Category Archives: Criterions

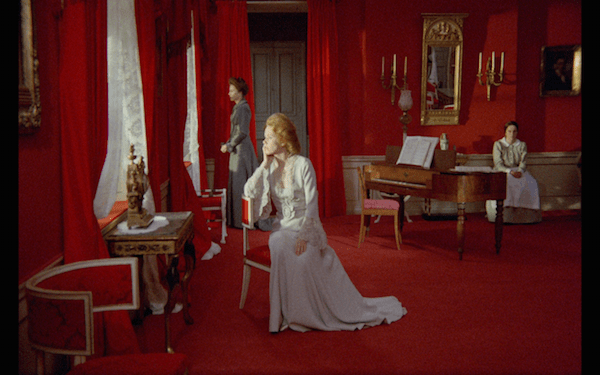

Black Narcissus, 1947, Powell & Pressburger

This post is part of the 1947 Blogathon hosted by Shadows & Satin and Speakeasy.

I was at dinner with friends a few months ago, one of whom happens to be a huge Powell & Pressburger fan. We were sharing thoughts on their 1940s output, pretty much raving about film after film. When we got to Black Narcissus, without thinking I said, “I just love the locations they used.” The thing is, they didn’t use locations, and I knew that. Everything was a set, but for a split second as I reached down into my memory bank about this film, my first image was the castle near a cliff at high Himalayan elevation. My thought was not of the matte paintings or miniatures, but the fantasy that they created.

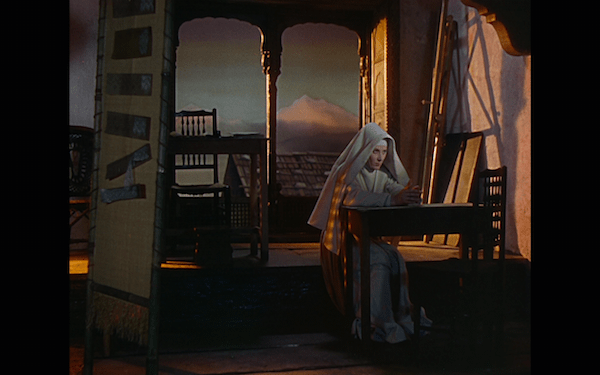

The remainder of the film notwithstanding, the creation of this world is a marvel. Sure the matte paintings of the mountains in the opening sequence scream matte paintings. As they establish the “location” with a series of shots, it is easy to tell if you look carefully that they are using miniatures, especially viewing with modern eyes. As the film progresses, however, it begins to feel like real India. We get lost in that world, thanks to Michael Powell’s idea to shoot everything in the studio, and Jack Cardiff and Alfred Junge’s monumental work to make Pinewood Studios not only look like the Himalayas, but for it to look magnificent.

I could go on gushing about the sets, the use of color, but the pictures do most of the justice. Under this gorgeous backdrop is a story of isolation, perseverance, self-repression, and at the core, eroticism. Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) is charged with an expedition to open a convent in Mopu, to educate and assist the locals, in challenging, arduous terrain that slowly wears her and her fellow sisters down.

Deborah Kerr has proven repeatedly that she is a tremendous actress. One of her most impressive turns was the triple-role she played in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. In Black Narcissus, she has to play an entirely different type of character, but she pulls it off magnificently. As you see from the above tweet, she was poised and composed most of the time. Her performance shined in the nuances – the brief moments that she let her guard down. When a masculine figure like Mr. Dean makes a suggestive comment, we can see that it registers and she hesitates, but she is aware of her position of leadership and hiding her true feelings.

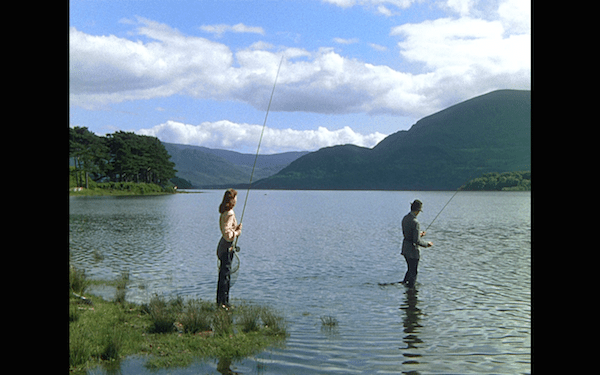

We see in flashbacks that Sister Clodagh was not always a chaste, innocent servant to religion. At one point, she had a love in her life and a carefree lifestyle doing something just for fun — fishing. During her moments of weakness in Mopu, she longs to return to those halcyon and unobtainable days in her life, lamenting the life of solitude that she has chosen for herself.

All of the Sisters face their own challenges, and one of the obstacles that Clodagh faces is dealing with attrition. However, her most notable adversary is Sister Ruth, played to perfection by Kathleen Byron. Ruth is stubborn at times, and highly sensitive at others. While Clodagh is quietly and stoically beginning to crack, Ruth is not just unraveling, but spiraling out of control. She falls the furthest from grace, and the rivalry between the two women makes the final act memorable, but this time I will not spoil the ending. Plus, I’m getting ahead of myself.

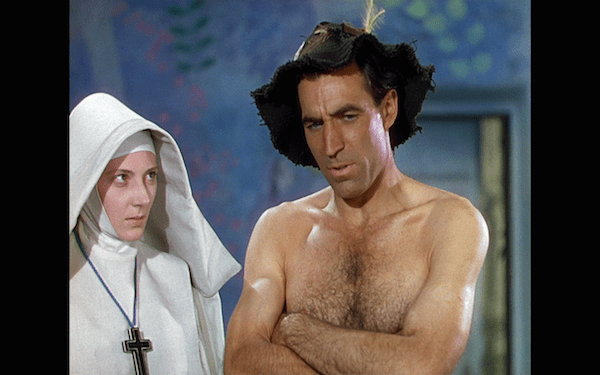

When one thinks of a nun movie, erotic is not a word that would come to mind, yet Black Narcissus is stacked with eroticism, which is the undercurrent for how the plot plays out. The world of Mopu is an erotic world. The nuns decide to take in one of the young local Generals (Sabu) for political reasons, and he dresses ornately and wears the titular cologne that he calls “Black Narcissus.” The naming of the scent speaks to the futility of the nun’s cause, and how the idea of civilizing the local “Black” population is a narcissistic exercise under the questionable philosophy of “White Man’s Burden.” Yet, the scent is intoxicating, and the Sisters find themselves attracted to the General’s charms.

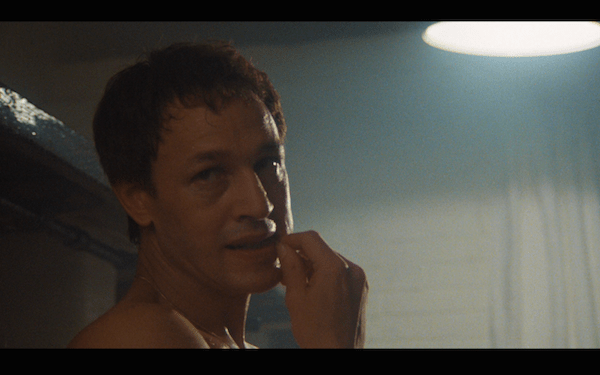

The most sexualized character is a male, Mister Dean, who serves to mentor the women. He is their western conduit that informs them of the eastern ways, but he is also the most significant threat to their vows. He is a temptation for the women, and just like the constant wind, he slowly weathers down Sisters Clodagh, Ruth, and others. He is introduced wearing shorts and revealing clothing, and he is portrayed by David Farrar as a masculine outdoorsman. In one scene he arrives at their sanctuary not even wearing a shirt. What is the practical benefit of shedding clothing at elevation with the wind constantly blowing?

Ruth admires Dean from a distance, but he interacts with Sister Clodagh regularly. She manages to keep her true feelings close to the chest, but there are many suggestive lines of dialogue, quick glances, tiny fissures in her icy exterior that show she is aware of the temptation. In one early scene she notes that they are to talk business, and Dean responds that, “I don’t suppose you’d want to talk about anything else.” That other, unspeakable subject is of romance, or more specifically eroticism, voicing the prospective attraction they hold for each other. They play games, at times civil, at others hostile. In one scene, Dean sings Christmas Carols while drunk. Clodagh pushes him away, which is in part distancing herself from the threat by telling him “you’re objectionable when you’re sober and abominable when you’re drunk!”

The other sexualized character is Kanchi, played by a young Jean Simmons as her career was beginning. Kanchi is taken in by the convent as a pity project, but she is the antithesis of everything the Sisters represent. She is beautiful, wearing seductive jewelry and clothing, and even does a provocative dance. While the nuns have to keep their eyes aloof, Kanchi overtly presents herself as a sexual object. When the General reveals his cologne, the Sisters have no choice but to ignore the magnetism of the scent, but Kanchi holds nothing back. She savors in the charms of the General, and even though she is low by birth, she does everything in her power to win over the young, vulnerable man.

