Category Archives: Film

The End of the Studio System, Part 3

THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL

This is the third post of three that is part of the Classic History Project Blogathon hosted by Movies Silently, Silver Screenings, and Once Upon a Screen, and sponsored by Flicker Alley.

Part 1: The Foundation Slips

Part 2: The Beginning of the End

During the 1950s, the film industry crashed precipitously. By 1953, only half as many people were seeing movies in theaters as they were the decade before. By 1957, only 15% of the population went to the movies at least once per week. Meanwhile, the US was in the midst of a post-war economic boom. People had money to go to the theaters. Why didn’t they?

It is too easy and convenient to pinpoint the Paramount Decision of 1948 as the reason for the downfall of the studios. It surely was a catalyst, but there is no single answer. Divorcement was one of many reasons for the downfall of the studio. A lot of people blame television, which is also fair, but again, just one of many reasons for the decline. It was a perfect storm of legislative, technological, and socio-economic changes that drastically reshaped American society, and subsequently, American media.

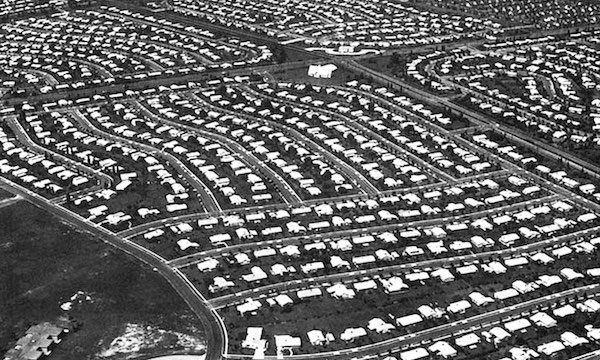

MIGRATION

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the armed forces returned home to economic prosperity. With improvements in automobiles and extra disposable income, people had the opportunity to move away from the big cities and into the suburbs. Levittown is a famous example of these communities, but there were many like it. The suburban sprawl began rapidly in the 1950s and continued gradually.

Another major driver of this migration was the Baby Boom. People were having kids and wanted to live in quieter, more relaxing places to raise them. This was the age of the nuclear family, and people wanted to spend their time raising children or participating in family and group activities.

It was not easy to bring movie theaters to the suburbs. The old movie palaces had been urban spectacles — vast buildings that were usually in the heart of downtown and could hold massive crowds. These theaters attracted people to the city and were the source of the studio profits. As people moved away, these large palaces eventually faltered. It was a challenge to bring movies out to the suburbs because the population was so scattered.

ECONOMIC BOOM

With this new period of prosperity, people wanted to spend their money on more substantive activities than going to the movies. As noted earlier, the movies were seen as low cost and short duration entertainment. People wanted to spend their money and time on memorable adventures rather than fleeting escapes from reality.

This was also the time period where the 5-day work week was becoming the standard. People had their weekends free and wished to spend them on activities such as homemaking, gardening, and sports. With transportation and money to burn, people wanted to see the world on vacations rather than see artifice in the movie theater. Prosperity actually hurt the studios.

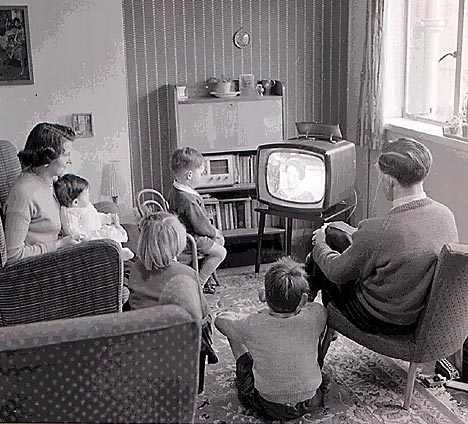

TELEVISION

The role of television in the downfall of the cinema is hotly debated. Many consider it to be a direct cause for the studio’s demise, while others see it as more of a symptom of the economic transitions happening in society. Regardless of where experts stands on the topic, television was a factor. It quickly became a popular appliance and allowed people the convenience of consuming media at home rather than going to the theater.

The television boom began in the late 1940s and continued throughout the 1950s. The growth was rapid. By 1960, 87% of the population had a television. Unlike the movies, where people sit in dark rooms, television was a social activity. People would gather together and watch a program at somebody’s house.

The programming on television was passive and light, not as deep and profound as that seen on the silver screen. Much of the programming on television replaced the B films that the studios relied on for small profits. Television also took the pre-movie content away from theaters, such as cartoons, newsreels, and short films.

THEATERS IN THE 1950s

The large movie palaces gradually went away in the 1950s. They were replaced with arthouse cinemas, which would attract a higher brow, more intelligent and sophisticated moviegoer. The demographics for these films were older and more cosmopolitan. Many of these audiences watched films that are discussed here at this blog.

There was a foreign film boom in the late 1940s and 1950s, many of which took hold and became popular in the United States. Among these imports were the post-war Japanese (Kurosawa, Mizoguchi), Italian Neorealism (De Sica, Rossellini, Fellini), French noir (Melville, Clouzot), and later the French New Wave (Godard, Truffaut). Foreign films were not subject to the Hays code and often were provocative with sensual situations. Bitter Rice was a film that was noted for sexual suggestion. The Bergman films of the 1950s also titillated audiences, such as Summer with Monika as an exploitation film. Compared to the American films, the audiences were still small, but these foreign films pushed the boundaries and played a part in removing the Hays Code.

One creative way to get theaters to the suburbs was through drive-in movie theaters. They were relatively easy for exhibitors to open because there was plenty of land available in the suburbs. We think of the drive-in theaters differently than what they were in the 1950s. They were not just for watching movies, but were a hotbed center of activity. Of course there were the movies, but there was also food and other amenities. Some would even offer laundry services. The drive-ins were eventually seen as immoral and degenerate. Kids would use the drive-thrus as a place to discretely bring a date or get into trouble.

The next suburban theater was a bi-product of the advent of the shopping mall. Every mall would eventually have a multi-plex and most still remain today. The reasoning was that the mall would draw consumers, and movies were a way to take a break between shopping.

THE STUDIOS ADAPT: TEENPIC

This may seem incomprehensible, but the studios had not done any major market studies prior to the 1950s. However hubristic it may sound, they did not have to prior to the 1950s. So many people went to the movies that it was almost a waste to track where they came from. Prior to the 1950s, they ignored teenagers because they thought of films as family outings. As the war babies started to reach adolescence in the 1950s, they became a large market with free time and allowances to spend. During this time, Hollywood finally started using modern marketing techniques and determined that teenagers were regularly going to the movies. They subsequently targeted these teenagers with their content.

Even though it was a social picture, Blackboard Jungle was a surprise success. It was also notable for using a rock and roll song, Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock. In 1955, Sam Katzman ushered in teenage rock and roll movies starting with the film version of Rock Around the Clock. This trend continued, and soon Elvis Presley movies gained traction. His debut was in Love Me Tender, which was successful due to his popularity with teenagers. He starred in a total of 33 films, most of which range from bad to mediocre, but they attracted fans. There were plenty of other teen film franchises. Gidget was hugely popular and started a franchise of its own, plus it ushered in the Beach Party film. Teenagers came out in droves to watch these movies.

THE STUDIOS ADAPT: TELEVISION

As already discussed, television began by piggybacking on the radio concept of nationwide “live” content. That carried them for a short while, but soon a more diverse range of content would hit the screens. The studio system is responsible for much of this content.

The independent producer model took hold with television. Major Hollywood players began dipping their toes into television in order to make profits. David O. Selznick came out of retirement to do this very thing. He achieved success with a program called Light’s Diamond Jubilee, which was broadcast on all four networks and seen by 70 million viewers. This was a staggering number for the time period. Other similar jubilees preceded Selznick’s and would follow him. As he was before with film, he became obsessive with the project and this was the final Selznick TV production.

The most notable independent production company was Desilu, founded by Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, and popularized by their hit show I Love Lucy. That was not their only success. They would release The Untouchables, Star Trek and many others. Delis proved that independent producers could become television tycoons.

Eventually all of the major studios would transition to television. As already discussed, Disney was the first to find success with Disneyland and later Walt Disney Presents. After early failures, the studios gained a foothold in this new arena. They still had studio space that was not being used, so they started putting together television programming. Warner Brothers signed a deal with ABC and launched Warner Brothers Presents, which was their first foray into television. They continued their relationship with television, using the same production methods as their old B movies and found success in television. They became known for their westerns like Cheyenne, Maverick and Sugarfoot.

