Category Archives: Film

Secret of the Grain, 2007, Abdellatif Kechiche

Before I go too far with this write-up, indulge me to complain about the title. The title itself is not terrible. The problem is it does not represent the film well. The French title is La graine et le mulet, which if you ask Google Translate, it will tell you this says “Grain and mule.” Of course this isn’t the real title. The “mulet” is also the French word for the fish that we call “mullet”. The title is clever because it is a play on words. The protagonist is an older, stubborn man (like a mule), and the recurring food dish served, couscous, is comprised of grain and mullet fish. The international title is just Couscous, which is more of a literal translation if you take the double meaning out. In fairness, the French pun cannot be replicated. My guess is a title like Couscous wouldn’t sell well in America, hence the title of this disc. I like the international title, so that’s how I’ll refer to it throughout the essay.

Next I want to say a few words about Abdellatif Kechiche. He is a Tunisian-French filmmaker, and the subjects of his films are of the lower classes, especially this film, which hardly has any strictly French people that aren’t bureaucrats (there is one white French dockworker). After this film came out, Paris Match called him the French Ken Loach. The article I linked is in French, but you can find Mister Loach in the second paragraph. Since then he has made two features, Black Venus about a black South African, and the Cannes champion, Blue is the Warmest Color, which is about a young lesbian couple. Even for France, where we more frequently see the point of view of lower class characters, these films focus on fringe groups. On top of that, he shoots with hand-held, shaky cam, with extreme close-ups, and with lots of dialogue. I’d say the comparison is appropriate. After seeing his two films on Criterion, I’m intrigued and want to see the rest of his work, plus what he does next. Hopefully, like Loach, he’ll be able to continue making films his way.

Of the two Kechiche films I’ve seen, with all due respect to the Cannes winner, Couscous won my heart. It is an existential tale of a flawed, aging family man, who finds himself on the outs working at the boatyard. He’s faced with the prospect of losing hours and not being able to pay his bills, or finding other work. As a Tunisian immigrant, work isn’t easy to come by. In time he hatches a plan to build a restaurant on a boat serving the legendary dish of couscous that his ex-wife prepares. He has a few children with that ex-wife, and his current lover has a teenage daughter, Rym, who he treats as if she were his own. She helps him navigate the byzantine bureaucratic waters in the hopes of setting the project afloat.

A technique of Kechiche’s is long scenes. I remember several in Blue is the Warmest Color (including one controversial one), and there are even more in Couscous. The most notable is a lengthy Sunday dinner scene with all of the family and friends. This is the weekly event where Slimane’s ex-wife, Souad, makes her trademark couscous dish. The scene goes on forever, but it is a truly joyous occasion. The camerawork is frenetic, again with heavy shaky came and constant close-ups. You can even see the grain in the actor’s mouths. No doubt they were really eating. The movement is so fluid that I failed to get a decent screen of the entire scene. It just moved too quickly and chaotically. Even if the scene goes on awhile and few plot details occur, it is one of my favorite scenes in the film. It establishes the tight bond of family and the deliciousness of the food. “Couscous is love,” as they say. Indeed.

It also shows the world of exile. Slimane benefits from the couscous dinner, but he is not a participant at the celebratory event. He eats his dish alone at first until he is joined by his unofficially adopted daughter, Rym (Hafsia Herzi). He is a man that does not belong, and only barely belongs in the world of his lover. He is somewhat discrete about that world, and as we find out later, he keeps his real family separate from the adopted family.

Is Slimane a good man? That’s not an easy question. He is unquestionably devoted to his children and his grandchildren. He has a close relationship with his sons and daughters, and even recruits them into helping with his restaurant venture. Ultimately he is doing this for them, not for him. His life has been spent, perhaps wasted, but they hopefully have a future in a world that doesn’t always welcome them. He also has a close relationship with Rym, who is not his natural daughter and he has no obligation to her, and she reciprocates, seeing him as a father figure that she wants to help.

Slimane may have some admirable qualities, but he has clearly made mistakes in life. We do not understand what happened to break up his marriage, but if his son is any indication, it was infidelity, perhaps with his current lover. His son, Majid, is a philanderer, and in the opening scene we see him in the midst of an affair with an older woman. We later see the justified suspicions of Majid’s wife Julia in an uncomfortably powerful emotional tirade. Perhaps Slimane acted similarly, and perhaps Majid learned his lack of fidelity from his father. Since Majid’s actions later are a turning point of the plot and Slimane’s fate, you could argue that Slimane set his own table.

Some of the remainder of this post could be considered spoiler territory. I do not think so, but be warned in case you want to experience the final act on your own. I will not spoil major plot points or the ending, although I’ll say that it’s an interesting ending that is worth discussing.

I’m going to mostly steer clear of the French bureaucracy and the social statement of the film, which is basically that the chips are stacked against Arab-Franco citizens. It recalls Kassowitz’s La Haine to a certain degree, only it is a family drama rather than a tale of exiled, childhood rebellion. Slimane’s family may not be happy with their status, but they are not rebellious. If anything they are disillusioned and naïve that a prejudiced society would give them a fair shot. As a way to prove to the people that the couscous is delicious and that Slimane can handle the pressure, they host a gala on a boat with all of the local, French dignitaries invited.

The most memorable scene for a lot of reasons is Rym’s belly dance. Many will find it electrifying; others will find it tantalizing; some might even find it disgusting. Whatever your take, there is no doubt that it is a bold performance from Hafsia Herzi. It also comes at a time in the plot and in the narrative that things are slowing down and there seems a lack of momentum. It also is a bridge to the ending. Rym is the specimen of energy and vitality. She has proven through her efforts to help with Slimane’s business that she is wise beyond her years and ambitious. She has a bright future. Without her, the party would have never happened. Slimane is not Rym. He is slower and cannot keep up, but that does not mean he will not try.

https://twitter.com/awest505/status/623249780651765760

Film Rating: 8.5/10

Supplements

Abdellatif Kechiche: 2010 interview.

He admits that his films are not accessible. He avoids known formats, and that might even be bothersome for those who want entertainment. His films are “forms of perception” of different aspects of life.

His father was an inspiration for the film. He wanted his father to star in the film, but he died in pre-production. He wanted to film the working class because that’s what he knows and is what motivates him.

He wanted to shoot in Nice, where he grew up. But when his father died he wanted to change the location to change in order to change the memories. He settled on Sète and used many non-actors from the area.

Sueur:

Kechiche introduces what is a 45-minute short of the belly dance in the film. He says that he really likes sweat and a lot of sweat goes into the performance. He pulled deleted sequences along with what ended up in the final cut, and used them to make a short film of just the dance.

The dance itself is mostly like the filmed version. There are some of the same scenes, including the memorable beginning. At times she sings; at others she chants. We get to see the crowd more engaged. The scene is allowed to breathe more than in the film because the film is so tightly edited.

20 Heures: Excerpt from 2008 TV program.

This is an interview news program and they have Kechiche and Hafsia Herzi on the panel. They go to a location feed at Sète where they interview many of the locals who were non-actors and crew. They are all happy about the acclaim, the awards and the attention. Kechiche says that Sète had energy that was crucial to the film. Herzi had not acted before, but she won the Cesar and was of course pleased.

Ludovic Cortade: Film scholar interview about the themes.

The film is about what is called the “Beur” community, which is a French word for Arabs. The film addresses identity, exile, immigration, and many other ethnic diversity themes. He does not think of this as a “Beur” film, but it does deal with several of these elements. One is racism, mostly from the bureaucrats. Another is exile, like when Slimane is reminded of his upbringing. In most traditional “Beur” films, the men are prominent (like La Haine), but in Secret of the Grain, women are prominent.

The real city of Sète has a variety of types of locations, including beautiful seascapes and Mt. Saint Claire, which is a landmark that has rich housing. There is meaning in what is shown and not shown. We see poorer areas through Kechiche’s lens, such as the docks and lower cost housing. We do not see gentrified or tourist areas.

Hafsia Herzi: Interview with the actress who plays Rym.

She had no contadts in the industry because she lived in Marseilles and there is not much of an industry there. This was her first real audition. She embellished a passion for Eastern dance on her resume, but it probably helped land her the job. Everything went fast, but Kechiche liked her performance. Her scenes had been cut, but when he saw her ability, he rewrote her back in.