This sexual tension progresses throughout the first two acts, and it is the third act in which the Sisters, specifically Clodagh and Ruth, are faced with it directly. It is not a sword, gun or any other weapon of war that sets the film toward its thrilling conclusion, but a mere tube of lipstick.

Film Rating: 9/10

Supplements

Commentary 1988 with Michael Powell and Martin Scorsese.

This is a commentary I had already heard, so I did not re-listen/re-watch. I remember it being an excellent commentary, as was their commentary on The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Much of what they discuss is repetitive with the information found on the other features of this disc.

Bernard Tavernier: 2006 Introduction.

This was the first time they had adapted an existing work and not wrote their own screenplay. As Tavernier puts it, they adapted “between the lines” of Rumer Godden’s novel. We learned from The River that she was not satisfied with their adaptation and was careful to make sure Renoir would handle the material to her liking.

The Audacious Adventurer: 2006 Bertrand Tavernier interview.

Marie Maurice brought the book to Powell and Pressburger, and said they should adapt the film and she should play Sister Ruth. At first Powell did not pursue the film because he did not want to adapt other material. After the war, Powell had been tired of war films. Pressburger then remembered the book and talked him into the project, but Maurice did not get the part.

Casting was the next task. Kerr was the first to be suggested, but Powell discounted her because she was too young. Kerr heard this and when they had lunch, she convinced Powell that she was just right for the part. She said that age wouldn’t matter. Jean Simmons caused controversy because Olivier had contracted her to play Ophelia, and he took exception to her playing an erotic Indian. There was some friction between Olivier and Powell as they discussed/debated Simmons.

Jack Cardiff had not been a Director of Photography on a film, but had worked for Technicolor. Powell took a risk in hiring him for his first film, and the rest is history. He won the Oscar for Cinematography and would continue to collaborate with Powell, and had a highly successful career.

Powell decided on shooting everything at Pinewood because they would never be able to match the exteriors in India with shots inside a London studio. Cardiff and Junge had harsh reactions. They creatively looked for solutions, and decided to use miniatures and glass. Lucas and Spielberg have said that the special effects had never been matched.

Profile of Black Narcissus: 2000 making-of documentary.

They have interviews with Jack Cardiff, Kathleen Byron, and many others.

After a series of major successes and the previous year’s A Matter of Life and Death, Powell and Pressburger were at the top of their game. The question was what would they come up with next, which of course resulted in this ambitious project about ex-patriot nuns in the Himalayas.

The entire film had been shot in the British Isles. Not one frame was shot elsewhere. Pinewood became this exotic far away land. Cardiff said that after the film, they had letters saying that people had recognized places they had visited. This he felt reinforced that they had succeeded with the charade.

The tension between Sister Ruth and Mr. Dean was heightened by their off-set relationship. Byron says he had crushes on many women. As she puts it, “we were very close at one time, but it was not for very long.”

Painting with Light: 2000 documentary about Jack Cardiff’s work.

They have a number of interviews, including Martin Scorsese, Hugh Laurie, Cardiff and others.

Cardiff shows the mechanisms in the camera that shows how the color was captured. Scorsese says that films were continually being used for entertainment (as they still are) and Technicolor was used for popular genre films. It added about 25% to the budget

One thing Cardiff did was collected the best technicians around, and had a wonderful art director. It was a tough process and they needed Technicolor consultants on the set at all the time. They had to make sure the colors were right, and even had to dye the shirts to make sure the white did not contrast. The actual colors were bright “Technicolor colors.”

Vermeer was used as a model as to how to portray the light, but as Cardiff puts it, in the Vermeer paintings, the people did not move around. He used the Van Gogh pool hall painting as a model for another scene. Rembrandt was used to inspire other scenes.

Criterion Rating: 9.5/10

Secret Sunshine, 2007, Chang-dong Lee

Secret Sunshine begins as an ordinary character piece, with a widowed mother planting roots in her husband’s hometown as a way to begin fresh. We can tell early on that the bonds between the mother and her son are tight. In the opening scene, when they have a car breakdown, she tells her son that “we’re stuck together.” Most of the early scenes are spent developing the mother character, Shin-ae, and how she is out of her element in the small city of Miryang. She does not fit in with the crowd, and finds that when she tells one person her backstory, the entire town knows her story. Her only friend is her son, and they could not be closer.

Towards the end of the third act, a crime takes place. It is a devastating crime, one that impacts all of the characters and forces the story to take a left turn. When the crime is revealed, it appears momentarily that the film is going to transform from a drama to a thriller or crime procedural. While some procedurals can be well done and have some artistry (Vengeance is Mine for example), I have to applaud the filmmakers for not writing the easier story. It resists falling into the formulaic trappings of the procedural drama. While it does give resolution to the crime, it does not dwell on who did what, how the investigation or trial were carried out, or anything else pertaining to the process. The closest we get is the main character visiting a crime scene. Secret Sunshine deserves credit for not succumbing to the lure of the thriller, and instead focusing on the characters.

Be warned that after this image, I’ll be delving into spoiler territory. Please do not read further unless you have seen the movie or could care less if I give it away.

The pivotal scene is the kidnapping of Shin-ae’s beloved son, Jun, and his subsequent death. As noted above, we do not dwell on finding the killer, but they do find him and put him away. If you pay attention, you can see who it is in the narrative, and there is an emotional payoff in one of the final scenes for those who paid attention to his daughter. All of the details about the crime are for the most part unnecessary aside from that it happened and devastated the mother.

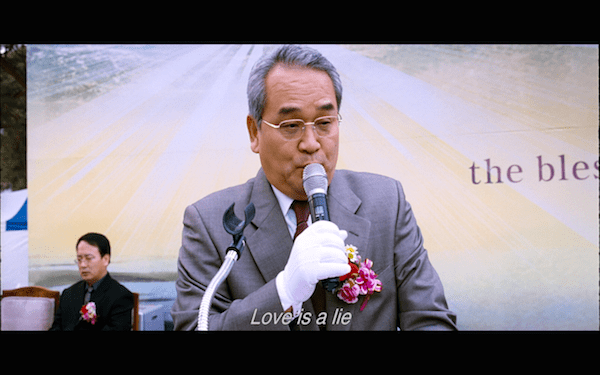

Religion is a major theme, and it intermingles with the title, which also happens to be the Chinese translation of the city’s name. Miring means “secret sunshine.” Religion is introduced early in the film before the kidnapping. When Shin-ae picks up a prescription, the pharmacist gives her a religious pamphlet and encouraged to join the local service. This is where the gossip comes into play, as the pharmacist already knows that she is widowed and a single mother, and makes assumptions about her character from there. Shin-ae actually denies the assumptions and is insulted by them, but through the performance, we learn that the pharmacist was correct. Shin-ae is a traumatically wounded woman.

It is not just religion that is a core theme, but belief in general. The pharmacist tries to convince her to “see the light” on more than one occasion. At first, Shin-ae is a stringent atheist. She does not believe what she cannot see. During one of their discussions, the pharmacist notes that God is within the sun beam that is shining through the store window. Shin-ae walks through it defiantly, noting that there is nothing there.

An aging, unmarried male named Jong Chan consoles Shin-ae after the tragedy. He meets her in one of the film’s early scenes when her car breaks down, and develops a longing for her. For much of the film, it appears his intentions may be admirable and platonic. When people ask of his sexual intent, he dismisses saying that “It’s nothing like that.” In truth he is simply bashful, yet he watches over Shin-ae as she grieves. You could call this being in the “friendzone,” but there is a chemistry between them – whether it is as friends or partners – she usually welcomes his presence, even if at times she tries to rid herself of him.

Shin-ae changes her mind about religion, or at least decides it is worth a try. Anything is worth trying if it might relieve her suffering. She goes to church and Jong Chan tags along with her. It is over a few scenes that she completes her conversion, but we are meant to infer that this takes place over a long period of time. The film moves through time quickly. Shin-ae finds exactly what she is looking for through religion, and finds what at first appears to be true happiness. She makes friends with the local community, even goes out to Karaoke bars with the girls, and has finally settled into Miryang living. Her transformation is remarkable, and the girls applaud her for getting her life in order after losing her husband and son.

At one point, she decides that she is strong enough to forgive Jun’s killer. She decides to visit him in prison, bring him flowers, and through the power of the Lord, offer forgiveness. Is she doing this for herself or for him? This isn’t clear, but we get an idea after they meet. Rather than living a miserable life in prison, she finds in her son’s killer a well-adjusted man, looking healthy and serene. When she reveals why she is there, he is pleased. He too has found solace in God. He has achieved forgiveness. Shin-ae is shaken. How can God forgive him when it was her that was bereaved? How can God be allowed to forgive someone without the injured party also forgiving? As quickly as Shin-ae became Christian, she just as quickly loses her faith.