Universal/MCA became the unquestioned leader among studios in television production. Their continued production of B pictures after the Paramount decision helped for a smooth transition from the large to the small screen, and they transplanted many of their successful film franchises to television. They also launched popular shows of their own, such as Leave it to Beaver, Alfred Hitchcock Presents and several others. Today they are a multi-media conglomerate, NBC Universal, that own various entertainment properties.

THE FUTURE STUDIO SYSTEM

As the tumultuous 1950s ended and the 1960s began, the studios had reached a level of comfort and stability. They all continued working in television, using their facilities for new programming, and they continue to be major players in television today.

The independent producer model, as previously discussed with Selznick, became the norm. Professional producers such as Hal Wallis and Robert Evans worked closer alongside the studios and the talent. Evans had previously been head of Paramount until he obtained success with Chinatown in 1974. He then stepped down and worked as an independent producer, yet he continued to produce films for Paramount.

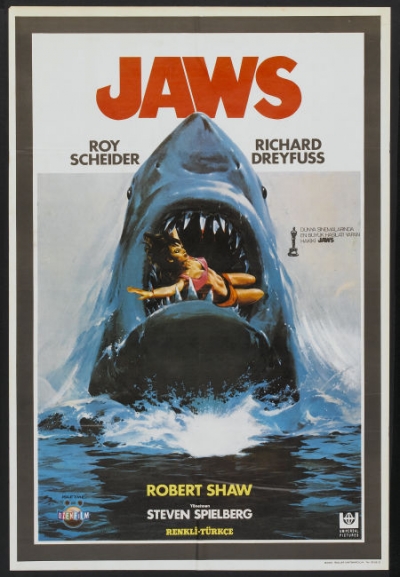

Steven Spielberg’s Jaws was the first blockbuster hit, and it revived the studio system to a certain degree. They were still divorced from vertical integration, but they began to focus on large blockbuster releases, a trend that continues today. One could argue that Jaws saved the studios, and ever since they have relied on blockbuster franchises for their core profits.

WHERE ARE WE GOING?

We are now in the digital age, which seems to be another period of transition. Box office revenues are still high, but more and more people are watching movies at home, either through streaming services like Netflix, Amazon, Hulu or Video on Demand. Premium content that used to be found only on the large screen as a film can now be found on cable as an expensive mini-series. Popular shows like Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead would not have a chance twenty years earlier.

Predicting the future is impossible, but sometimes the past informs the future. We could be heading into another transition into the digital change that will change how people consume entertainment in the future. Only time will tell what this will mean for cinema, television, and visual media in general.

SOURCES

- Anderson, Christopher. Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties.

- Maltby, Richard. Hollywood Cinema.

- Sarris, Andrew. The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968.

- Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era.

- Staiger, Janet. The Studio System.

- Staggs, Sam. Close-up on Sunset Blvd: Billy Wilder, Norma Desmond, and the Dark Hollywood Dream.

Top 20 of 1936

1936 was a phenomenal year for French film, perhaps among the best ever. There are six French films on my list, all of which are in my top ten. Of course I’ve made it clear that 1930s French film is my favorite era of all time, so this should come as no surprise. There were also three Japanese films, all early pictures from future masters Mizoguchi and Ozu.

Someone noted in our group that this was quite the year for William Powell and Jean Renoir. This is absolutely true for Powell, who not only starred in Best Picture winner The Great Ziegfeld (not on my list), but also starred in what many consider to be among the best screwball comedies of all time, My Man Godfrey. On top of that he reprised his role of Nick alongside Nora in After the Thin Man.

Jean Renoir’s year is seen as fantastic only in retrospect. It was most likely a tough year for the man. My favorite work of his for the year, A Day in the Country, was a frustrating shoot for him and he left before the film was finished. The Crime of Monsieur Lange was successful, but also controversial and leftist. He also participated in La vie est à nous, a leftist propaganda documentary that I have not seen. He was embroiled in the politics of a volatile time.

There are a couple of notable omissions here, some of which will seem sacrilegious to classic film fans. Mr. Deeds Comes to Town is an example of the type of Capra film that does not work for me, unlike It Happened One Night. There are a few other Capra films that’ll be omitted from these lists, although I plan to give Lost Horizon a fair chance for my 1937 list. Another omission is Swing Time. There’s no doubt that Astaire and Rogers were a talented duo, but I’m not as big a fan of their acting, and their style of musical isn’t exactly my tastes. Show Boat and the Lubitsch musicals are my preference.

1. A Day in the Country

2. My Man Godfrey

3. Modern Times

4. The Crime of Monsieur Lange

5. La Belle Equipe

6. Show Boat

7. Story of a Cheat

8. Sabotage

9. Mayerling

10. The Lower Depths

11. Dodsworth

12. The Only Son

13. Secret Agent

14. Redes

15. Sisters of the Gion

16. Osaka Elegy

17. After the Thin Man

18. Fury

19. Libeled Lady

20. The Charge of the Light Brigade

The End of the Studio System, Part 2

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

This is the second post of three parts that is part of the Classic History Project Blogathon hosted by Movies Silently, Silver Screenings, and Once Upon a Screen, and sponsored by Flicker Alley.

UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), the Hollywood Ten, and the subsequent blacklistings are large topics in their own right. They did not directly impact the downfall of the studios of the system, but they were yet another symptom that something was broken. The anti-communism movement and the fallout contributed to a great deal of pessimism within the industry, while also removing talented individuals that included actors, directors, writers, and even common crew.

The hearings and inquiries into Hollywood began in 1947 where they were trying to identify Hollywood filmmakers who had ties to the Communist Party, and were subsequently trying to influence Americans with a leftist agenda expressed through film. The Hollywood Ten refused to testify and were blacklisted. Many other notable individuals would later be blacklisted, including Charles Chaplin, Orson Welles, Martin Ritt, John Garfield, Judy Holliday, Dashiel Hammett, and countless more. Some cooperated and testified, naming names. This list included Elia Kazan and Sterling Hayden.

PARAMOUNT DECISION AND REPERCUSSIONS

The Paramount Decision of 1948 was the smoking gun that effectively ended the studio system’s dominance of the industry. All of the tricks like block booking and blind bidding were immediately abolished, once and for all. The entire decision can be read here. It was a detailed decision and a pointed one. The studios had to divest themselves of their theater holdings and operate as production companies only.

The decision was devastating and there were major repercussions. Overnight, the landscape had changed and the studios had to make drastic operational changes. The fallout would pave the way for television and a new era of Hollywood filmmaking.

Since the studios could no longer push their lower quality inventory on theaters, they had to scale back on B picture productions. Most of the studios focused solely on A pictures. This meant there were also fewer overall productions. This meant fewer jobs, at least in film.

Each studio transitioned differently. Universal was one of the outliers that remained in the lower grade feature or B picture business. They revived the Abbott & Costello franchise, and originated some other franchises that would eventually land on television.

The studios now had to make deals directly with the talent. In this new world, they resembled the independent systems like the Selznick system. Since they had lost leverage, the negotiations were not always in their favor. They made deals with filmmakers, such as Alfred Hitchcock as independent producers and directors. The talent that was in demand held substantially more leverage than they did under the old system.

The directors, actors, and all of the talent were essentially free agents. They made films for different studios. During what most consider to be Hitchcock’s best work in the 1950s, he worked primarily with Warners and Paramount, but he made North by Northwest with MGM. Directors like Hitchcock developed more into auteurs, whereas in the previous system, producers such as David Selznick and many others (Val Lewton for instance) had some sort of authorial control.

TRANSITIONS

Each studio handled the changes differently. With television coming into play, the industry was shaken up dramatically. At first the studios were reluctant to get into bed with television, which they saw as competing for the same viewers, although that changed once some social-economic realities set in.

Lew Wasserman formed MCA, basically a talent agency, and he became a power player in the scene. He functioned similarly as David Selznick did in the 1940s after getting out of feature production and farmed out talent to the various studios for a profit. MCA acquired talent such as Jimmy Stewart, and leveraged them against the studios to benefit their clients. One of Wasserman’s major deals involved Jimmy Stewart and Universal, where he negotiated a tax-friendly deal for Stewart to get a large percentage of the profits. This in a similar vein as the deals that Capra and others had made to get paid in capital gains, although far more generous. Stewart was able to obtain 50% of the profits of Anthony Mann’s Winchester ‘73. This was an unprecedented number, and Stewart was also more involved in other aspects of the production. This was new and shaky ground for the studios.