She talks about the dancing scene. It was tough with her dancing in front of all those people, and that was no illusion. She was dancing in front of a huge crowd. She wouldn’t have been able to do it anywhere off the set. She wouldn’t have had the nerves. She thought of it as a performance on stage and that fueled her.

Bouraouïa Marzouk: Interview with the actress that played Souad.

She was an immigrant and came to Paris with a thirst of knowledge and energy. She learned to speak French at the Yugoslavian Cultural Center. She got an education, any degrees, made an income, had kids, etc.

The character was not like her with all her books, but she put her all into the role and tried to play her as hard working. They rehearsed the Sunday lunch scene for 10-15 days. She really made the couscous and they really ate it. This was not movie fakery.

Musicians: Interview with the musicians from the film.

Hamid plays lute as a hobby, not professional, but it is his life’s passion. He cannot live without it. Idwar is a flutist that Hamid found. Salah plays zither, which his father taught him in Egypt. He started playing professionally in 1958.

One member had film experience, and said that some directors are very intense, “like Gods” he said. All of the musicians speak flatteringly about Kechiche. They say he was very calm on the set, very respectful and patient. “He creates actors,” one of them said.

They talk about the belly-dancing scene. Without a doubt they agreed that Hafsia is a star. They were not paying as much attention to the dance while they were playing because they were focusing on the music. When they saw it on the screen, and this quote requires no translation, “oof, lalala!” They say she worked extremely hard, was very committed.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

The Bridge, 1959, Bernhard Wicki

Anti-war films are not easy to pull off. Some of the best of them, like Rossellini’s War Trilogy, Battle of Algiers and even the American Best Years of our Lives are so effective because they were produced shortly after the end of the war. The wounds are personal and fresh. The pain is evident in all of these examples. Sure, there is a long list of fantastic war films to come out years after the war, although many of those use prior wars as analogies to current conflicts, but there are many more misfires (pun intended). The first two examples I gave above were shot in neorealistic style, and the third could be argued to be as close to neorealism that a film could get during the Hollywood studio system. The Bridge was also in the neorealistic style, but it was produced fifteen years after the war was over.

Germany is different. Nazism had dominated society up until the war, and Third Reich fascist rhetoric (or propaganda) had become adopted by the entire country. Nazism was celebrated, as many cinephiles have seen in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. The ending of the war and Nazism forever altered German society, and the manner of thinking needed time to change. Berlin was occupied for a long time, and eventually the nation was split during the Cold War. Even though there were forward thinkers in West Germany, many of the older generations still clung onto vestiges of Nazism and German heroism. As I learned in the supplements for this disc, there were German war films being made prior to The Bridge, but they were often celebrating German heroism. They may not have been completely pro-war, but they certainly were not decidedly anti-war as Wicki’s film would be.

Keep in mind that I will spoil major plot points and the ending of the film. Read and look at the images at your own risk.

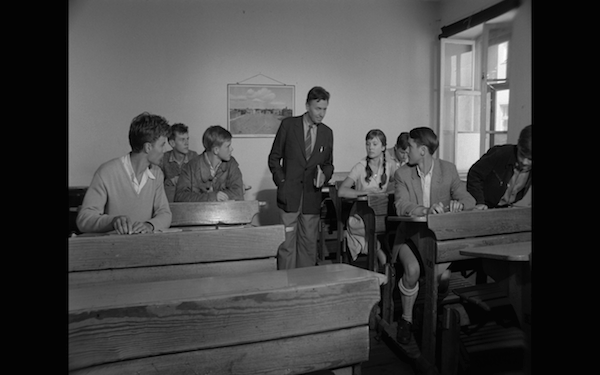

The first two acts of the film are primarily spent on exposition, establishing the foundation of the children as they are drafted, their families, school, lovers, and so on. Even the scenes as they enter the military are mostly expositional, as we are still learning the circumstances of the war, the motives of those in command, and the feelings of the children as they enter this frightening chapter of their lives.

The film also incorporates many locations early in the film that will come into play later. The most notable of these is the actual bridge. We get to see the bridge as it would normally be used, as a center of the town that citizens use as a walkway and meeting point. During the early scenes, it is portrayed as an area of peace. Even when a bomb is dropped and misses the bridge, people are hardly fearful of it. The children even make jokes about.

Thus far, much of the early response to this Criterion release seems to be positive, but one individual whose opinion I respect was not singing the same tune. While he enjoyed the last third, he took exception with the first two acts, finding them dull and uninteresting. He also compared it unfavorably to All Quiet on the Western Front, which also came to my mind. There are so many parallels that I think the filmmakers must have had Remarque’s book or Milestone’s film in mind. Ths friend makes valid points and I appreciate his critical thinking, and in some ways I agree, but my take is different.

The heavy exposition is used to show the generational gap between the children and the adults. We have to remember that they had all been indoctrinated into the Nazi system, but on different levels. The children are still naïve about the world. Many of them had been in the Nazi youth and had learned the propaganda about honoring and protecting their fatherland in school and elsewhere. The kids may all have different personality types and upbringing – wild and rebellious or tame and obedient, lower class or upper class – but they all share the same feelings about bravery and patriotism. Even if they are fearful and apprehensive about leaving their homes, getting their draft cards is not disappointing. Many of them are excited by the prospect of going to war and fighting like adults, without realizing the grim realities that would follow. They are innocent. They are dumb. They are just kids.

The adults, on the other hand, are not so naïve and innocent. While they all undoubtedly love and care for their children in their own way, they are all imperfect and corrupted in some capacity. One family is broken because of what appears to be marital infidelity. One of the upper class fathers has bought into the Nazi system to the extent that he benefits from the party. This is one of the most powerful of the early scenes, as the son throws this privileged position in his face, lashing out at him for being a disgrace. The father retorts by reminding his child how the military is about to break him. He calls his child a “snotty brat,” and says, “they’ll make a man out of you.” The child gets the last word, “a man like you?” The kids, however invested in the system, are aware of the decadence that comes with age.

A reoccurring theme that follows the film along at every stage is the fact that children are being sent to war. One of the fathers laments that the children “belong in kindergarten, not the barracks.” The child takes the meaning as an insult to his masculinity, and the use of the word ‘kindergarten’ will come back later in the story. Everyone knows that they are in the last throes of the war, and they are ashamed that children are being thrown out there as pawns as an act of futility. The school teacher approaches the military Captain, trying to reason with him to not use these children as cannon fodder. He realizes that the ideology he has been stuffing into their brains has culminated in them being used as sacrificial lambs. The Captain is obstinate, but the seed is planted, and again this comes back into play later.

After a single day in training for the kids, the military installation is notified of a breach. The Americans are encroaching and will arrive in the town. Every able person, whether seasoned or brand new, are told to take up arms and not let his country down. He addresses all of the military, and reminds the youngsters that even though they are not experienced, that the German way is to always go forward, not backward, and not to forget that they are being charged to protect the fatherland. We see uncomfortable looks, both from the crowd and from other officers. They all know what this means. We as the audience know that the officers are pressing the buttons of the programming that the children had undergone at school. This is phrasing they can relate to. They want to be men and do their duty. Wicki is attacking the fact that children were led to believe such things.

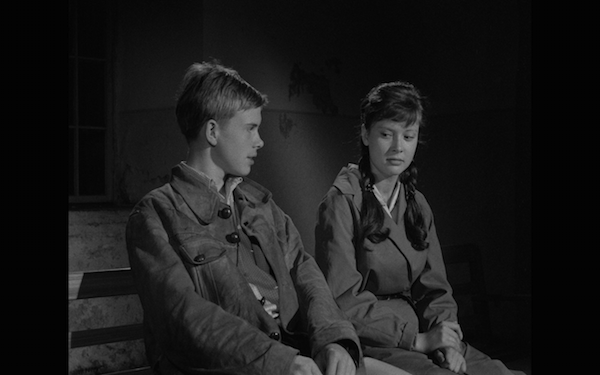

Through a mishap of communication, the boys end up on the bridge without supervision. They are surprised that they are ordered to defend the same bridge that they walk over everyday, with their homes within walking distance. They eat food together, laugh together, mostly oblivious to the horrors of war that await them. They even ignore a warning from a citizen passerby. It isn’t until they see a truck of troops coming back, specifically the gravely wounded troops, that it finally dawns on them what their near future could hold.