If Shin-ae was apathetic towards religion before she lost Jun, she is aggressive toward it after being robbed of her forgiveness. At first she lashes out just because of the unresolved pain she is feeling, part of which she feels religion is to blame. In a particularly intense scene, she begins crying during prayer in a church service. That prayer turns to a guttural wail. She screams out as if she is physically hurting. Even though Jong Chan is still behind her, trying to console her, the fire cannot be put out. She turns further away from the church, finds an outdoor retreat and sabotages the audio equipment to a song with lyrics about how everything is a lie. This plays while the pastor is preaching about God’s plan, but his sermon is drowned out by Shin-ae’s song.

There are some logical problems with certain plot elements. Even though we are led to think that a lot of time has passed, it’s a stretch to believe that Shin-ae could be depressed, then so happy that she cannot contain her wide smile, to depressed again and wanting to leave her life behind. It’s also unlikely that someone would be brave enough to forgive someone who had committed such a heinous act as kidnapping and killing a son. I had trouble believing certain things, yet I was able to mostly get past them. That was thanks to the remarkable performance.

If the lead performance were poor, this film would not have made it out of South Korea, much less made it into the Criterion Collection. The performance is devastating. Do-yeon Jeon is believable in the highs and lows of her character. At times her emotions are so strong that it hardly seems like acting, and this is the case whether the character is feeling grief or elation, although the performance really stands out when she is hurting. The emotional low that Shin-ae falls cannot have been an easy place for the actress to reach, but for the most part, she knocks it out of the park. This is one of those films where the lead performance is so strong that it triumphs over what would otherwise be mediocre material.

Finally, this is not a pleasant film. It reminded me of a slightly less harsh version of Lars Von Trier’s Breaking the Waves. Like Bess, Shin-ae has her demons and deep down, has a virtuous side. Both are martyrs. The only difference is Bess’ sacrifice gets her closer to God, whereas Shin-ae could not be further when she decides to leave her life.

Film Rating: 7.5

Supplements

Lee Chang-dong: 2011 interview.

“What is the meaning of ordinary lives?”

This is not a story about an event, but about a place. He chose Miryang because it is an average small town. It was near his home town, but he was always fascinated by the name even at a young age. It is a poetic name. He used many locals for the cast, either theater actors or amateurs.

He did not intend for this to be a religious film, but it is a film about God. Jong Chan could be interpreted as a god-like character or perhaps sent from God to watch over her. He literally does watch over her in many scenes. He is an “earthy” person that could be good for Shin-ae, but she rejects him. The actor did a good job with the local dialect that foreigners will probably miss out on, but that contributes to his “earthiness” (I think he means “down to earth” with this phrase).

He did not direct the Do-yeon Jeon or her emotions much. He wanted her to draw on her experiences, which makes her performance that much more impressive given that it wasn’t directed. She had a tough time on the set because there were painful scenes day after day, so the actress had to suffer. She was at odds with the director, but they made up after the shoot was complete.

On the Set of “Secret Sunshine”:

This is a short, 6-minute film, which basically shows little outtakes from the set. For example it starts with the two leads laughing about wondering how the film will look when it comes out. They are both curious because the style it seems new. They show a montage of misery from Do-yeon Jeon.

“Love makes you a fool” becomes a song because they talk about what a hopeless character Jong Chan he is. She calls him a loveable character. He thinks he is a fool.

Criterion Rating: 7/10

The Merchant of Four Seasons, 1971, Rainer Werner Fassbinder

If you can say one thing about Fassbinder’s films, you can say that he was adept at portraying and processing human feelings. These were usually negative human feelings. For example in The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant, he explored vanity and loneliness, whereas in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, he explored isolation and rejection. There are many other examples, such as Fear of Fear, which is a lesser-known Fassbinder that captures anxiety better than any film I’ve ever seen. With The Merchant of Four Seasons, the emotion that he captures is depression.

I’ll be honest that depression is something I don’t understand. Sure, I’ve had bad days and been down in the dumps. Who hasn’t? I’ve known people that have been depressed, and I’ve had a tough time connecting with them. One friend sent me this cartoon link from Hyperbole and a Half, which helped me understand depression to a certain extent. I can never understand it as well as people like this friend or (likely) Fassbinder experienced it, but a film like The Merchant of Four Seasons gets me closer.

As fair warning, this is a film that requires spoilers to discuss properly. If you haven’t seen the film or are spoiler sensitive, then I would not read this entire post.

The character of Hans is a disappointment to most in his life. When he returns from the military, after finding out that someone else did not make it home, his own mother says, “the best are left behind while people like you come home.” We learn later that his military career ends with a sexual transgression. He then becomes a cart merchant, peddling fruits for a small profit in order to support his wife and daughter. When he isn’t working, he drinks with his friends and does not want to be disturbed. In one pivotal scene, when his wife Irmgard (Irm Hermann) demands that he come home, he throws a chair at her. Later, when questioned, he beats her.

His family scorns him and thinks of him as a disappointment. They shun him after the case of abuse, siding with his wife while he beckons her to come back. The only person in his corner is his sister Anna (Hanna Schygulla), yet she has a minor role and is mostly ignored. When we see the family on screen, they serve the purpose of reminding us how worthless Hans is in their eyes. It’s no wonder that he feels such helpless despair.

Hans suddenly has a heart attack, and is forced to stop drinking and is not allowed any heavy activity. Given his prior anguish, one would think that this would push him further into depression, but the opposite happens. He takes on the role of proprietor, hires a productive employee, and enjoys profits. In a later scene, his family is surprisingly pleased with him. In their eyes and his, he has succeeded as a cart merchant.

Things come tumbling down due to another theme among the primary characters – weakness, especially in terms of their sexual proclivities. Han’s weakness with an admirer is what ruins his military career. In an early scene, he delivers fruit to an woman and is chastised by his jealous wife for spending seven minutes with the woman. We learn later that there is a hint of an affair happening at some point, which possibly happened off-screen during these early scenes. While in the hospital, Irmgard has an affair of her own with a taller, more masculine man. That man coincidentally ends up becoming Hans’ successful salesman. In my opinion, this was too coincidental, but it was a necessary plot development to take Hans further down in his slide.

Irmgard is a confounding character. She rekindles her relationship with Hans, even when he is employing her former, temporary lover. It is in this period that his depression begins to take shape again. Even before he discovers the truth, which comes up after he catches him skimming money from his sales, a strategy in which Irmgard suggested. She is the mystery. Fassbinder usually portrays women as strong and sympathetic characters, but Irmgard makes some baffling decisions. At times she seems to want to undermine Hans, while at others, like in the image above, she is saddened by his downfall.

Hans’ depression reaches such a low that he decides he wants to die. We learn through flashback that this is not the first time he’s reached this low of a feeling. When being whipped by an enemy soldier, he faces certain death, only to be rescued at the last minute by fellow soldiers. Rather than thank them, he asks them, “why didn’t you let me die?”

The final drinking scene is the culmination of the burdensome weight of all those who he has disappointed, including himself. Because of his health condition, he holds the gun that will decide his fate. He commits his suicide with bitterness and no regret. He even dedicates each shot to a certain someone who has wronged him. This is his way of getting back at the world.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements

Commentary – Wim Wenders, 2012.

Wenders talks about how it is unusual to comment on a film from a friend and colleague that died 20 years ago. He gives a commentary you would expect from Wenders. He speaks slowly and relaxed. He is not the type to comment or analyze every little scene. Even though I like analytical commentaries, I also like this type because it is more like you are watching the film from a friend.

- Fassbinder did everything himself, including writing, directing, sometimes acting, editing, sometimes producing. Working on so many projects as Fassbinder did required him to be working on the next one while he was finishing the last one. Wenders says that the speed in which he worked would eventually kill Werner.

- Wenders loves film, and he especially loved Hans Hirschmüller so much that he cast him in Alice in the Cities.

- He had such a strong ensemble that he would often cast his major actors in small roles. Hanna Schygulla and Kurt Raab are examples here. Of course Schygulla, in Wenders words, would “become one of the major stars of German cinema.”

- Back then, selling fruit off a cart was a real Bavarian profession. He points out the fact that the people speak with a distinct Bavarian accent, but that does not come across with subtitles.

- Prior to the German New Wave, the most successful German films were either Westerns or softcore porn. This direction into character-based melodramas was a major shift. They learned their craft from American films.