Here is an interesting and not very flattering piece on Wasserman from Slate.

Studio head Louis Mayer left MGM in 1951 after a power struggle with Dore Schary, the then head of production. This turned out to be a fortuitous move for MGM, as they were able to survive under Schary under the strength of the musicals. Musicals such as Singin’ in the Rain and An American in Paris were massive moneymakers for the studio, and there were plenty other successful musicals on a smaller scale. The studio continued churning them out and they outlasted all other studios at remaining profitable and prominent without making drastic changes. By 1955, most of the musical profits had run their course and MGM transitioned just like the rest of them.

THE STUDIOS AND TELEVISION

There was reluctance for the studios to transition to television. It was thought to be a lower quality product, and in the beginning, that was true. At first there were mediocre offerings with an emphasis on being “live,” which is something that separated TV from film. Over time, the TV content transitioned to resemble the B features that the studios had formerly cranked out. In many cases, the same studio lots that were used for B films were used for TV shows. As the film industry went through a downfall, they had no choice than to jump into the arena.

By 1955, most studios had made their attempts at launching television programs. Disney, MGM, Warner Brothers, and 20th Century Fox all made attempts, yet few of them were successful. Disney was the only significant success with their show Disneyland, which was partly because it was tied to their popular theme parks. Many studios noticed how well Disney was able to transitioned and tried variations with mixed results.

A watershed moment came when The Wizard of Oz was licensed to television and scored huge ratings. The studios again took note and unloaded their film inventory to television for large sums of money. Television became a second-run outlet for older film inventory. Back in those days, there was not much of a secondary market for film inventory, so this was a pivotal moment.

There will be more discussion of the studios and the transition to television in the next section.

Next: The Downward Spiral

The End of the Studio System, Part 1

THE FOUNDATION SLIPS

This is the first post of three parts that is part of the Classic History Project Blogathon hosted by Movies Silently, Silver Screenings, and Once Upon a Screen, and sponsored by Flicker Alley.

These essays are based on previous research that I have done and I will share my sources at the end.

POWER

On an early 1948 evening, the Wilders and Goldwyns dined together at a Romanoff’s in Beverly Hills. It was a popular restaurant for the industry, with many top-flight stars showing their faces regularly. The foursome’s dinner was interrupted by an elderly, disheveled man, looking gaunt and possibly drunk. He approached the table and gave Samuel Goldwyn a tongue lashing, criticizing the mogul for the unwarranted success he had achieved. He ranted that “here you are, and I ought to be making pictures, I’m the one.” Goldwyn was shaken, and after the man left the table, revealed him to be none other than D.W. Griffith, one of the most important and influential silent filmmakers that ever lived. The system had made him, and then chewed him up and spit him out. A couple of decades later, and it could have been the studio system saying the same thing to another dinner party.

The studio system was a behemoth. They consisted of the “Big Five,” which entailed Fox, MGM, Paramount, RKO and Warner Brothers, plus there were also Universal, United Artists, and Columbia, often referred to as “the other three” that had plenty of power. The studio controlled the movie process from production to distribution to exhibition. They wrote contracts with actors, writers, directors, producers, and virtually all involved with the industry. They released the “A” pictures (prestigious star vehicles) to the movie palaces, while the lower budget films, often genre or from recycled scripts, comprised the “B” pictures.

During the Great Depression, films were considered to be a populist, relatively inexpensive form of entertainment. Much of the content of the films of the 1930s pandered to the masses, and despite experiencing losses during a few bad years, the studios more or less continued to rake in the profits. During the Second World War, they experienced a boom and seemed to be able to do no wrong. Because of their absolute control and success, they were blinded as to what was taking place behind the scenes that would result in their undoing.

INDEPENDENCE

The move towards independent production started early. There were many wunderkind producers that worked at the major studios. Irving Thalberg was one such youngster who seemed to be able to do no wrong, producing hit after hit for MGM, but he died at a young age. David O. Selznick was another young, successful producer, and he was far more ambitious. He began his career during the silent period at MGM, and then moved to Paramount, RKO, and then back to MGM.

Selznick was confident in his abilities, yet resented the studios for profiting off of him. He decided he wanted to become an independent producer. He was not the first to attempt such an endeavor. United Artists was put together by a number of powerful industry players, including D.W. Griffith and Charles Chaplin, but Selznick’s vision was different.

Selznick founded Selznick International Pictures (SIP), and worked independently as if he were at a studio, yet he was aligned with the studio system. He would produce “A” pictures, choosing top-flight directors, actors and crew without the constraints and meddling of the studio chiefs. He had an obsessive personality and would micro-manage the projects. In many respects, he was at least partly the auteur of his works. Years later, Alfred Hitchcock would do his editing within the camera in order to maintain some sort of creative control of his pictures made with Selznick.

Selznick has his critics, but he was undeniably successful. He released a string of hits, notably A Star is Born, Rebecca and Gone With the Wind. Winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards for the latter two in consecutive years.

Selznick was as successful a talent scout as he was a producer. He was particularly fond of finding leading ladies, such as Ingrid Bergman and Joan Fontaine. He also “discovered” Alfred Hitchcock as a director and brought him to work in the United States with a seven-picture deal. He would contract with them directly through SIP, and if he was not ready to make a picture with them, would farm them out to other studios. As his clients stars rose, so did their fees. Eventually Selznick would become exhausted by the intensity of movie producing, and would lend his stable to studios. He would charge them the going rate, pay his talent based on the contract, and pocket the difference. This amounted to millions of dollars.

ANTI-STUDIO LEGISLATION

During the 1930s and 40s, the Department of Justice was taking a close look at the studio system. They felt that the studios were using unfair trade practices when distributing films to theaters, leveraging their power to get the chains to take inadequate deals. The primary tactics that the DOJ frowned on were block-booking and blind bidding.

Block Booking was the practice of selling a block of films to the theater. This usually would consist of one or two A pictures that would be guaranteed to give them a profit, and a handful of B pictures that may not be as successful. The A pictures were rarely parceled out on their own. It made business sense for the studios because they wanted to find screens for all their pictures, but the DOJ correctly thought that this practice was unfair for the exhibitors. Blind Bidding is just what the name implies. The studios would sell pictures to theaters without letting them see the film. Sometimes this would happen before picture had been produced.

Anti-Trust Decisions: From 1938 to 1940, there were a series of decisions that limited block booking, blind bidding, and other unfair trade practices. The first decision in 1938 was targeted towards all eight large studios, while the latter decision in 1940 was limited to the five majors. The repercussions of these decisions actually benefited the studios. They had to cut back on B pictures and focus on larger A productions. Because of the film boom during the war years, this helped the studios as the large productions were overwhelmingly successful and profitable. Losing the B pictures helped them slim down their overhead.

Revenue Act of 1941: With an expensive war in process, the need for tax dollars rose. The Revenue Act was passed in order to impose high tax rates on people who were in the upper tax brackets. There was approximately a 70-80% tax rate for those earning $200,000 annually. Of course a lot of the stars in Hollywood, behind and in front of the camera, earned salaries of this magnitude. For instance, all three of the leads of Double Indemnity earned $100,000 for their roles. Under the Revenue Act, they would have to pay roughly $80-90,000 to the IRS.

The repercussions of this legislation pushed the talent closer to independence. Rather than continue to pay flat fees, the studios changed contracts so that the talent would get a percentage of the profits. This meant that they would be taxed as capital gains at a far lower tax rate. Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe was one of those first deals.

Olivia de Havilland Decision: The star actress wanted out of her contract and the studio was effectively holding her hostage, unable to leave for a rival studio. She sued successfully to get out of her contract. The ruling kept the studios from adding suspension time to contracts to keep them from being free agents.

Post-war DOJ Initiative: With the studios continuing to be unfettered by any government intervention, the DOJ wanted to move aggressively at breaking up the studios. The issue at hand was the amount of the control. The studios were by definition a monopoly, vertically integrated to control production, distribution and exhibition. The DOJ wanted to break these three pieces up.

INDEPENDENT FILMMAKERS

As contracts ended, directors wanted to follow the Selznick model and forge their own independent companies. Several famous directors took this route and released films under their own “studios.” Some of them were more effective than others. Some of the filmmakers would remain independent, while others would return to the studios.