When an aerial attacker shows up nearby and one kid hits the deck, the children lambast him for his cowardice. Soon after, a viable air threat heads straight for them. The entire company hits the deck except for that one brave soldier, proving that he is just as brave as all of them. This misguided thinking costs him his life.

The onslaught continues as tanks appear within the town. The kids, without any orders to respond to, take it upon themselves to ferociously defend the bridge. They even succeed in taking down a tank, but the Americans realize that they are fighting children. One of the Americans even calls at the kids in English to stop. “Kid, what are you doing in this friggin’ war?” he yells. Good question. Another American says, “we don’t fight kids. Stop! Go home!”

The children do not listen to any of these warnings, just like they hadn’t heard any of the other ones. Wicki is saying that it was the system that placed these ideas in their head, and shielded them from the true horrors of war. When they finally see the horror, it is too late. They shriek and cry, but their fates are sealed. It is a tragedy, and their blood is on the German machine’s hands. Coming in 1959, this film at least to the younger generation is a way of processing and coming to terms with how misguided the older generation was. The Bridge, however tragic, is a catharsis.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Gregor Dorfmeister: Author of the novel in 1958 in 2015.

The book was a fictionalized account of his experiences as a teenager at the end of the war. He was 29 when it was published. He was 86 during the interview.

He lived the situation. They were high school classmates that were ordered to defend a bridge. He remembers getting his draft notice at 16 and being excited. He was in the Hitler Youth because he enjoyed the time in sports, but of course they were being groomed to become soldiers.

He remembers hearing the sound of the American soldiers coming into town, which he says was captured perfectly in the film. In reality they threw eight grenades at the tank, and two of them hit. He saw an American GI leaving his tank with his back completely ablaze. The experience horrified him and made him a pacifist for the rest of his life.

The premise of the book was to show that they were caught up in the Third Reich, like “cogs in the wheel.”

Bernhard Wicki: 1989 excerpt from German TV.

Wicki graduated in 1938 and was arrested by the Nazis before the Kristallnacht, and was then sent to a concentration camp for 10 months. It is a difficult memory for him to reflect upon, but because he was 18 probably made it easier. He ended up making political films not just because of these experiences, but mostly because this was something he knew.

The interviewer called The Bridge “drastic realism,” which Wicki disagreed with. He likened it to neorealism, and noted Rossellini, De Sica, Visconti, who were his models. The success of the film became a burden on him professionally because it set expectations high. People wanted him to make a film of its caliber.

Volker Schlöndorff: 2015 Criterion Interview

The Bridge was his cinematic role model. There had been a number of war films in the 1950s, most of which were about “the good German” soldiers. The younger generation did not want to see the movies. Wicki’s film resembled some of those films, but the spirit was different. The Bridge is about death being an abstract notion and then the realization of it as a reality.

To the young filmmakers in the 1960s, Wicki was a something of a Godfather. At the time, they had reservations about the older generation. Most of them stayed away from the old actors, even Wicki (except for Wenders in Paris, TX. They all liked him and visited him, but few of them worked with him.

Against the Grain: The Film Legend of Bernhard Wicki: Excerpt from 2007 documentary with behind-the-scenes footage.

The Germans did not have suitable tanks,. And the Americans would not give them until they read the script. Initially Wicki did not want to work on the movie because the novel was about German bravery. He had to change certain elements of the tone.

The film because famous worldwide and was notable as a respectful anti-war film that showed a sea change. It had political implications.

Criterion Rating: 8.0

Top 20 of 2012

You may be wondering why I am posting this today when I just posted 2013 yesterday. That’s easy. I forgot to post 2012 back when I put the list together a number of months ago. I just realized it after updating the Lists section to add 2013. Oops.

As I mentioned yesterday, it is difficult to rank recent film because age is the ultimate arbiter. As it turns out, when I dusted off this list, I found that some films had already fallen out of favor. The changes are only minor, but the fact that I made changes this soon means that in a year, two, three, and definitely ten, the changes will be a lot more drastic. Maybe I’ll plan to revisit these lists every so often as an exercise in how tastes change.

For now, this is the list. It is still English-language heavy, but it has six international releases versus four from 2013. There are three documentaries, and the last entry on the list is actually from the Persona Criterion edition. Liv & Ingmar was not on the original list. The only other Criterion title is Frances Ha, which I have not yet seen on Criterion, but I have a suspicion that it won’t hold up as well on a second viewing.

1. Zero Dark Thirty

2. The Act of Killing

3. The Master

4. Mud

5. Laurence Anyways

6. Life of Pi

7. Holy Motors

8. Looper

9. Marley

10. Frances Ha

11. Broken Circle Breakdown

12. A Royal Affair

13. The Hunt

14. Cloud Atlas

15. Cabin in the Woods

16. Beasts of the Southern Wild

17. What Maisie Knew

18. Skyfall

19. The Attack

20. Liv & Ingmar

Top 20 of 2013

I’m always reluctant to post lists for recent years. Even though I consider myself a general film fan, I am mostly a classic film fan. Good films age better with time. Flawed films do not. My top 20 list for 2005, for example, is a lot different today than it would have been in 2005. This list will probably be a lot different in 10 years, partly because films age differently, but also I’ll have opportunities to see more gems that fell under the radar, many of which will probably be international films.

As it turns out, this is an English heavy list. My top four were all late Fall, “awards season” releases, and top pick won Best Picture at the Oscars. Now that’s a rarity. It’s also the subject of one of the first posts I wrote on this site — a historical analysis, and quite different from the posts I write now.

There are some omissions. Gravity missed my list, but that’s not to say that I didn’t appreciate and respect the film. It was one of the most technically impressive films in recent memory. I actually liked it more in the theater, and it dropped a notch when I watched it in 3D at home. It felt more like a roller coaster ride than a film.

Inside Llewyn Davis is one that has grown on me over the short time since I’ve seen it, and now I think it as one of the better American character studies, and an underrated Coen Brothers film (which feels weird saying). It is rumored to come out on Criterion someday, and I would really enjoy revisiting Llewyn’s world, however bleak it might be.

1. 12 Years a Slave

2. Inside Llewyn Davis

3. Captain Phillips

4. Wolf of Wall Street

5. Enemy

6. We Are the Best

7. The Spectacular Now

8. The Great Beauty

9. Computer Chess

10. The Wind Rises

11. Under the Skin

12. The Armstrong Lie

13. Jodorowsky’s Dune

14. The Immigrant

15. Blue is the Warmest Color

16. Ida

17. 20 Feet From Stardom

18. In a World

19. Before Midnight

20. The World’s End

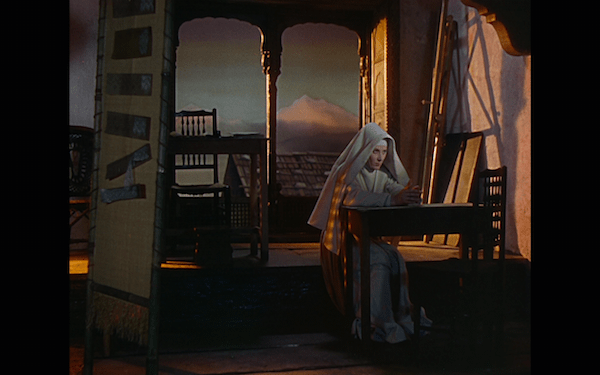

Black Narcissus, 1947, Powell & Pressburger

This post is part of the 1947 Blogathon hosted by Shadows & Satin and Speakeasy.

I was at dinner with friends a few months ago, one of whom happens to be a huge Powell & Pressburger fan. We were sharing thoughts on their 1940s output, pretty much raving about film after film. When we got to Black Narcissus, without thinking I said, “I just love the locations they used.” The thing is, they didn’t use locations, and I knew that. Everything was a set, but for a split second as I reached down into my memory bank about this film, my first image was the castle near a cliff at high Himalayan elevation. My thought was not of the matte paintings or miniatures, but the fantasy that they created.