- He talks about the New German Cinema experience. They were not in each other’s way, had nothing in common, different perspectives, different missions. They helped each other, had no envy, shared cast and crew. Fassbinder was way ahead of them. By this time, Wenders had only made two short films. They were not bound by a cultural aesthetic, and never discussed content, style, but more about distribution, projects, etc.

Irm Hermann: 2015 interview.

She had no formal training, but got lucky when she met Fassbinder and he pulled her off of an office desk and put her in front of a camera for The City Tramp. He quit her job for her. Fassbinder was charismatic and started in the theater. She had no training save for how Fassbinder trained her. She didn’t want to do the sex scene, but Fassbinder was discrete and sent everyone out of the room. She is grateful for the film because of the Douglas Sirk-like close-ups. Her and Hirschmüller won German Awards, as did the film. and that was a major deal.

Hans Hirschmüller: 2015 interview.

The role of Hans was written with him in mind. Fassbinder wanted someone down to earth and simple, which was really what he was at the time. He knew the types of merchants that he would play. Fassbinder didn’t tell him anything about the role. He just made him read the script, and asked if he approved.

They did not often do multiple takes. Usually one or two, sometimes three, but very rarely four. Rehearsal is when they would improvise, never during the scene.

It was a tough role for him because he had to face death like he never had in his personal life. He had trouble getting to the position of being helpless. The scenes where he was depressed were the toughest for him.

Eric Rentschler: Interview with film historian and professor at Harvard.

This was the film that put Fassbinder on the map. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive. Some said it was the best film to come out of Germany in years. Fassbinder had been working productively prior to this, but his rise out of Merchant was meteoric. Early films were bleak and resembled neo-noir. You could tell that Fassbinder was a student and fan of film.

Fassbinder is good at showing what character’s are capable of, both good and bead. Irm Hermann is an example of this because she has adultery and is planning on leaving her husband on one occasion, yet adores him in other occasions.

The film was based on his uncle, who had fallen from a high position and ended up as a fruit salesman.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

The Great Beauty, 2013, Paolo Sorrentino

Believe it or not, this was my third time giving The Great Beauty a chance. The first two times I hated it. In fairness, both of my previous two attempts were not during the ideal circumstances. The first time was on Video on Demand before the home release. I didn’t realize the movie was as long as it was, so I had to cram it in during a busy time before the 24-hour rental period expired. It seemed beautifully shot, but overlong and plodding. The second time was when it was on Netflix instant, before the Criterion release and before I knew I’d be undertaking this ambitious project. That time my take was similar, but I watched it when I was tired and felt it was an inferior La Dolce Vita knockoff. My love for Fellini fueled my hate for Sorrentino.

I bought the Criterion because I buy all of the Criterion Blu-Rays, but it was one I planned to save for a rainy day. Maybe I would watch it last. I decided to try again after talking with Mikhail from the Wrong Reel podcast. I respect his opinions and often agree with him (although not always). He said he considered it to be one of his top 20 films of all time. Really? That was a surprising statement. He also would have La Dolce Vita in the same top 20. That was even more surprising, because I know some other Fellini fans who also despise The Great Beauty. Since I had revisited La Dolce Vita since my last attempt at this film, I figured it would at least be an interesting experiment in contrast, but I did not expect my mind to be changed.

My mind was changed.

The beginning of the film is absolutely exhilarating. I thought that on all three viewings, but it especially took hold of me this time. The film begins in daylight and the camera cuts quickly between gorgeous Roman buildings and vistas, intermingled with shots of random people. We see a Japanese tour group, and one of them dies, which introduces two themes that will come back later – tourism and death, and this moment will be subtly recalled at the end of the film. The camera is rarely static, and instead moves quickly, reminding me of Wenders’ Wings of Desire that gives the sequence a constantly flowing feeling.

Daylight abruptly ends and night begins as we are transported to a vibrant party, introducing a contrast that will continue throughout the film – the splendor of Rome during the day versus the wildness and debauchery at night. The camera moves just like it did in the daytime, with the same type of quick cuts. We see random images of participants, a motley crue of characters, some of whom will return later and some we will leave with the party. The party is a way to memorably introduce the main character.

Hello, Jep Gambardella! When we are introduced to Jep (Toni Servillo), he is clearly in his element. He dances to the hypnotic music, has a beaming smile, and soon will randomly French kiss one of the beautiful women. This is his 65th birthday party, and although he has the gray hair, he acts like someone half his age. He is a partier, living for the nightlife without a care in the world. He is affable, casual, fun loving, and we immediately understand why such a huge crowd flocks to his party. He’s the kind of guy people want to know, and even at 65, the kind of guy that people want to be.

I cannot write this without highlighting the similarities between Jep and Marcello from La Dolce Vita. They are both journalists. Marcello wrote for gossip magazines, whereas Jep interviews various figures from performance artists to religious figures. Jep is the more prestigious writer, both presently and in his past, having written a novel (or novella, as it is sometimes referred) forty years ago that sounds to have reached a level of popularity and literary credibility that Marcello was not within sniffing distance. They both are having an aging crisis, although Jep’s has more to do with being close to mortality, whereas Marcello is having a mid-life crisis. They both live for the night. In both films they go to parties and gallivant around Rome at night.

The similarities end there. Marcello is a bitter individual, whereas Jep upbeat, yet cynical about life and society and can be caustic, particularly when he verbally takes down a fellow, hubristic writer. They are both charismatic and well liked, but Marcello is downbeat and soft spoken. Jep has his somber moments, but even when he is questioning his place in life, he still carries himself with composure and is not nearly as aloof as Marcello. It is also worth noting that in both films, the writers encounter a young girl. The one that Marcello meets is fond of him, and does not see his bitterness, whereas we barely even see the one that Jep encounters. She is underground and Jep speaks to her through a sewer grate. She tells Jep that he is nobody.

There are a few other filmic elements and plot points that evoke memories of Fellini, and I was surprised to find in the supplements that the filmmakers were not consciously updating Fellini. I’m not saying they are being disingenuous. Perhaps these similarities were accidental or unconscious, or maybe they are just being coy about their inspiration. Either way, I think it is fair to make comparisons.

Despite these few similarities, many of which are either plot and character broad strokes, and others that are minor details, The Great Beauty deserves to be viewed on its own artistic merit. It makes many prescient statements and observations about modern life and society.

One reoccurring plot point is the art world. Along the way, we meet a few modern performance artists. One of them is a child who hurls paint cans at a canvas while having an emotional episode. One spectator complains at the exploitation, and is told that she makes millions, implying that commerce is the inspiration rather than passion. Another performance artist begins with knife throwing around a woman. At first the worry is for the woman’s well being, and then when she walks away, we see that the knives left an artistic imprint on the wall. This combination of a carnival act and the art world is important, and would be recalled later.

There is one scene where a man discusses with Jep how he will hide a giraffe. This act is not magic or art, but unequivocally a carnival act. He reveals that it is just a trick. Earlier in the film, a performance artist hurls herself at a stone column and smacks into it head first. This is just part of her performance, but is the most memorable as it appears that she has physically harmed herself, drew blood even, and all for art. It is later revealed that she had a buffer that prevented her from harm, so this was just also trick.

Jep sees these artistic demonstrations during his professional or social sphere. When the sun comes out, another form of art is revealed – the architectural beauty of Rome. Some of the film’s “great beauty” is revealed either during sunset when Jep is beginning his nightly adventure, or when the sun has come up after his night has ended. What he sees on his solo journeys is real beauty, real art, and not artifice.

A moment that is striking both for Jep and the viewer is when he encounters another piece of modern art, but he stumbles onto it by accident during one of his daylight strolls. This piece of art is simple, just a number of small snapshots of the same person on different days. It does not sound impressive by description, but the large number of these pictures as a whole reaches a magnitude that makes it a larger, and more distinct artistic statement. This is life and it is beautiful. You could say that the art itself is a trick because it is comprised of numerous little photos, easy to produce individually, but the end result is something special. The difference is that it has no commercial motive and someone like Jep can wander by it without paying anything.

The film touches on a number of other subjects and themes that I could write thousands more words about, such as the nature of death, love, tourism, classism, resistance to aging, religion, and plenty more. On this third viewing, I saw a dense and complicated film that is about various forms of beauty. “The Great Beauty,” however, is just a trick.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Paolo Sorrentino: 2013 discussion with film scholar Antonio Monda.

Monda talks about meeting Sorrentino when accepted One Man Up for the Tribeca film fest’s first year. Scorsese asks Monda to call him because he was Italian, and it happened to be on April Fools Day so Sorrentino thought it was a joke.

Jep was intentionally supposed to be a likeable and casual figure, who had a cynical outlook on life and the world. They had seen people like that in Italy (particularly Naples) and it was not a tough character to envision. The “medium long” hair was a negotiation. Sorrentino wanted it longer.