Alfred Hitchcock, reeling from his bad deal with Selznick, created Transatlantic Pictures. Under this company he made Rope (1948) and Under Capricorn (1949) with more creative freedom. Rope was more of an experimental film, and probably not one that would be possible for a filmmaker without Hitchcock’s caliber, and definitely not under the studio system. The experiment did not go as well as planned and was financially unsuccessful. The follow-up, Under Capricorn was less successful and that marked the end of the famous auteur’s independence. Hitchcock would make some of his best pictures in the 1950s for various different studios.

Frank Capra, William Wyler and George Stevens formed Liberty Films. Only two films were made through this company, and both of them were from Frank Capra. They were It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) and State of the Union (1948). It is difficult to believe given the reputation today, but It’s a Wonderful Life was a financial failure. This ended the project, with Paramount buying the assets and finishing the second Capra film. They also signed deals with the three principal directors. William Wyler made The Heiress for Paramount in 1949.

The most successful of these early director forays was John Ford’s Argosy Pictures. Ford had a lot going for him. For starters, he was reliable director, churning out quality content that did well at the box office. He was also an efficient director, usually coming in below budget. Ford did not strictly work on projects for his own company, working occasionally with the studios as needed, but he kept Argosy going for some time. Some of the notable Argosy films were Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Rio Grande, and The Quiet Man. Even with longevity and success compared to the others, a financial failure doomed his company and Ford also returned to the studios.

Next: The Beginning of the End

Summer With Monika, 1953, Ingmar Bergman

For this post I am mixing it up a little bit. Rather than do a formal review, I’m participating in MovieMovieBlogBlog’s Sex! Blogathon. Rather than do a formal review and/or analysis of this earlier Bergman film, I’m going to explore how sexuality was portrayed and how revolutionary it was in the world of cinema.

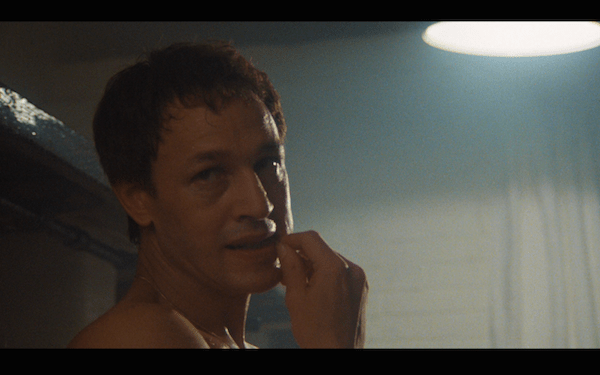

Monika and Harry are like many young, lusty couples. We see the courting process with them watching a romantic movie together. She is in tears while he yawns, which is typical, but through their brief time together they establish a deep, romantic connection. From there they escalate to a sexual relationship.

Even though Bergman had not launched on the internal stage just yet as a major auteur, by 1952-53, he had honed his filmmaking craft. The film language he used in films like Summer with Monika and previously in Summer Interlude would remain relatively constant throughout the rest of his career, but of course he improved and became more capable over time. He also showed early on a keen ability to demonstrate romanticism, sensuality and even sexuality. Because of the Hay’s code, American filmmakers had learned the power of suggestion through film language to hide the overt sexuality in film. Bergman borrowed some of these hints and developed a few methods of his own, but he also not afraid to dip his toes in the water and explore sexuality more directly.

We know that Monika and Harry begin an attempt at escalating the physical relationship because they are in the midst of some heavy petting when her father comes home. They quickly dress and act as if nothing was happening, which is a subterfuge that many (probably even Bergman) can identify with. They then meet on the boat and presumably have sex. They are in the same bed and there are vague suggestions at sexual activity. Harry loses his job and does not care. His new job is within the arms of Monika. As he ventures away from the city with her, we see the city from the boat’s point of view. The camera rocks back and forth, which we would expect from a floating boat, but in my opinion it is rocking because of the activities taking place within. Later in the film we learn that Monika has become pregnant. Conception most likely took place during these early scenes.

The sexuality transforms from suggestion to depiction as they reach the island. We first see Monika wearing a revealing bottom and a loose shirt, which she takes off. This is only the beginning of a series of scenes with a scantily clad Harriet Andersson. As they settle on the island, we see what is quite close to nudity. She faces Harry and removes her top, revealing her nude back. We then see her from Harry’s perspective, but his body blocks any nudity from showing on camera, yet his wandering hands clearly reach those same hidden areas. Monika gets up and runs to the beach and we see her naked behind, and then the film cuts to her in a natural pool. This scene is tame by today’s standards, but for 1953, it was quite scandalous.

The relationship and plot play out over the summer, and since this is not a traditional review, I’m going to skip these details. As they get settled back in the city, Monika becomes weary with her relationship and strays elsewhere. Bergman communicates this by simply having her look at the camera seductively when we know she is out of the house and away from Harry. This was also scandalous, because this was a sexually licentious woman. People in film were not often portrayed as straying from a committed relationship or marriage, even if it was only hinted at (although confirmed later) like in Bergman’s film.

In one of the final scenes, Bergman goes for the gusto. We see Harry raising his little girl, betrayed and rejected by Monika, but that summer still enraptures him. It isn’t clear whether the sexual escapades or the romantic moments are the most magical in his memories, but the version of Monika in the summer was a fairy tale. We see a flashback from his perspective of Monika in the same near-nude sequence as earlier, but this time the film does not cut as she runs to the beach with her rear exposed. She is fully nude, although this is a long shot so, again, not very explicit to modern eyes, but progressive for back then. Given that Harry remembers that one, erotic image, I think it was his personal sexual revolution that he longs for.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Ingmar Bergman Intro:

This is a brief introduction from 2003. Bergman felt affection for the film because of the way the screenplay came together, but also because of his introduction to Harriet Andersson. He had seen her in a stage play in fishnet stockings and lace, so he wanted her to be in the part. He did not go into the fact that they became lovers.

Harriet Andersson: 2012 Interview with Peter Cowie.

It had been 60 years and for her age, she looked remarkable. She speaks English well, with a strong accent. She talks about her origins in the industry, from being picked out to working with Bergman.

Bergman’s reputation in Sweden was very poor among actors at the time. He was reputed to yell and scream at them, and had his eye on young girls (which isn’t entirely inaccurate). She auditioned with an 8-minute shot where she was sketchy with her lines. She was surprised to get the part, which was a dream part.

She was not worried about the nudity. They were on an island so it felt natural, and the crew had seen it already. It felt liberating.

They talk about her looking at the camera, which was a scene that was appreciated by the French New Wave. She was shocked at the scene at first because this was something that wasn’t seen. People didn’t look at the camera. She thought it was strange, but went along with it.

Because of being lucky in getting this famous role, she was able to get roles with other directors and of course many future Bergman films. It was a break-out role for her.

Images from the Playground: .

This half-hour documentary is introduced by Martin Scorsese, who produced it through World Cinema Foundation. He was fortunate enough to live through Bergman’s career genesis from Summer with Monika up to Saraband. The documentary has behind the scenes footage from Bergman working on the film. It is from Bergman’s 9.5mm camera, and is almost like a home, silent video. It has narration from audio interviews of Bergman and his stable of actresses.

They talk about the production, such as Bergman discovering Harriet and talking about how gorgeous she was. It is interesting to see this commentary, but it is easier to just get caught up in the images and narrative. They take the documentary beyond just Summer with Monika. Bibi and Liv also participate. Bergman talks about the importance of all of these actresses and there are reflections on the fact that Ingmar was involved with them intimately at some stage.

This really is a magnificent little piece of film. It is the treasure of the disc.

Monika, Exploited!

Summer with Monika was a controversial picture in the states, and was hacked up and released as exploitation-fare with an English dub. This is an interview with Eric Schaefer who talks about how it became exploitation fodder.

During post-war period, distributors were importing films from overseas with adult content. These arthouse films were released in the exploitation circuit. Monika fit well with this market because of the brief nudity and sensuality.

Kroger Babb, an exploitation exhibitor, got the rights to Summers with Monika for $10,000. He then put in $50,000 into the film for cutting and dubbing. He got it through deceptive and suspect means, and Svensk took legal action because they soid the rights to Janus Films. They worked out a deal to release “Stories of a Bad Girl,” Babb’s version for five years, while Janus would release it for art audiences.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

The Rose, 1979, Mark Rydell

I have been aware of The Rose for most of my life. People had talked about it at various stages, but I made an unconscious decision not to see it. Why? Maybe because I loved Janis Joplin and disliked Bette Midler, so the burning desire wasn’t there. It wasn’t anything about Midler’s acting ability or talents, just that I was certainly not the target market for the remainder of her career. The fact that it was not really about Janis turned me off more than anything else. Having now seen it many years later, I’m actually glad I waited.