The remainder of the film notwithstanding, the creation of this world is a marvel. Sure the matte paintings of the mountains in the opening sequence scream matte paintings. As they establish the “location” with a series of shots, it is easy to tell if you look carefully that they are using miniatures, especially viewing with modern eyes. As the film progresses, however, it begins to feel like real India. We get lost in that world, thanks to Michael Powell’s idea to shoot everything in the studio, and Jack Cardiff and Alfred Junge’s monumental work to make Pinewood Studios not only look like the Himalayas, but for it to look magnificent.

I could go on gushing about the sets, the use of color, but the pictures do most of the justice. Under this gorgeous backdrop is a story of isolation, perseverance, self-repression, and at the core, eroticism. Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) is charged with an expedition to open a convent in Mopu, to educate and assist the locals, in challenging, arduous terrain that slowly wears her and her fellow sisters down.

Deborah Kerr has proven repeatedly that she is a tremendous actress. One of her most impressive turns was the triple-role she played in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. In Black Narcissus, she has to play an entirely different type of character, but she pulls it off magnificently. As you see from the above tweet, she was poised and composed most of the time. Her performance shined in the nuances – the brief moments that she let her guard down. When a masculine figure like Mr. Dean makes a suggestive comment, we can see that it registers and she hesitates, but she is aware of her position of leadership and hiding her true feelings.

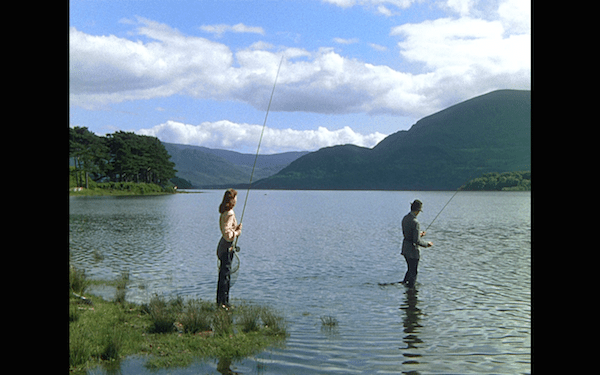

We see in flashbacks that Sister Clodagh was not always a chaste, innocent servant to religion. At one point, she had a love in her life and a carefree lifestyle doing something just for fun — fishing. During her moments of weakness in Mopu, she longs to return to those halcyon and unobtainable days in her life, lamenting the life of solitude that she has chosen for herself.

All of the Sisters face their own challenges, and one of the obstacles that Clodagh faces is dealing with attrition. However, her most notable adversary is Sister Ruth, played to perfection by Kathleen Byron. Ruth is stubborn at times, and highly sensitive at others. While Clodagh is quietly and stoically beginning to crack, Ruth is not just unraveling, but spiraling out of control. She falls the furthest from grace, and the rivalry between the two women makes the final act memorable, but this time I will not spoil the ending. Plus, I’m getting ahead of myself.

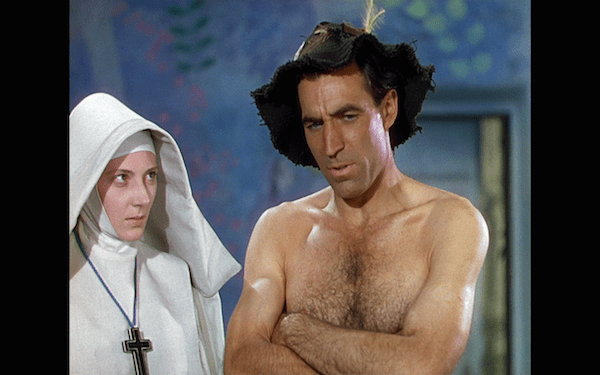

When one thinks of a nun movie, erotic is not a word that would come to mind, yet Black Narcissus is stacked with eroticism, which is the undercurrent for how the plot plays out. The world of Mopu is an erotic world. The nuns decide to take in one of the young local Generals (Sabu) for political reasons, and he dresses ornately and wears the titular cologne that he calls “Black Narcissus.” The naming of the scent speaks to the futility of the nun’s cause, and how the idea of civilizing the local “Black” population is a narcissistic exercise under the questionable philosophy of “White Man’s Burden.” Yet, the scent is intoxicating, and the Sisters find themselves attracted to the General’s charms.

The most sexualized character is a male, Mister Dean, who serves to mentor the women. He is their western conduit that informs them of the eastern ways, but he is also the most significant threat to their vows. He is a temptation for the women, and just like the constant wind, he slowly weathers down Sisters Clodagh, Ruth, and others. He is introduced wearing shorts and revealing clothing, and he is portrayed by David Farrar as a masculine outdoorsman. In one scene he arrives at their sanctuary not even wearing a shirt. What is the practical benefit of shedding clothing at elevation with the wind constantly blowing?

Ruth admires Dean from a distance, but he interacts with Sister Clodagh regularly. She manages to keep her true feelings close to the chest, but there are many suggestive lines of dialogue, quick glances, tiny fissures in her icy exterior that show she is aware of the temptation. In one early scene she notes that they are to talk business, and Dean responds that, “I don’t suppose you’d want to talk about anything else.” That other, unspeakable subject is of romance, or more specifically eroticism, voicing the prospective attraction they hold for each other. They play games, at times civil, at others hostile. In one scene, Dean sings Christmas Carols while drunk. Clodagh pushes him away, which is in part distancing herself from the threat by telling him “you’re objectionable when you’re sober and abominable when you’re drunk!”

The other sexualized character is Kanchi, played by a young Jean Simmons as her career was beginning. Kanchi is taken in by the convent as a pity project, but she is the antithesis of everything the Sisters represent. She is beautiful, wearing seductive jewelry and clothing, and even does a provocative dance. While the nuns have to keep their eyes aloof, Kanchi overtly presents herself as a sexual object. When the General reveals his cologne, the Sisters have no choice but to ignore the magnetism of the scent, but Kanchi holds nothing back. She savors in the charms of the General, and even though she is low by birth, she does everything in her power to win over the young, vulnerable man.

This sexual tension progresses throughout the first two acts, and it is the third act in which the Sisters, specifically Clodagh and Ruth, are faced with it directly. It is not a sword, gun or any other weapon of war that sets the film toward its thrilling conclusion, but a mere tube of lipstick.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements

Commentary 1988 with Michael Powell and Martin Scorsese.

This is a commentary I had already heard, so I did not re-listen/re-watch. I remember it being an excellent commentary, as was their commentary on The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Much of what they discuss is repetitive with the information found on the other features of this disc.

Bernard Tavernier: 2006 Introduction.

This was the first time they had adapted an existing work and not wrote their own screenplay. As Tavernier puts it, they adapted “between the lines” of Rumer Godden’s novel. We learned from The River that she was not satisfied with their adaptation and was careful to make sure Renoir would handle the material to her liking.

The Audacious Adventurer: 2006 Bertrand Tavernier interview.

Marie Maurice brought the book to Powell and Pressburger, and said they should adapt the film and she should play Sister Ruth. At first Powell did not pursue the film because he did not want to adapt other material. After the war, Powell had been tired of war films. Pressburger then remembered the book and talked him into the project, but Maurice did not get the part.

Casting was the next task. Kerr was the first to be suggested, but Powell discounted her because she was too young. Kerr heard this and when they had lunch, she convinced Powell that she was just right for the part. She said that age wouldn’t matter. Jean Simmons caused controversy because Olivier had contracted her to play Ophelia, and he took exception to her playing an erotic Indian. There was some friction between Olivier and Powell as they discussed/debated Simmons.

Jack Cardiff had not been a Director of Photography on a film, but had worked for Technicolor. Powell took a risk in hiring him for his first film, and the rest is history. He won the Oscar for Cinematography and would continue to collaborate with Powell, and had a highly successful career.

Powell decided on shooting everything at Pinewood because they would never be able to match the exteriors in India with shots inside a London studio. Cardiff and Junge had harsh reactions. They creatively looked for solutions, and decided to use miniatures and glass. Lucas and Spielberg have said that the special effects had never been matched.

Profile of Black Narcissus: 2000 making-of documentary.

They have interviews with Jack Cardiff, Kathleen Byron, and many others.