They talk about the parallels with La Dolce Vita, and Monda wonders whether the broad stroke similarities were conscious. Sorrentino says they were not conscious. He says the only one that was intentional was filming the Via Veneto today. He says that the other references are unintentional, but perhaps subconscious because of his affection for Fellini.

The film is 137 minutes, which is long, but the first cut was longer. He misses those cut scenes and liked the first cut of the film, which was 190 minutes. He was not made to cut the film, but he did it himself. He thought that a long film would be exhausting, and it would perpetuate the theme (my words) that life is exhausting.

Toni Servillo: 2013 Criterion Collection interview.

This was his fourth film with Sorrentino, and he acknowledges that he owes a debt to the man for making his career. They share many ideas and observations, which made their way into the lead character. Paolo even designed the wardrobe, which was based on a Neapolitan tailor. Paolo wanted his Neapolitan flair to be very evident and clear, and not something he tried to conceal.

One thing I loved about this interview was not the words spoken, but the bookshelf behind him. There were books on Selznick & Hitchcock, Zanuck, and African Film Music. Servillo is not only a participant in film, but also a connoisseur and admirer.

Umberto Contarello: 2013 Criterion Collection interview.

Contarello is the screenwriter that worked with Paolo, and like Monda, met him at a festival. Some of his comments are redundant from the Sorrentino interview because he talks about them working together on a film that did not end up getting made. They developed a rapport during this collaboration.

When he heard about the scope of the project, which was Sorrentino’s accumulated thoughts about Rome, he said thought the project was ambitious, but Contarello also had thoughts on Rome that he could add. So they went to it. They did not intend to write a complex film that was a critique of modern society, so they intentionally added dimensions to Jep from things they liked about writers. “He seems fresh off the boat from Napoli” because of the way he moves around the city, but they portrayed him as if he lived in Rome for years.

They approached Fellini as an archetype on an unconscious level, basically repeating Sorrentino’s remarks. He compares this to The Odyssey, and that basically every film about a journey is inspired by Homer to a certain degree. A film about Rome cannot help but draw from La Dolce Vita

Deleted Scenes:

Maestro Cinema – Jep visits an aging film director in this short scene. The character has made a lot of films that said little of importance, and wants to make a film that says something. The director is the opposite of Jep.

Montage – This is a two-minute collection of deleted scenes. I’m actually glad they did not include the entire long cut, even if the scenes were good (and they do look good), but that would have been too much. Sorrentino was right to cut this film down. That said, one day I would like to see the longer film.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

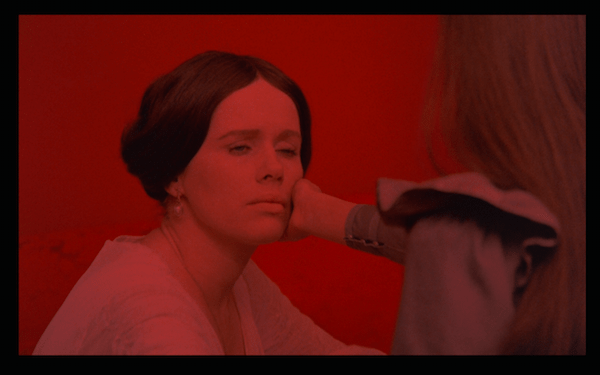

Cries and Whispers, 1972, Ingmar Bergman

By 1972, Bergman was already established as one of the titans of international art cinema. He had won several awards at Cannes and been nominated for two Academy Awards (he would eventually be nominated for 9, including three for this film). Cries and Whispers is not a film that could be made by anyone. It could not have been made by Ingmar in his younger years. It could be seen as a spiritual sequel to Persona, which was really his first foray intro surrealism and immersive, abstract character exploration. Cries and Whispers does not share many thematic or plot elements with this predecessor, but it does utilize the supernatural and it explores these four characters nearly as deeply as the two (or one?) in Persona.

Another similarity between this and Persona is the visual canvas. Persona was in black and white, but I think of it as starkly black and starkly white, almost to the point where it has the same effect as a color film. Cries and Whispers is a color film, but it is nearly a red and white film. The reds are stark and stunning, while the whites are a contrast, just like the whites were in Persona. The colors are visual motifs as well, as red signifies death, mutilation, and white represents the innocence of a lost and nearly forgotten childhood. Sven Nykvist rightfully won an Oscar for his work, and Bergman and crew deserve praise for creating such a visually remarkable red-and-white world.

The color of red is used most effectively for the scene transitions. At the end of a scene, the image dissolves into a red canvas, which gives it a surreal quality. It is a continual reminder of the central theme of death, as Agnes fights her battle with uterine cancer. Sometimes Bergman freezes in the middle of the dissolve, holding on the blood red screen to give us time to ponder and process the meaning of the scene. These transitions and the slight deviations with each one heightens the impact of the color red. I can think of many movies that have used a single color to dictate the theme, some of which are done well (Kieslowski’s Red for example), but none that used it to this extreme, creating what is basically a red and white film.

Please be warned that from here on our I will be delving into spoiler territory.

Harriet Andersson as Agnes gives the most memorable and challenging performance as she tries to cope with the pain and her imminent, unavoidable death. The anguish on her face is heartbreaking and convincing. Much of her performance is given in grunts and grimaces. She is at her most vocal at the very end of the film, but this is after she has passed and the pain has left her. Only the loneliness and the yearning for comfort remains. She seeks solace from her two sisters, yet receives it only from her housemaid Anna (Kari Sylwan) in an unusual yet effective manner.

The sisters, Maria (Liv Ullmann) and Karin (Ingrid Thulin) are complicated characters, at times polar opposite from each other, yet there is some grey (or red?) area in between. To her sisters, Karin is stoic and stubborn, refusing and being repulsed by intimate contact. Maria is affectionate and compassionate, yet she is unscrupulous, making out with the doctor watching over Agnes. In flashback we see Maria and the doctor having an affair, which results in her husband attempting suicide. Karin also flashes back, but her memory is of fidelity and mutilation. She says “nothing but a web of lies” as she abuses herself with broken glass and then exhibits a grisly scene for her stunned husband.

At Agnes’ funeral, the priest says that they had many talks and her faith was stronger than his. Is this why she is able to come back? This is never explained, but the ensuing revisitation with Anna and the sisters has differing results. Maria, who was affectionate to Agnes in life, rejects her in death. Karin also rejects and hates her resurrected sister. Again, the only character that gives her any comfort is Anna, yet the living relatives treat her with scorn and dismiss her as if she was a piece of trash.

The film can be interpreted a number of ways. It speaks to the intimacy (or lack thereof) of family, and how familial love and companionship is fleeting and unobtainable in later life and especially in death. It speaks to the wickedness of the upper class, and how true camaraderie and goodness comes from those that are not clouded by a privileged upbringing. It also says that personal relationships are ultimately rooted in selfishness. With their husbands and other sisters, the sisters care only for what they receive. The same is true about Agnes, who we learn little about, but she is also selfish for intimacy and companionship. The only true altruistic and benevolent character is Anna. She pledges to care for Agnes in life and in death with no financial recompense. At least Maria, who despite her flaws is the most considerate of the other primary characters, and gives Anna a little something to help. Maybe there is hope for humanity yet.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Bergman Introduction: 2003 on the Island of Fårö.

This project came about in winter on the island. It was melanchology time for him because he had just been broken up with someone. He was lonely with only a Dachshund to keep him company. He had an image of a room completely in red. He believes that if the image persists, you should keep writing.

Harriet Andersson – 2012 Stockholm interview with Peter Cowie.

This was just like the interview on the Summer with Monika disc, and was probably recorded in the same session. Harriet was again very animated and descriptive. She is a great interview at an older age.

It had been 10 years since she had worked with Ingmar. At first she rejected the part because it was too difficult. He said, “Don’t give me that load of crap,” and she took it.

The castle set was wonderful. They had offices downstairs. The red rooms were the studio on the main floor. The floor above was for make-up and wardrobe. Ingmar had said the red room resembled the inside of the womb. Andresson: “Well he says things.” “He like to make small stories.” She implies that he is telling a tale.

They kept her awake at night and that made her look tired. The death scenes were an imitation of her father, which she witnessed. He had a terrible death. She has trouble watching the film now because of that memory.

On-set Footage Silent color footage with audio commentary from Peter Cowie.

This is the highlight of the disc. They have quite a bit of silent behind the scenes footage that includes the set-up, press conference, actresses on location in and out of the house, the cast and crew being fed, editing of the film, rehearsals, and so forth. It is a wealth of material and Cowie gives numerous factoids on the film just by talking over the images. This was almost as satisfying as a good audio commentary.