First off, this is not about Janis Joplin. In many of the supplements, this is stated and re-stated, and it is unfair to the film to get hung up on her life being the template for the plot. It is only the broad strokes that relate to Janis. This film is about the plight of the rock and roll star, the insatiable need for the rush of attention that one gets onstage, the insecurity off the stage, and the self-destruction in between. The only time that Janis is recollected is in the performances, yet not all of them. Most of the performances are all Bette channeling a 70s rock-starlet persona.

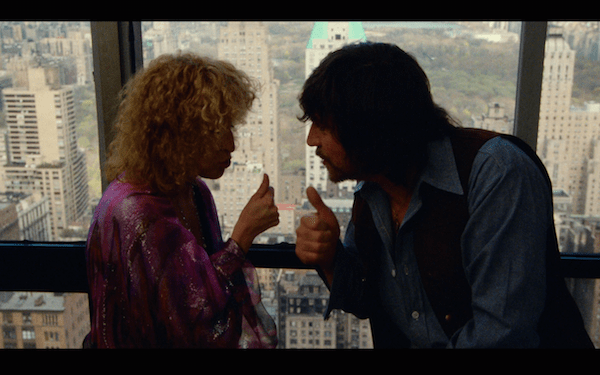

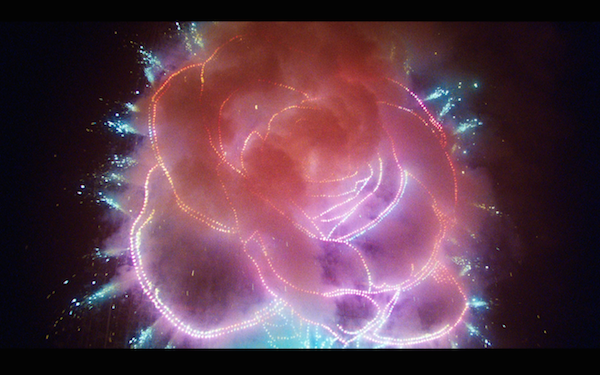

What stands out about the film is the cinematography. From the early scene in a building that towers above Central Park in New York City, to the kaleidoscope of images and colors that are captured in the live performance, every frame looks fantastic. Vilmos Zsigmond is responsible for the majority of the film’s appearance, but he also recruited some of the best in the industry to capture the concert sequences. Rather than go into specifics, I recommend you read Adam Batty’s post about The Eyes Behind The Rose.

The Rose shouts out at a concert that she keeps herself in shape through “Drugs, sex and rock n’ roll!” The order in which she places the words is telling. Most people refer to that era as “Sex, drugs and rock n’roll.” One of The Rose’s problems was that, despite her fame, she was not able to “get laid.” She expresses this directly in the early meeting with Rudge (Alan Bates). We don’t see her delve deeply into drugs until towards the end, which is what initiates her downfall, but the sex and subsequent rejection leads her to search for an escape. Rock n’ roll was last on her priority list because it really was. She was exhausted from all the touring and performing, and desperately wanted a break. Her mental stability was wearing down due to the lifestyle, yet Rudge trapped her. Her desire for the limelight and attention also trapped her. In many ways, rock n’ roll was her drug, only it was not giving her the same high it did before.

Deep down, The Rose simply wants to be appreciated. She’s shy, insecure, and in a lot of ways neurotic. The stage is the only place where she really belongs, where she feels appreciated. One recurring theme is her constant rejection. It begins with Billy Ray (Harry Dean Stanton) not so politely asking her not to sing his songs. Later in her hometown, she is recognized in a familiar shop owner in her hometown as Mary Rose and not “THE” Rose.

Redemption comes her way through Huston Dyer (Frederic Forrest), a limo driver who she steals from Billy Ray and takes on a wild misadventure of sex and shenanigans. Huston, however, is from a different world. He’s actually a deserter from the Army, and cannot relate to the “drugs, sex and rock n’ roll” lifestyle. What they have in common is that he is a deserter, and she wants to leave her rock career at least temporarily, and into his arms seems the most appropriate place to hide. Huston does not approve of what she’s doing to herself, and this comes to a head in the powerful bathhouse scene where he finally lets loose. He comes back to the fold, but the old magic has gone.

The Rose is a mess. “Do I look old?” she asks at one time. She is yearning for any sign of vitality, yet she finds none unless she is on-stage. The breaking point is when Rudge strong-arms her as a power contract ploy and cancels her hometown show. This smoking gun transforms her from a slow descent to a spiraling downfall. She takes solace in every chemical she can find, trying to find a chemically induced feeling that rivals what she feels onstage or in Huston’s arms. When some demons come back to haunt her, she finally caves, only it is too late. The damage has been done. That is the tragic reality of some rock n’ roll lifestyles. Again, even though this movie was not about Janis, her tragic reality is the backbone. The Rose’s downfall is just as tragic, even if fictional.

The performances are truly what makes the film worth watching. Midler owns her role as The Rose, and I was impressed that the star of Beaches was able to convincingly play a rock n’ roll star. Forrest as Huston also shines in the scenes where he gets to be the voice of reason. Even Alan Bates as Rudge does a fine job with what is essentially a flat character. Some of the dramatic choices are a stretch and at times the film gets heavy-handed, but overall it is a worthwhile character exploration.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements

Commentary: Mark Rydell from 2003.

- The band was put together with Rydell, Paul Rothchild, and Bette Midler. They were a real band that played real stories.

- This was NOT the Janis Joplin story as Rydell emphatically states. It was a character based on some of the rock stars in history. It was conceived as biography of her for years. They made a fictional character using the dramatic elements of Joplin’s life that were dramatic and fitting, and invented the rest.

- They shot real concerts, twice at two hours without interruption. There were no interruptions and Bette was really playing to the crowd. These shows were later cut together for the film.

- Bathhouse scene was unheard of. All that male nudity, even if not shown, was shocking for the time.

- Rydell spends a lot of time gushing about the actors. They all exceeded his expectations.

One thing I like about this commentary is that Rydell lets the film breathe. He stays out during important moments, so it’s almost as if watching the film again. He interjects only when he has something worth saying. Sometimes I prefer this sort of commentary to one with endless chatter.

Bette Midler: Interview from 2015.

At first she didn’t want to do it. She was a Joplin fan and didn’t want to tarnish her legacy, so they changed it from being inspired by Joplin and not telling the complete story. She started gymnastics for her stage moves. Wanted to get a panther quality to her moves, “a violent creature” on stage.

She praises Forrest in particular. She thought he did a great job at being patient. She wasn’t prepared for Harry Dean Stanton. He was tough. Everyone wanted her to succeed (except for Harry Dean.) They were supportive, and it was “joyful and full of love.” She remembers it more than most of her movies.

Mark Rydell: Interview in 2014.

He also didn’t want to do a straight Joplin biopic. People recommended Bette Midler and he knew she was perfect when he saw the dailies. She had sung in men’s bathhouses, so they incorporated it into the movie.

Aaron Russo was her manager and was very controlling. “You talk to me before you talk to Bette.” He called the police and got him out of there. Bette got him out of the way then and that began his relationship with Bette.

He talks at length about all the amazing Directors of Photography that he used for the concert footage. He needed nine cameras for these scenes. He asked Zsigmond to pick the best cameramen in town, and somehow he succeeded in getting the the giants of the era.

There were 6,000 people at the concert, who came out because of a radio announcement. They were told not to react unless the performer makes them react. She brought it. “That’s why the concert felt so alive, because they were alive.”

Vilmos Zsigmond: He speaks with cinematographer John Bailey in 2014.

The opening shot was in the Hilton in downtown NYC. It was difficult to light because they had to be careful of the backlighting in the windows.

Of course he also talks about the concert scenes. They lit them differently because they shot them on the same stage. They did the overhead helicopter shot, carefully lit it up, and did so to show the popularity and stature of The Rose. They did a lot of improvising with the shots because the performances were improvised. In addition to the star cinematographers, he also used Dave Myers, who was a big concert photographer, who famously shot Woodstock.

He thinks that the craft is diminishing, and that the concept of lighting is being lost. Too many people are becoming cinematographers. He is trying to teach the youngsters that are using digital cameras to go look at the old films, see how they are lit. Don’t get lazy by how easy the digital camera is to use.

Today Show: Tom Brokaw with Rydell and Midler in 1978.