After a series of major successes and the previous year’s A Matter of Life and Death, Powell and Pressburger were at the top of their game. The question was what would they come up with next, which of course resulted in this ambitious project about ex-patriot nuns in the Himalayas.

The entire film had been shot in the British Isles. Not one frame was shot elsewhere. Pinewood became this exotic far away land. Cardiff said that after the film, they had letters saying that people had recognized places they had visited. This he felt reinforced that they had succeeded with the charade.

The tension between Sister Ruth and Mr. Dean was heightened by their off-set relationship. Byron says he had crushes on many women. As she puts it, “we were very close at one time, but it was not for very long.”

Painting with Light: 2000 documentary about Jack Cardiff’s work.

They have a number of interviews, including Martin Scorsese, Hugh Laurie, Cardiff and others.

Cardiff shows the mechanisms in the camera that shows how the color was captured. Scorsese says that films were continually being used for entertainment (as they still are) and Technicolor was used for popular genre films. It added about 25% to the budget

One thing Cardiff did was collected the best technicians around, and had a wonderful art director. It was a tough process and they needed Technicolor consultants on the set at all the time. They had to make sure the colors were right, and even had to dye the shirts to make sure the white did not contrast. The actual colors were bright “Technicolor colors.”

Vermeer was used as a model as to how to portray the light, but as Cardiff puts it, in the Vermeer paintings, the people did not move around. He used the Van Gogh pool hall painting as a model for another scene. Rembrandt was used to inspire other scenes.

Criterion Rating: 9.5/10

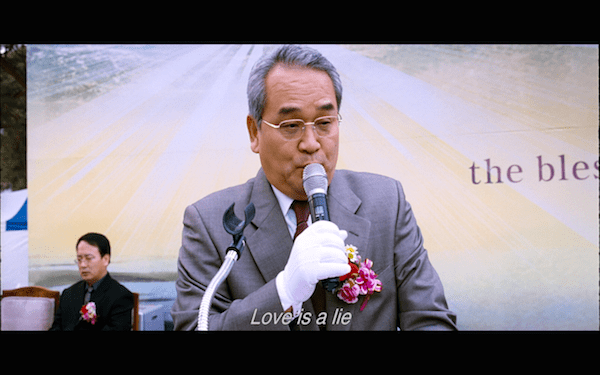

Secret Sunshine, 2007, Chang-dong Lee

Secret Sunshine begins as an ordinary character piece, with a widowed mother planting roots in her husband’s hometown as a way to begin fresh. We can tell early on that the bonds between the mother and her son are tight. In the opening scene, when they have a car breakdown, she tells her son that “we’re stuck together.” Most of the early scenes are spent developing the mother character, Shin-ae, and how she is out of her element in the small city of Miryang. She does not fit in with the crowd, and finds that when she tells one person her backstory, the entire town knows her story. Her only friend is her son, and they could not be closer.

Towards the end of the third act, a crime takes place. It is a devastating crime, one that impacts all of the characters and forces the story to take a left turn. When the crime is revealed, it appears momentarily that the film is going to transform from a drama to a thriller or crime procedural. While some procedurals can be well done and have some artistry (Vengeance is Mine for example), I have to applaud the filmmakers for not writing the easier story. It resists falling into the formulaic trappings of the procedural drama. While it does give resolution to the crime, it does not dwell on who did what, how the investigation or trial were carried out, or anything else pertaining to the process. The closest we get is the main character visiting a crime scene. Secret Sunshine deserves credit for not succumbing to the lure of the thriller, and instead focusing on the characters.

Be warned that after this image, I’ll be delving into spoiler territory. Please do not read further unless you have seen the movie or could care less if I give it away.

The pivotal scene is the kidnapping of Shin-ae’s beloved son, Jun, and his subsequent death. As noted above, we do not dwell on finding the killer, but they do find him and put him away. If you pay attention, you can see who it is in the narrative, and there is an emotional payoff in one of the final scenes for those who paid attention to his daughter. All of the details about the crime are for the most part unnecessary aside from that it happened and devastated the mother.

Religion is a major theme, and it intermingles with the title, which also happens to be the Chinese translation of the city’s name. Miring means “secret sunshine.” Religion is introduced early in the film before the kidnapping. When Shin-ae picks up a prescription, the pharmacist gives her a religious pamphlet and encouraged to join the local service. This is where the gossip comes into play, as the pharmacist already knows that she is widowed and a single mother, and makes assumptions about her character from there. Shin-ae actually denies the assumptions and is insulted by them, but through the performance, we learn that the pharmacist was correct. Shin-ae is a traumatically wounded woman.

It is not just religion that is a core theme, but belief in general. The pharmacist tries to convince her to “see the light” on more than one occasion. At first, Shin-ae is a stringent atheist. She does not believe what she cannot see. During one of their discussions, the pharmacist notes that God is within the sun beam that is shining through the store window. Shin-ae walks through it defiantly, noting that there is nothing there.

An aging, unmarried male named Jong Chan consoles Shin-ae after the tragedy. He meets her in one of the film’s early scenes when her car breaks down, and develops a longing for her. For much of the film, it appears his intentions may be admirable and platonic. When people ask of his sexual intent, he dismisses saying that “It’s nothing like that.” In truth he is simply bashful, yet he watches over Shin-ae as she grieves. You could call this being in the “friendzone,” but there is a chemistry between them – whether it is as friends or partners – she usually welcomes his presence, even if at times she tries to rid herself of him.

Shin-ae changes her mind about religion, or at least decides it is worth a try. Anything is worth trying if it might relieve her suffering. She goes to church and Jong Chan tags along with her. It is over a few scenes that she completes her conversion, but we are meant to infer that this takes place over a long period of time. The film moves through time quickly. Shin-ae finds exactly what she is looking for through religion, and finds what at first appears to be true happiness. She makes friends with the local community, even goes out to Karaoke bars with the girls, and has finally settled into Miryang living. Her transformation is remarkable, and the girls applaud her for getting her life in order after losing her husband and son.

At one point, she decides that she is strong enough to forgive Jun’s killer. She decides to visit him in prison, bring him flowers, and through the power of the Lord, offer forgiveness. Is she doing this for herself or for him? This isn’t clear, but we get an idea after they meet. Rather than living a miserable life in prison, she finds in her son’s killer a well-adjusted man, looking healthy and serene. When she reveals why she is there, he is pleased. He too has found solace in God. He has achieved forgiveness. Shin-ae is shaken. How can God forgive him when it was her that was bereaved? How can God be allowed to forgive someone without the injured party also forgiving? As quickly as Shin-ae became Christian, she just as quickly loses her faith.

If Shin-ae was apathetic towards religion before she lost Jun, she is aggressive toward it after being robbed of her forgiveness. At first she lashes out just because of the unresolved pain she is feeling, part of which she feels religion is to blame. In a particularly intense scene, she begins crying during prayer in a church service. That prayer turns to a guttural wail. She screams out as if she is physically hurting. Even though Jong Chan is still behind her, trying to console her, the fire cannot be put out. She turns further away from the church, finds an outdoor retreat and sabotages the audio equipment to a song with lyrics about how everything is a lie. This plays while the pastor is preaching about God’s plan, but his sermon is drowned out by Shin-ae’s song.

There are some logical problems with certain plot elements. Even though we are led to think that a lot of time has passed, it’s a stretch to believe that Shin-ae could be depressed, then so happy that she cannot contain her wide smile, to depressed again and wanting to leave her life behind. It’s also unlikely that someone would be brave enough to forgive someone who had committed such a heinous act as kidnapping and killing a son. I had trouble believing certain things, yet I was able to mostly get past them. That was thanks to the remarkable performance.

If the lead performance were poor, this film would not have made it out of South Korea, much less made it into the Criterion Collection. The performance is devastating. Do-yeon Jeon is believable in the highs and lows of her character. At times her emotions are so strong that it hardly seems like acting, and this is the case whether the character is feeling grief or elation, although the performance really stands out when she is hurting. The emotional low that Shin-ae falls cannot have been an easy place for the actress to reach, but for the most part, she knocks it out of the park. This is one of those films where the lead performance is so strong that it triumphs over what would otherwise be mediocre material.