They talk a great deal about the playwright Strindberg. He had spent summers at the manor that they used as a boy and took inspiration of Miss Julie from lady of the manor. Bergman had adapted Strindberg plays for stage, but never for film. One interesting point is that Bergman’s films were not very popular in his home country, but his Strinberg plays were exceptionally popular.

Ingmar Bergman Reflections on Life, Death and Love: 1999 television interview with Erland Josephson.

This is another enjoyable interview. They do not talk about the films so much as they do personal lives, loves, relationships, and various other topics. Bergman is surprisingly candid.

They talk about children. They both have quite a few (Bergman has nine). Bergman talks about apologizing to one of his children for being a terrible father, when the son says that he hasn’t been a father at all. They all get together every year at Fårö Island and the children have maintained good relationships. None of his children were planned. “They were all love children.”

The women lasted about 5 years until he found a new one, and then he found Ingrid, and then she died. When she decided to marry him, “all other traffic ceased.” He was truly in love. He is friendly with all the other girls that he was ever with, and many (including Liv and Harriet) became part of his acting stable. Elrand points out that all the bitterness subsides over time. With Ingrid he had a close relationship, and he has reverted to solitude now that she’s gone.

They talk about death and the inevitability, and how Ingmar doesn’t fear it so much but Elrand does. Of course he talks about Ingrid and how he planned to leave Fårö to her, but her passing happened and it crushed him. You can tell that his life was still devastated by it even all those years later.

On Solace: Video Essay from :kogodana:.

This is an interesting essay, unlike most on Criterion discs. It uses images and text well, especially the red title cards with white text.

The concept of the three movements is abstract to a degree, and it is easier to watch than for me to explain it here. Basically he says that there are three movements. The first two movements are flashbacks, while the third is a distillation.

He points out a few insightful observations, such as that Karin’s mutilation is inverse of Agnes’ uterine cancer. The final scene recalls “bodily solace” that Anna gives Agnes in earlier scene, which is the central theme of the movie and the thesis of his essay.

Criterion Rating: 9/10

Summer With Monika, 1953, Ingmar Bergman

For this post I am mixing it up a little bit. Rather than do a formal review, I’m participating in MovieMovieBlogBlog’s Sex! Blogathon. Rather than do a formal review and/or analysis of this earlier Bergman film, I’m going to explore how sexuality was portrayed and how revolutionary it was in the world of cinema.

Monika and Harry are like many young, lusty couples. We see the courting process with them watching a romantic movie together. She is in tears while he yawns, which is typical, but through their brief time together they establish a deep, romantic connection. From there they escalate to a sexual relationship.

Even though Bergman had not launched on the internal stage just yet as a major auteur, by 1952-53, he had honed his filmmaking craft. The film language he used in films like Summer with Monika and previously in Summer Interlude would remain relatively constant throughout the rest of his career, but of course he improved and became more capable over time. He also showed early on a keen ability to demonstrate romanticism, sensuality and even sexuality. Because of the Hay’s code, American filmmakers had learned the power of suggestion through film language to hide the overt sexuality in film. Bergman borrowed some of these hints and developed a few methods of his own, but he also not afraid to dip his toes in the water and explore sexuality more directly.

We know that Monika and Harry begin an attempt at escalating the physical relationship because they are in the midst of some heavy petting when her father comes home. They quickly dress and act as if nothing was happening, which is a subterfuge that many (probably even Bergman) can identify with. They then meet on the boat and presumably have sex. They are in the same bed and there are vague suggestions at sexual activity. Harry loses his job and does not care. His new job is within the arms of Monika. As he ventures away from the city with her, we see the city from the boat’s point of view. The camera rocks back and forth, which we would expect from a floating boat, but in my opinion it is rocking because of the activities taking place within. Later in the film we learn that Monika has become pregnant. Conception most likely took place during these early scenes.

The sexuality transforms from suggestion to depiction as they reach the island. We first see Monika wearing a revealing bottom and a loose shirt, which she takes off. This is only the beginning of a series of scenes with a scantily clad Harriet Andersson. As they settle on the island, we see what is quite close to nudity. She faces Harry and removes her top, revealing her nude back. We then see her from Harry’s perspective, but his body blocks any nudity from showing on camera, yet his wandering hands clearly reach those same hidden areas. Monika gets up and runs to the beach and we see her naked behind, and then the film cuts to her in a natural pool. This scene is tame by today’s standards, but for 1953, it was quite scandalous.

The relationship and plot play out over the summer, and since this is not a traditional review, I’m going to skip these details. As they get settled back in the city, Monika becomes weary with her relationship and strays elsewhere. Bergman communicates this by simply having her look at the camera seductively when we know she is out of the house and away from Harry. This was also scandalous, because this was a sexually licentious woman. People in film were not often portrayed as straying from a committed relationship or marriage, even if it was only hinted at (although confirmed later) like in Bergman’s film.

In one of the final scenes, Bergman goes for the gusto. We see Harry raising his little girl, betrayed and rejected by Monika, but that summer still enraptures him. It isn’t clear whether the sexual escapades or the romantic moments are the most magical in his memories, but the version of Monika in the summer was a fairy tale. We see a flashback from his perspective of Monika in the same near-nude sequence as earlier, but this time the film does not cut as she runs to the beach with her rear exposed. She is fully nude, although this is a long shot so, again, not very explicit to modern eyes, but progressive for back then. Given that Harry remembers that one, erotic image, I think it was his personal sexual revolution that he longs for.

Film Rating: 8/10

Supplements

Ingmar Bergman Intro:

This is a brief introduction from 2003. Bergman felt affection for the film because of the way the screenplay came together, but also because of his introduction to Harriet Andersson. He had seen her in a stage play in fishnet stockings and lace, so he wanted her to be in the part. He did not go into the fact that they became lovers.

Harriet Andersson: 2012 Interview with Peter Cowie.

It had been 60 years and for her age, she looked remarkable. She speaks English well, with a strong accent. She talks about her origins in the industry, from being picked out to working with Bergman.

Bergman’s reputation in Sweden was very poor among actors at the time. He was reputed to yell and scream at them, and had his eye on young girls (which isn’t entirely inaccurate). She auditioned with an 8-minute shot where she was sketchy with her lines. She was surprised to get the part, which was a dream part.

She was not worried about the nudity. They were on an island so it felt natural, and the crew had seen it already. It felt liberating.

They talk about her looking at the camera, which was a scene that was appreciated by the French New Wave. She was shocked at the scene at first because this was something that wasn’t seen. People didn’t look at the camera. She thought it was strange, but went along with it.

Because of being lucky in getting this famous role, she was able to get roles with other directors and of course many future Bergman films. It was a break-out role for her.

Images from the Playground: .

This half-hour documentary is introduced by Martin Scorsese, who produced it through World Cinema Foundation. He was fortunate enough to live through Bergman’s career genesis from Summer with Monika up to Saraband. The documentary has behind the scenes footage from Bergman working on the film. It is from Bergman’s 9.5mm camera, and is almost like a home, silent video. It has narration from audio interviews of Bergman and his stable of actresses.

They talk about the production, such as Bergman discovering Harriet and talking about how gorgeous she was. It is interesting to see this commentary, but it is easier to just get caught up in the images and narrative. They take the documentary beyond just Summer with Monika. Bibi and Liv also participate. Bergman talks about the importance of all of these actresses and there are reflections on the fact that Ingmar was involved with them intimately at some stage.

This really is a magnificent little piece of film. It is the treasure of the disc.

Monika, Exploited!

Summer with Monika was a controversial picture in the states, and was hacked up and released as exploitation-fare with an English dub. This is an interview with Eric Schaefer who talks about how it became exploitation fodder.

During post-war period, distributors were importing films from overseas with adult content. These arthouse films were released in the exploitation circuit. Monika fit well with this market because of the brief nudity and sensuality.

Kroger Babb, an exploitation exhibitor, got the rights to Summers with Monika for $10,000. He then put in $50,000 into the film for cutting and dubbing. He got it through deceptive and suspect means, and Svensk took legal action because they soid the rights to Janus Films. They worked out a deal to release “Stories of a Bad Girl,” Babb’s version for five years, while Janus would release it for art audiences.