It shows behind the scenes of them shooting the scene where she leaves a news conference, take after take. Brokaw interviews Rydell and he gives overwhelming praise to Midler for her performance.

Gene Shalit & Bette Midler: Interviews from 1979.

He asks the question about Janis Joplin, comparing the fact that Janis is 1960s whereas Bette is 1970s. Bette said that she did not intend to become Janis. She contrasts the differences. She is a New Yorker, which is a bombarding culture, but she played a Californian, which is more of a laid back atmosphere.

Janis Joplin, Tina Turner and Aretha Franklin inspired her. She saw them all in the same week in the 1960s and that was the turning point.

It is interesting hearing her reflect on her career, which is something she had just started thinking about recently. She says she would be happy if she retired tomorrow. Of course there were would be plenty more to come.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

Modern Times, 1936, Charles Chaplin

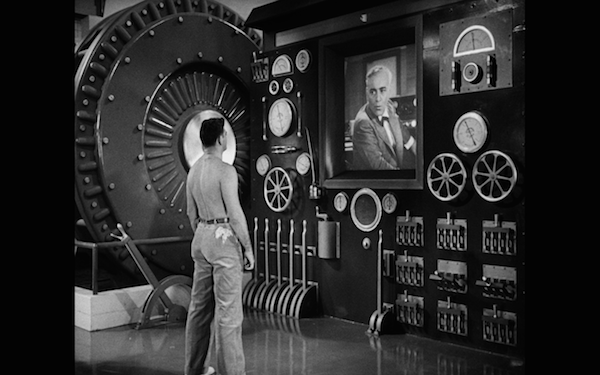

In many ways, Modern Times was both an ending and a beginning. For Chaplin, it was the end of his silent movie star career and his popular character, the tramp. It was also the last major silent film release. It was at the height of the depression, and the underlying themes represented Chaplin’s critical feelings of industry and the exploitation of the working man. Little could he know that everything would change in a few years with a war, which would devastate the world and end the depression. Yet, the changing times did not date the picture. With historical perspective, Modern Times can be seen as a nostalgic and sentimental transitional film.

If there are any questions about Chaplin’s thoughts about industrialization, then they are answered within the first 15 minutes. Chaplin effective turns a social issue (one that we felt strongly above) into comedy, and as expected, he was completely successful. The early factory scene delivers the laughs. Chaplin becomes both obsessed and complacent with the act of riveting. Occasionally he’ll sneeze or otherwise be forced to miss an item and the assembly line will go out of whack, forcing the two other employees working behind him to get frustrated with his antics. The Tramp keeps on turning knobs with his two wrenches, sometimes even when his hands are not over the assembly line. He gets distracted by a woman’s attire with dark, loud buttons, and tries to turn them too. This scene works flawlessly. There are not many cuts, so the action must have been carefully rehearsed and difficult to carry out, and the speed at which the scene flows thanks to the customary 16 frames per second in silent films make it seem all the more hurried and manic.

The scene with the most laughs, at least for me, is the lunch efficiency machine. Again, Chaplin is poking fun of industrialization, specifically the fact that they value production so highly that they will compromise the worker’s free time and convenience by automating their lunch process. The machine dumps soup on Chaplin, forces him to eat corn on the cob at a rapid fire pace, and smacks him on the face when it is intended to merely wipe his chin. The device itself is funny simply due to its absurdity, but it is Chaplin’s performance that cements the scene as being so memorable in his cannon. He recalls the lunch machine later in the film by becoming a lunch machine himself, yet he is just as effective (or ineffective) as the automated version. Again, this is funny, but he is still making a cultural statement. People do not need external assistance, whether from a machine or a human, to perform basic duties.

Chaplin’s politics seem clear in some instances and hazy in others. He is clearly portraying modernity from a leftist perspective, and that echoes some of the activism he was undertaking outside of the film industry. However, he was careful not to go too far to the left. There is another scene where he takes a flag from a truck. A communist mob marches behind him, and he is swept up with them. As the flag waver in the front, he is mistaken as the front-runner in yet another hilarious gag. Despite the scene’s humor, he is distancing himself from the Communist movement. He was leftist, but not that left wing.

Unlike other Chaplin pictures, in Modern Times he has a co-star – a trampette if you will – in the form of Paulette Goddard, his off-screen lover. Even though Chaplin is always the funniest, she provides a welcome equilibrium to his antics, along with a motivation for him to pursue his character arc. Before meeting her, he was perfectly content being in jail because, after all, they served food and gave him a roof over his head, which wasn’t always the case on the outside (and this was another comment about modern times.) After meeting Goddard as The Gamin, he wants to succumb to the lures of society. He wants a good job so that he can afford a nice house, even if his dream house still rejects modernity by extracting milk directly from a passing cow rather than buy the processed product.

As Chaplin and Goddard pursue normal lives, and even find themselves living in a crude, fragile shack, they cling more to a life of poverty. In Chaplin’s vision, having less allows one to live in opposition to the modern trappings of society. They find themselves in plenty of other comic scenes, including a department store and most famously, a restaurant where Chaplin sings for the first time, but this is not the life for them. As everything they aim for falls apart, they are content simply walking away, hand in hand, comfortable in each other’s company.

Film Rating: 9.5

Supplements

Commentary:

- Modern Times definitively identifies Chaplin’s transition from silent films into sound. He had intentions of making a talkie and even wrote a script, but trashed the idea after filming a couple scenes.

- After City Lights, he went on an 18-month world tour where he was treated as a celebrity. He saw economic collapse and nationalism. He published a number of social articles when he returned, including those about the tyranny of the assembly line.

- The lunch machine scene took 7 days. It isn’t known for sure because Chaplin never revealed his methods, but it is thought that there was an operator somewhere, although stills show Chaplin operating the lever.

- He was accused of ripping off Rene Clair’s À Nous la Liberté. Some argued that the similarities were obvious with any industrial story. Clair was not pleased with the lawsuit because he respected Chaplin. He didn’t think Chaplin was guilty, and if so, was flattered. The suit was out of Clair’s hands and went on. It didn’t resolve until 1947, where Chaplin paid a modest settlement.

- Goddard had been a struggling actress and a divorcee when she met Chaplin, when their affair and collaboration began. He convinced her to go back to her natural brunette color instead of the platinum blonde.

- One of the few critical complaints is that Modern Times is a series of 2-reelers, which is true to an extent (factory, furniture store, factory again, restaurant).

- Like City Lights, he was credited as composer. People have criticized him for taking too much credit away from his arrangers. He could play instruments, but could not read music. The arrangers all confirmed that he directed the compositions through them.

- The FBI, trying to establish a link with him and the Communist Party, investigated Chaplin. It was more that he found left leaning individuals to be better dinner companions. The FBI never found anything despite their pursuits. He was never tied to the party, so their efforts were futile.

- Chaplin’s song became famous. In 1939 it was released as a song about who had the better mustache, Chaplin or Hitler. It was most famous as being the first time his voice is heard on screen. He sings a gibberish of his own invention.

Modern Times: A Closer Look: Visual essay from Chaplin historian Jeffrey Vance.

Chaplin was highly secretive about how he worked. He did not allow people to film him during the process. “If people know how it’s done, the magic is gone.” Still photos survive as the background of the making of Modern Times.

He spoke with great minds (Churchill, Einstein, others), and wanted to make some sort of social cinema. He nixed the idea of a Napoleon film when he befriended Paulette Goddard. This would begin an 8-year collaboration with Chaplin and Goddard, which included a common law marriage. They treated each other as equals, and he cast her in that manner in the film.

The film was steeped in the political and social realities of the time. He met Henry Ford in 1923 and found that people who were hired from farms to factories often had nervous breakdowns.

Goddard later called it her favorite film. “Charlie could be difficult at times, but charming” and he gave her valued education and experience. Their collaboration would end due to a falling out after The Great Dictator.

A Bucket of Water and a Glass Matte: Craig Baron and Ben Burtt talk about visual and sound effects.

Chaplin isn’t thought of in terms of visual effects, but he used them effectively. He was a visual director because of his roots in silent film. He used techniques like miniatures, rear projection, glass shots, matte paintings, and many more. He built large sets, like he did with the factory. He used a lot of hanging miniatures, even during the factory sequence. They are smaller, yet they give the impression of appearing full-size, and they make the set look larger.

Sounds were used as needed for dramatic or comic effect, but no more. He preferred to use them only when necessary, such as the feeding machine and flatulence jokes.

