. They use ideology, in this case communism, to convince him that he is doing a greater good through this act of self-condemnation.

London is a high-ranking Community Party official during the Stalin era. He lives comfortably in his privileged position. He has what appears to be an upper class lifestyle with his wife (Simone Signoret) and daughter. To his surprise, he finds himself being followed by a car. Later he sees two cars. Soon enough, the following turns into a full scale chase. He is cornered and taken prisoner. For what, he has no idea. The film language during this opening sequence is high action, and they use his thumping heart-beat to inject the tension, which will be used again later, although the majority of the film is not action-packaged but instead dialogue-driven.

When taken prisoner, London protests: “I demand to see a party representative.” He is promptly told that, “you aren’t seeing anybody.” He will figure out soon enough that it is the party that has taken him prisoner. They have betrayed him. Those who are familiar with Soviet history under Stalin know that there were many purges, false imprisonments and exiles of anyone who threatened Stalin’s power. The man was arguably paranoid, and he rid himself of anyone who achieved any sort of political power. The order to imprison London most likely came from the very top, as it did for many of London’s associates. A few of their stories will be told throughout the film, and most often they end with execution.

As the title indicates, they want a confession. Of what, London is not immediately sure. As far as he knows, he has not wronged the party. He has been a loyal member and subject. When badgered to confess, baffled, he says “Confess what? Ask me specific questions!” Meanwhile they play games with him. They lock him in a cell in the dark. They don’t let him eat or sleep. They essentially torture him. We will learn that they are not using these tactics to get immediate results, but as a mechanism to slowly and gradually break him down.

His wife is used against him. At one point he is told that she has repudiated him and taken up a lover. We learn later that this is not true, but is just another ruse to manipulate their prisoner. In reality, she writes numerous letters to the Minister, urging for answers. We see her visit the Minister, asking whether he has been arrested and what he is charged with. She is told that he has not been arrested, but that “it is a serious, confidential party matter.”

The film is nearly 2.5 hours long, and a large portion is spent on the interrogations. These scenes may not seem too exciting on paper, but they are actually quite engaging. The back-and-forth is in a way exhilarating. We see the harsh methods that his captors use to urge him closer to the confession that they want. They play with wording. For instance, they are interested in his interactions with an American spy named Noel Field, who gave London money in 1947 for humanitarian reasons. Field was not revealed to be a spy until 1949. London rejects the statement that he was paid by an American spy because he did not know Field was a spy at the time. Each time he dissents, he is taken away and tortured. Eventually he makes small confessions and is rewarded. When these short, signed statements are put together, they create the illusion that London was being paid for actions he did for a spy. A collection of true facts with misleading wording tell a big lie.

They tell London that the only way out is through confession. They tell him that all the others that have confessed are out of prison. These are all lies. Many of those that confessed have long since been executed.

Eventually London breaks down. Even though it is difficult to watch and hard to fathom, Montand gives such an amazing performance that makes us understand the character evolution. First off, he lost a tremendous amount of weight during the filming, approximately 25 lbs. He looks physically and emotionally emaciated. I have long thought that Wages of Fear was his best performance. Not any longer. He gave every bit of himself to this role. I know that actors put can themselves through a lot when committing themselves to a role, but few sacrifice as much as Montand, which makes sense since his character also sacrifices so much. Even without the physical transformation, Montand is captivating throughout the performance, whether he is voraciously battling his accusers about semantics, or when he is worn down and giving them what they want.

Combined with the torture and the party rhetoric, London does break down. He gives a full confession, which leads us to what would later be considered a “Show Trial” that was broadcast on the radio. It was a show because of all of the testimony was manufactured. We only see London’s experience, but the same type of ordeal happened to the dozen or so people that he stands trial with.

Costa-Gavras was accused of making an anti-Communist film, which he defended himself against. He says that he was making a film that condemned totalitarian rule, and that Stalin communism should not be confused with other communism. In my opinion, it does come across as anti-Communist, but not for the reasons that he intended. Through the party, the opportunity was created to allow these crimes against humanity. While Stalinism is without question the worst, there have been scores of Communist leaders that have controlled through totalitarian methods. There still are a few that exist today, most notably in North Korea.

Costa-Gavras is correct that any political philosophy can have dangers if used to betray their own citizens. This is portrayed in the final act of The Confession because it is the “good of the party” rhetoric that takes London down to the road to cooperation. However misguided, he firmly buys into the fact that his confession is the right thing to do. His captors tell him to, “trust in the party. It’s your only chance.” He believes them and does trust in the party, the same people who have tortured him for nearly two years. The notion that he is acting as a good communist by cooperating is absolutely dangerous.