Finally, this is not a pleasant film. It reminded me of a slightly less harsh version of Lars Von Trier’s Breaking the Waves. Like Bess, Shin-ae has her demons and deep down, has a virtuous side. Both are martyrs. The only difference is Bess’ sacrifice gets her closer to God, whereas Shin-ae could not be further when she decides to leave her life.

Film Rating: 7.5

Supplements

Lee Chang-dong: 2011 interview.

“What is the meaning of ordinary lives?”

This is not a story about an event, but about a place. He chose Miryang because it is an average small town. It was near his home town, but he was always fascinated by the name even at a young age. It is a poetic name. He used many locals for the cast, either theater actors or amateurs.

He did not intend for this to be a religious film, but it is a film about God. Jong Chan could be interpreted as a god-like character or perhaps sent from God to watch over her. He literally does watch over her in many scenes. He is an “earthy” person that could be good for Shin-ae, but she rejects him. The actor did a good job with the local dialect that foreigners will probably miss out on, but that contributes to his “earthiness” (I think he means “down to earth” with this phrase).

He did not direct the Do-yeon Jeon or her emotions much. He wanted her to draw on her experiences, which makes her performance that much more impressive given that it wasn’t directed. She had a tough time on the set because there were painful scenes day after day, so the actress had to suffer. She was at odds with the director, but they made up after the shoot was complete.

On the Set of “Secret Sunshine”:

This is a short, 6-minute film, which basically shows little outtakes from the set. For example it starts with the two leads laughing about wondering how the film will look when it comes out. They are both curious because the style it seems new. They show a montage of misery from Do-yeon Jeon.

“Love makes you a fool” becomes a song because they talk about what a hopeless character Jong Chan he is. She calls him a loveable character. He thinks he is a fool.

Criterion Rating: 7/10

The Great Beauty, 2013, Paolo Sorrentino

Believe it or not, this was my third time giving The Great Beauty a chance. The first two times I hated it. In fairness, both of my previous two attempts were not during the ideal circumstances. The first time was on Video on Demand before the home release. I didn’t realize the movie was as long as it was, so I had to cram it in during a busy time before the 24-hour rental period expired. It seemed beautifully shot, but overlong and plodding. The second time was when it was on Netflix instant, before the Criterion release and before I knew I’d be undertaking this ambitious project. That time my take was similar, but I watched it when I was tired and felt it was an inferior La Dolce Vita knockoff. My love for Fellini fueled my hate for Sorrentino.

I bought the Criterion because I buy all of the Criterion Blu-Rays, but it was one I planned to save for a rainy day. Maybe I would watch it last. I decided to try again after talking with Mikhail from the Wrong Reel podcast. I respect his opinions and often agree with him (although not always). He said he considered it to be one of his top 20 films of all time. Really? That was a surprising statement. He also would have La Dolce Vita in the same top 20. That was even more surprising, because I know some other Fellini fans who also despise The Great Beauty. Since I had revisited La Dolce Vita since my last attempt at this film, I figured it would at least be an interesting experiment in contrast, but I did not expect my mind to be changed.

My mind was changed.

The beginning of the film is absolutely exhilarating. I thought that on all three viewings, but it especially took hold of me this time. The film begins in daylight and the camera cuts quickly between gorgeous Roman buildings and vistas, intermingled with shots of random people. We see a Japanese tour group, and one of them dies, which introduces two themes that will come back later – tourism and death, and this moment will be subtly recalled at the end of the film. The camera is rarely static, and instead moves quickly, reminding me of Wenders’ Wings of Desire that gives the sequence a constantly flowing feeling.

Daylight abruptly ends and night begins as we are transported to a vibrant party, introducing a contrast that will continue throughout the film – the splendor of Rome during the day versus the wildness and debauchery at night. The camera moves just like it did in the daytime, with the same type of quick cuts. We see random images of participants, a motley crue of characters, some of whom will return later and some we will leave with the party. The party is a way to memorably introduce the main character.

Hello, Jep Gambardella! When we are introduced to Jep (Toni Servillo), he is clearly in his element. He dances to the hypnotic music, has a beaming smile, and soon will randomly French kiss one of the beautiful women. This is his 65th birthday party, and although he has the gray hair, he acts like someone half his age. He is a partier, living for the nightlife without a care in the world. He is affable, casual, fun loving, and we immediately understand why such a huge crowd flocks to his party. He’s the kind of guy people want to know, and even at 65, the kind of guy that people want to be.

I cannot write this without highlighting the similarities between Jep and Marcello from La Dolce Vita. They are both journalists. Marcello wrote for gossip magazines, whereas Jep interviews various figures from performance artists to religious figures. Jep is the more prestigious writer, both presently and in his past, having written a novel (or novella, as it is sometimes referred) forty years ago that sounds to have reached a level of popularity and literary credibility that Marcello was not within sniffing distance. They both are having an aging crisis, although Jep’s has more to do with being close to mortality, whereas Marcello is having a mid-life crisis. They both live for the night. In both films they go to parties and gallivant around Rome at night.

The similarities end there. Marcello is a bitter individual, whereas Jep upbeat, yet cynical about life and society and can be caustic, particularly when he verbally takes down a fellow, hubristic writer. They are both charismatic and well liked, but Marcello is downbeat and soft spoken. Jep has his somber moments, but even when he is questioning his place in life, he still carries himself with composure and is not nearly as aloof as Marcello. It is also worth noting that in both films, the writers encounter a young girl. The one that Marcello meets is fond of him, and does not see his bitterness, whereas we barely even see the one that Jep encounters. She is underground and Jep speaks to her through a sewer grate. She tells Jep that he is nobody.

There are a few other filmic elements and plot points that evoke memories of Fellini, and I was surprised to find in the supplements that the filmmakers were not consciously updating Fellini. I’m not saying they are being disingenuous. Perhaps these similarities were accidental or unconscious, or maybe they are just being coy about their inspiration. Either way, I think it is fair to make comparisons.

Despite these few similarities, many of which are either plot and character broad strokes, and others that are minor details, The Great Beauty deserves to be viewed on its own artistic merit. It makes many prescient statements and observations about modern life and society.

One reoccurring plot point is the art world. Along the way, we meet a few modern performance artists. One of them is a child who hurls paint cans at a canvas while having an emotional episode. One spectator complains at the exploitation, and is told that she makes millions, implying that commerce is the inspiration rather than passion. Another performance artist begins with knife throwing around a woman. At first the worry is for the woman’s well being, and then when she walks away, we see that the knives left an artistic imprint on the wall. This combination of a carnival act and the art world is important, and would be recalled later.

There is one scene where a man discusses with Jep how he will hide a giraffe. This act is not magic or art, but unequivocally a carnival act. He reveals that it is just a trick. Earlier in the film, a performance artist hurls herself at a stone column and smacks into it head first. This is just part of her performance, but is the most memorable as it appears that she has physically harmed herself, drew blood even, and all for art. It is later revealed that she had a buffer that prevented her from harm, so this was just also trick.

Jep sees these artistic demonstrations during his professional or social sphere. When the sun comes out, another form of art is revealed – the architectural beauty of Rome. Some of the film’s “great beauty” is revealed either during sunset when Jep is beginning his nightly adventure, or when the sun has come up after his night has ended. What he sees on his solo journeys is real beauty, real art, and not artifice.

A moment that is striking both for Jep and the viewer is when he encounters another piece of modern art, but he stumbles onto it by accident during one of his daylight strolls. This piece of art is simple, just a number of small snapshots of the same person on different days. It does not sound impressive by description, but the large number of these pictures as a whole reaches a magnitude that makes it a larger, and more distinct artistic statement. This is life and it is beautiful. You could say that the art itself is a trick because it is comprised of numerous little photos, easy to produce individually, but the end result is something special. The difference is that it has no commercial motive and someone like Jep can wander by it without paying anything.

The film touches on a number of other subjects and themes that I could write thousands more words about, such as the nature of death, love, tourism, classism, resistance to aging, religion, and plenty more. On this third viewing, I saw a dense and complicated film that is about various forms of beauty. “The Great Beauty,” however, is just a trick.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Paolo Sorrentino: 2013 discussion with film scholar Antonio Monda.