They show the roller skating shot in detail. Chaplin used a glass matte painting shot. Camera shoots through a sheet of glass with a painting. The empty “cliff” is the painting. Chaplin was an exception skater, but was never in any danger.

Silent Traces: Modern Times: Visual essay with John Bengtson as he tours the locations that Chaplin used.

Chaplin began in Los Angeles, and many of the locations still exist today. He filmed factory scenes near gas storage tanks. The north of which was demolished in 1973. The landmark also appears in The Kid, Buster Keaton’s The Goat. The southern plant was smaller and used in the worker lineup scene.

Today the Chaplin studio in Hollywood is home to Jim Henson company, where Kermit pays tribute to Chaplin by dressing as the tramp.

David Raksin and the Score: 1992 interview with the composer for the film..

Alfred Newman did the conducting and was brilliant. Raksin was credited as music arranger. Charlie was autocratic, not used to people disagreeing with him. Initially he did not get along with Raksin because his taste and authority were challenged. Raksin was at one point fired due to these disagreements. Later Newman was looking at his Raskin’s sketches and thought they were marvelous, and he talked Charlie out of firing him. Charlie and David had to talk privately and work things out before he could come back.

Charlie did not know how to develop music, but he was excellent at working it out with someone who knew about music. He had an understanding of instruments that most non-musicians wouldn’t have. Raskin would generally like what Chaplin did, and prior disagreement were his just acting out of instinct.

Two Bits: These are two deleted scenes.

Crossing the Street – Funny scene with the tramp not understanding the stop and go signs, and the cop chiding him along. Even though it is funny, it does not fit too well with the theme of the film. I understand why it was cut.

The Tramp’s Song, unedited. – The last verse was removed when Chaplin re-edited the film. This 4-minute full sequence restores it. The last verse doesn’t add much and I expect he cut it for brevity.

All At Sea: This is a short filmed by Alistair Cooke of a yacht trip with Chaplin and Goddard with an added film score.

We see their mugs playing to the camera. Mostly it is Charlie doing the comic antics, but we also see Alistair showing a sense of humor that would surprise most fans of Masterpiece Theater.

It is strange seeing Chaplin out of his element, dressed well with perfectly combed hair. He looks just like a wealthy man on a yacht and nothing like the tramp. That doesn’t mean he isn’t funny. He does a series of routines with a broom, impersonating people that were in the headlines such as Gaynor, Garbo, and Harlow.

This documentary really is a treasure and I’m glad they added it to the disc.

Susan Cooke Kittredge Interview: When her father died in 2004, she was responsible for sorting through his old belongings. She found a treasure trove. Behind everything was a reel of film labeled “Chaplin film.” He had told his children that he had made a film with Chaplin, but they thought he was making it up. Cooke thought had he lost it, and it was unfortunate that it was found after his passing.

Cooke wanted to be a film critic early. He approached Chaplin and told him he was with the London Observer and asked to schedule an interview. Chaplin says yes, and Cooke pitched it to the Observer to get them to hire him. They hit it off well, and the interview turned to lunch and then dinner, and then they became inseparable.

They spent the weekend cruising around Catalina Island. Cooke happened to have a 8mm camera so they just thought they would shoot a film. It was just something to do.

Their friendship did not continue because their careers went in different directions. They saw each other occasionally and would reminisce, but the intensity of the friendship passed.

The Rink: – This has plenty of slapstick comedy and subtle gags. Some jumped out at me, like when he is working at a restaurant and tells his boss,“I’m going to lunch,” and promptly leaves the restaurant. The antics in the skating rink make it a fitting companion to Modern Times. This short shows off Chaplin’s skating ability, which was quite impressive.

For the First Time: 1967 Cuban documentary about showing motion pictures to rural communities that haven’t ever seen a movie. They showed Modern Times.

This was my second favorite supplement on the disc, with the Cooke film as the first.

The crew traveled to rural areas near Guantanamo and Baracoa. Many peasants had never seen a movie.

There is ecstatic laughter at the lunch scene! When the corncob goes in his mouth, people seem about to lose themselves with joy. Some kids yawn and then fall asleep. Some people are so blown away by what they are seeing that you can see tears in their eyes. My only complaint is that they don’t have interviews afterward to hear their thoughts.

Chaplin Today: “Modern Times.”: Philippe Truffaut documentary in 2003 with the Dardenne brothers.

The famous filmmakers dissect the film. They identify that he uses hunger in most of his films, and bread brings him together with the girl and is a prop in prison. Even the furniture store “burglars” are only looking for some food.

The assembly lines of Ford’s auto plants were mechanized labor, and during the depression that was no hiring because there was no demand for product. Chaplin was inspired by the assembly lines in Detroit to make the movie. Dardennes: “Man becomes a cog in the machine.” Chaplin sabotages the system, which is the ultimate rebellion. Dardennes talk about how when he does his ballet, he distracts the men from the machine, but they are still chained to it and resume work when he reminds them.

Criterion Rating: 10/10

New York Postscript

Yesterday’s post about my Criterion trip was lengthy enough, but I forgot one tidbit.

Remember I was wearing the Ride t-shirt and the show had been the night before? After I left the Criterion offices, I got into an elevator with a number of people. I was pretty much in a daze, reflecting on the Criterion experience, that I barely even noticed them. As I walked out of the building, someone in front of me held the door open. As I passed through, he noticed my shirt.

Coincidentally, I got the same question that the Criterion guys asked. “Were you at the show last night?”

This guy was probably about 10 years older than the Criterion Ride fan, and maybe a few years younger than myself. He was dressed in business casual, but I could see some stubble on his face. Today wasn’t a shaving day. Of course I answered yes with enthusiasm. As it turned out, he had been to the show as well, which is why he looked slightly worn out. We talked for a few moments about the highlights of the show.

I was standing there with the Criterion postcards in my hand, which he then noticed. He didn’t say anything, just looked back at me. Without thinking, I asked, “do you work at Criterion?” He laughed. “I wish! I just work upstairs.” He didn’t go into more detail about his job, and I’m guessing it didn’t measure up to Criterion. We then started talking about Criterion and he learned that I was just visiting their office as a fan.

He then told me some stories about just working in the building with them. He said he sees artist-types all the time, which I am guessing are sometimes directors, sometimes graphic designers, or other people associated with the industry. I could tell that while he enjoyed film, he wasn’t the foreign film devotee that I am, and wouldn’t recognize a lot of avant-garde directors, so I could not glean any secrets from him. The only guest he had ever recognized was Wes Anderson, who he had seen numerous times. That makes sense because W.A. has a distinctive look, and is arguably the biggest and most recognized American indie-auteur.

With Moonrise Kingdom‘s postponed release just around the corner, I could have pressed hm for more details. I didn’t ask when the visits took place or how long he had been working there. Anderson probably visited plenty for The Fantastic Mr. Fox and The Life Aquatic because of supplements and to sign off on the releases so they could use the ‘Director Approved’ sticker. So while the news wasn’t revolutionary, it was still interesting to hear the firsthand experiences from someone who works a few floors above Criterion.

When I go on a vacation, I make it a point to pack a few movies. This time I packed four Criterion discs. Guess how many I watched? Absolutely none. I watched a light classic movie on the plane, and that was it. That speaks to the fact that we had such a packed trip. After doing the podcast, seeing a concert and visiting Criterion, I was just either too excited or too exhausted to pour my energy and concentration into an art film.

I happened to have completed Modern Times and all of its supplements before leaving town, and was hoping to finish writing my post on the airplane or in the hotel. That didn’t happen either. I tried a few times, but found my idle time too distracted with twitter, email, or whatever.

Since I have this mammoth ongoing project in process, I sometimes felt guilty for neglecting my ‘responsibilities.’ As fate would have it, we were in a restaurant yesterday and they were playing Chaplin films. Great idea!

We watched and laughed at a silent Chaplin as we ate, which ended about the time we were paying our check. As you can see from the image above, the next movie was Modern Times. We left right after I took the above picture, but I found it an eerily coincidental reminder. Expect that post up within the next couple of days as I get re-settled into town.

The guys over at CriterionForum found a phantom page for Samantha Fuller. Could this mean that Pickup on South Street is going to be reissued on Criterion? Could this mean that another Fuller title is forthcoming? Maybe a box-set? The sleuths at CriterionForum have concluded that this is indeed for Pickup. I hope they are right. What James brought up about Sam Fuller on the podcast was fascinating and I would love to learn more about the man, and of course I’d be eager to revisit this restored classic again from my home theater. My guess is we’ll know something in a few weeks or months.