Film Rating: 8.5

Supplements

You Speak of Prague: The Second Trial of Arthur London: Documentary from Chris Marker.

Chris Marker worked on the production, and while doing so, filmed a behind-the-scenes documentary about the production. Even though the subject is the film, the style is distinctively Marker.

He begins with the “real” mock trial of Arthur London, part of the Slánský trial, which was the last theatrical trial because it happened a few months prior to Stalin’s death. Slánský testified to not being a real communist, but not because it was true. This was because Stalin wanted him to say he was not a real communist. 11 of the 14 accused we executed.

As he introduces the behind-the-scenes footage, he describes the film via voiceover narration as “the tragedy of a Communist trapped by his loyalty.”

He interviews London, Montand, Signoret, Costa-Gravas, and others. He also tells the story of what happened after the film, how it was attacked and that London had to go back on trial in what was then Czechoslovakia.

Costa-Gavras at the Midnight Sun Film Festival: 1998 Conversation with film scholar Peter von Bagh.

He grew up in Communism and his father had participated in the resistance and was arrested afterward. Costa-Gavras and his family had a difficult time. He discovered films when he left the censored Greece for France in 1955. Despite the political difficulties, he and his brothers were raised well. He worked with Claire, Demy, Clement, and others. He liked working with Demy because the style and manner with actors was different.

He came to thrillers by accident, although he defends them as a narrative artform, giving an example of Greek texts that were thrillers. Coming to learn about Stalin helped develop his feelings about politics. The 1968 riots also changed his outlook quite a bit.

He speaks very fondly about Yves Montand and his political passion. At one time the French had conducted a political poll and Montand had 30% of the country that wanted him as president. We saw some of that passion in the Marker documentary.

That segues them to The Confession. Claude Lanzmann of Shoah actually told him to read the book, but it would be hard to adapt as a movie because it was 500 pages. Z had not come out yet, so that success did not help. The visuals, including archived footage, had not been done before. Costa-Gavras used this footage as a way to not show the constant question and answer sessions, because those exchanges are heavy in the book and would drag down the film. One interesting comment is that “most of us are bad guys for someone, whether we realize it or not.” He is not forgiving Stalin, but accepting that everyone has the capacity for evil.

Portrait London: Artur and Lise interviewed for French television in 1981 to coincide with the release of Iran hostages.

London says that he was a victim of Stalinism, not Socialism. He says that is like confusing the Inquisition with Christianity. During captivity he thought a lot about his wife, family, and his ideals against fascism. This is told well in the film. Even though the experience was terrible, the foundation of his beliefs withstood. He compares his incarceration with the American prisoners in Iran, and says there is no comparison. They were treated well from what he understood.

Yves Montand: 1970 interview.

The interviewer says it is not an “after dinner” film, but Montand is quick to point out that it is an entertaining film. It is a thriller. They talk about the process of making the film. They shot the “after” scenes first, because he had not lost the weight yet. Then he started losing some weight for the early scenes, and then it plummeted when he was being tortured. He basically had to go on a hunger strike.

Françoise Bonnot: 2015 interview with the editor of multiple Costa-Gavras films.

Her mother, Monique Bonnor, was an editor that worked on a number of Jean-Pierre Melville films. Françoise worked with her as an assistant, and came to work with Costa-Gavras first on Z. He wanted to be in the cutting room with her, and she had to ultimately kick him out. She was shocked to get the Oscar for Z. It was thought of as impossible for a French person to win. For The Confession, the dailies were put together so well that the editing was not as difficult. One challenge was she could not linger on the rough shape of Montand as prisoner because that would be too uncomfortable for the viewer.

She likes her editing to be “fluid,” where the editing is invisible. It seems like a continual motion to the viewer. She thinks the film came out well. The torture scenes could have been cut a little bit, but she still feels like it flows well.

John Michalcyk: 2014 Interview with writer and filmmaker, who wrote a book about Costa-Gavras.

People saw him as a stereotypical leftist political thriller director. The Confession is less of a thriller. It is a different type of intensity. Z has a quick progression and it is more exhilarating, whereas The Confession is slower and more deliberately paced.

The film attacks hypocrisy. At the time people did not know about the show trials. The Americans were mostly not even aware of them. The Soviet symbols were very much in the public consciousness in 1970. Michalcyk calls his approach not communist, not socialist, but humanist.

Criterion Rating: 9/10