Monda talks about meeting Sorrentino when accepted One Man Up for the Tribeca film fest’s first year. Scorsese asks Monda to call him because he was Italian, and it happened to be on April Fools Day so Sorrentino thought it was a joke.

Jep was intentionally supposed to be a likeable and casual figure, who had a cynical outlook on life and the world. They had seen people like that in Italy (particularly Naples) and it was not a tough character to envision. The “medium long” hair was a negotiation. Sorrentino wanted it longer.

They talk about the parallels with La Dolce Vita, and Monda wonders whether the broad stroke similarities were conscious. Sorrentino says they were not conscious. He says the only one that was intentional was filming the Via Veneto today. He says that the other references are unintentional, but perhaps subconscious because of his affection for Fellini.

The film is 137 minutes, which is long, but the first cut was longer. He misses those cut scenes and liked the first cut of the film, which was 190 minutes. He was not made to cut the film, but he did it himself. He thought that a long film would be exhausting, and it would perpetuate the theme (my words) that life is exhausting.

Toni Servillo: 2013 Criterion Collection interview.

This was his fourth film with Sorrentino, and he acknowledges that he owes a debt to the man for making his career. They share many ideas and observations, which made their way into the lead character. Paolo even designed the wardrobe, which was based on a Neapolitan tailor. Paolo wanted his Neapolitan flair to be very evident and clear, and not something he tried to conceal.

One thing I loved about this interview was not the words spoken, but the bookshelf behind him. There were books on Selznick & Hitchcock, Zanuck, and African Film Music. Servillo is not only a participant in film, but also a connoisseur and admirer.

Umberto Contarello: 2013 Criterion Collection interview.

Contarello is the screenwriter that worked with Paolo, and like Monda, met him at a festival. Some of his comments are redundant from the Sorrentino interview because he talks about them working together on a film that did not end up getting made. They developed a rapport during this collaboration.

When he heard about the scope of the project, which was Sorrentino’s accumulated thoughts about Rome, he said thought the project was ambitious, but Contarello also had thoughts on Rome that he could add. So they went to it. They did not intend to write a complex film that was a critique of modern society, so they intentionally added dimensions to Jep from things they liked about writers. “He seems fresh off the boat from Napoli” because of the way he moves around the city, but they portrayed him as if he lived in Rome for years.

They approached Fellini as an archetype on an unconscious level, basically repeating Sorrentino’s remarks. He compares this to The Odyssey, and that basically every film about a journey is inspired by Homer to a certain degree. A film about Rome cannot help but draw from La Dolce Vita

Deleted Scenes:

Maestro Cinema – Jep visits an aging film director in this short scene. The character has made a lot of films that said little of importance, and wants to make a film that says something. The director is the opposite of Jep.

Montage – This is a two-minute collection of deleted scenes. I’m actually glad they did not include the entire long cut, even if the scenes were good (and they do look good), but that would have been too much. Sorrentino was right to cut this film down. That said, one day I would like to see the longer film.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

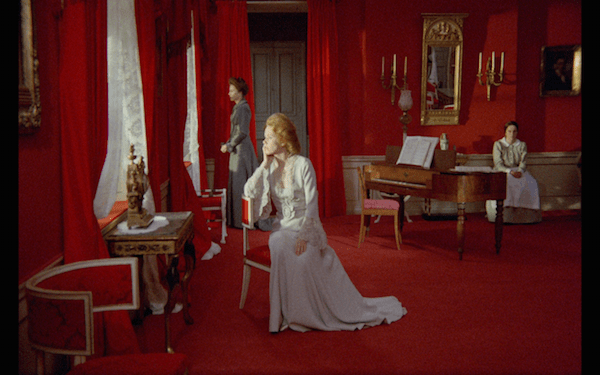

Cries and Whispers, 1972, Ingmar Bergman

By 1972, Bergman was already established as one of the titans of international art cinema. He had won several awards at Cannes and been nominated for two Academy Awards (he would eventually be nominated for 9, including three for this film). Cries and Whispers is not a film that could be made by anyone. It could not have been made by Ingmar in his younger years. It could be seen as a spiritual sequel to Persona, which was really his first foray intro surrealism and immersive, abstract character exploration. Cries and Whispers does not share many thematic or plot elements with this predecessor, but it does utilize the supernatural and it explores these four characters nearly as deeply as the two (or one?) in Persona.

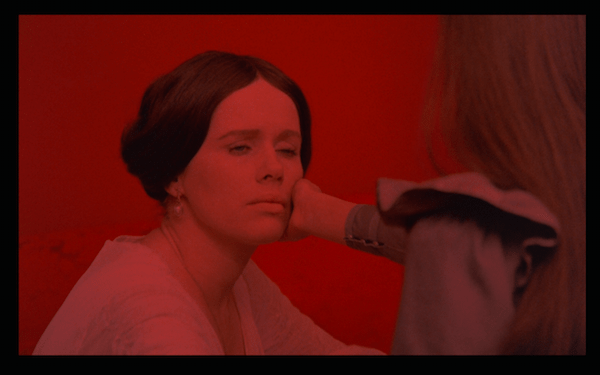

Another similarity between this and Persona is the visual canvas. Persona was in black and white, but I think of it as starkly black and starkly white, almost to the point where it has the same effect as a color film. Cries and Whispers is a color film, but it is nearly a red and white film. The reds are stark and stunning, while the whites are a contrast, just like the whites were in Persona. The colors are visual motifs as well, as red signifies death, mutilation, and white represents the innocence of a lost and nearly forgotten childhood. Sven Nykvist rightfully won an Oscar for his work, and Bergman and crew deserve praise for creating such a visually remarkable red-and-white world.

The color of red is used most effectively for the scene transitions. At the end of a scene, the image dissolves into a red canvas, which gives it a surreal quality. It is a continual reminder of the central theme of death, as Agnes fights her battle with uterine cancer. Sometimes Bergman freezes in the middle of the dissolve, holding on the blood red screen to give us time to ponder and process the meaning of the scene. These transitions and the slight deviations with each one heightens the impact of the color red. I can think of many movies that have used a single color to dictate the theme, some of which are done well (Kieslowski’s Red for example), but none that used it to this extreme, creating what is basically a red and white film.

Please be warned that from here on our I will be delving into spoiler territory.

Harriet Andersson as Agnes gives the most memorable and challenging performance as she tries to cope with the pain and her imminent, unavoidable death. The anguish on her face is heartbreaking and convincing. Much of her performance is given in grunts and grimaces. She is at her most vocal at the very end of the film, but this is after she has passed and the pain has left her. Only the loneliness and the yearning for comfort remains. She seeks solace from her two sisters, yet receives it only from her housemaid Anna (Kari Sylwan) in an unusual yet effective manner.

The sisters, Maria (Liv Ullmann) and Karin (Ingrid Thulin) are complicated characters, at times polar opposite from each other, yet there is some grey (or red?) area in between. To her sisters, Karin is stoic and stubborn, refusing and being repulsed by intimate contact. Maria is affectionate and compassionate, yet she is unscrupulous, making out with the doctor watching over Agnes. In flashback we see Maria and the doctor having an affair, which results in her husband attempting suicide. Karin also flashes back, but her memory is of fidelity and mutilation. She says “nothing but a web of lies” as she abuses herself with broken glass and then exhibits a grisly scene for her stunned husband.

At Agnes’ funeral, the priest says that they had many talks and her faith was stronger than his. Is this why she is able to come back? This is never explained, but the ensuing revisitation with Anna and the sisters has differing results. Maria, who was affectionate to Agnes in life, rejects her in death. Karin also rejects and hates her resurrected sister. Again, the only character that gives her any comfort is Anna, yet the living relatives treat her with scorn and dismiss her as if she was a piece of trash.

The film can be interpreted a number of ways. It speaks to the intimacy (or lack thereof) of family, and how familial love and companionship is fleeting and unobtainable in later life and especially in death. It speaks to the wickedness of the upper class, and how true camaraderie and goodness comes from those that are not clouded by a privileged upbringing. It also says that personal relationships are ultimately rooted in selfishness. With their husbands and other sisters, the sisters care only for what they receive. The same is true about Agnes, who we learn little about, but she is also selfish for intimacy and companionship. The only true altruistic and benevolent character is Anna. She pledges to care for Agnes in life and in death with no financial recompense. At least Maria, who despite her flaws is the most considerate of the other primary characters, and gives Anna a little something to help. Maybe there is hope for humanity yet.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Bergman Introduction: 2003 on the Island of Fårö.