A Trip to Criterion (and other NYC cultural excursions)

It was Day 3 on our NYC “not a tour” trip. Day 1 was a movie — Pickup on South Street; day 2 was a concert — Ride; Day 3 was shopping and just hanging about. The one thing about New York City is there’s so much to see and do, that it caters to everyone’s interests, so we ended up focusing on culture, cinema and art. We spent some time at a Game of Thrones store (!), near MoMa looking at Russian Constructivist artwork, and ended with me making a beeline to Criterion Collection Headquarters. Since the latter trip is what is most interesting to readers here, I’ll start with that and work my way backwards. This is like the Memento of blog posts.

Disclaimer: Please do not try this without contacting Criterion. They are super friendly as I found out, but this is a place of business and they probably don’t want hordes of people dropping by.

It was getting toward the end of the day. We had already walked for miles, shopped at the places we wanted to shop, and were a little bit travel weary. We decided to head back to the hotel. My wife wanted to get in a nap before our dinner reservation.

We were walking on 5th Avenue, which has a mixture of upscale retail, commercial and tourism. We passed CBS without interest, but that prompted the thought – where in New York City would I like to go that would connect with my film interests? It hit me like a bolt of lightning. THE CRITERION COLLECTION.

As we walked, I became one of the people that annoy me – the phone walker. I was using Maps and the Internet to try to figure out where in the city their office is. As luck would have it, Criterion was not far from our hotel, only it was on the opposite side of a big landmark. There was no way I was going to talk my wife into going with me. I looked at the clock and it was still during the business day on a Friday, but with us leaving town on Sunday, this was the only opportunity. My wife laughed when I told her my plan, but it was to split up at the crossroads. She would head to the right to the hotel, while I would head left and try to find Criterion. It was about a mile of a walk out of our way.

The office was hard to find. There is no large sign out that says ‘Criterion Collection.’ I had an address, but it is not really easy to see street numbers. At first I passed it by a couple blocks, still looking for it on the left. The Internet helped again, and I was able to narrow down the building they were in. Eventually I found it, and it was just that, an office building that looks like the thousand other New York buildings.

As I walked in, I looked at the directory on the right to see if Criterion was listed. Nope. Was this the right place? I walked in further. There were two security guards at the very front. I work in an office at home, but realized that I was wearing a concert shirt, had gone three days without shaving, and had been walking all over the city in the rain. They were professional, but wanted to know where I was visiting. I cleared my throat. “The Criterion Collection,” I said, probably with a waver in my voice, expecting them to say “The What??” Instead they responded with “name and ID please.” They didn’t even do a double take about my appearance. It then dawned on me that I was visiting an office that gets tons of artists. I was probably dressed more appropriately than I thought.

Once past the first barrier, I was in the building and had to figure out where the office was. There were about 20 floors. I went into an elevator with a group of businessmen. I guessed at the floor (correctly, I would find), and they all looked at me curiously. I would find out why later.

As I got off the elevator, it was there before me. It looked like any ordinary office with a reception area, transparent glass walls and doors. There was no large Criterion sign, but there was a distinctive feature. There were movie posters, all over the place. From the elevator I could only see Belle de Jour, and as I got closer, there were many more. They were all over the place. I had found my Mecca.

I walked in and to my right, saw a young gentleman who looked at me curiously. I could tell they were not used to visitors. Again, my nerves shot up and was expecting to be escorted back to the door. Instead I just told them the truth. “Hey there, this may seem weird, but I am just a major fan of your products. I own a ton of them and follow you religiously. I just wanted to swing by, say hello and thanks.” Again, I braced myself, but was relieved when I was not turned away.

As I mentioned above, I had seen a concert the night before and was wearing the shirt. Ride is an obscure art-rock band, technically categorized as “shoegaze”, but not a band that the masses would know. The young man, essentially acting as receptionist, said hello. Seeing my shirt, he asked if I was at the show last night. That broke the ice. Yes, and it was amazing. We talked about that shortly, so it was nice to have common ground. He had not been able to make it to the show, but was clearly a fan.

I was looking around and still wary of being thrown out. Aside from the posters, this looked like any other office. There was a waiting room with comfortable couches and coffee table books (one of which was Criterion Designs, naturally). There were fax machines, copiers, files, and that sort of thing.

There were two people up front, the Ride fan and a still-young, but slightly older lady behind him performing various office functions. As we would talk, she would occasionally look back and beam a smile, usually when I made some sort of film reference.

They were welcoming and invited me to take pictures of the posters and reception area. Still nervous, I took pictures, but I did quick takes shots from my phone rather than lining them up perfectly to get everything in the frame. I guess if I had done the latter, I would have been right at home.

We started talking. “Are you film buffs, or do you just work here?” was my first question, and it really was a dumb one. “We work here, but we are film buffs, and that’s why we work here.” Great answer! Thousands of people would dream of working at Criterion, and even though I have a terrific job back at home, I’m one of them.

We then began to talk shop. He knew the city, the film industry, and could hold his own talking with a film geek. He asked me questions, and I told him about myself and how I appreciate Criterion. Yes, I did mention the blog and how I follow podcasts (like CriterionCast), but did not give a lot of specifics. I didn’t get too nosy asking about their roles or what they do. To stay in their good graces, I didn’t want to make this an interview with question after question. It was a pleasant chat.

As I was venturing further in to take pictures, I was cut off at one point. “You can only stay within this general area,” he said, pleasantly and not authoritatively. “Besides, there’s really nothing to see back there, just offices.” Oh, there would be plenty for me to see. I’d want to look at every file, in every office drawer, and especially on every computer monitor. Of course I obeyed.

The coolest thing was when he asked if I wanted my picture taken. Yes! I was looking disheveled, as you can see below, and the cane is for walking in New York after recovering from a surgery. It helps. I asked to have it taken right between the posters for The Killing and Modern Times, because the latter is the one I am working on now. As it turns out I blocked both pictures, but that’s fine. It came out okay.

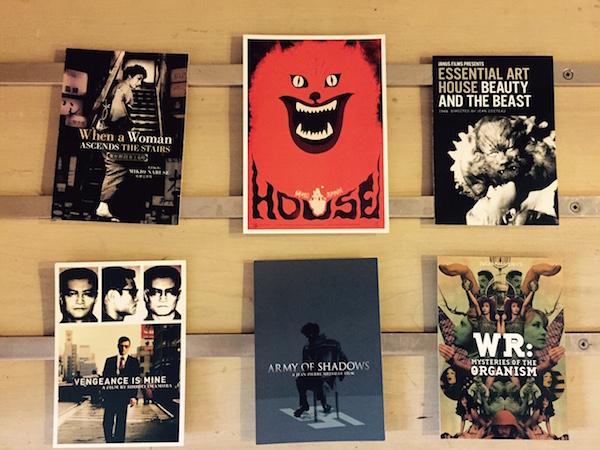

They had a cabinet of postcards and offered to let me take any. I took a select few, and could have taken each and every one. Again, I didn’t want to wear out my welcome.

I asked if people like me show up. Occasionally, they said. Not daily, and I got the impression that it may not even be weekly. “But we know we have our fans,” they said.

A good 15-minutes had passed and I figured I had distracted them long enough. They were doing their jobs after all, and they were more than hospitable to me. They were great, just the type of people I’d love to grab a drink with and talk films.

I had one last request as I left. “Can you pass along to the suggestion people a request?” They smiled. They were glad to, eager to hear what I would come up with. I asked for La Chienne from Jean Renoir. Big smile. “You got it. I will pass that along.” This was another reference that caused the lady to turn around and she again beamed a big smile. They may have reacted accordingly because I recommended a Jean Renoir, who is obviously a favorite of the label, but it is not going to get the sales of a Beatles or David Lynch movie. I also know there is a 4k restoration out there somewhere. Did those smiles mean that it was already in the works, and they were just imagining a positive reaction on the 15th of some month? Your guess is as good as mine, but I am cautiously optimistic.

As for the other topics that we discussed, I’m going to remain silent. They did say some things that I could interpret as being a sign of things to come; yet they did not give away any secrets. That said, I left there having gleaned what might have been secrets. These could have been red herrings or perhaps I’m reading into things out of my own enthusiasm. Either way, out of respect to the label and their veil of secrecy (and since they have my name and picture,) I’m going to keep those inferences to myself until they are announced. I’d rather stay in Criterion’s good graces. I will say that if my guesses are correct, there will be some happy people out there.

My visit to Criterion was not the only cool film and media place I visited that day.