Criterion Rating: 8.5/10

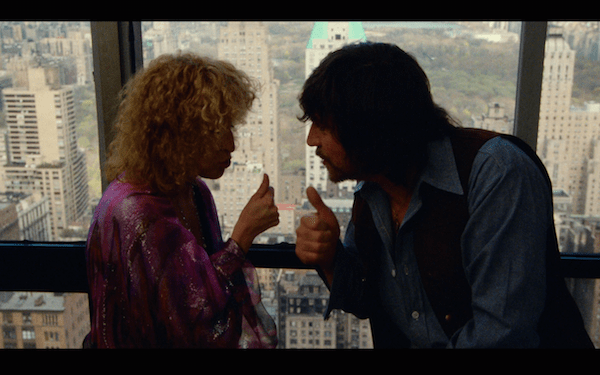

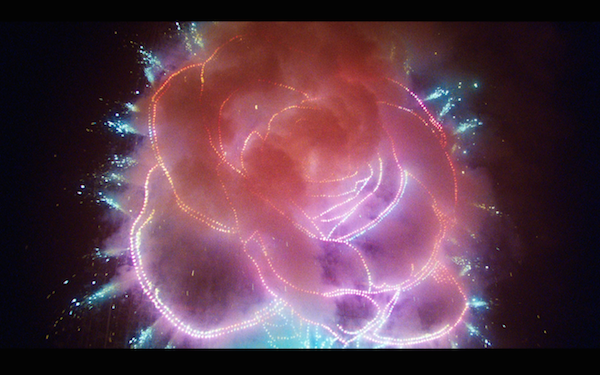

The Rose, 1979, Mark Rydell

I have been aware of The Rose for most of my life. People had talked about it at various stages, but I made an unconscious decision not to see it. Why? Maybe because I loved Janis Joplin and disliked Bette Midler, so the burning desire wasn’t there. It wasn’t anything about Midler’s acting ability or talents, just that I was certainly not the target market for the remainder of her career. The fact that it was not really about Janis turned me off more than anything else. Having now seen it many years later, I’m actually glad I waited.

First off, this is not about Janis Joplin. In many of the supplements, this is stated and re-stated, and it is unfair to the film to get hung up on her life being the template for the plot. It is only the broad strokes that relate to Janis. This film is about the plight of the rock and roll star, the insatiable need for the rush of attention that one gets onstage, the insecurity off the stage, and the self-destruction in between. The only time that Janis is recollected is in the performances, yet not all of them. Most of the performances are all Bette channeling a 70s rock-starlet persona.

What stands out about the film is the cinematography. From the early scene in a building that towers above Central Park in New York City, to the kaleidoscope of images and colors that are captured in the live performance, every frame looks fantastic. Vilmos Zsigmond is responsible for the majority of the film’s appearance, but he also recruited some of the best in the industry to capture the concert sequences. Rather than go into specifics, I recommend you read Adam Batty’s post about The Eyes Behind The Rose.

The Rose shouts out at a concert that she keeps herself in shape through “Drugs, sex and rock n’ roll!” The order in which she places the words is telling. Most people refer to that era as “Sex, drugs and rock n’roll.” One of The Rose’s problems was that, despite her fame, she was not able to “get laid.” She expresses this directly in the early meeting with Rudge (Alan Bates). We don’t see her delve deeply into drugs until towards the end, which is what initiates her downfall, but the sex and subsequent rejection leads her to search for an escape. Rock n’ roll was last on her priority list because it really was. She was exhausted from all the touring and performing, and desperately wanted a break. Her mental stability was wearing down due to the lifestyle, yet Rudge trapped her. Her desire for the limelight and attention also trapped her. In many ways, rock n’ roll was her drug, only it was not giving her the same high it did before.

Deep down, The Rose simply wants to be appreciated. She’s shy, insecure, and in a lot of ways neurotic. The stage is the only place where she really belongs, where she feels appreciated. One recurring theme is her constant rejection. It begins with Billy Ray (Harry Dean Stanton) not so politely asking her not to sing his songs. Later in her hometown, she is recognized in a familiar shop owner in her hometown as Mary Rose and not “THE” Rose.

Redemption comes her way through Huston Dyer (Frederic Forrest), a limo driver who she steals from Billy Ray and takes on a wild misadventure of sex and shenanigans. Huston, however, is from a different world. He’s actually a deserter from the Army, and cannot relate to the “drugs, sex and rock n’ roll” lifestyle. What they have in common is that he is a deserter, and she wants to leave her rock career at least temporarily, and into his arms seems the most appropriate place to hide. Huston does not approve of what she’s doing to herself, and this comes to a head in the powerful bathhouse scene where he finally lets loose. He comes back to the fold, but the old magic has gone.

The Rose is a mess. “Do I look old?” she asks at one time. She is yearning for any sign of vitality, yet she finds none unless she is on-stage. The breaking point is when Rudge strong-arms her as a power contract ploy and cancels her hometown show. This smoking gun transforms her from a slow descent to a spiraling downfall. She takes solace in every chemical she can find, trying to find a chemically induced feeling that rivals what she feels onstage or in Huston’s arms. When some demons come back to haunt her, she finally caves, only it is too late. The damage has been done. That is the tragic reality of some rock n’ roll lifestyles. Again, even though this movie was not about Janis, her tragic reality is the backbone. The Rose’s downfall is just as tragic, even if fictional.

The performances are truly what makes the film worth watching. Midler owns her role as The Rose, and I was impressed that the star of Beaches was able to convincingly play a rock n’ roll star. Forrest as Huston also shines in the scenes where he gets to be the voice of reason. Even Alan Bates as Rudge does a fine job with what is essentially a flat character. Some of the dramatic choices are a stretch and at times the film gets heavy-handed, but overall it is a worthwhile character exploration.

Film Rating: 7/10

Supplements

Commentary: Mark Rydell from 2003.

- The band was put together with Rydell, Paul Rothchild, and Bette Midler. They were a real band that played real stories.

- This was NOT the Janis Joplin story as Rydell emphatically states. It was a character based on some of the rock stars in history. It was conceived as biography of her for years. They made a fictional character using the dramatic elements of Joplin’s life that were dramatic and fitting, and invented the rest.

- They shot real concerts, twice at two hours without interruption. There were no interruptions and Bette was really playing to the crowd. These shows were later cut together for the film.

- Bathhouse scene was unheard of. All that male nudity, even if not shown, was shocking for the time.

- Rydell spends a lot of time gushing about the actors. They all exceeded his expectations.

One thing I like about this commentary is that Rydell lets the film breathe. He stays out during important moments, so it’s almost as if watching the film again. He interjects only when he has something worth saying. Sometimes I prefer this sort of commentary to one with endless chatter.

Bette Midler: Interview from 2015.

At first she didn’t want to do it. She was a Joplin fan and didn’t want to tarnish her legacy, so they changed it from being inspired by Joplin and not telling the complete story. She started gymnastics for her stage moves. Wanted to get a panther quality to her moves, “a violent creature” on stage.

She praises Forrest in particular. She thought he did a great job at being patient. She wasn’t prepared for Harry Dean Stanton. He was tough. Everyone wanted her to succeed (except for Harry Dean.) They were supportive, and it was “joyful and full of love.” She remembers it more than most of her movies.

Mark Rydell: Interview in 2014.

He also didn’t want to do a straight Joplin biopic. People recommended Bette Midler and he knew she was perfect when he saw the dailies. She had sung in men’s bathhouses, so they incorporated it into the movie.

Aaron Russo was her manager and was very controlling. “You talk to me before you talk to Bette.” He called the police and got him out of there. Bette got him out of the way then and that began his relationship with Bette.

He talks at length about all the amazing Directors of Photography that he used for the concert footage. He needed nine cameras for these scenes. He asked Zsigmond to pick the best cameramen in town, and somehow he succeeded in getting the the giants of the era.

There were 6,000 people at the concert, who came out because of a radio announcement. They were told not to react unless the performer makes them react. She brought it. “That’s why the concert felt so alive, because they were alive.”

Vilmos Zsigmond: He speaks with cinematographer John Bailey in 2014.

The opening shot was in the Hilton in downtown NYC. It was difficult to light because they had to be careful of the backlighting in the windows.

Of course he also talks about the concert scenes. They lit them differently because they shot them on the same stage. They did the overhead helicopter shot, carefully lit it up, and did so to show the popularity and stature of The Rose. They did a lot of improvising with the shots because the performances were improvised. In addition to the star cinematographers, he also used Dave Myers, who was a big concert photographer, who famously shot Woodstock.

He thinks that the craft is diminishing, and that the concept of lighting is being lost. Too many people are becoming cinematographers. He is trying to teach the youngsters that are using digital cameras to go look at the old films, see how they are lit. Don’t get lazy by how easy the digital camera is to use.

Today Show: Tom Brokaw with Rydell and Midler in 1978.

It shows behind the scenes of them shooting the scene where she leaves a news conference, take after take. Brokaw interviews Rydell and he gives overwhelming praise to Midler for her performance.

Gene Shalit & Bette Midler: Interviews from 1979.

He asks the question about Janis Joplin, comparing the fact that Janis is 1960s whereas Bette is 1970s. Bette said that she did not intend to become Janis. She contrasts the differences. She is a New Yorker, which is a bombarding culture, but she played a Californian, which is more of a laid back atmosphere.