This project came about in winter on the island. It was melanchology time for him because he had just been broken up with someone. He was lonely with only a Dachshund to keep him company. He had an image of a room completely in red. He believes that if the image persists, you should keep writing.

Harriet Andersson – 2012 Stockholm interview with Peter Cowie.

This was just like the interview on the Summer with Monika disc, and was probably recorded in the same session. Harriet was again very animated and descriptive. She is a great interview at an older age.

It had been 10 years since she had worked with Ingmar. At first she rejected the part because it was too difficult. He said, “Don’t give me that load of crap,” and she took it.

The castle set was wonderful. They had offices downstairs. The red rooms were the studio on the main floor. The floor above was for make-up and wardrobe. Ingmar had said the red room resembled the inside of the womb. Andresson: “Well he says things.” “He like to make small stories.” She implies that he is telling a tale.

They kept her awake at night and that made her look tired. The death scenes were an imitation of her father, which she witnessed. He had a terrible death. She has trouble watching the film now because of that memory.

On-set Footage Silent color footage with audio commentary from Peter Cowie.

This is the highlight of the disc. They have quite a bit of silent behind the scenes footage that includes the set-up, press conference, actresses on location in and out of the house, the cast and crew being fed, editing of the film, rehearsals, and so forth. It is a wealth of material and Cowie gives numerous factoids on the film just by talking over the images. This was almost as satisfying as a good audio commentary.

They talk a great deal about the playwright Strindberg. He had spent summers at the manor that they used as a boy and took inspiration of Miss Julie from lady of the manor. Bergman had adapted Strindberg plays for stage, but never for film. One interesting point is that Bergman’s films were not very popular in his home country, but his Strinberg plays were exceptionally popular.

Ingmar Bergman Reflections on Life, Death and Love: 1999 television interview with Erland Josephson.

This is another enjoyable interview. They do not talk about the films so much as they do personal lives, loves, relationships, and various other topics. Bergman is surprisingly candid.

They talk about children. They both have quite a few (Bergman has nine). Bergman talks about apologizing to one of his children for being a terrible father, when the son says that he hasn’t been a father at all. They all get together every year at Fårö Island and the children have maintained good relationships. None of his children were planned. “They were all love children.”

The women lasted about 5 years until he found a new one, and then he found Ingrid, and then she died. When she decided to marry him, “all other traffic ceased.” He was truly in love. He is friendly with all the other girls that he was ever with, and many (including Liv and Harriet) became part of his acting stable. Elrand points out that all the bitterness subsides over time. With Ingrid he had a close relationship, and he has reverted to solitude now that she’s gone.

They talk about death and the inevitability, and how Ingmar doesn’t fear it so much but Elrand does. Of course he talks about Ingrid and how he planned to leave Fårö to her, but her passing happened and it crushed him. You can tell that his life was still devastated by it even all those years later.

On Solace: Video Essay from :kogodana:.

This is an interesting essay, unlike most on Criterion discs. It uses images and text well, especially the red title cards with white text.

The concept of the three movements is abstract to a degree, and it is easier to watch than for me to explain it here. Basically he says that there are three movements. The first two movements are flashbacks, while the third is a distillation.

He points out a few insightful observations, such as that Karin’s mutilation is inverse of Agnes’ uterine cancer. The final scene recalls “bodily solace” that Anna gives Agnes in earlier scene, which is the central theme of the movie and the thesis of his essay.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

My Journey to British Blu-Ray

Even though I love my Criterions, I have looked longingly quite often across the pond. The one limitation with US releases is that Criterion is basically the go-to label for prestigious classic films. Sure, others have their moment in the sun, but it isn’t much of a comparison. What’s more is that Criterion and Janus have the rights to so many movies that may never see a release (hence the Eclipse sets and Hulu channel). British labels for instance (Arrow, Artificial Eye, BFI, Masters of Cinema, among others) have a wide array of arthouse films available.

The label that intrigues me the most is Masters of Cinema, which could be called the UK version of Criterion. They coincidentally started me on this journey. We were tweeting about a title that was available through Masters of Cinema, and I tagged them, thinking nothing of it. I casually mentioned that down the road I might get a region-free player, but I wasn’t in a major hurry. Frankly, the idea of a region-free player doesn’t excite me. Fooling with firmware and getting a mediocre player is not something I want to do. Masters of Cinema surprised me by tweeting just to buy a British Blu-Ray player and an adapter. How simple! Why didn’t I think of that?

This was on May 20th.

There were a few obstacles. It was difficult to find an Amazon player that would ship to the United States. I finally settled on this player. It was reasonably priced, had good reviews, and looked to be eligible for US shipping. I put it on my wish list and planned to come back when I was ready, probably sometime over the summer.

I also asked Brian and Ryan from Criterion Cast’s Off the Shelf podcast for their suggestions about the best Region-B releases to try. I told them my plans about buying a British player rather than going Region free, and Ryan stopped me right there. He said that even if a player says it will ship, it might not ship. He (or people he knew) had tried to order players, and they simply would sit there and never ship. He contacted service and nothing happened, so he eventually canceled the order.

When I heard this, I placed the order immediately. It was May 27th and it had an estimated ship time of a couple weeks. Fine by me. A little bit of time passed. I checked, and no movement. It had not been “dispatched” as they say in the UK, whereas most Amazon UK orders dispatch within a day or two, sometimes on the same day. I checked again later, and still nothing. Maybe Ryan was right?

I contacted Amazon customer service and asked them the status. They were quite helpful and apologetic, but they explained that the shipment delay was because it had to ship from a distribution center in another country. It would ship around mid-July. Huh? When I heard this news, I had practically given up. I doubted I would ever see the player. I went on with my life and forgot about it, but I did not cancel the order just in case.

Within a week or so, I received a surprising email. The player had been dispatched and was on the way. It even had a tracking number. Now I got excited. I watched as the player bounced around the UK until it stopped in Surrey. I checked periodically, and again, no movement. I was beginning to think that my expectations were getting the best of me again, and that it would never leave Surrey.

On June 20th, a Sunday of all days, I noticed a suspicious package on my doorstep. It looked big and bulky. What did I order? It was an Amazon box, but it wasn’t the pristine looking boxes that you get from Amazon US. It looked like it had been around the world. Well, it had. The Blu-Ray player had arrived!

That was a major step, but that was not the final step. You cannot plug and play a British piece of equipment. We have different plugs. I needed an adapter of some sort. It also had to be the right voltage because our plugs and their plugs generate different amounts. As I investigated the player, I found that it required 250V. That could be a problem as most standard adapters only support up to roughly 150V.

I was back on the detective trail. At first I searched Amazon and found a number of low cost adapters, but in the questions section, most of them said they would not play laptops or other electronics. The others simply did not have the wattage levels. I tried Amazon UK thinking that there has to be something available there for British travelers visiting the states or elsewhere. Oh, there were plenty there, but the only problem is I could not find a single one that shipped to the United States. Sigh.

Back to the drawing board, I tried Amazon.com again. I aimed at a little higher price point and found some more viable options. I settled on this one because it was advertised as “100% Compatible with US, UK, EU, & AU plug/socket standards!” It said it handled up to 250V.

Knowing that Amazon has a good return policy, I took the plunge. There was no shipping drama. It arrived within two days. I was wary of burning the house down, so I found the largest surge protector in the house, unplugged everything from it, and gave this little baby a try. A white light came on. Success!

I tried it with the TV. We have two, one of which is a little older. That one did not work. It said that it did not have the proper resolution to support the player. Sigh. It seemed that every time something good happened, something bad would follow.

I tried the other TV and was prepared for disappointment. The light turned on; the TV was thinking. All of a sudden the language options showed up. VICTORY! The first disc I tried looked gorgeous.

So the whole thing set me back about a month and $80, not to mention all the extra discs I’ll be buying in the coming months and years. Was it worth it? Absolutely!

I’ve already bought some British Blu-Rays and more are on the way, so I’ll follow this up later with a post with the beginnings of the collection.