Janis Joplin, Tina Turner and Aretha Franklin inspired her. She saw them all in the same week in the 1960s and that was the turning point.

It is interesting hearing her reflect on her career, which is something she had just started thinking about recently. She says she would be happy if she retired tomorrow. Of course there were would be plenty more to come.

Criterion Rating: 8/10

Modern Times, 1936, Charles Chaplin

In many ways, Modern Times was both an ending and a beginning. For Chaplin, it was the end of his silent movie star career and his popular character, the tramp. It was also the last major silent film release. It was at the height of the depression, and the underlying themes represented Chaplin’s critical feelings of industry and the exploitation of the working man. Little could he know that everything would change in a few years with a war, which would devastate the world and end the depression. Yet, the changing times did not date the picture. With historical perspective, Modern Times can be seen as a nostalgic and sentimental transitional film.

If there are any questions about Chaplin’s thoughts about industrialization, then they are answered within the first 15 minutes. Chaplin effective turns a social issue (one that we felt strongly above) into comedy, and as expected, he was completely successful. The early factory scene delivers the laughs. Chaplin becomes both obsessed and complacent with the act of riveting. Occasionally he’ll sneeze or otherwise be forced to miss an item and the assembly line will go out of whack, forcing the two other employees working behind him to get frustrated with his antics. The Tramp keeps on turning knobs with his two wrenches, sometimes even when his hands are not over the assembly line. He gets distracted by a woman’s attire with dark, loud buttons, and tries to turn them too. This scene works flawlessly. There are not many cuts, so the action must have been carefully rehearsed and difficult to carry out, and the speed at which the scene flows thanks to the customary 16 frames per second in silent films make it seem all the more hurried and manic.

The scene with the most laughs, at least for me, is the lunch efficiency machine. Again, Chaplin is poking fun of industrialization, specifically the fact that they value production so highly that they will compromise the worker’s free time and convenience by automating their lunch process. The machine dumps soup on Chaplin, forces him to eat corn on the cob at a rapid fire pace, and smacks him on the face when it is intended to merely wipe his chin. The device itself is funny simply due to its absurdity, but it is Chaplin’s performance that cements the scene as being so memorable in his cannon. He recalls the lunch machine later in the film by becoming a lunch machine himself, yet he is just as effective (or ineffective) as the automated version. Again, this is funny, but he is still making a cultural statement. People do not need external assistance, whether from a machine or a human, to perform basic duties.

Chaplin’s politics seem clear in some instances and hazy in others. He is clearly portraying modernity from a leftist perspective, and that echoes some of the activism he was undertaking outside of the film industry. However, he was careful not to go too far to the left. There is another scene where he takes a flag from a truck. A communist mob marches behind him, and he is swept up with them. As the flag waver in the front, he is mistaken as the front-runner in yet another hilarious gag. Despite the scene’s humor, he is distancing himself from the Communist movement. He was leftist, but not that left wing.

Unlike other Chaplin pictures, in Modern Times he has a co-star – a trampette if you will – in the form of Paulette Goddard, his off-screen lover. Even though Chaplin is always the funniest, she provides a welcome equilibrium to his antics, along with a motivation for him to pursue his character arc. Before meeting her, he was perfectly content being in jail because, after all, they served food and gave him a roof over his head, which wasn’t always the case on the outside (and this was another comment about modern times.) After meeting Goddard as The Gamin, he wants to succumb to the lures of society. He wants a good job so that he can afford a nice house, even if his dream house still rejects modernity by extracting milk directly from a passing cow rather than buy the processed product.

As Chaplin and Goddard pursue normal lives, and even find themselves living in a crude, fragile shack, they cling more to a life of poverty. In Chaplin’s vision, having less allows one to live in opposition to the modern trappings of society. They find themselves in plenty of other comic scenes, including a department store and most famously, a restaurant where Chaplin sings for the first time, but this is not the life for them. As everything they aim for falls apart, they are content simply walking away, hand in hand, comfortable in each other’s company.

Film Rating: 9.5

Supplements

Commentary:

- Modern Times definitively identifies Chaplin’s transition from silent films into sound. He had intentions of making a talkie and even wrote a script, but trashed the idea after filming a couple scenes.

- After City Lights, he went on an 18-month world tour where he was treated as a celebrity. He saw economic collapse and nationalism. He published a number of social articles when he returned, including those about the tyranny of the assembly line.

- The lunch machine scene took 7 days. It isn’t known for sure because Chaplin never revealed his methods, but it is thought that there was an operator somewhere, although stills show Chaplin operating the lever.

- He was accused of ripping off Rene Clair’s À Nous la Liberté. Some argued that the similarities were obvious with any industrial story. Clair was not pleased with the lawsuit because he respected Chaplin. He didn’t think Chaplin was guilty, and if so, was flattered. The suit was out of Clair’s hands and went on. It didn’t resolve until 1947, where Chaplin paid a modest settlement.

- Goddard had been a struggling actress and a divorcee when she met Chaplin, when their affair and collaboration began. He convinced her to go back to her natural brunette color instead of the platinum blonde.

- One of the few critical complaints is that Modern Times is a series of 2-reelers, which is true to an extent (factory, furniture store, factory again, restaurant).

- Like City Lights, he was credited as composer. People have criticized him for taking too much credit away from his arrangers. He could play instruments, but could not read music. The arrangers all confirmed that he directed the compositions through them.

- The FBI, trying to establish a link with him and the Communist Party, investigated Chaplin. It was more that he found left leaning individuals to be better dinner companions. The FBI never found anything despite their pursuits. He was never tied to the party, so their efforts were futile.

- Chaplin’s song became famous. In 1939 it was released as a song about who had the better mustache, Chaplin or Hitler. It was most famous as being the first time his voice is heard on screen. He sings a gibberish of his own invention.

Modern Times: A Closer Look: Visual essay from Chaplin historian Jeffrey Vance.

Chaplin was highly secretive about how he worked. He did not allow people to film him during the process. “If people know how it’s done, the magic is gone.” Still photos survive as the background of the making of Modern Times.

He spoke with great minds (Churchill, Einstein, others), and wanted to make some sort of social cinema. He nixed the idea of a Napoleon film when he befriended Paulette Goddard. This would begin an 8-year collaboration with Chaplin and Goddard, which included a common law marriage. They treated each other as equals, and he cast her in that manner in the film.

The film was steeped in the political and social realities of the time. He met Henry Ford in 1923 and found that people who were hired from farms to factories often had nervous breakdowns.

Goddard later called it her favorite film. “Charlie could be difficult at times, but charming” and he gave her valued education and experience. Their collaboration would end due to a falling out after The Great Dictator.

A Bucket of Water and a Glass Matte: Craig Baron and Ben Burtt talk about visual and sound effects.

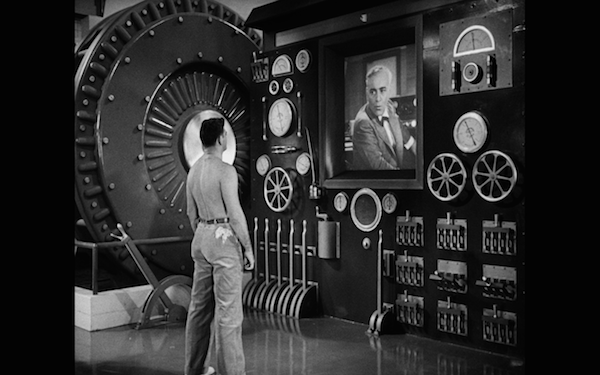

Chaplin isn’t thought of in terms of visual effects, but he used them effectively. He was a visual director because of his roots in silent film. He used techniques like miniatures, rear projection, glass shots, matte paintings, and many more. He built large sets, like he did with the factory. He used a lot of hanging miniatures, even during the factory sequence. They are smaller, yet they give the impression of appearing full-size, and they make the set look larger.

Sounds were used as needed for dramatic or comic effect, but no more. He preferred to use them only when necessary, such as the feeding machine and flatulence jokes.

They show the roller skating shot in detail. Chaplin used a glass matte painting shot. Camera shoots through a sheet of glass with a painting. The empty “cliff” is the painting. Chaplin was an exception skater, but was never in any danger.

Silent Traces: Modern Times: Visual essay with John Bengtson as he tours the locations that Chaplin used.

Chaplin began in Los Angeles, and many of the locations still exist today. He filmed factory scenes near gas storage tanks. The north of which was demolished in 1973. The landmark also appears in The Kid, Buster Keaton’s The Goat. The southern plant was smaller and used in the worker lineup scene.

Today the Chaplin studio in Hollywood is home to Jim Henson company, where Kermit pays tribute to Chaplin by dressing as the tramp.

David Raksin and the Score: 1992 interview with the composer for the film..